'Where the Wild Things Are' Final Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trunk Road Estate Biodiversity Action Plan

Home Welsh Assembly Government Trunk Road Estate Biodiversity Action Plan 2004-2014 If you have any comments on this document, its contents, or its links to other sites, please send them by post to: Environmental Science Advisor, Transport Directorate, Welsh Assembly Government, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NQ or by email to [email protected] The same contact point can be used to report sightings of wildlife relating to the Trunk Road and Motorway network. Prepared by on behalf of the Welsh Assembly Government ISBN 0 7504 3243 8 JANUARY 2004 ©Crown copyright 2004 Home Contents Foreword by Minister for Economic Development and Transport 4 Executive Summary 5 How to use this document 8 Introduction 9 Background to biodiversity in the UK 10 Background to biodiversity in Wales 12 The Trunk Road Estate 13 Existing guidance and advice 16 TREBAP development 19 Delivery 23 Links to other organisations 26 The Plans 27 Glossary 129 Bibliography and useful references 134 Other references 138 Acknowledgements 139 3 Contents Foreword FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND TRANSPORT The publication of this Action Plan is both a recognition of the way the Assembly Government has been taking forward biodiversity and an opportunity for the Transport Directorate to continue to contribute to the wealth of biodiversity that occurs in Wales. Getting the right balance between the needs of our society for road-based transport, and the effects of the Assembly’s road network on our wildlife is a complex and often controversial issue. The Plan itself is designed to both challenge and inspire those who work with the Directorate on the National Assembly’s road network – and, as importantly, to challenge those of us who use the network to think more about the wildlife there. -

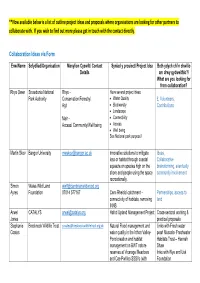

Now Available Below Is a List of Outline Project Ideas and Proposals Where Organisations Are Looking for Other Partners to Collaborate With

**Now available below is a list of outline project ideas and proposals where organisations are looking for other partners to collaborate with. If you wish to find out more please get in touch with the contact directly. Collaboration Ideas via Form Enw/Name Sefydliad/Organisation Manylion Cyswllt/ Contact Syniad y prosiect/ Project Idea Beth ydych chi’n chwilio Details am drwy gydweithio?/ What are you looking for from collaboration? Rhys Owen Snowdonia National Rhys – Have several project ideas: Park Authority Conservation/Forestry/ Water Quality £, Volunteers, Agri Biodiversity Contributions Landscape Mair – Connectivity Access/ Community/Well being Access Well being See National park purpose! Martin Skov Bangor University [email protected] Innovative solutions to mitigate Ideas, loss or habitat through coastal Collaborative squeeze on species high on the brainstorming, eventually shore and people using the space community involvement recreationally. Simon Wales Wild Land [email protected] Ayres Foundation 07814 577167 Cwm Rheidol catchment – Partnerships, access to connectivity of habitats, removing land INNS Arwel CATALYS [email protected] Hafod Upland Management Project Cross-sectoral working & Jones practical proposals Stephanie Brecknock Wildlife Trust [email protected] Natural Flood management and Links with Fresh water Coates water quality in the Irthon Valley- pearl Mussels- Freshwater Pond creation and habitat Habitats Trust – Hannah management on BWT nature Shaw reserves at Vicarage Meadows links with Wye and Usk and Cae Pwll bo SSSI’s (with Foundation consent from NRW due to meet January) Mike Kelly Shropshire Hills AONB [email protected] Upper Teme Wildlife/Habitat Bridge: We are currently working with Partnership 01743 254743 Natural England to develop this The upper River Teme forms the project in the Upper Teme boundary between Powys and Catchment. -

English Nature Research Report

LOCAL'REGIONAL BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLANS Plan name c. "K;IOL'JJ:: Ref. No Area $,:rev countv Regton CC.JTH LAST Organisations involved SJrrey WT Coordinating Surrey County Council Coordinating E-gltsh Nature Funding ~5x3 source of information 7#*/AG Source of information Eiv Age C:k WWF-UK and Herpetological Consewation Trust Purpose Outline long term (50 yrs) vision for arEa set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience Local CouncillorIdecisionmakers Timescale First draft Contact Jtil Barton IDebbie Wicks Surrey Wildlife Trust 01 483 488055 -~"__--_I-___"___- I --_I--.-- - Plan name Unknown Ref. No. Area Greater London Region SOUTH EAST Organisations involved Role London Wildlife Trust Coordinating London Ecology URlt Coordinating ENIEA Coordinating 3TCVIRSPB Coordinating WTINat.His. Soc. Source of information Tne above make up the steering group together vvlth another Six Purpose Outline long term (50 yrs) vision for area Set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience General public Conservation staff in paltnerirelated organisations Local CouncillorIdecisionmakers Mern bersivolunteers Timescale Unknown Contact Ralph Gaines London Wildlife Trust 0171 278 661213 __-______-_I ~ ---^_---_--__-+_-- +"." ---I--7-_-_+ 01 '20198 Page 27 LOCAURECIONAL BlODlVERSlTY ACTION PLANS Plan name UnKfiOVIC Ref. No. Area ilmpsnire county Region SCUTH EAST Organisations involved Role Hampshire Wildlife Trust Caord!nating Hampshire County Council Coordinating Local Authorities Funding Engllsh Nature ' Env Age Source of information RSPB Source of information CLA NFU CPRE.FA.FE Purpose Set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience General public Local CouncillorIdecision makers Timescale First drafi Audit planned summer 1998 Contact Patrick Cloughley Hampshire and IOWWildlife Trust 01 703 61 3737 -___ , _____.__x """ ____---I_--_____-__I ___-_I ---_ ~ ".... -

Recorders' Newsletter Issue 24 – November 2017 Contents

Unit 4, 6 The Bulwark, Brecon, Powys, LD3 7LB Recorders’ Newsletter 01874 610881 [email protected] www.bis.org.uk Issue 24 – November 2017 Facebook: @BISBrecon Welcome to the 2017 autumn edition of the BIS newsletter. In this bumper edition there are exciting articles on ladybirds, Hairy Dragonflies, Pearl-Bordered and Marsh Fritillaries, reviews of 2016 for Breconshire Birds and Brecknock Botany Group along with further ins and outs at BIS and our second Recorder of the Season. On page 19 is the programme for this year’s Recorders Forum on 28th November. Thank you to all of you who have contributed to this issue, we hope you all enjoy it. Please contact [email protected] for any questions, comments or ideas for future content. Contents Article Page BIS Update 2 Where the Wild Things Are 3 Skullcap Sawfly 3 Breconshire Bird Report for 2016 4 Llangorse Hairy Dragonfly 5 Penpont Fungal Foray 5 A Dung Beetle first 6 Black Mountains Land Use Partnership 6 A butterfly on the edge – Pearl Bordered Fritillary 7-8 New at BIS 9 Lovely Ladybirds 9 Dragonfly walk on the Begwns 10 Clubtail Survey 10 Marsh Fritillary Success 11 Wonderful Waxcaps 11 Llangorse Lake Wetland Mollusc Hunt 12-13 New Moths for Spain 13 Recorder of the Season 14 Brecknock Botany Report 15-16 Long Forest Launch 17 BIS Events 18 Recorders Forum 2017 Programme 19 Useful Links 20 Page 1 of 20 BIS Update Arrivals & Departures Welcome to Ben Mullen who has recently taken on the role of Communications Officer. Ben hit the ground running with enthusiastic new ideas to promote recording and editing this newsletter. -

Access Leaflet

PowAccesysibs le A Guide to Countryside Trails and Sites 1st Edition Accessible Powys A Guide to Countryside Trails and Sites contain more detailed accessibility data and Also Explorer Map numbers and Ordnance We have made every effort to ensure that the Introduction updated information for each site visited as well Survey Grid references and facilities on site information contained in this guide is correct at as additional sites that have been visited since see key below: the time of printing and neither Disabled Welcome to the wealth of countryside within publication. Holiday Information (nor Powys County Council) the ancient counties of Radnorshire, on site unless otherwise stated will be held liable for any loss or Brecknockshire and Montgomeryshire, The guide is split into the 3 historic shires within NB most designated public toilets disappointment suffered as a result of using the county and at the beginning of each section which together make up the present day will require a radar key this guide. county of Powys. is a reference to the relevant Ordnance Survey Explorer maps. at least one seat along route This guide contains details of various sites and trails that are suitable for people needing easier Each site or trail has been given a category accessible picnic table access, such as wheelchair users, parents with which gives an indication of ease of use. small children and people with limited Category 1 – These are easier access routes tactile elements / audio interest walking ability. that are mainly level and that would be suitable We hope you enjoy your time in this beautiful for most visitors (including self propelling For further information on other guides or to and diverse landscape. -

