Tobacco Industry Is an Important Example

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

"I Always Thought They Were All Pure Tobacco'': American

“I always thought they were all pure tobacco”: American smokers’ perceptions of “natural” cigarettes and tobacco industry advertising strategies Patricia A. McDaniel* Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, School of Nursing University of California, San Francisco 3333 California Street, Suite 455 San Francisco, CA 94118 USA work: (415) 514-9342 fax: (415) 476-6552 [email protected] Ruth E. Malone Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, School of Nursing University of California, San Francisco, USA *Corresponding author The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Tobacco Control editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://tc.bmj.com/misc/ifora/licence.pdf). keywords: natural cigarettes, additive-free cigarettes, tobacco industry market research, cigarette descriptors Word count: 223 abstract; 6009 text 1 table, 3 figures 1 ABSTRACT Objective: To examine how the U.S. tobacco industry markets cigarettes as “natural” and American smokers’ views of the “naturalness” (or unnaturalness) of cigarettes. Methods: We reviewed internal tobacco industry documents, the Pollay 20th Century Tobacco Ad Collection, and newspaper sources, categorized themes and strategies, and summarized findings. Results: Cigarette advertisements have used the term “natural” since at least 1910, but it was not until the 1950s that “natural” referred to a core element of brand identity, used to describe specific product attributes (filter, menthol, tobacco leaf). -

Arrest Report - 2019

Arrest Report - 2019 Arrest:19TEW-41-A-AR Date:1/1/2019 Last Name: CORREA First Name:YANELA Age: 18 Address:156 CYPRESS ST City:MANCHESTER State: NH Offense COCAINE, TRAFFICKING IN, 36 GRAMS OR MORE, LESS THAN 100 GRAMS Arrest:19TEW-41-AR Date:1/1/2019 Last Name: MENDOZA First Name:ELVIN Age: 22 Address:9 BYRON AVE City:LAWRENCE State: MA Offense COCAINE, TRAFFICKING IN, 36 GRAMS OR MORE, LESS THAN 100 GRAMS WARRANT - 1818CR003461 - TRAFFICKING IN 100 GRMS HEROIN WARRANT-DOCKET#1818CR006396 - OP MV W/ REVOKED LICENSE Arrest:19TEW-294-AR Date:1/2/2019 Last Name: KING First Name:TAMMY Age: 37 Address:181 LOUDON RD City:CONCORD State: NH Offense ASSAULT W/DANGEROUS WEAPON/ TO WIT CLEANING BOTTLE VANDALIZE PROPERTY c266 §126A DISGUISE TO OBSTRUCT JUSTICE WARRANT -LARCENY OVER 1200.00 266/30/B WARRANT - LARCENY OVER 1200.00 - 266/30/A WARRANT - LARCENY OVER 1200.00 BY SINGLE SCHEME - 266/30/B WARRANT - SHOPLIFTING $250+ BY ASPORTATION - 266/30A/S THREAT TO COMMIT CRIME - ASSAULT & BATTERY Arrest:19TEW-337-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: PUNTONI First Name:CORY Age: 27 Address:10 LOCKE ST City:HAVERHILL State: MA Offense WARRANT- DOCKET#1838CR002437-ORDINANCE VIOLATION Arrest:19TEW-470-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: GUTHRIE First Name:CHRISTOPHER Age: 31 Address:108 CHAPEL ST City:LOWELL State: MA Offense Page 1 of 10 WARRANT DOCKET #1711CR001501 C275 S2 THREATENING TO COMMIT CRIME WARRANT DOCKET #1811CR004055 90-23 LICENSE SUSPENDED Arrest:19TEW-485-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: DYESS First Name:CHRISTOPHER Age: 35 Address:133 SHAWSHEEN ST City:TEWKSBURY -

