Ohio's Risky Foray Into Bitcoin: Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cybersecurity: Should the SEC Be Sticking Its Nose Under This Tent?

Cybersecurity: Should the SEC be Sticking its Nose Under this Tent? By Loren F. Selznick and Carolyn LaMacchia1 A. Introduction On January 29, 2015, Anthem, Inc. learned of a cyberattack that occurred over the course of several weeks. Anthem, the country’s second-largest health insurer, reported unauthorized access to a database containing 80 million customer and employee records. Critical information accessed included Social Security numbers, birthdays, street and email addresses, and income data. Working closely with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the company has taken corrective measures, but the attackers have not been identified.2 According to media reports, Anthem will soon deplete its $100 million cyber- insurance coverage just to notify the victims and provide free identity-theft protection and credit monitoring in the wake of this breach.3 Anthem’s predicament is commonplace— managing a loss that is not readily apparent, unpredictable, and costly. With more business operations dependent upon technology, cybersecurity breaches occur on a daily basis and impact entities of all sizes. Investors envision similar cybersecurity breaches at their own companies. What if hackers obtained the debit and credit card information of retail customers? What if the cloud storage the company maintained for clients were breached? What if medical 1 Dr. Selznick (J.D. Cornell University) is an Assistant Professor of Business Law and Dr. LaMacchia (Ph.D. Nova Southeastern University) is an Assistant Professor of Information and Technology Management at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. 2 AnthemFacts.com, How to Access & Sign up for Identity Theft Repair & Credit Monitoring Services, https://www.anthemfacts.com (last visited Oct. -

An Empirical Analysis of the Black Market Exchange Rate in Iran

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Commerce - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Business and Law March 2004 An Empirical Analysis of the Black Market Exchange Rate in Iran Abbas Valadkhani University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers Part of the Business Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Valadkhani, Abbas: An Empirical Analysis of the Black Market Exchange Rate in Iran 2004. https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/395 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] An Empirical Analysis of the Black Market Exchange Rate in Iran Abstract The Iranian rial has been depreciated on average about 13 per cent per annum against the U.S dollar during the last four decades. This paper examines the long- and short-run determinants of the black market exchange rate employing the cointegration techniques and the annual time series data from 1960 to 2002. Consistent with previous studies and the monetary approach to the exchange-rate determination, it is found that the black market exchange rate is cointegrated with the relative consumer price indices in Iran and the U.S., real GDP and the relative import prices. However, in the short run only the rising relative prices and a meagre real GDP growth have been responsible for the depreciation of Iranian currency. Keywords Black market, exchange rate, Iran, Cointegration Disciplines Business | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details This article was originally published as Valadkhani, A, An Empirical Analysis of the Black Market Exchange Rate in Iran, Asian-African Journal of Economics and Econometrics, 4(2), 2004, 141-52. -

Cryptoportal,Kein Grosser Schritt Für Die Menschheit

Cryptoportal „Das Cryptoportal bietet Lehrern eine Plattform, auf der sie Unterrichtsmaterialien zum Thema Informationssicherheit und Kryptologie veröffentlichen und darüber diskutieren können. Dadurch sollen gegenseitige Anregungen und Hilfen sowohl für Lehrer als auch für Lernende entstehen.“ Kein grosser Schritt für die Menschheit …aber ein großer für Burks, um mit vmware klarzukommen. Gnome läuft immer noch nicht richtig oder ich sehe es nicht (ich vermute, es gibt ein Problem mit der Grafikkarte), aber immerhin kann ich normale Ubuntu-Programme wie gedit oder auch Firefoy mittlerweile im Fenster lassen, warum auch immer. (Wenn gedit funktioniert, dann müsste doch Gnome eigentlich installiert sei?) Frage: Es wäre doch eine lustige Idee, mit vmware einen Truecrypt-Container zu erzeugen, oder? Vmware und Gnome: Cannot open display Ich habe grad Gnome für Ubuntu per Vmware installiert, komme aber nicht weiter. Gnome will nicht starten. Hat jemand eine Idee? Das hier versteh ich nicht wirklich auf Anhieb. Avatar Film Allegedly Causing Depression „I got depressed when i watch star wars. i wanted a R2D2. so what i did was plug my toaster in and talk to it, and felt better.“ (Quelle) Schutztruppen und fanatisierte mohammedanische Neger Deutsche Kulturbilder der Berliner Morgenpost November 1929 – diese „Postkarte“ ist eine Quittung der Berliner Morgenpost „über 60 Pfennig für die 48. Woche vom 14.11. bis 30.11.1929“. Nicht jeder wird wissen, in welchem historischen Zusammenhang der Begriff „Schutztruppen“ steht, den unsere mental gleichgeschalteten Medien für die alliierten Besatzertruppen – darunter die Bundeswehr – in Afghanistan benutzen. Dieses „Kulturbild“ beschäftigt sich mit Georg Schweinfurth und Gustav Nachtigal, beides so genannte „Afrika-Reisende“ bzw. -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