BIS Newsl 9 May 2010.Pdf

Biodiversity Information Service Recorder Newsletter – Issue 7 – May 2009 RECORDERS NEWSLETTER ISSUE 9 – May 2010 Welcome to the ninth edition of the Powys and Brecon Beacons National Park recorders newsletter. In this issue, Bob Dennison describes the British Dragonfly Societies’ new online recording system; Phil Sutton adds an interesting note and photo of a harvest mouse nest barbeque; Tammy Stretton enthuses us with the Montgomeryshire Wildlife Sites Project; for those more computer minded, our own Michelle Weinhold describes the recent predictive modelling project she has undertaken at BIS on horseshoe bats; yours truly comments on the lily beetle in Powys; and a request by Butterfly Conservation to help search for the Forester moth in Wales. Don’t forget to come along on the Recording Day at Abergwesyn Common on 24th July. Good hunting! Phil Ward – Editor Training day Penlan ponds (Keith Noble) Lily beetle Lilioceris lilii (Keith Noble) Contents Update from BIS Janet Imlach 2 Priceless Dragonfly and Damselfly Records! Bob Dennison 3 New Montgomeryshire Dragonfly Recorder needed 4 Harvest Mouse Micromys minutus nest Phil Sutton 5 Abergwesyn Commons Recording day Jessica Tyler 6 Predictive Modelling Project at BIS Michelle Weinhold 7 1st Lily Beetle record for Powys? Nearly! Phil Ward 9 BIS database reaches one million records! Janet Imlach 10 Montgomeryshire Wildlife Sites Project 2006-2010 Tammy Stretton 11 Photo page 13 BIS Wildlife Recording Training Days 2010 14 Butterfly Conservation request – Forester moth Butterfly Conservation 17 BIS contact details 18 Page 1 of 18 Biodiversity Information Service Recorder Newsletter – Issue 7 – May 2009 BIS update Staff Time has passed by very quickly as in the last newsletter we said hello to Naomi Stratton, who worked with us on a Go Wales placement and then stood in for Anna while she is on maternity leave. -

Countryside Jobs Service

Countryside Jobs Service Focus on Volunteering In association with Keep Britain Tidy 13 February 2017 Keeping Britain Tidy – volunteering and spring cleaning National environmental charity Keep Britain Tidy biggest-ever litter campaign – the Great British Spring Clean – will culminate with a weekend of action next month. Between March 3rd and 5th, we are aiming to mobilise half a million people to get out and make their neighbourhood one of which they can be really proud. Yes, we’d love you to get involved. But we would really like you to involve others too. As countryside managers or workers, you may be ideally placed to help us get more people involved, and help yourself at the same time. As a charity, the public mostly recognise Keep Britain Tidy for our anti-litter campaigns but we do so much more. We work with schools, in green spaces, on beaches, in cities and communities, with businesses, local authorities and individuals. We run the country’s flagship school environmental programme, Eco-Schools, along with (Keep Britain Tidy) the Green Flag Award for parks and green spaces, the Blue Flag Award and Seaside Awards for beaches and the volunteer litter-picking programme the Big Tidy Up. You can find out more about everything we do via keepbritaintidy.org or find us on social media. Our army of 336,000 formal and informal volunteers help us on a daily basis to work towards our aims of eliminating litter, improving local places and ending waste. Without them we would not be able to make the difference we make every day. -

Conservation Team Report 2018 - 2019

Conservation Team Report 2018 - 2019 1 www.welshwildlife.org Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Members of the conservation team ......................................................................................... 3 1.2 Our assets ............................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Our funders ............................................................................................................................. 9 2. Nature Reserves ........................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Introduction to our work on our nature reserves ................................................................... 10 2.2 Habitat management ............................................................................................................. 15 2.3 Research ............................................................................................................................... 18 2.4 Recording and monitoring ..................................................................................................... 22 2.5 Volunteers ............................................................................................................................. 26 2.6 Public access management ................................................................................................. -

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper 1 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper Contents 1. Introduction 2. Aims of this paper 3. Policy Context 4. The role, function and vitality of Identified Retail Centres 5. Survey Areas 6. Hierarchy of BBNPA Centres 7. Town centre Retail Health and Vitality 8. Accommodating Growth in retail 9. Accessibility 10. Visitors Survey 11. Place Plans and Retail Centres 12. Conclusions 13. References 2 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper 1. Introduction Purpose of the document Welsh Government’s Local Development Plan Manual Edition 2 (2015) states the following: ‘Section 69 of the 2004 Act requires a Local Planning Authority to undertake a review of an LDP and report to the Welsh Government at such times as prescribed. To ensure that there is a regular and comprehensive assessment of whether plans remain up-to-date or whether changes are needed an authority should commence a S69 full review of its LDP at intervals not longer than every 4 years from initial adoption and then from the date of the last adoption following a review under S69 (Regulation 41). A plan review should draw upon published AMRs, evidence gathered through updated survey evidence and pertinent contextual indicators, including relevant changes to national policy’. This document has been prepared to provide an evidence base and to examine retail in the Brecon Beacons National Park’s retail centres to inform policy for the replacement Local Development Plan. Evidence gathering information on past and existing circumstances to inform any changes to the retail strategy. This has been done through the analysis of time series data to help identify changes over recent years and any emerging patterns. -

Protecting Wildlife for the Future V

Annual 2014/15 Review Protecting Wildlife for the Future v Contents The Wildlife Trusts 4 What We Do 6 Where We Work 7 From our Chair & CEO 8 People & Nature: our impact 10 Living Landscapes: our impact 12 Living Seas: our impact 14 Highlights around the UK 16 Financial and Organisational Information 20 Our Partners & Biodiversity Benchmark 21 Find your Wildlife Trust 22 My Wild Life stories 23 The statistics in this Annual Review cover the period April 1 2014 - March 31 2015. Elm trees at Holy Vale - a damp The projects and work covered here broadly run from Spring 2014 to Summer 2015. and wild wooded valley with a To download a pdf version go to wildlifetrusts.org/annualreview To order a paper copy please contact [email protected] fabulous nature trail to explore. Holy Vale is looked after by the The Wildlife Trusts. Registered Charity No 207238. Cover photo: Children exploring Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust. peatland habitats at Astley Moss, Lancashire v The Wildlife Trusts Nature makes Wherever you are there is a life possible, it Wildlife Trust caring for wildlife also makes life worth living. and wild places near you. It gives us food, clean water and fresh air, shields us from the elements, and gives us joy, We reach millions of people, inspiring them to value wellbeing and wonder. The Wildlife wildlife and encouraging them to take action for it. Trusts want to help nature recover from the decline that for decades Together, we have a mission to create Living has been the staple diet of scientific studies and news stories. -

Great Places to See Woodland Butterflies a Guide to Some of the UK’S Great Woodland Butterfly Reserves

Great places to see Woodland Butterflies A guide to some of the UK’s great woodland butterfly reserves Protecting Wildlife for the Future Cover: Purple emperor (c) Keith Warmington 40 great places to see... Woodland 23 24 6 38 butterfliesThe UK supports 56 resident species of butterfly, many Of the fritillary species, several have particular plant 9 8 2 of which thrive in woodland habitats. Sunny glades, rides requirements for their caterpillars. Heath fritillary prefers 12 and woodland edges are some of the best places to look cow-wheat; itself an uncommon plant. Violets attract 35 17 for a variety of species, and locating the larval foodplant pearl-bordered, silver-washed, dark green and high 25 of specialist butterflies can make searching that bit easier. brown, and marsh fritillary requires devil’s-bit scabious. 18 Look to the skies for canopy-dwelling butterflies like Bramble patches are also good watchpoints for 10 5 40 purple emperor and purple hairstreak, both of which passing white admiral which are partial to the blossoms, 39 14 26 33 rarely come to nectar. Scan the tops of oak woodlands and any clear areas are good places to look for territorial 19 29 30 15 22 32 with binoculars for the best chance to spot them in flight. battles between speckled wood rivals. 1 34 16 27 13 Most other hairstreaks favour scrubby areas and shrub Here we recommend just a handful of good Wildlife 11 7 21 36 20 plants on which to lay their eggs. Seek out blackthorn for Trust nature reserves to visit for a glimpse of some of the 3 28 31 black and brown hairstreaks and gorse or bilberry for UK’s forest-dwelling butterflies. -

Traditional Orchard Habitat Inventory of Wales

Title of Report (limit to 10 words) Subtitle of Report Like This Do Not Use Full Caps Traditional Orchard Habitat Inventory of Wales Natural Resources Wales Commissioned Report A report for Countryside Council for Wales by the People’s Trust for Endangered Species. Funding from Esmée Fairbairn. Our purpose is to ensure that the natural resources of Wales are sustainably maintained, enhanced and used, both now and in the future Further copies of this report are available from: Published by: Natural Resources Wales [email protected] Ty Cambria [email protected] 29 Newport Road Cardiff CF24 0TP Tel: 01248 387281 0300 065 3000 (general enquiries) [email protected] www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk © Natural Resources Wales. All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of Natural Resources Wales Further information This report should be cited as: Oram, S., Alexander, L. & Sadler, E. 2013. Traditional Orchard Habitat Inventory of Wales: Natural Resources Wales Commissioned. CCW Policy Research Report No. 13/4. NRW Project Supervisor – Hilary Miller, Senior Land Use and Management Advisor , Natural Resources Wales, Maes-y-Ffynnon, Penrhosgarnedd, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2DW. [email protected] This report can be downloaded from the Natural Resources Wales website: http://naturalresourceswales.gov.uk For further information about the project, the methodology used, or the Traditional Orchard habitat please contact PTES. Foreword Commercially driven agricultural advances during the 20th Century led to intensified food-production practices, fruit-growing among them and, as with meadows, woodland management, grazing pasture and the oceans, these modern methods have led directly or indirectly to a dramatic reduction in habitat biodiversity.