Parsi Culture and Sensibility in the Works of Playwrights Gieve Patel and Cyrus Mistry Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Introspection' in Nissim Ezekiel's Poetry:A Brief Note

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Theme of Alienation and ‘Introspection’ in Nissim Ezekiel’s Poetry:A brief Note M.Jayashree, Ph.D Scholar in English (P.T), E.M.G.Yadava College for Women, MADURAI – 625 014. Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract:This is an attempt to project Nissim Ezekiel as one of the major poets in Indian English literature in the current literary scenario, who is the one gifted with the power of influencing the theory and practice of several younger poets in addition to his own pioneering creative contribution to Indian poetry in English. It examines rather significantly how Ezekiel stands for simplicity, clarity, coherence, lucidity in art and literature and his poetic skill in treatment of various themes like loneliness, alienation and introspection, by bringing home the point that his poetry, acclaimed for its quality and vivacity, renders the contemporary themes of alienation, spiritual emptiness, isolation and fragmentation with humor, compassion and irony. Keywords: literary scenario, theory, practice, creative contribution, art, literature, alienation, introspection, compassion irony. Nissim Ezekiel, one of the major poets in Indian English literature, has expressed valuable ideas on literature and life in his letters, critical writings, poetic compositions and also interviews. He was in the vanguard of Indian poets writing in English. Much feted and acclaimed during his life time, Ezekiel was born on 6th Dec, 1924 in Bombay to Jewish (Bene-Israel) parents, who were deeply involved in education. He had his schooling at Antonio D’Souza High School and then studied at Wilson College, Bombay and later at Birbeck College, London (1948-52). -

Re-Construction of a Community: a Sustainable Attempt at Alternative Opportunities

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 5, May-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 1018 Re-construction of a Community: A sustainable attempt at alternative opportunities 1. WARLI- THE INDIGENOUS The 'Tribal' who are also known as Adivasis are India's original indigenous people. The indigenous people have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions and manifestations of their sciences and technologies as well as the right to intellectual property over those assets. The Warlis are one of the oldest pre-historic tribes amongst this platoon. While their ancient history is largely a point of conjecture, scholars generally believe that when Indo Aryans invaded what is now India; at least 3,000 years ago, they pushed these aborigines into more remote parts of the country, where they have largely remained to this very day. These people lived in isolated forestlands, far from urban centres. They belonged to their territories, which was the essence of their existence; the abode of their spirit and dead and the source of their science, technology, way of living, their religion and culture. This ushered the communities to remain far outside from India's mainstream and become self-governing entities which involuntarily fell outside the rigid Hindu caste system. Warlis (Adivasis) are today classified as 'Scheduled Tribes' by the Indian Constitution. Due to separation from the Hindu caste system, they are very different from 'Schedules castes' which belong to the caste system of India. They are unlike The Dalits (Untouchables), who are largely trapped in bonded servitude. -

Living Traditions Tribal and Folk Paintings of India

Figure 1.1 Madhubani painting, Bihar Source: CCRT Archives, New Delhi LIVING TRADITIONS Tribal and Folk Paintings of India RESO RAL UR U CE LT S U A C N D R O T R F A E I N R T I N N G E C lk aL—f z rd lzksr ,oa izf’k{k.k dsUn Centre for Cultural Resources and Training Ministry of Culture, Government of India New Delhi AL RESOUR UR CE LT S U A C N D R O T R F A E I N R T I N N G E C lk aL—f z rd lzksr ,oa izf’k{k.k dsUn Centre for Cultural Resources and Training Ministry of Culture, Government of India New Delhi Published 2017 by Director Centre for Cultural Resources and Training 15A, Sector 7, Dwarka, New Delhi 110075 INDIA Phone : +91 11 25309300 Fax : +91 11 25088637 Website : http://www.ccrtindia.gov.in Email : [email protected] © 2017 CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESOURCES AND TRAINING Front Cover: Pithora Painting (detail) by Rathwas of Gujarat Artist unknown Design, processed and printed at Archana Advertising Pvt. Ltd. www.archanapress.com All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Director, CCRT. Photo Credits Most of the photographs used in this publication are from CCRT Archives. We also thank National Museum, New Delhi; National Handicrafts & Handlooms Museum (Crafts Museum), New Delhi; North Zone Cultural Centre (NZCC), Patiala; South Central Zone Cultural Centre (SCZCC), Nagpur; Craft Revival Trust, New Delhi and Sanskriti Museum, New Delhi for lending valuable resources. -