Trustees Order·. Desegregation

Columnist Reviews ACC Baseball Teams Honors Program, d. PCJ&o Use 'Speed-Up' Rules LaJfbact ·Suggests Changes ~ of the On Experimental Basis !k. The Page 2 lb ldsboro, .. / Page 5 ial ol 71 .... / ·' ~veniDg. win the tdefeDse· I VOLUME XLVIJ Wake FDrest College, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, MDnday, April 30, 1962 * * NUMBER 26 . E!gge's· * actor ol TRUSTEES ORDER·. DESEGREGATION Kl. raiD • No Formal· Action Taken On Controversial Novel Forest Student Body Chooses Leaders For Coming Year uk:e ~urman SPCops 19; 1emson UPWins13 Racial Barriers Lowered Completely outh By RAY SOUTHARD "This committee recommends to Steve Glass, Greensboro junior, Associate Editor ments or housing matters were not Immediate unofficial reaction to the Trustees that we carry out the touched on at the meeting. Pre- the adoption of the resolution was >uke was elected April 17 as president The trustees of Wake Forest Col will expressed by the Baptist State of the student body. sumably these will be left entirely 1 favorable. The move has been ex lege Friday adopted a resolution .C<>nvention las~ November and to the administration of the Col· pected and did not come as a sur calling for desegregation of the un Glass, United Party candidate, allow qualified students to enter lege. prise. A few students and adminis- uk:e, defeated Students' Party candidate dergraduate school. Wake F<Y.rest C<>llege regardless of L. Y. Ballentine of Raleigh is tration officials questioned before Jack Hamrick· of Shelby by 163 By a vote of 17-9, with four ab race." stentions, the trustees adopted a Chairman of the Race Relations press deadlines indicated pleasure votes. -

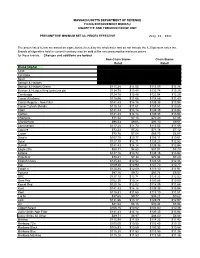

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Wake Forest University Magazine

orest February 1991 Wake Forest University Magazine Allen Mandelbaum: The 'Dancing Master' orest Wake Forest University Magazine Volume 37, Number 3 February 1991 Editor Features 2 Jeanne P. Whitman The Minds of the South Symposium 2 • Associate Editor WJ. Cash's Mind 9 • Is the Racist South Cherin C. Poovey Staging a Comeback? 10 • Staff Writer Profile: Allen Bernie Quigley Mandelbaum 12 Classnotes Editor Adele LaBrecque Typography Rachel Lowry Printing Fisher-Harrison Corp. University Departments 17 Photography Women's Studies: A Look Back 17 Front cover: Kenan Professor of Humanities Allen Mandelbaum, • Sociology: Educating the Work by Susan Mullally Clark. Force 18 • Medicine: Fighting for the Charlie Buchanan: 3 (top); 4, Lives of Infants 20 • Law: Marion 5, 6 (top); 7 (top); 8, 29; Benfield Joins 21 Susan Mullally Clark: 3 Faculty (center, bottom); 6 (center, bottom); 7 (bottom); 11, 13, 15 , 16 , 19, 21, 22, 23 , 24, 26 , 28 , 30, 35; Jack Gold, 34; Campus Chronicle 22 Scott Manin, 27; Courtesy of Founders' Day: Grant Announced, Charles Elkins Jr., 9; Bowman Gray School of Medicine, 20. Faculty Honored 22 • Edward Rey nolds Returns 24 • New Trustees 25 • International Executive Program 25 • WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY Preparing for a Semester in Japan 26 MAGAZINE (USPS 664-520, ISSN 0279- 3946) is published five rimes a • A Fourth Rhodes Scholar 27 year in September, November, February, April and July by Wake Forest Universi ty. Second class postage paid ar Winsron-Salem, NC, and additional Alumni Report 29 mailing offices. Please send letters ro Trustees Pledge to Campaign 29 the ecliror and alumni news to WAKE • Pughs FOREST UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE, Name Auditorium 29 • Benson Gift to 7205 Reynolda Station. -

Case Study Industry: Tobacco

CASE STUDY INDUSTRY: TOBACCO CUSTOMER: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company LOCATION: Winston Salem, North Carolina BACKGROUND: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company is the second-largest tobacco company in the United States, offering products in all segments of the market and makes many of the nation’s best-selling cigarette brands, including: Camel, Pall Mall, Kool, Winston, Salem, Doral, and VUSE brand E-cigarette. SCOPE OF WORK: Armstrong International is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the utilities systems at the Tobaccoville and Whitaker Park Boiler and Process Services plants including all associated equipment to provide quality steam, condensate, chill water, compressed air, and water treatment to meet ISO, FDA, and process requirements of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company manufacturing facilities. Armstrong provides one site manager, two operation and maintenance managers as well as 35 operation and maintenance support employees, which includes 18 utility plant operators, one water treatment specialist, four operations and maintenance lead technicians, 11 HVAC and instrumentation technicians, and four mechanical maintenance technicians to furnish continuous plant staffing. BENEFITS: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company now has on-site utility expertise motivated to continually reduce cost and focus on utility system reliability at two separate manufacturing locations. They also have access to all of Armstrong’s extensive utility/energy engineering resources including the following: • Annual engineering audits • Identification/development -

