Understanding Attitudes Towards Music Leisure Activity and the Constraints Faced by the Elderly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin FEBRUARY 2013

ISSUE 51- 52 Bulletin FEBRUARY 2013 Kaohsiung Exhibition & Convention Center BANGKOK BEIJING HONG KONG SHANGHAI SINGAPORE TAIWAN CONTENTS AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS 01 MAA Bulletin Issue 51- 52 February 2013 BIM PROJECT CASE STUDY 12 MAA TAIPEI NEW OFFICE 13 PROJECTS 1ST MAY 2011 TO 29TH 14 FEBRUARY 2012 Founded in 1975, MAA is a leading engineering and consulting service provider in the East and Southeast Asian region with a broad range PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES 22 of focus areas including infrastructure, land resources, environment, - PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES buildings, and information technology. - PROFESSIONAL AWARDS/HONORS - SEMINARS AND CONFERENCE - TECHNICAL PUBLICATIONS To meet the global needs of both public and private clients, MAA has developed sustainable engineering solutions - ranging from PERSONNEL PROFILES 26 conceptual planning, general consultancy, engineering design to project management. MAA employs 1000 professional individuals with offices in the Greater China Region (Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Taiwan), Mekong Region (Bangkok), and Southeast Asian Region (Singapore), creating a strong professional network in East/Southeast Asia. MAA’s business philosophy is to provide professional services that will become an asset to our clients with long lasting benefits in this rapidly changing social-economic environment. ASSET represents five key components that underlineMAA ’s principles of professional services: Advanced Technology project Safety client’s Satisfaction ISO 9001 and LAB CERTIFICATIONS Economical Solution Timely -

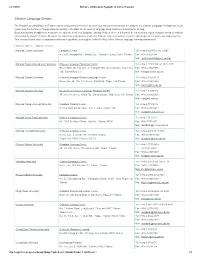

Chinese Language Centers

24/1/2015 Ministry of Education Republic of China (Taiwan) Chinese Language Centers The Republic of China(ROC) on Taiwan has for many years been home to numerous institutions devoted to the study of the Chinese Language. Perhaps this is one reason why the number of foreign students coming to the ROC for all levels of language study has been increasing for so long. Students find that in addition to being able to enjoy the benifits of language training facilities, there is a much to be learned from experiencing the blend of tradition and modernity found in Taiwan. Students can simultaneously observe traditional Chinese culture as well as enjoy the advantages of a modern, developed society. This, combined with ease of association with native speakers, is enough to make the ROC a fine Chinese language learning environment. Listing of Chinese Language Centers National Central University Language Center Tel: +88634227151 ext. 33807 No. 300, Jhongda Rd. , Jhongli City , Taoyuan County 32001, Taiwan Fax: +88634255384 Mail: mailto:[email protected] National Taipei University of Education Chinese Language Education Center Tel: +886227321104 ext.2025, 3331 Room 700C, No.134, Sec. 2, Heping E. Rd., Daan District, Taipei City Fax: +886227325950 106, Taiwan(R.O.C.) Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan University Chinese Language Division Language Center Tel: +886233663417 Room 222, 2F , No. 170, Sec.2, XinHai Rd, Taipei, 106,Taiwan Fax: +886283695042 Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan University International Chinese Language Program (ICLP) Tel: +886223639123 4F., No.170, Sec.2, Xinhai Rd., Daan District, Taipei City 106, Taiwan Fax: +886223626926 Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan Normal University Mandarin Training Center Tel: +886277345130 No.162 Hoping East Road , Sec.1 Taipei, Taiwan 106 Fax: +886223418431 Mail: [email protected] National Chiao Tung University Chinese Language Center Tel: +88635131231 No. -

Taiwan--Taipei--Retail-Q4-2019-Eng.Pdf

M A R K E T B E AT TAIPEI Retail Q4 2019 12-Mo. Clothing Brand NET Expands in Zhongxiao Retail Hub Forecast Vacancy rates at Ximen and Taipei Main Station climbed in Q4 while remaining stable in Zhongshan/Nanjing and dipping in Zhongxiao. Rental levels grew slightly in Ximen, while dropping at Taipei Main Station and at the Zhongxiao retail hub. In Zhongxiao the exit of several retailers had 13,400 caused a rise in the vacancy rate. In response, landlords offered rent reductions, prompting clothing and catering sectors to expand, including AVERAGE RENT (NTD/PING/MO) fashion brand NET taking the former storefront of Yunfulou restaurant. Consequently the Zhongxiao vacancy rate edged down 4 percentage points q-o-q to 7.7% in Q4. The FAVtory food court in Zhongshan/Nanjing closed in Q3. The storefront was leased to Poya in Q4, marking the first time 0% the chain has entered the Zhongshan/Nanjing retail hub. The completion of the MRT Zhongshan Station Xianxing Park helped boost convenient RENTAL GROWTH RATE(QOQ) pedestrian access and the park is expected to become an attraction in Zhongshan/Nanjing. Combination of Cosmopolitan Style and Leisure a Significant Trend 4.5% Tsutaya Bookstore opened at Citylink Nangang in December, with the 500-ping store incorporating a parent-child reading area in line with Citylink’s VACANCY RATE family-friendly environment. In response to the shift towards smaller families, growing numbers of malls are adopting a combination of Source: Cushman & Wakefield Research (Figures are cosmopolitan style and leisure in their planning. The concept was demonstrated at the 13,000-ping Far Eastern Department Store at Xinyi block growth rates as of Q4 2019.) A13, introducing Taiwan’s first officially authorized Lego specialty store, combining a Lego experience area and sales floor. -

Website : the Bank Website

Website : http://newmaps.twse.com.tw The Bank Website : http://www.landbank.com.tw Time of Publication : July 2018 Spokesman Name: He,Ying-Ming Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02)2348-3366 E-Mail: [email protected] First Substitute Spokesman Name: Chu,Yu-Feng Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02) 2348-3686 E-Mail: [email protected] Second Substitute Spokesman Name: Huang,Cheng-Ching Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02) 2348-3555 E-Mail: [email protected] Address &Tel of the bank’s head office and Branches(please refer to’’ Directory of Head Office and Branches’’) Credit rating agencies Name: Moody’s Investors Service Address: 24/F One Pacific Place 88 Queensway Admiralty, Hong Kong. Tel: (852)3758-1330 Fax: (852)3758-1631 Web Site: http://www.moodys.com Name: Standard & Poor’s Corp. Address: Unit 6901, level 69, International Commerce Centre 1 Austin Road West Kowloon, Hong Kong Tel: (852)2841-1030 Fax: (852)2537-6005 Web Site: http://www.standardandpoors.com Name: Taiwan Ratings Corporation Address: 49F., No7, Sec.5, Xinyi Rd., Xinyi Dist., Taipei City 11049, Taiwan (R.O.C) Tel: (886)2-8722-5800 Fax: (886)2-8722-5879 Web Site: http://www.taiwanratings.com Stock transfer agency Name: Secretariat land bank of Taiwan Co., Ltd. Address: 3F, No.53, Huaining St. Zhongzheng Dist., Taipei City 10046, Taiwan(R,O,C) Tel: (886)2-2348-3456 Fax: (886)2-2375-7023 Web Site: http://www.landbank.com.tw Certified Publick Accountants of financial statements for the past year Name of attesting CPAs: Gau,Wey-Chuan, Mei,Ynan-Chen Name of Accounting Firm: KPMG Addres: 68F., No.7, Sec.5 ,Xinyi Rd., Xinyi Dist., Taipei City 11049, Taiwan (R.O.C) Tel: (886)2-8101-6666 Fax: (886)2-8101-6667 Web Site: http://www.kpmg.com.tw The Bank’s Website: http://www.landbank.com.tw Website: http://newmaps.twse.com.tw The Bank Website: http://www.landbank.com.tw Time of Publication: July 2018 Land Bank of Taiwan Annual Report 2017 Publisher: Land Bank of Taiwan Co., Ltd. -