GIEVE PATEL : LIFE, WORK and Hffloences

GIEVE PATEL : LIFE, WORK AND HffLOENCES GIEVE PATEL : LIFE AND WORK. Gieve Patel was born in Bombay in 1940 of Par see parents, and educated at St. Xavier's High School and Grant Medical College. "Never Did” in his Mirrored Mirroring is a vivid recollection of school life. For the poet, "Montessory/was monstrous; brightly coloured/pits and blocks were/tormenting." The second section of the poem deals with the humiliating experience in his school when he was only seven years old. The experience is dramatically presented by making ;use of presenjt tense. » At age seven he is tried before classmates, in his hands the offending book with a whole, unwieldy coconut gummed to centre page. • • • Boy and book are led through the school, a triumphal procession. "State and Fire", the symbol of torture in his poem "Say 9 Torture" (B), "are lit already/in his innards." After securing his medicai degrees, Patel started working as a General Practitioner in Bombay. Bis experience as a medical doctor in the public hospital, which left a lasting influence on his poetic career, is a subject of his famous poem "Public Hospital" (B). Here his personal experience transcends him; it becomes a metaphor, so that, what we find evoked, is the typical experience of any sensitive doctor who has to treat poor patients in India. * How soon I've acquired it all It would seem an age of hesitant gestures Awaited only this sententious month. Autocratic poise comes natural now; Voice sharp, glance impatient, A busy man's look of harried preoccupation- Not embarrassed to appear so. -

Performance of Scheduled Caste Members of Different Political

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION SUBMISSION OF MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT (FINAL REPORT) IN THE SUBJECT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE PROJECT PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY BY DR. BAL ANANT KAMBLE PRINCIPAL AND HEAD DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE RAYAT SHIKSHAN SANSTHA’S DADA PATIL MAHAVIDYALAYA, KARJAT -414402 DIST – AHMEDNAGAR ( MAHARASHTRA STATE ) Ref. : UGC file No. 5-243/2012(HRP) UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION SUBMISSION OF MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT (FINAL REPORT) IN THE SUBJECT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE PROJECT PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY BY DR. BAL ANANT KAMBLE PRINCIPAL AND HEAD DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE RAYAT SHIKSHAN SANSTHA’S DADA PATIL MAHAVIDYALAYA, KARJAT -414402 DIST – AHMEDNAGAR ( MAHARASHTRA STATE ) MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT Title : PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY CONTENTS Chapter No. Contents Page No. i. Introduction I 01 ii. Method of Study and Research Methodology Reserved Constituencies for Scheduled Caste in India and II 07 Delimitation of Constituencies III Scheduled Caste and the Politics of Maharashtra 19 Theoretical Debates About the Scheduled Caste MLAs IV 47 Performance Politics of Scheduled Castes in the Election of V 64 Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Performance Analysis of Scheduled Castes MLAs of VI 86 Different Political Parties of Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha VII Conclusions 146 References 160 List of Interviewed SC MLAs of Maharashtra Vidhan Annexure –I 165 Sabha. Annexure – II Questionnaire 170 Chapter I I – Introduction II – Method of Study and Research Methodology I – Introduction Chapter I is divided in to two parts: Part A and Part B. -

Wall Art, the Traditional Way

International Journal of Applied Home Science RESEARCH ARTICLE Volume 5 (4), April (2018) : 926-929 ISSN : 2394-1413 Received : 04.03.2018; Revised : 14.03.2018; Accepted : 26.03.2018 Wall art, the traditional way NITI ANAND Assistant Professor Department of Design (Fashion Design) BBK DAV College for Women, Amritsar (Punjab) India ABSTRACT Indian tribal art forms are like the expressions and feelings of people who belong to different states of Indian life sharing different languages, different cultural values and different rites and rituals. The folk and tribal arts are very ethnic and simple and yet colourful and vibrant enough to speak volumes about the countries rich heritage. Indian folk paintings have always have been famous for super creative and imaginative work. Some of the prominent paintings traditions under this have been Madhubani paintings of the Mithila region of Bihar, the Warli paintings of Maharashtra, Gond paintings of Madhya Pradesh, Kerala mural paintings, Pithora paintings Gujarat, Saora paintings Orissa. Key Words : Wall art, Indian tribal art, Pithora paintings, Saora paintings INTRODUCTION India has always been known as the land that portrayed cultural and traditional arts and craft. Every region in India has its own style and pattern of art, which is known as folk art. There are multiple modes through which folk and tribal art forms are represented in India. Due to diverse regional and tribal setup through the Indian Territory, we can find great difference in the depiction of feelings in these modes. The folk art can take up the form of pottery, paintings, metal work, paper art, weaving, jewellery, toy making. -