Treasury Designates Iran- Based Financial Facilitators of Malicious

An official website of the United States Government U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY SECRETARY MNUCHIN ABOUT TREASURY POLICY ISSUES DATA SERVICES NEWS SEARCH HOME NEWS PRESS RELEASES NEWS PRESS RELEASES LATEST NEWS Press Treasury December 7, 2018 Releases OFAC Extends Designates Iran- Expiration Date of Statements General Licenses & Related to EN+, Remarks Based Financial RUSAL, and GAZ Facilitators of Readouts December 4, 2018 Postal Task Force Testimonies Malicious Cyber Activity and for Releases Report Featured Stories the First Time December 3, 2018 Remarks by Craig Press Identifies Phillips, Counselor to Contacts the Secretary, on Associated Digital Market Structure Report to President Currency Trump on Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Addresses Choice and Competition Under Secretary Sigal November 28, 2018 Mandelker Remarks ABA/ABA Financial Crimes Enforcement WASHINGTON – The U.S. Department of the Conference December Treasury’s O!ice of Foreign Assets Control 3, 2018 (OFAC) took action today against two Iran- based individuals, Ali Khorashadizadeh and Mohammad Ghorbaniyan, who helped exchange digital currency (bitcoin) ransom payments into Iranian rial on behalf of Iranian malicious cyber actors involved with the SamSam ransomware scheme that targeted over 200 known victims. Also today, OFAC identified two digital currency addresses associated with these two financial facilitators. Over 7,000 transactions in bitcoin, worth millions of U.S. dollars, have processed through these two addresses - some of which involved SamSam ransomware derived bitcoin. In a related action, the U.S. Department of Justice today indicted two Iranian criminal actors for infecting numerous data networks with SamSam ransomware in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada since 2015. -

The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 Full Episode

The good wife season 5 episode 1 full episode Crime · Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own The Good Wife (–). / 1 user 1 critic Season 5 | Episode 1. Previous . HD. See full technical specs». Edit. The Good Wife: Everything is Ending - on on CBS All Access. Season 5: Episode 1 - Everything is Ending Full Episodes. Blue Bloods Video - Cutting Losses (Sneak Peek 1). Undo. Get Ready To Watch Even More Young Sheldon! - Undo. How To Watch Criminal Minds. Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own firm with Cary, but people begin to suspect something is afoot. The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 2 The Good. Watch The Good Wife: Everything Is Ending from Season 5 at Watch The Good Wife - Season 5, Episode 1 - Everything is Ending: Alicia tries to balance one final Watch Full Episodes: The Good Wife. Watch The Good Wife S05E01 Season 5 Episode 1. Season 1. watch all episodes The Good Wife Season. The Good Wife - Season 5 The fifth season of the legal drama begins with Alicia and Episode 1: Everything is Ending Episode 2: The Bit Bucket Episode 3: A. Trailer; Episode 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19 . Watch The Good Wife Season 5 putlocker9 Full Episode Online. -

