330 Included in the Figure. No Spines, However, Appear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X35 X37 Falkirk – Glasgow Serving: Bonnybridge Kilsyth (X35) Cumbernauld (X37) Condorrat Muirhead

X35 X37 Falkirk – Glasgow Serving: Bonnybridge Kilsyth (X35) Cumbernauld (X37) Condorrat Muirhead Bus times from 21 October 2019 The City Chambers at George Square, Glasgow How was your journey? Take two minutes to tell us how you feel... tellfirstbus.com Welcome aboard! Operating many bus routes throughout Central Scotland and West Lothian that are designed to make your journey as simple as possible. Thank you for choosing to travel with First. • Route Page 8-9 • Timetables Pages 4-7, 11-14 • Customer services Back Page What’s changed?: Revised timetable, daily. Value for money! Here are some of the ways we can save you money and speed up your journey: FirstDay – enjoy unlimited journeys all day in your chosen zone. FirstWeek – enjoy unlimited journeys all week in your chosen zone. Contactless – seamless payment to speed up journey times. First Bus App – purchase and store tickets on your mobile phone with our free app. Plan your journey in advance and track your next bus. 3+ Zone – travel all week throughout our network for £25 with our 3+ Zone Weekly Ticket. Find out more at firstscotlandeast.com Correct at the time of printing. Cover image: Visit Scotland / Kenny Lam GET A DOWNLOAD OF THIS. NEW Download t he ne w Firs t B us App t o plan EASY journey s an d bu y t ic kets all in one pla ce. APP TEC H T HE BUS W ITH LESS F USS Falkirk – Condorrat – Glasgow X35 X37 via Bonnybridge, Cumbernauld (X37), Kilsyth (X35) and Muirhead Mondays to Fridays Service Number X37 X35 X37 X35 X37 X35 X37 X35 X37 X35 X35 X37 X35 X37 X35 X37 Falkirk, Central -

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- A02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- a02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE Subject: COMMUNITY GRANTS SCHEME GRANTS TO PLAYSCHEMES - SUMMER 2001 JMcG/ Date: 12 SEPTEMBER 2001 Ref: BP/MF 1. PURPOSE 1.1 At its meeting of 15 May 2001 the community services (community development) sub committee agreed to fund playschemes operating during the summer period and in doing so agreed to apply the funding formula adopted in earlier years. The committee requested that details of the awards be reported to a future meeting. Accordingly these are set out in the appendix. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the committee: (i) note the contents of the appendix detailing grant awards to playschemes which operated during the summer 2001 holiday period. Community Grants Scheme - Playschemes 2001/2002 Playschemes Operating during Summer 2001 Loma McMeekin PSOl/O2 - 001 Bellshill Out of School Service Bellshill & surrounding area 10 70 f588.00 YMCA Orbiston Centre YMCA Orbiston Centre Liberty Road Liberty Road Bellshill Bellshill MU 2EU MM 2EU ~~ PS01/02 - 003 Cambusnethan Churches Holiday Club Irene Anderson Belhaven, Stewarton, 170 567.20 Cambusnethan North Church 45 Ryde Road Cambusnethan, Coltness, Kirk Road Wishaw Newmains Cambusnethan ML2 7DX Cambusnethan Old & Morningside Parish Church Greenhead Road Cambusnethan Mr. Mohammad Saleem PSO 1/02 - 004 Ethnic Junior Group North Lanarkshire 200 6 f77.28 Taylor High School 1 Cotton Vale Carfin Street Dalziel Park New Stevenston Motherwell. MLl 5NL PSO1102-006 Flowerhill Parish Church/Holiday -

SMC-NLS-001: Planning and Architecture Division Assessment

Directorate for Local Government and Communities Planning and Architecture Division (PAD) Assessment Report Case reference SMC-NLS-001 Application details Raising ground level, establishing parking and gardens over scheduled area Site address Antonine Wall, B802 to N of Cuilmuir View, Croy (SM 7639) Applicant Modern Homes Scotland Limited Determining Authority Historic Environment Scotland (HES) Local Authority Area North Lanarkshire Council Reason(s) for notification Notification Direction 2015 – works to be granted Scheduled Monument Consent by Historic Environment Scotland go beyond the minimum level of intervention that is consistent with conserving what is culturally significant in a monument Representations Nil Date notified to Ministers 16 June 2020 Date of recommendation 30 July 2020 Decision / recommendation Clear Description of Proposal and Site: Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) is sought for raising the ground level and creating parking areas and gardens as part of a brownfield housing development sited over part of the line of the Antonine Wall, immediately to the east of Nethercroy Road, north of Constarry Road at Croy. The monument comprises the remains of a section of the Antonine Wall which runs westward from the B802 Kilsyth Road at Croy, across an area of former industrial land and up the slope towards the open ground of Croy Hill. It consists of the rampart, the ditch, the berm (area between rampart and ditch), the upcast mound and the military roadway. The scheduled area measures a maximum of 382m west-east by a maximum of I00m north-south, including the Antonine Wall rampart, berm, ditch, upcast mound, military way and an area to the north and south where traces of activities associated with the construction and use of the monument may survive (see Figure 1). -

Castlecary, Cumbernauld

North Lanarkshire Council Castlecary Road, Castlecary, Cumbernauld (Temporary Closure) Order 2011 On 2 March 2011 the North Lanarkshire Council made the above-named Order under Section 14(1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended by Schedule 1 of the Road Traffic (Temporary Restrictions) Act 1991, and in exercise of all other enabling powers, which makes it unlawful for any person to drive or cause or permit to be driven any motor vehicle (with the exception of vehicles engaged on bridge works and road realigning in association with the M80 Upgrade) on Castlecary Road, Castlecary, Cumbernauld from the extended line of the eastern kerb of the Strathclyde Homes Access Road north eastwards to the boundary with Falkirk Council, a distance of 63 metres or thereby, by reason of works being executed on or near that location. Alternative routes: Vehicles on the south west side of the closure wishing to access the north east side of the closure should proceed south westwards on Castlecary Road, westwards and southwards on A80 Old Inns northbound on-slip road, north eastwards and northwards on A80, northwards and southwards on A80 northbound off-slip road to Haggs, eastwards on A803 Kilsyth Road, north eastwards on A803 Glasgow Road, north eastwards on A803 Bonnybridge Road, eastwards on A803 High Street, southwards on B816 Bridge Street and south westwards on Seabegs Road to the north east side of the closure. Vehicles on the north east side of the closure wishing to access the south west side of the closure should proceed north eastwards on Seabegs Road, northwards on B816 Bridge Street, westwards on A803 High Street, south westwards on A803 Bonnybridge Road, south westwards on A803 Glasgow Road, south westwards on A803 Kilsyth Road, northwards and southwards on A80 south bound on-slip road from Haggs, southwards and south westwards on A80, south westwards on A80 Old Inns southbound off-slip road, northwards on A8011 Wilderness Brae and north eastwards on Castlecary Road to the south east side of the closure. -

AP?!DA ITEM No I..- .__1___

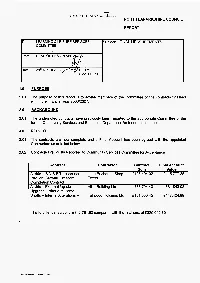

c AP?!DA ITEM No I..-_.__1___..- . NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: LEARNING & LEISURE SERVICES Subject: FINAL MEASUREMENTS COMMITTEE From: HEAD OF DESIGN S Date: 28"' August 2007 /Rev IJF/TM/ CMAD00051 1 .o PURPOSE 1.01 The purpose of this report is to advise members of the Committee of the contracts finalised within the financial year 2006/2007. 2.0 BACKGROUND 2.01 The undernoted contracts have previously been reported to the appropriate Committee of the former Community Services and Education Department for tender acceptance. 3.0 REPORT 3.01 The contracts are now complete and a Final Account has been agreed with the appointed Contractors as detailed below: 3.02 Contracts Previouslv Reported to Communitv Services Committee for Acceptance Contract Contractor Contract Final Account Sum Value Airdrie - B.N.S.F Thrashbush John Buchanan Shop f 125,494.02 f115,777.38 Pavilion, Crowhill Crescent, Fitters Completion Contract Airdrie - External faGade Ailsa Building Ltd f65,704.43 f61,843.03 Upgrade - Airdrie at Home Shotts - Internal Alterations - Fullwood Holdings Ltd f 151,583.45 f147,424.89 The total tender value is f342,781.90compared with the final cost of f325,045.30. \... 2 Report on Final Measurements Continued 3.03 Contracts Previously Reported to Education Committee for Acceptance Contract Contractor Contract Sum Cumbernauld - Baird Kier Scotland f2,849,699.65 f2,915,616.38 Memorial Primary School - Replacement Works Cumbernauld - St Maurice’s Ogilvie Construction f1,595,062.65 f 1,579,127.66 High School - Fire Damage Reinstatement Airdrie - Chapelside Primary JP McFadyen f180,778.50 f167,965.29 School -Window (Commercial Replacement Contracts) Ltd Airdrie - St Margaret’s High JP McFadyen f171,858.42 f166,993.76 School -Window (Commercial Replacement Phase 3 Contracts) Ltd Bellshill - Noble Primary JP McFadyen f151,850.25 f159,499.49 School (Partial) Window (Commercial Replacement Contracts) Ltd Chryston - Chryston Primary Century 21 f103,389.30 f103,761.50 School -Window Replacement Windows Replacment Co. -

CONTACT LIST.Xlsx

Valuation Appeal Hearing: 27th May 2020 Contact list Property ID ST A Street Locality Description Appealed NAV Appealed RV Agent Name Appellant Name Contact Contact Number No. 24 HILL STREET CALDERCRUIX SELF CATERING UNIT £1,400 £1,400 DEIRDRE ALLISON DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 56 WEST BENHAR ROAD HARTHILL HALL £18,000 £18,000 EASTFIELD COMMUNITY ACTION GROUP DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 1 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE WORKSHOP £44,000 £44,000 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 2 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE STORE £80,500 £80,500 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BLDG 4 PART CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE OFFICE £41,750 £41,750 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE OFFICE £24,000 £24,000 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 7 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE WORKSHOP £8,700 £8,700 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 1 GREENHILL COUNTRY ESTATE GREENHILL HOUSE GOLF DRIVING RANGE £5,400 £5,400 GREENHILL GOLF CO CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 CLIFTONHILL SERVICE STN 231 MAIN STREET COATBRIDGE SERVICE STATION £41,000 £41,000 GROVE GARAGES INVESTMENTS LIMITED ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 UNIT B3 1 REEMA ROAD BELLSHILL OFFICE £17,900 £17,900 IN-SITE PROPERTY SOLUTIONS LIMITED DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 UNIT B2 1 REEMA ROAD BELLSHILL OFFICE £18,600 £18,600 IN-SITE PROPERTY SOLUTIONS LIMITED DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 2509 01 & 2509 02 42 CUMBERNAULD ROAD STEPPS ADVERTISING STATION £3,600 £3,600 J C DECAUX CHRISTINE MAXWELL -

Notice of Situation of Polling Places (Cumbernauld and Kilsyth)

SCOTTISH PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION THURSDAY, 6 MAY 2021 CUMBERNAULD AND KILSYTH CONSTITUENCY Notice of Situation of Polling Places PO/ Polling Station No. of Ballot District Polling Place Part of Register No. Voters Box No. Reference 1 NL1 St. Patrick’s Primary School 1 Voters in streets etc commencing with Adams 462 Backbrae Street Place to Howe Road inclusive Kilsyth G65 0NA 2 NL1 St. Patrick’s Primary School 2 Voters in streets etc commencing with Jarvie 472 Backbrae Street Crescent to William Street inclusive and other Kilsyth G65 0NA electors 3 NL2 Holy Cross Primary School 1 Voters in streets etc commencing with 809 Main Street Auchinstarry to Weldon Place inclusive and Croy G65 9JG other electors 4 NL3 Kilsyth Academy 1 Voters in streets etc commencing with 822 Balmalloch Abercrombie Place to Bar Hill Place inclusive Kilsyth G65 9NF 5 NL3 Kilsyth Academy 2 Voters in streets etc commencing with Belmont 756 Balmalloch Street to John Wilson Drive inclusive Kilsyth G65 9NF 6 NL3 Kilsyth Academy 3 Voters in streets etc commencing with Kelvin 811 Balmalloch Way to Parkfoot Street inclusive Kilsyth G65 9NF 7 NL3 Kilsyth Academy 4 Voters in streets etc commencing with Rennie 799 Balmalloch Road to Westfield Road inclusive and other Kilsyth G65 9NF electors 8 NL4 Chapelgreen Primary School 1 Voters in streets etc commencing with Anderson 426 Mill Road Crescent to Whin Loan inclusive and other Queenzieburn G65 9EF electors 9 NL5 Kilsyth Primary School 1 Voters in streets etc commencing with 729 Shuttle Street Allanfauld Road to Craigstone View -

Health and Social Care Locality Profile September 2016

North Health and Social Care Locality Profile September 2016 Reproduced by permission of the, Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2016. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100023396. 1 Contents 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.0 Context and Geographical Area .................................................................................................. 5 3.0 Local Services ............................................................................................................................ 14 4.0 Community Assets .................................................................................................................... 16 5.0 Needs Assessment Data ............................................................................................................ 16 6.0 Priority areas for Action ............................................................................................................ 42 Appendix 1: Map of Care homes in North Lanarkshire (June 2016) ................................................. 44 Appendix 2: Community Assets – North Locality .............................................................................. 45 Appendix 3 – Locality profiling data.................................................................................................. 47 Appendix 4: Number (%) of Ethnic Groups in North H&SCP/Locality .............................................. -

6 Landscape and Visual

Heathland Wind Farm Chapter 6 EIA Report Landscape and Visual 6 LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL 6.1 INTRODUCTION This Chapter of the Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIA Report) evaluates the effects of the Development on the landscape and visual resource. The Development (up to 14 turbines at up to 180m to tip) represents a revised proposal to that of the consented Heathland Wind Farm (17 turbines at 132m to tip). A comparison between the effects identified for the consented scheme and Development assessed here is provided in the Planning Statement. This assessment was undertaken by LUC on behalf of Arcus Consultancy Services Limited (Arcus). This Chapter of the EIA Report is supported by the following Technical Appendix documents provided in Volume 3 Technical Appendices: Appendix A6.1 – Landscape and Visual Assessment Methodology; Appendix A6.2 – Visualisation Methodology; Appendix A6.3 – Residential Visual Amenity Assessment; and Appendix A6.4 – Aviation Lighting Assessment. This chapter includes the following elements: Legislation, Policy and Guidance; Consultation; Assessment Methodology and Significance Criteria; Landscape Baseline Conditions; Visual Baseline Conditions; Assessment of Potential Effects; Mitigation and Residual Effects; Cumulative Effect Assessment; Summary of Effects; Statement of Significance; and Glossary. Volume 2 of the EIA Report contains the EIA Report Figures. This chapter is supported by Volume 2b LVIA Figures and Volume 2c LVIA Visualisations. 6.2 LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE The following -

Gluten Free Pharmacies

Contractor code Business Name Address 1 Address 2 Town Post Code Work Phone Fax Number 3007 Boots Chemist 19 Graham Street Airdrie ML6 6DD 01236 762105 01236 761169 3008 Boots Chemist 94 Main Street Coatbridge ML5 3BQ 01236 423756 01236 700092 3009 Boots Chemist Unit 24 Antonine Centre Cumbernauld G67 1JW 01236 737752 01236 721933 3010 Boots Chemist 33/37 The Plaza East Kilbride G74 1LW 01355 228771 01355 228771 3011 Boots Chemist 44 Regent Way Hamilton ML3 7DZ 01698 283475 / 477563 01698 421338 3012 Boots Chemist 85/87 High Street Lanark ML11 7LN 01555 663176 01555 660691 3013 Boots Chemist 47/49 Brandon Parade Motherwell ML1 1RE 01698 261411 01698 230534 3014 Boots Chemist 45 Main Street Uddingston G71 7EP 01698 813842 01698 816405 3030 Dickson Chemist 654 Old Edinburgh Road Viewpark Uddingston G71 6HQ 01698 818164 01698 810300 3055 D Charteris 57 Main Street Kilsyth G65 0AH 01236 822177 01236 822177 3057 Greenhills Pharmacy 7 Greenhills Square Greenhills East Kilbride G75 8TT 01355 235450 01355 235450 3066 William Y Graham Ltd 8 Market Place Burnhead Street Uddingston G71 5AL 01698 813307 01698 813307 3084 A & I Crawford 19 Shottskirk Road Shotts ML7 4AB 01501 821508 01501 822048 3086 T.McLean & Sons Ltd 2 Clyde Walk Town Centre Cumbernauld G67 1DA 01236 724440 01236 731915 3096 Monklands Pharmacy 108/110 Deedes Street Airdrie ML6 9AF 01236 753252 01236 762728 3108 Health Centre Pharmacy 17 Manse Road Newmains ML2 9AX 01698 384360 01698 381287 3119 J E Robertson 107 Main Street Coatbridge ML5 3EL 01236 423740 01236 423740 3129 Your -

NORTH LANARKSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Proposed Plan Policy Document

NORTH LANARKSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Proposed Plan Policy Document FOREWORD The Local Development Plan sets out the Policies and Proposals to achieve North Lanarkshire’s development needs over the next 5-10 years. North Lanarkshire is already a successful place, making This Local Development Plan has policies identifying a significant contribution to the economy of Scotland the development sites we need for economic growth, but we want to make it even more successful through sites we need to protect and enhance and has a more providing opportunities to deliver new housing for our focussed policy structure which sets out a clear vision for growing population, creating a climate where businesses North Lanarkshire as a PLACE with policies ensuring the can grow and locate and where opportunities for leisure development of sites is appropriate in scale and character and tourism are enhanced. and will benefit our communities and safeguard our environment. We will ensure that the right development happens in the right places, in a way that balances supply and demand We will work with our partners and communities to for land uses, helps places have the infrastructure they deliver this Plan and a more successful future for need without compromising the environment that North Lanarkshire. defines them and makes North Lanarkshire a distinctive and successful place where people want to live, work, visit and invest. Councillor James Coyle Convener of Planning and Transportation Local Development Plan Policy 3 Executive summary The North Lanarkshire Local Development Plan is the land use planning strategy for North Lanarkshire. A strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim. -

The Castlecary Hoard and the Civil War Currency Of

THE CASTLECARY HOARD AND THE CIVIL WAR CURRENCY OF SCOTLAND DONAL BATESON THIS publication of an unrecorded hoard from Castlecary, ending with coins of the 1640s, presents an opportunity to examine the Civil War coin hoards from Scotland and the Scottish currency of the period. The hoard This is an enigmatic hoard in so far as it was recently re-discovered, in the National Museums of Scotland merely with a note saying, 'Castlecary Hoard 1926'. Nothing more is known of the circumstances of its finding or indeed whether it was brought to the then National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in 1926 or subsequently. In any event it appears to have been put to one side and not returned to.1 Castlecary is a small village in Stirlingshire situated to the west of Falkirk.2 The find contains 134 coins, all of silver. The majority are English, issues of the Tower Mint, of Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I. In addition there are three Scottish coins of James VI as well as four of his Irish shillings. It includes no foreign coin. A summary shows: 8 shillings and 36 sixpences of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) 1 half-crown, 10 shillings and 8 sixpences of James I (1603-25) 26 half-crowns, 31 shillings and 7 sixpences of Charles I (1625-49) 2 thistle merks and 1 thirty shillings (Scots) of James VI (1567-1625) 4 Irish shillings of James I The face value of the English, and Irish, coins in the mid-seventeenth century was £7 6 s Od.