Mandatory Disclosure

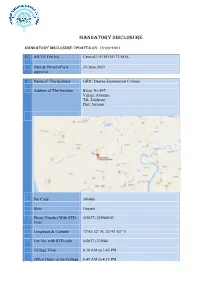

Mandatory disclosure Mandatory disclosure updated on: 13-09-2021 1. AICTE File No : Central/1-9319115173/EOA Date & Period of last : 25-June-2021 approval 2. Name of The Institute : GIDC Degree Engineering College Address of The Institute : Block No.997, Village Abrama, Tal. Jalalpore, Dist. Navsari Pin Code : 396406 State : Gujarat Phone Number With STD : (02637) 229040/41 Code Longitude & Latitude : 72o54’32” N; 20 o51’03” E Fax No. with STD code : (02637) 229041 College Time : 8.30 AM to 3.45 PM Office Hours at the College 8.45 AM to 4.15 PM Email ID : [email protected] Website : www.gdec.in College Fees : 25,000/- Per Year (W.E.F. from A.Y. 2020-21) Nearest Railway Station: Amalsad 05 KM from the campus Nearest Airport : Surat 55 KM from the campus Type of Institution : Public Private Partnership Category (1) of the : Non-Minority Institution Category (2) of the : Co-Ed Institution 3. Name of the Organization : GIDC Education Society running the Institution Type of the Organization : Society Address of the : Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation (GIDC). Organization Sector – 11, Udyog Bhavan, Block No. 3,4 & 5 Ghandhinagar -382017 Registered with: Under Society Registration Act 1960 Registration No. and Date : GUJ/1769/GANDHINAGAR dated 14.07.2010 Website of the : www.gidc.gov.in Organization 4. Name of the Affiliating : Gujarat Technological University, Chandkheda University Address of University : Nr. Campus of Vishwakarma Government Engineering College, Sabarmati –Koba Highway, Chankheda, Ahmadabad, Gujarat,Ph-07923267500 Website : www.gtu.ac.in Latest Affiliation Period : 2021-22 5. Name of Principal : Dr. -

Warli-E-Brochure.Pdf

Ojas is a Sanskrit word and may be inferred as the embodiment of the creative energy of the universe. Ojas is also described as the nectar of the third eye. Headed by Anubhav Nath, OJAS ART is a Delhi based art organization bringing forth the newest ideas in the contemporary art space. We endeavour to bring together artists and ideas supported by extensive research and thoughtful dialogues enabling creativity OJAS ART 1AQ, Near Qutab Minar and innovation. We are actively involved in Mehrauli, New Delhi 110030 +91 85100 44145 research, consultancy, and advising on building [email protected] collections. For the last decade we have been involved in promoting the contemporary Indian Indigenous Arts in a holistic manner involving an annual art award, exhibitions and publications. Amit Mahadev Dombhare Kishore Mashe Mayur & Tushar Vayeda Rajesh Vangad Sadashiv Mashe Shantaram Gorkhana Project Advisor Prof Neeru Misra The Art of the Warlis Prof. Neeru Misra manating in the laps of the foothills of The painters for years were able to base their lines drawn on an ochre red background. northern parts of the Sahyadri range of paintings on triangles, circles and squares, each ‘Irregular strokes of brush or sticks...are not the the Western Ghats, Warli style of painting having a simple but deep symbolism. Circle deformities, but distinctive traits of the art.’ Ehas a rich legacy of over a thousand years. represented the Sun and Moon, triangle was The paintings were not confined only to Mostly confined to the surrounding areas close symbolic of the conical mountain tops and celebrations of rituals and harvest seasons, but to Mumbai, Palghar, and Nasik, in Maharashtra; squares symbolized the enclosures or fields and the artists were also free to paint their walls Dang, Navsari and Surat in Gujarat and the even villages, huts or human dwellings. -

The 36Th Annual Conference on South Asia October 12

Center for South Asia University of Wisconsin-Madison The 36th Annual Conference on South Asia October 12 - 14, 2007 Madison Concourse Hotel 1 West Dayton Street Madison, WI 53703 [email protected] . http://southasiaconference.wisc.edu The 36th Annual Conference on South Asia Table of Contents October 12, 13, and 14, 2007 36th Annual Conference on South Asia Madison Concourse Hotel 1 West Dayton Street Madison, WI 53703 Sponsored by: Conference Information . .3 Center for South Asia Association Meetings . .5 University of Wisconsin-Madison Special Events . .6 203 Ingraham Hall Exhibitors . .6 1155 Observatory Drive Madison, WI 53706 Tel: 608-262-4884 Fax: 608-265-3062 Thursday, October 11 J. Mark Kenoyer, Director Sharon Dickson, Assistant Director Preconferences . .4 Program Committee University of Wisconsin-Madison Friday, October 12 Chair 8:30 - 10:15 am: Session 1 . .7 Aseema Sinha 10:30- 12:15 pm: Session 2 . .10 Department of Political Science 12:15 - 2:00 pm : Lunch and Roundtable . .12 2:15 - 4:00 pm : Session 3 . .13 Committee Members 4:15 - 6:00 pm : Session 4 . .16 6:00 - 7:00 pm : Reception and Social Hour . .18 Preeti Chopra 7:15 - 8:15 pm : All-conference Dinner . .19 Department of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Visual Culture 8:30 - 9:30 pm : Keynote Address . .19 Studies Donald Davis Department of Languages and Saturday, October 13 Cultures of Asia Christine Garlough 8:30 - 10:15 am: Session 5 . .20 Department of Communication Arts 10:30- 12:15 pm: Session 6 . .22 and Folklore Program 1:45 - 3:30 pm : Session 7 . -

No. Name Signatories Address 1 3D SERVICES DIGAMBAR M DEO 103 ,SAI DWAR CHS LTD, VISHAL NAGAR, AMBADI RD VASAI-W, 1, PIN - 401201 2 a AJAYKUAMAR AHIR MALDEV K

JANASEVA SAHAKARI BANK (BORIVLI) LTD.Name of Account holders whose accounts are inoperative more than ten years As on 30 Sep 2020 As per RBI Circular No. RBI/2014- 15/481/DCBR.BPD.(PCB/RCB)CIR.NO.18/13.01.000/2014-15 dated February 27 2015 No. Name Signatories Address 1 3D SERVICES DIGAMBAR M DEO 103 ,SAI DWAR CHS LTD, VISHAL NAGAR, AMBADI RD VASAI-W, 1, PIN - 401201 2 A AJAYKUAMAR AHIR MALDEV K. 30/SHYAM GALLI,PANKAJ MKT, , BORIVALI WEST MUMBAI, 0, PIN - 0 3 A BABU PLOT.NO-280/D-6,, GORAI-II, BORIVLI[W],MUMBAI, 0, PIN - 0 4 A S SERVICES MANOHAR SUJATA 3,DAS,BHAVAN,UNDERAI ROAD, MALAD, [W], MUMBAI, 6, PIN - 400064 5 A-TECH ENGINEERING RAUT ABHIJEET NARESH ,GALA NO.RX 153 2\2,, D.P RD,GANDHI NAGAR,, KANDIVALI(W) MUMBAI, 400067, PIN - 4000 6 A.B.C.D ANKUR GUPTA 101,EKTA ELEGANCE,, LINKING RD,OPP.YOGI NAGAR, BORIVLI (W) MUMB, 0, PIN - 0 7 A.B.C.D ARTIV GUPTA 101,EKTA ELEGANCE,, LINKING RD,OPP.YOGI NAGAR, BORIVLI (W) MUMB, 0, PIN - 0 8 A.B.C.D ABHINAV GUPTA 101,EKTA ELEGANCE,, LINKING RD,OPP.YOGI NAGAR, BORIVLI (W) MUMB, 0, PIN - 0 9 A.V.BHANDARKAR FAMILY TRU , , , 0, PIN - 10 A.V.BHANDARKAR FAMILY TRU , , , 0, PIN - 11 AADAV SHAHUBAI BHAURAO ,JIJAMATA CHAWL, HANUMAN NAGAR, AKURLI ROAD KANDIVALI (E), 2, PIN - 400101 12 AADAWALE KANTABAI SANTARA 38 ,AAKURLI SANGAM R NO D-1, R S C 4, MHADA KANDIVLI EAST, 2, PIN - 400101 13 AAGRA PRATIBHA PARSHURAM N0 87,MAHAMYA CHAWL ,GAUT, KRANTI NAGAR,KANDIVALI [E, MUMBAI KANDIVALI(E), 2, 14 AAHIR P BHIKHABHAI SHOP NO. -