The Good Wife Season 1 Episod 11 Free Download Watch the Good Wife Online

the good wife season 1 episod 11 free download Watch The Good Wife Online. You have found a great place to watch The Good Wife online. TV Fanatic has many options available for your viewing pleasure so watch The Good Wife online now! On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 22, Alicia must decide what she'll do next as a verdict is reached in Peter's trial on the series finale. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 21, as the trial unfolds, new accusations come out and Alicia works furiously to keep Peter from going back to jail. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 20, everything goes wrong at a party to celebrate Howard and Jackie's upcoming wedding while Eli asks Jason to investigate Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 19, Peter faces possible arrest while Alicia and Lucca fly to Toronto to represent an NSA agent detained by customs. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 18, the power struggle at Lockhart, Agos & Lee reaches a boiling point, and Marissa is used as leverage in the case against Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 17, the firm defends a father of a shooting victim when he puts up a billboard calling a gun store owner a murderer. What's Diane's plan for the firm? What does the FBI have on Peter? Check out our recap and review of The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 16. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 15, Eli hires Elsbeth Tascioni to find out why the FBI is after Peter while Alicia joins a secret panel of attorneys on a case. -

GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King

THE GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King January 29, 2009 TEASER A VIDEO IMAGE of... ...a packed press conference. A lower-third chyron trumpets “Chicago D.A. Resigns” as the grim D.A. approaches a podium, his wife beside him. He clears his throat, reads: DAVID FOLLICK Good morning. An hour ago, I resigned as States Attorney of Cook County. I did this with a heavy heart and a deep commitment to fight these scurrilous charges. At the same time, I need time to atone for my private failings with my wife, Alicia, and our two children. Oh, one of those press conferences. Scandal. In the key of Elliott Spitzer. DAVID FOLLICK (40) is a back-slapping Bill Clinton: smart, funny, calculatedly seductive, and now at the end of his career. But he’s not our hero. Our hero is... ...his wife, ALICIA (late-30s) standing beside him. Pretty. Proper. She’s always been the good girl-- the good girl who became the good wife, then the good mom: devoted, struggling not to outshine her husband. We move in on her as we hear... DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) I want to be clear. I have never abused my office. I have never traded lighter sentences for either financial or sexual favors. Ugh. We suddenly enter the video, and we’re there with... Alicia as she looks out at the excited reporters, the phalanx of cameras all clicking, boring in on her. DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) But I do admit to a failure of judgment in my private dealings with these women. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Iran's Price Precipice

Iran’s Price Precipice Understanding the drivers behind Iran’s skyrocketing inflation and its impact on the population. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Findings: The official inflation rate in Iran increased from 7% in March 2018 to 42.5% in February 2019. Over the same period, the USD/IRR free-market rate increased by 170%. The situation has resulted in a colossal rise in consumer prices, heavily impacting Iranians’ purchasing power. • Explanation: While the IRR’s devaluation on the free market has certainly impacted price levels, the immediate drivers behind the rapidly increasing prices are the currency peg and the government’s mismanagement of the economic crisis. • The Economist View: The Iranian state is growing more anti-free market and increasing its intervention in the economy, thus harming its future prospects. • Living in Iran: From E-Coupons to queues in meat shops, the US’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) has directly impacted Iranians’ livelihoods. • Poverty Rate: On the back of rising consumer prices the poverty threshold for a family of four in Tehran increased by at least $44 in 2018, bringing many Iranians under the poverty line. Who are we? Castlereagh Associates is a research and analysis company, providing clients with key insights to support their decision-making and enable them to build more competitive and resilient businesses on national, regional and global levels. Copyright © 2019 Castlereagh Associates- All Rights Reserved. Credits: Copyright © Shutterstock ECONOMIC RISK SERIES NO.3 | MAY 2019 IRAN’S PRICE PRECIPICE Inflation Rate: Official Inflation Rate 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Figure 1. -

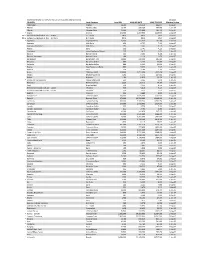

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates for Fellows And

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Sep 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date Afghanistan Afghani 12,500 131,250 196,875 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 13,100 206,325 309,488 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 134,000 1,407,000 2,110,500 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 19,700 162,525 243,788 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 680 6,630 9,945 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 Bolivia Boliviano 1,180 10,620 15,930 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 264 3,366 5,049 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr.