Tawny Frogmouth Husbandry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Life and Adaptations

4 Daily life and adaptations Tawny frogmouth behaviour still poses many questions. This and the following chapters are by no means exhaustive but they provide a window into the night and day life of tawny frogmouths. Much is intriguing and unusual about tawny frogmouths. Lifespan and interventions It is not known how long tawny frogmouths actually live in the wild. Banding records of a small sample of 107 recovered birds showed that the oldest was 165 months or 13.75 years of age.1 Some zoo records might have information on lifespan in captivity but this raises further questions. Captivity can have seriously detrimental effects on lifespan (shortening it) or, at times, may prolong life well beyond normal life expectancy in the wild, making the two sets of data not easily comparable. The data on captive tawny frogmouths, as sparse as they are, certainly suggest a potential for a very long lifespan, if one thinks of the recent report from London Zoo of having to euthanase a tawny frogmouth at the age of 32 years. And then there is the individual adult male rescued in 1994 in New South Wales that is still alive in 2017 at the time of writing the revised copy of this book. Getting accurate records of optimal lifespan in the wild is not easy for any species. Many birds die well before they reach reproductive age and even those who survive on their own into adulthood can meet with misadventure, especially in modern society with its many civilisation risks. Tawny frogmouths feeding on 171221 Tawny Frogmouth 2nd Ed. -

Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus Strigoides)

Bush B Volume 1 u d d i e s Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) When it’s not mistaken for an owl, the Tawny Frogmouth can easily be confused with a tree branch! With narrowed eyelids and a stretched neck, this bark-coloured bird is a master of camouflage. Tawny Frogmouths are between 34cm (females) and 53cm (males) long and can weigh up to 680g. Their plumage is mottled grey, white, black and rufous – the feather patterns help them mimic dead tree branches. Their feathers are soft, like those of owls, allowing for stealthy, silent flight. They have stocky heads with big yellow eyes. Stiff bristles surround their beak; these ‘whiskers’ may help detect the movement of flying insects, and/or protect their faces from the bites or stings of distressed prey (this is not known for certain). Their beak is large and wide, hence the name frogmouth. Their genus name, Podargus, is from the Greek work for gout. Why? Unlike owls they don’t have curved talons on their feet; in fact, their feet are small, and they’re said to walk like a gout-ridden man! Their species name, strigoides, means owl-like. They’re nocturnal and carnivorous, but Tawny Frogmouths aren’t owls – they’re more closely related to Nightjars. There are two other species of frogmouth in Australia – the Papuan Frogmouth (Podargus papuensis) lives in the Cape York Peninsula, and the Marbled Frogmouth (P. ocellatus) is found in two well-separated races: one in tropical rainforests in northern Cape York and the A Tawny Frogmouth disguised against the bark of a tree at Naree in NSW. -

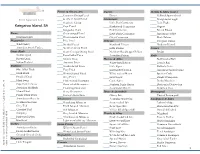

Bird Species Checklist

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

The Rainbow Bird

The Rainbow Bird Volume 6 Number 1 February 2017 (Issue 89) In this Issue Symbiosis Page 2 Willie Wagtails Page 5 The Sad Death of a Page 6 Kingfisher My Bird Page 8 White-eared Page 9 Honeyeaters Who is Robert Hall? Page 10 Black and White Birds Page 12 Challenge Count 2016 Page 13 Glossy Ibis Page 14 Grey Teal Page 15 Striated Pardalotes Page 16 Sparrowhawks Page 17 Wind beneath their Page 18 Wings Young Spoonbills Page 19 Species Profile Page 20 Hotspot Profile Page 23 1 The Challenge Page 25 Sightings and Calendar Page 26 The Rainbow Bird Photo acknowledgements for title page: Symbiosis Allan Taylor, Lindsay Cupper, Ken Job, Pauline I was recently handed a copy of the Sunraysia Naturalists’ Follett, Richard Wells, Research Trusts’ 1975/76 report by Helen. This will be kept in Finley Japp. the cabinet that holds the books of the Favaloro collection. The report covers a year which seems to be one of the best for sighting birds in recent memory. Part of the report details the Trust members’ observations on the bird nests in the Tapio area just north of Hollands Lake. There were large numbers of White-browed Woodswallow and Masked Woodswallow nests constructed close to each other and to those of Black-faced Cuckoo-Shrikes. Apparently, this behaviour is well-known but I don’t know the reason for it. The article got me thinking about Symbiotic Relationships. When referring to relationships between flora and fauna, it is common to sub-divide these relationships into Mutualistic; Commensalistic; and Parasitic relationships. -

Carnaby's Black-Cockatoo M Galah M Long-Billed Corella R Little Corella M Rainbow Lorikeet C Australian Ringneck C Red-Cap

WATERFOWL Australian White Ibis C Carnaby's Black-Cockatoo M Musk Duck C Straw-necked Ibis M Galah M Freckled Duck R Yellow-billed Spoonbill M Long-billed Corella R Black Swan C Little Corella M Australian Shelduck M RAPTOR Rainbow Lorikeet C Australian Wood Duck M Black-shouldered Kite C Australian Ringneck C Pink-eared Duck M White-bellied Sea-Eagle R Red-capped Parrot M Australasian Shoveler C Whistling Kite M Elegant Parrot R Grey Teal C Brown Goshawk M Pacific Black Duck C Collared Sparrowhawk M CUCKOO Hardhead M Swamp Harrier C Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo R Blue-billed Duck M Little Eagle M Shining Bronze-Cuckoo U Nankeen Kestrel M Fan-tailed Cuckoo M GREBE Australian Hobby U Australasian Grebe C Peregrine Falcon R OWL Hoary-headed Grebe M Southern Boobook U Great Crested Grebe M CRAKE, RAIL, ALLIES Purple Swamphen C KINGFISHER PIGEON, DOVE Buff-banded Rail M Laughing Kookaburra M Rock Dove U (Feral Pigeon) Baillon's Crake U Sacred Kingfisher M Laughing Dove C Australian Spotted Crake U Spotted Dove C Spotless Crake M BEE-EATER, ROLLER Common Bronzewing R Dusky Moorhen C Rainbow Bee-eater M Crested Pigeon U Eurasian Coot C FAIRY-WREN, GRASSWREN FROGMOUTH SHOREBIRD Splendid Fairy-wren C Tawny Frogmouth U Black-winged Stilt C Banded Stilt U SCRUBWREN, ALLIES CORMORANT Red-necked Avocet U White-browed Scrubwren U Australasian Darter M Black-fronted Dotterel M Weebill U Little Pied Cormorant M Red-kneed Dotterel R Western Gerygone C Great Cormorant M Common Sandpiper U Yellow-rumped Thornbill C Little Black Cormorant M Common Greenshank -

Grand Australia Part I: New South Wales & the Northern Territory September 28–October 14, 2019

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART I: NEW SOUTH WALES & THE NORTHERN TERRITORY SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 14, 2019 A knock out Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove we found in Darwin perched out unusually brazenly. LEADERS: DION HOBCROFT AND JANENE LUFF LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Our Australia tours have become so popular that we ran two VENT departures this year around the continent. The first was led by great birding friend and outstanding leader Max Breckenridge, well assisted by Barry Zimmer, one of our most highly regarded leaders. Janene and I led the second departure starting a week later. As usual, we started in Sydney at a comfortable hotel close to city attractions like the Opera House, Botanic Gardens, Art Gallery, and various museums. This included some good birding sites like Sydney Olympic Park some five miles west of the city. This young male Superb Lyrebird came walking past us in rainforest at Royal National Park. Our tour began with great cool weather, and in the park we were soon amongst the attractions with nesting Tawny Frogmouth a good start. There were plenty of waterbirds including Black Swan, Chestnut Teal, Hardhead, Australasian Darter, four species of cormorants, and three species of large rails (swamphen, moorhen, and coot). On the tidal lagoon, good numbers of Red-necked Avocets mingled about with a small flock of recently arrived migrant Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, while a dapper pair of adult Red-kneed Dotterels was very handy. Participants were somewhat “gobsmacked” by colorful Galahs, Rainbow Lorikeets, raucous Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, and their smaller cousin the Little Corella. -

The Song of the Dulit Frogmouth Batrachostomus Harterti

Forktail 26 (2010) SHORT NOTES 141 seen incubating eggs first on 11 April 2009 in a nest in a species to assess if cronism is commoner than suggested eucalyptus tree, and subsequently four newly hatched by the literature. chicks were seen on 7 May 2009. On 18 May 2009, the female adult (told by her yellow eyes) brought a five- striped palm squirrel Funambulus palmarum to the nest ACKNOWLEDGEMENT and fed pieces of the squirrel to all four chicks. The following evening there was a dust storm that damaged We thank L. Shyamal for assistance with references and a discussion on the nest. The next day, only one chick could be seen in the cronism. We thank two anonymous referees and Nigel Collar for their nest and a male Shikra (told by his red eyes) was seen critique on a previous draft of the note. feeding on one of the chicks near the nest. The female called loudly as the chick was being eaten, and the male flew to the nest tree after eating the chick. This suggested REFERENCES that the male in question was the chick’s parent. It was not clear if the chick had been killed by the male or had Dawson, R. D. & Bortolotti, G. R. (2000) Reproductive success of died during the storm and was subsequently eaten, but American Kestrels: the role of prey abundance and weather. Condor we think the latter more probable. The other two missing 102: 814–822. chicks were not found; since they had not yet fledged, Dios, I. S. G. -

Bird A) the Article Says the Most Popular Photos to Put Online Are of Breakfasts

BreakingNewsEnglish - Many online quizzes at URL below Researchers find most True / False 'instagrammable' bird a) The article says the most popular photos to put online are of breakfasts. T / F 4th May, 2021 b) The article says some Instagram posts stay online for over 24 hours. T / F It seems we share photos online of c) The research is from a university in Germany. everything these days, T / F from what we eat for d) Researchers found the most 'instagrammable' breakfast to the new bird to be the mouthfrog. T / F shoes we have bought. Researchers have e) Researchers looked at over 30,000 photos of recently published a birds in their research. T / F study about what kinds f) Researchers used a special algorithm to find of bird photos we like the 'best' bird. T / F on the social media site Instagram. This is a photo and video-sharing social g) The 'winning' bird has big eyes and a narrow networking service on which uploaded images are beak. T / F viewable for just 24 hours. The researchers are h) A photographer said animals with large eyes from the University of Konstanz in Germany. They are cute and cuddly. T / F looked into the question: "What makes a great bird photo?" They tried to find the most 'instagrammable' bird. They discovered that the Synonym Match frogmouth is our favourite. This is a nocturnal bird (The words in bold are from the news article.) that is found from India, across Southeast Asia to 1. seems a. examined Australia. 2. study b. -

Borneo Trip Report Black Oriole and Dulit Frogmouth Extension Th Nd 27 June to 2 July 2015

Borneo Trip Report Black Oriole and Dulit Frogmouth Extension th nd 27 June to 2 July 2015 The beautifally plumaged Blue-banded Pitta at Mererap by Rosemary Loyd. RBT Trip Report – Borneo Black Oriole & Dulit Frogmouth Extension 2015 2 Tour Leaders: Ch’ien C. Lee and Erik Forsyth Trip report compiled by Tour Leader Erik Forsyth Tour Summary “It wasn’t long before we again heard the unmistakable high-pitched fluty call of the Black Oriole, a species few birders have heard, let alone seen. And within a few magical seconds a bird appeared on an open twig, its black plumage and bright-red bill strikingly noticeable in the early morning sunshine. Then suddenly a second bird joined in and we were treated to fabulous views. This is the bird we had come so far to see and boy did we see the pair well!” To hear about our trip into Sarawak, read on… On our first morning in Kota Kinabalu, we took a quick walk around the hotel grounds, picking up several of the commoner city birds including confiding Pink-necked Green Pigeons sunning in the early sunlight, Peaceful Dove, Glossy Swiftlet, a calling Asian Koel, Collared Kingfisher, Asian Glossy Starling and Yellow-vented Bulbul. Shortly after this we met our driver and jumped into the vehicle to take us to Lawas in Sarawak. South of Kota Kinabalu we stopped at several rice fields swarming with birds, where we found good numbers of Great, Intermediate and Little Egrets concentrated in certain flooded fields, the odd Purple Heron and Brahminy Kite, as well as a single, overwintering Common Greenshank. -

Bird Check List

BIRD CHECK LIST Emu Cuckoos & Coucal Pelicans Fan-tailed Cuckoo(h) Australian Pelica Eagles, Hawks & Harriers Horsfield’s Bronze cuckoo Black-shouldered Kite Pheasant Coucal Stilts, Avocets & Plovers Square-tailed Kit Black-winged Stilt Black Kite Cranes Black-fronted Dotteral Whistling Kite Brolga Masked Lapwing White-bellied Sea-eagle Swamp Harrier Grebes Herons, Egrets & Bitterns Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe(b) White-faced Heron(b) Collared Sparrowhawk Great Crested Grebe(b) White- necked Heron(b) Wedge-tailed Eagle Great Egret Little Eagle Owls & Night Birds Intermediate Egret Brown Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Nankeen Night Heron Peregrine Falcon Australian Nightjar Australian Hobby Treecreepers Nankeen Kestrel Crakes & Rails White-throated Treecreeper Purple Swamphen(b) Cockatoos & Parrots Dusky Moorhen(b) Pigeons & Doves Galah Eurasian Coot(b Emerald Dove (h) Sulphur- crested Cockatoo Darter & Cormorants Common Bronzewing (h) Rainbow Lorikeet Darter(b) Crested Pigeon Cockatiel Little Pied Cormorant(b) Squatter Pigeon Little Lorikeet Pied Cormorant Peaceful Dove Australian King Parrot Little Black Cormorant Bar-shouldered Dove Red-winged Parrot Wonga Pigeon(h) Pale-headed Rosella Swiftlets & Swifts Budgerigar White-throated Needletail Ibis, Spoonbills & Stork Fork-tailed Swift Australian White Ibis Quails Straw-necked Ibis Brown Quail Bustard Yellow-billed Spoonbill Bustard Geese, Ducks & Swan Fairy-wrens Plumed Whistling-duck(b) Kingfishers, Bee-eater & Superb Fairy-wren Wandering Whistling duck(b) Dollarbird Variegated Fairy-wren -

The Bird Department Has Over 141 'Pecies Represented by Over 900 Indi Vidual Birds Froin Australia and Around the World

The Melbourne Zoo Bird Department by Ian Smith, Senior Birdkeeper, Bird Department, Melbourne Zoo Victoria, Australia he Melhourne Zoo is one of only four major zoos in T Australia. It is also one of the largest, covering 52 acres, and is situated in the Illiddle of a large inner city parkland, and only five minutes hy car from the center of Melhourne. Animals from Australia and all over the world ar displayed in land 'caped enclosures. Sonle exhihits are located in Bio-Clirnatic zones which is the heginning of the zoo's masterplan. Tbe ,!!, rcat jlight ol'imy. This plan will 'ee the zoo divided into Bio-Climatic Zones, including Asian and African Rainforests and Australian Eucalypt Woodland. Each zone will have species of animals on display that are indigenous to the specific habitat. The Bird Department has over 141 'pecies represented by over 900 indi vidual birds froin Australia and around the world. Most are on display in a range of landscaped aviaries and open roofed exhibits, while a small number of birds are in the extensive off-limit quarantine and hospital complex. The bird displays are located around the zoo grounds and include aviaries, lakes, and ponds which are landscaped and planted to represent particular habitats, including Rainforest and Woodland. I would now like to take you on a tour of the bird displays at the Melbourne Zoo and show you our dis- / 1 l'iC'll' q/ tbe I(){'(!/Jird e.YbiIJit. Look c(/rc:/i"~~I./()r the !it/Ie birds. plays and collection. the afa \VATCI-IBIRD 47 J African Rainforest Our first stop is the African Rainforest where we climb a wooden boardwalk to the Arboreal Primate Complex. -

CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2

CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2: Review of Current Knowledge of Bird Flyways, Principal Knowledge Gaps and Conservation Priorities Compiled by: JEFF KIRBY Just Ecology Brookend House, Old Brookend, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, GL13 9SQ, U.K. September 2010 Acknowledgements I am grateful to colleagues at BirdLife International for the input of analyses, technical information, advice, ideas, research papers, peer review and comment. Thus, I extend my gratitude to my lead contact at the BirdLife Secretariat, Ali Stattersfield, and to Tris Allinson, Jonathan Barnard, Stuart Butchart, John Croxall, Mike Evans, Lincoln Fishpool, Richard Grimmett, Vicky Jones and Ian May. In addition, John Sherwell worked enthusiastically and efficiently to provide many key publications, at short notice, and I‘m grateful to him for that. I also thank the authors of, and contributors to, Kirby et al. (2008) which was a major review of the status of migratory bird species and which laid the foundations for this work. Borja Heredia, from CMS, and Taej Mundkur, from Wetlands International, also provided much helpful advice and assistance, and were instrumental in steering the work. I wish to thank Tim Jones as well (the compiler of a parallel review of CMS instruments) for his advice, comment and technical inputs; and also Simon Delany of Wetlands International. Various members of the CMS Flyway Working Group, and other representatives from CMS, BirdLife and Wetlands International networks, responded to requests for advice and comment and for this I wish to thank: Olivier Biber, Joost Brouwer, Nicola Crockford, Carlo C. Custodio, Tim Dodman, Muembo Kabemba Donatien, Roger Jaensch, Jelena Kralj, Angus Middleton, Narelle Montgomery, Cristina Morales, Paul Kariuki Ndang'ang'a, Paul O‘Neill, Herb Raffaele, Fernando Spina and David Stroud.