Chapter 7. Special Notes Affiliates 1

Chapter 7. Special Notes Affiliates 1. Investment holding structure As of December 31, 2012 Taiwan Mobile 5.86% Co., Ltd. 3.5% 12% 100% 100% Wealth Media Taiwan Cellular Technology Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. 50.64% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Taiwan Fubon Multimedia Win TV Global Wealth Global Forest Taiwan Digital Media Media TFN Media TCC Investment TWM Holding Teleservices & Taiwan Fixed Technology Co., Broadcasting Communications Technology Technology Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co. Ltd. Technologies Co., Network Co., Ltd. Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. Ltd. 6.83% 0.76% 100% 100% 100% 100% 92.38% 99.22% 100% 29.53%(Note) 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% TCCI Fu Sheng Fuli Property Fuli Life Asian Crown Globalview Phoenix Mangrove Yeong Jia Taiwan Kuro TWM Taiwan Super TT&T TFN Union Insurance Insurance Union Cable Investment and TFN HK Travel Service International Cable TV Co., Cable TV Co., Cable TV Co., Leh Cable TV Times Co., Communications Basketball Holdings Investment Co., Ltd. Agent Co., Agent Co., TV Co., Ltd. Development Ltd. Ltd. Ltd. Co., Ltd. Ltd. Ltd. Ltd. Co., Ltd. Ltd. Co., Ltd. (Beijing) Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. Co., Ltd. 100% 100% 100% Xiamen Taifu ezPeer Teleservices & Multimedia Technologies Fortune Ltd. Co., Ltd. Kingdom Corp. 100% Hong Kong Fubon Multimedia Technology Co., Ltd. 80% Fubon Gehua (Beijing) Enterprise Ltd. Note: 70.47% of shares are held under trustee accounts. 107 2. Affiliates’ profile Unit: NT$ (unless otherwise stated) Name Date of Address Paid-in capital Main business incorporation Taiwan Cellular Co., 13F-1, No. -

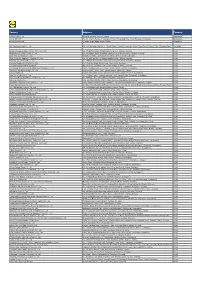

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Predictors of Hospital Staff Willingness to Provide Smoking Cessation Referral

Preventive Medicine Reports 3 (2016) 229–233 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Preventive Medicine Reports journal homepage: http://ees.elsevier.com/pmedr Improving smoking cessation outcomes in secondary care: Predictors of hospital staff willingness to provide smoking cessation referral Yin-Yu Chang a,Shu-ManYub,Yun-JuLaib,Ping-LunWub,c, Kuo-Chin Huang c,d, Hsien-Liang Huang b,c,e,⁎ a Department of Family Medicine, Taiwan Adventist Hospital, 424 Sec. 2 Bade Road, Songshan District, Taipei City 105, Taiwan b Department of Family Medicine, Cardinal Tien Hospital, 362 Zhongzheng Road, Xindian District, New Taipei City 231, Taiwan c Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, 1 Changde Street, Zhongzheng District, Taipei City 100, Taiwan d Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Science, China Medical University, 91 Hsueh-Shih Road, Taichung 404, Taiwan e School of Medicine, Fu-Jen Catholic University, 510 Zhongzheng Road, Xinzhuang District, New Taipei City 242, Taiwan article info abstract Article history: Since implementation of the New Smoking Cessation Policy in Taiwan, more patients are attending smoking Received 16 August 2015 cessation clinics. Many of these patients were referred by hospital staff. Thus, factors which influence the hospital Received in revised form 1 February 2016 staff's willingness to refer are important. In this study, we aim to understand the relation between smoking Accepted 29 February 2016 cessation knowledge and willingness for referral. Available online 4 March 2016 A cross-sectional study using a questionnaire was conducted with staff of a community hospital during the year 2012–2013. Willingness to provide smoking cessation referral and relevant correlated variables including demo- Keywords: Smoking cessation graphic data, knowledge of basic cigarette harm, and knowledge of resources and methods regarding smoking Hospital personnel cessation were measured. -

APHERP Senior Seminar Hong Kong

Emergent Scholar Seminar in Malaysia “Changing Dynamics of Asia Pacific Higher Education” National Higher Education Research Institute (IPPTN) Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia October 9 – 11, 2014 Dr. Azlan Amran Ms. Frederique Bouilheres Associate Research Fellow, Associate Professor Lecturer National Higher Education Research Institute (NaHERI) RMIT University Vietnam Block C, Level 2, sains@usm Office 2.3.40 No. 10, Persiaran Bukit Jambul 702 Nguyen Van Linh, Q7 11900 Bayan Lepas, Penang, Malaysia T.P. Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam [email protected]; [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Stephanie Kim Prof. Siu-yau Lee Postdoctoral Scholar, Center for Korean Studies Assistant Professor, Department of Asian & Policy Studies University of California, Berkeley The Hong Kong Institute of Education 1995 University Avenue Room 32 2/F Block 2, 10 Lo Ping Road, Tai Po Berkeley, California 94704 New Territories, Hong Kong, SAR [email protected] [email protected] Ms. Chiara Logli Dr. Asmak Abdul Rahman Lecturer; Ph.D. Candidate Syariah and Economics Department University of Hawaii at Mānoa, College of Education University of Malaya 1711 East-West Road, Mailbox 602 Faculty of Economics and Administration Honolulu, Hawaii 96848 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Munir Shuib Dr. Albert Wei-min Tan Associate Professor, Deputy Director Associate Professor, Department of Communication National Higher Education Research Institute (NaHERI) Fu Jen Catholic University Block C, Level 2, sains@usm No. 510 Zhongzheng Road No. 10, Persiaran Bukit Jambul Xinzhuang District, New Taipei City, 24205 Taiwan 11900 Bayan Lepas, Penang, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected] Ms. -

Farglory Land Development Co., Ltd. and Subsidiaries Consolidated Financial Statements and Report of Independent Accountants December 31, 2013 and 2012

FARGLORY LAND DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. AND SUBSIDIARIES CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND REPORT OF INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTANTS DECEMBER 31, 2013 AND 2012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ For the convenience of readers and for information purpose only, the auditors’ report and the accompanying financial statements have been translated into English from the original Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. In the event of any discrepancy between the English version and the original Chinese version or any differences in the interpretation of the two versions, the Chinese-language auditors’ report and financial statements shall prevail. New Standards, Interpretations and Amendments Main Amendments IASB Effective Date Limited exemption from The amendment provides first-time adopters of IFRSs July 1, 2010 comparative IFRS 7 disclosures with the same transition relief that existing IFRS for first-time adopters preparers received in IFRS 7, ‘Financial Instruments: (amendment to IFRS 1) Disclosures’ and exempts first-time adopters from providing the additional comparative disclosures. Improvements to IFRSs 2010 Amendments to IFRS 1, IFRS 3, IFRS 7, IAS 1, IAS 34 January 1, 2011 and IFRIC 13. IFRS 9, ‘Financial instruments: IFRS 9 requires gains and losses on financial liabilities November 19, 2013 Classification and measurement designated at fair value through profit or loss to be split (Not mandatory) of financial liabilities into the amount of change in the fair value that is attributable to changes in the credit risk of the liability, which shall be presented in other comprehensive income, and cannot be reclassified to profit or loss when derecognising the liabilities; and all other changes in fair value are recognised in profit or loss. -

Study on the Strategies of Regional Cooperative Funeral Facilities: a Case Study of New Taipei City, Taiwan