NVWA Nr. Merk/Type Nicotine (Mg/Sig) NFDPM (Teer)

NVWA nr. Merk/type Nicotine (mg/sig) NFDPM (teer) (mg/sig) CO (mg/sig) 89537347 Lexington 1,06 12,1 7,6 89398436 Camel Original 0,92 11,7 8,9 89398339 Lucky Strike Original Red 0,88 11,4 11,6 89398223 JPS Red 0,87 11,1 10,9 89399459 Bastos Filter 1,04 10,9 10,1 89399483 Belinda Super Kings 0,86 10,8 11,8 89398347 Mantano 0,83 10,8 7,3 89398274 Gauloises Brunes 0,74 10,7 10,1 89398967 Winston Classic 0,94 10,6 11,4 89399394 Titaan Red 0,75 10,5 11,1 89399572 Gauloises 0,88 10,5 10,6 89399408 Elixyr Groen 0,85 10,4 10,9 89398266 Gauloises Blondes Blue 0,77 10,4 9,8 89398886 Lucky Strike Red Additive Free 0,85 10,3 10,4 89537266 Dunhill International 0,94 10,3 9,9 89398932 Superkings Original Black 0,92 10,1 10,1 89537231 Mark 1 New Red 0,78 10 11,2 89399467 Benson & Hedges Gold 0,9 10 10,9 89398118 Peter Stuyvesant Red 0,82 10 10,9 89398428 L & M Red Label 0,78 10 10,5 89398959 Lambert & Butler Original Silver 0,91 10 10,3 89399645 Gladstone Classic 0,77 10 10,3 89398851 Lucky Strike Ice Gold 0,75 9,9 11,5 89537223 Mark 1 Green 0,68 9,8 11,2 89393671 Pall Mall Red 0,84 9,8 10,8 89399653 Chesterfield Red 0,75 9,8 10 89398371 Lucky strike Gold 0,76 9,7 11,1 89399599 Marlboro Gold 0,78 9,6 10,3 89398193 Davidoff Classic 0,88 9,6 10,1 89399637 Marlboro Red 100 0,79 9,6 9 89398878 Lucky Strike Ice 0,71 9,5 10,9 89398045 Pall Mall Red 0,81 9,5 10,5 89398355 Dunhill Master Blend Red 0,82 9,5 9,8 89399475 JPS Red 0,81 9,5 9,6 89398029 Marlboro Red 0,79 9,5 9 89537355 Elixyr Red 0,79 9,4 9,8 89398037 Marlboro Menthol 0,72 9,3 10,3 89399505 Marlboro -

Local & Imported Cigarettes

LOCAL & IMPORTED CIGARETTES REGIE CEDARS 100 MM CEDARS PLUS FF KS BOX CEDARS PLUS SILVER KS BOX CEDARS PLUS FF SKS SOF CEDARS PLUS SILVER SKS SOF MAESTRO FULL FLAVOR SKS SOFT MAESTRO VIOLET SKS SOFT PHILIP MORRIS EXPORTS Sarl MARLBORO K.S BOX MARLBORO FILTER + K.S BOX MARLBORO FINE TOUCH KS BOX MARLBORO FINE TOUCH XL 5mg MARLBORO MEDIUM FF KS BOX MARLBORO K.S SOF MARLBORO GOLD K.S BOX MARLBORO GOLD K.S SOF MARLBORO SILVER KS BOX MARLBORO GOLD S.K.S SOF MERIT SKS SOF MERIT 100'S BOX R.C. CHESTERFIELD S K.S SOF BOND S K.S SOF BOND BLUE S K.S SOF BOND STREET BLUE SUPER SLIMS J T International S.A. WINSTON K.S SOF WINSTON K.S BOX WINSTON S.S. L. K.S BOX WINSTON S.S. U.L. K.S BOX WINSTON S.S. MENT. K.S BOX WINSTON XS RED KS BOX WINSTON XS BLUE KS BOX WINSTON BLUE KS SOF WINSTON BLUE S.K.S BOX WINSTON BLUE K.S BOX WINSTON SILVER K.S BOX GLAMOUR PINKS SSL GLAMOUR MENTHOL SSL WINCHESTER KS BOX WINCHESTER L KS BOX WINCHESTER BLUE JUMBO KS CAMEL FF BOX (Yellow) CAMEL BLUE BOX WINCHESTER LIGHT SKS SOFT B.A.T (U.K.and EXPORT) limited VICEROY K.S SOF VICEROY LIGHTS BLUE VICEROY ULTRA LIGHTS SILVER VICEROY BLUE SUPER SLIMS LUCKY K.S SOF KENT PREMIUM LIGHT SKS BOX KENT BLUE KENT WHITE KENT SILVER KENT NANO BLACK KENT I SWITCH 8 MG KENT SPARK CORE BLUE KS KENT SPARK CORE SILVER KS ROTHMANS FIN K.S BOX DUNHILL LIGHT ROYALITY IMPERIAL TOBACCO IN GAULOISES BLONDES RED KS GAULOISES BLONDES BLUE KS GAULOISES BLONDES YELLOW KS ROYALE RED SKS BY WEST ROYALE BLUE SKS BY WEST BRILLIANT KS PRINTED TT Altadis Middle East FZCO GITANE INDIGO K.S BOX GITANE BLUED K.S BOX GITANE SHELL & SLIDE LIGHTS GITANE BLUE SUPER SLIM GAULOISE BLEU K.S BOX GAULOISES QUEEN SIZE RC UL GAULOISE RED K.S BOX GAULOISE YELLOW K.S BOX BRILLIANT WEST SLIM L .KS BOX DAVIDOFF GOLD BOX DAVIDOFF CLASSIC BOX DAVIDOFF GOLD SLIM BOX DAVIDOFF BLUE K.S BOX DAVIDOFF ONE VON EICKEN ALLURE WHITE SUPER SLIMS ALLURE BLACK SUPER SLIMS ALLURE MENTHOL SUPER SLIMS SOCIETE AKIKI S.A.R.L. -

Read the Fall 2018 Newsletter

FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NEWS FROM FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NONPROFIT ORG. 412 South Cherry Street U.S. POSTAGE Richmond, Virginia 23220 PAID PERMIT NO. 671 23232 A Gateway Into History WWW.HOLLYWOODCEMETERY.ORG FALL 2018 • VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 Finding Emily Arents A Chance Meeting Leads a California Woman to “Miss Grace” lthough she grew up hearing stories about her was Rev. Barbara Ambrose, a vocational deacon at St. relative Lewis Ginter (1824-1897), the tobacco Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, for which magnateA and real estate developer, Emily Arents knew Grace had funded the construction. little about Grace, his niece, and her great-great aunt. A chance conversation with a friend in January inspired “I am such a fan of Grace,” says Ambrose, who had also her to take a long-planned trip to Richmond with her written an article about the prominent Richmonder for a daughter, Leilani Cochran, to learn more about her Friends of Hollywood Cemetery newsletter. Working with mysterious family member. Emily, she helped coordinate a Grace-focused trip around Richmond. “It was fun on our end because I realized “All of this was Emily had no idea what she would be walking into, and prompted by a friend people were just really, really excited about this whole of mine at church,” prospect.” says Arents, speaking by phone from her The trip begins home in Arcata, California. “My Emily Arents grew up outside New York City. She friend was doing remembers passing through Richmond on her way to some research last boarding school at Chatham Hall but had never visited. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Blue 100 Box 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Blue King Box 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

JTI Response to the UK Department of Health's Consultation on the Future

Response to the UK Department of Health’s Consultation on the Future of Tobacco Control 5 September 2008 Japan Tobacco International is a subsidiary of Japan Tobacco Inc., the world’s third largest global tobacco company. It produces three of the top five worldwide cigarette brands: Winston, Mild Seven and Camel. Other international brands include Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Sobranie of London, Glamour and LD. With headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, and net sales of USD 8 billion in the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007, Japan Tobacco International has more than 22,000 employees and operations in 120 countries. Since April 2007, Gallaher Limited (“Gallaher”), the UK-based tobacco products manufacturer, has also formed part of the Japan Tobacco Group. In this response to the FTC Document, we use the term “JTI” to refer collectively to Japan Tobacco International and Gallaher. JTI, which has its UK headquarters in Weybridge, Surrey, has a long-standing, significant presence in the UK market. Its UK cigarette brand portfolio includes Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Camel, Mayfair, Sovereign and More, as well as a number of other tobacco products including cigars (such as Hamlet), roll-your-own tobacco and pipe tobacco. JTI manufactures product for the UK market at sites in the UK (in Northern Ireland and Cardiff) and outside it (for example, in Germany). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY JTI agrees with the key policy rationale underlying the Department of Health’s Consultation on the Future of Tobacco Control (the FTC Document): “children and young people” should not smoke, and should not be able to buy tobacco products.