THE BOMBAY REORGANISATION BILL, I960

C.B. II No. 103 LOK SABHA THE BOMBAY REORGANISATION BILL, i960 Report of the Joint C ommittee Presented on the 14th April, i960 VMM! LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April, 1960% Price : Rs. I.SO JoiatAialfrt SnaaiUflg Stuart priim ud to tho fak jaoh^ during thm 3fl thy 11th »flfl ISfck^aaalw&g o f fltwBti t o t &*' a t i * £ u i 9 - aontatian *oloct Coaaittoo on tho Proforonoo 6 . 1 2 . 3 0 6 0 Bharoo( Bofulation o f Blvidando) Billy I 9 6 0 . oa Um Mlfii Land 8.2*3960. Bolding a( Colling) Bill, ]MI. feint CoHitt«i on tho frlfir*tarvra Land -do- Bovonuo and Land hofom# BillyB; * a » . Joint Coaaictoo on tho Manipur Land -do- Boroaao and Land ftafOma Billy 1BBB. Joint Coaalttoo on tho Local praoti- 2B.3.&60 tlonor* a 1 1 1 , lBfii. Joint Goaaiti.fi on th« Boa bay 14.4.1960 Kao realisation Billy IB 60. Joint Coaalttce oc th# Cooptolas 30.8.3960 tAaccdxent) Billy 1B6B a i th. Svldanoo, Joint Coaalttoo on tho Motor 6.12. I960 7 ran apart Koxkora Billy I960 with BTidf^O O . CONTENTS Paob 1. Composition of the Joint Committee . yji) 2. Report of the Joint Committee . ....................................... (y) 3. Minutes of Distent .... ....................................... c » 4. Bill as reported by the Joint Committee .... 1 A p pe n d ix I— Motion in the Lok Sabha for reference of the Bill to Joint Committee . 65 APPENDIX II— Motion in the Rajya Sabha . .... 67 Ap pe n d ix I II— Statement of memoranda/representations received by the Joint Committee 66 Ap p e n d ix IV — Minutes of the Sittings of the Joint C o m m itte e..................................... -

Higher Prevalence of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) Deficiency in Tribal Population Against Urban Population: a Signal to Natural Selection

Biomedical Research 2017; 28 (1): ISSN 0970-938X www.biomedres.info Higher prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency in tribal population against urban population: a signal to natural selection. Ishani Shah1, Jummanah Jarullah2, Soad Al Jaouni2, Mohammad Sarwar Jamal2, Bushra Jarullah1* 1Department of Biotechnology, KadiSarva Vishwavidhyalaya, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 2King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Abstract Background: Human genetic variation is interlinked to genetic drift and gene flow. Interplay amongst these leads to evolution in natural populations. Studies suggest that Glucose-6- Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD)-deficient alleles show some signatures of selection. Deficiency in G6PD is the most common enzyme deficiency of human erythrocyte which affects over 400 million people worldwide. There is no comprehensive information available about the prevalence of this disease across the entire map of Gujarat, India. Methods: Cross-section retrospective study was conducted to determine prevalence of G6PD deficiency in population of Gujarat. 3467 samples from different hospitals throughout the state of Gujarat from September 2014 to September 2015. The G6PD activity was measured quantitatively by spectroscopic absorbance at 340 nm in kinetic mode. Results: The drastic variation in the prevalence amongst the tribal and urban population was observed. Frequency varied from 11.18% in tribal populations to as low as 1.2% in the urban population. Urban areas such as Kutch, Bhuj, Lunawada and Kapadwanj showing relatively high prevalence have been known to be inhabited by tribal population. Conclusions: Heterozygosity levels, linkage disequilibrium patterns and frequencies of alleles segregating in a population play a vital role in the prevalence of any genetic deficiency.