International review for spatial planning and sustainable development A: Planning Strategies and Design Concept, Vol.7 No.1 (2019), 155-176 ISSN: 2187-3666 (online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14246/irspsda.7.1_155 Copyright@SPSD Press from 2010, SPSD Press, Kanazawa Study on the Strategies of Regional Cooperative Funeral Facilities: A Case Study of New Taipei City, Taiwan Meng-Ju Lin 1, Kuang-Hui Peng1* and Lih-Yau Song1 1 College of Design, National Taipei University of Technology * Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected] Received: 8 May 2018; Accepted: 3 Sep 2018 Key words: Funeral Facilities, Regional Cooperation, Time Series, Service Radius, Fishbone Diagram Abstract: For a long time, funeral facility sites and management by the local government in Taiwan have been lacking cross-regional resource integration and location- based research. As a result, funeral facility locations have become inappropriate, excessive or insufficient in supply, etc. New Taipei City is located adjacent to Taipei City and Keelung City. The number of funeral facilities is as high as 264. How to plan funeral facilities appropriately and in cooperation with neighboring local governments has become an important issue for the New Taipei City government. This study reviews the theory of regional cooperation, and the main topic of the research is the public columbarium buildings and public cemeteries in New Taipei City. In addition, the service radius of funeral facilities in the three cities is studied to identify both service area and distribution, as while as using a time series model to estimate the supply and demand situation of public cemeteries and public columbarium buildings. -

Taipei Q2 2020

M A R K E T B E AT TAIPEI Office Q2 2020 12-Mo. Forecast Overall Vacancy Rate Marks Ten-Year Low The office market’s overall vacancy rate declined 0.4 percentage points q-o-q to 4.4% in Q2, marking a ten-year low. By submarket, the Western 2,600 District experienced the biggest drop of 5.6 percentage points q-o-q, other districts moving less so. The Taiwan Life Insurance Zhongshan Building Average Rent (NTD/PING/MO) in Western performed well in leasing take-up, having entered the market only two quarters ago. Most of its tenants have relocated from the surrounding area, such as Sony Taiwan, which took 1,300 pings of space, relocating from the Changchun Financial Building. 0.6% Rental Growth Rate (QOQ) Average Rent Continues Rise Average rent for Grade A office space rose 0.6% in Q2 at NT$2,600 per ping per month, marking a ten-year high. Xinyi District led the way with 4.4% NT$3,190 per ping per month, with Taipei 101 recording a leasing record of more than NT$4,000 per ping per month. Xinyi’s high rental levels are Vacancy Rate still supported by sustained demand. In the low-supply environment, some tenants shifted to leasing co-working spaces in lieu of Grade A offices, Source: Cushman & Wakefield Research such as LINE Bank, which has located in JustCo Dian Shih. With the recent tight supply of leasable Grade A office space, the overall Taipei market remains as a landlords’ market, with overall high rental levels. -

Vertical Facility List

Facility List The Walt Disney Company is committed to fostering safe, inclusive and respectful workplaces wherever Disney-branded products are manufactured. Numerous measures in support of this commitment are in place, including increased transparency. To that end, we have published this list of the roughly 7,600 facilities in over 70 countries that manufacture Disney-branded products sold, distributed or used in our own retail businesses such as The Disney Stores and Theme Parks, as well as those used in our internal operations. Our goal in releasing this information is to foster collaboration with industry peers, governments, non- governmental organizations and others interested in improving working conditions. Under our International Labor Standards (ILS) Program, facilities that manufacture products or components incorporating Disney intellectual properties must be declared to Disney and receive prior authorization to manufacture. The list below includes the names and addresses of facilities disclosed to us by vendors under the requirements of Disney’s ILS Program for our vertical business, which includes our own retail businesses and internal operations. The list does not include the facilities used only by licensees of The Walt Disney Company or its affiliates that source, manufacture and sell consumer products by and through independent entities. Disney’s vertical business comprises a wide range of product categories including apparel, toys, electronics, food, home goods, personal care, books and others. As a result, the number of facilities involved in the production of Disney-branded products may be larger than for companies that operate in only one or a limited number of product categories. In addition, because we require vendors to disclose any facility where Disney intellectual property is present as part of the manufacturing process, the list includes facilities that may extend beyond finished goods manufacturers or final assembly locations.