Thomas M. Clifton House 1423 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Ball and Trap Shooting

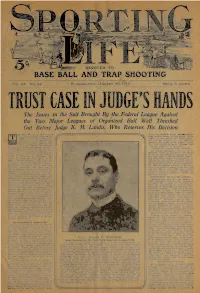

BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 22 PHILADELPHIA. JANUARY 3O, 1915 PRICE 5 CENTS TRUST CASE IN JUDGE'S HANDS The Issues in the Suit Brought By the Federal League Against the* Two Major Leagues of Organized Ball Well Threshed Out Before Judge K. M. Landis, Who Reserves His Decision . j-lHE Base Ball Trust Suit came to which was intended mainly for VM against I ^ "* I trial before Judge Kenesaw M. those enemies operating from within, though I I I Lapdis, in the United States Dis it was used also against the Federal League; trict Court, at Chicago, January the third was found in the rules regarding 20, with a host of lawyers, mag- contracts; the fourth in the alleged "black 5^ nates, and base ball notables of var list,'* and the fifth styling as "outlaws" and ious degree, present. The members "contract jumpers" its opponents. of the National Commission, Messrs. Herrmann, Johnson and Tener, were present, flanked by EXCESSIVE COMMISSION POWER counsel, which included George Wharion 1'ep- The National Agreement's rule that it is in per and Samuel L. Clement, of Philadelphia;' dissoluble except by unanimous vote admits .Judge Williams, of New York; attorneys of but one fair deduction, acording to Addi- Oalvinum v 111 andiuiu. -Kinkead,r\. - (ii i\cuu, ' ofVL- ' Cincinnati;v/i*i^iuiiaii<" ' of Chi-and«u» soii, first, that it provides against competi George W. Miller itnd John Healy, of Chi tion from within; second, that players may bo cago. President Gilmore, R. B. Ward an<l held as they come and go, and third", that the William K. -

Arkansas Airwaves

Arkansas Airwaves Ray Poindexter A little more than a year after radio broadcasting was first heard nationally, Arkansas' first regular licensed station went on the air. The state's progress has not usually been as rapid in most other fields. At first, radio was considered to be a novelty. There was no advertising revenue to support it. Many of the early Arkansas stations left the air. Those that remained were jolted by the Great Depression. By the time things started getting better economic- ally, the nation became involved in World War ll. It brought various broadcasting restrictions and a shortage of products to be advertised. Radio's economic heyday in Arkansas came after the war. New stations began to spring up in many towns in the state. Soon the rushing radio surge was met head-on by a new and threatening medium --television! The question of survival was uppermost in the minds of some radio station owners. In order to live with the new force that had a picture as well as sound, many Arkansas stations had to make necessary adjust- ments. Today, both radio and television are alive and well in Arkansas. Jacket design by George Fisher -sd: `a, 1110 CG 2i7net, ARKANSAS AIRWAVES by Ray Poindexter I Copyright © 1974 Ray Poindexter North Little Rock, Arkansas II The richest man cannot buy what the poorest man gets free by radio. - from an early RCA ad III Photograph courtesies as follows: WOK-Mrs. Pratt Remmel and Arkansas Power & Light Co. KFKQ-Faulkner County Historical Society KUOA-Lester Harlow KTHS-Patrick C. -

Sandwiching in History Nannie C. Wright House 1617 S. Battery Street, Little Rock April 1, 2016 by Rachel Silva

1 Sandwiching in History Nannie C. Wright House 1617 S. Battery Street, Little Rock April 1, 2016 By Rachel Silva Intro Good afternoon, my name is Rachel Silva, and I work for the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. **Before we get started, Carol Young from the Quapaw Quarter Association will tell you about the upcoming Spring Tour of Homes in Hillcrest May 7-8. Thank you for coming, and welcome to the “Sandwiching in History” tour of the Nannie Wright House. I’d like to thank John Steel and Whitney Patterson Steel for allowing us to tour their beautiful home! This tour is worth one hour of HSW continuing education credit through the American Institute of Architects. Please see me after the tour if you’re interested. Located in the Central High School Neighborhood Historic District (National Register-listed 8/16/1996), the Nannie C. Wright House was built about 1909. The house is an American Foursquare with an eclectic mix of architectural details. 2 Central High Neighborhood/Centennial Addition Historically, Little Rock’s Central High School neighborhood was called the West End because the area was literally at the western edge of the city. Platted in 1877, the Centennial Addition was the largest addition in the neighborhood. It was so named to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (1776-1876). Only a few scattered homes existed in the West End until the mid-to-late 1890s, when significant construction began. However, Little Rock residents were enticed to visit the West End beginning on May 16, 1885, when the Little Rock Street Railway Company opened West End Park at the end of the streetcar line. -

Negro League Ball Parks

Negro League Ball Parks The following list of Negro League teams and the ball parks they played in is by no means considered complete. Some parks listed may have hosted as few as one home game for the team listed. Team City Ball Park Abrams Giants Indianapolis, IN Brighton Beach Park Akron Black Tyrites Akron, OH League Park (1933) Akron Grays Akron , OH League Park (1933) Albany Giants Albany, GA Southside Ball Park (1926) Alcoa Aluminum Sluggers Alcoa, TN Alcoa Park (1932) Alexandria Lincoln Giants Alexandria, VA Lincoln Street Park (1933) Algiers Giants Algiers, LA West Side Park (1932-1933) Algona Brownies Algona, IA Fair Grounds (1903) All Nations Kansas City, MO Association Park (1916-1917) Ashville Blues Ashville, NC McCormick Field (1945-1947) Atlanta Athletics Atlanta, GA Ponce de Leon Park (1933) Morris Brown College (1933) Atlanta Black Crackers Atlanta, GA Ponce de Leon Park (1920-1940) Morris Brown Field (1920-1921) Spiller Park (1926-1927 & 1935) Morehouse College (1932) Harper’s Field (1945) Atlanta-Detroit Brown Crackers Atlanta, GA Ponce de Leon Park (1949) Atlanta Brown Crackers Atlanta, GA Ponce de Leon Park (1950) Atlanta Grey Sox Atlanta, GA Spiller Field (1929) Atlanta Panthers Atlanta, GA Ponce de Leon Park (1931) 1 Team City Ball Park Atlantic City Bacharach Giants Atlantic City, NJ Inlet Park (1904-1921) Bacharach Field (1916-1929) Greyhound Park (1928) New York City, NY Dyckman Oval (1920) New York Oval (1922) Bronx Oval (1920’s) Lewisohn Stadium (1920’s) Brooklyn, NY Ebbets Field (1920-1921) Harrison, NJ Harrison -

Base Ball Goods

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 19 PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 9. 1915 PRICE 5 CENTS BASE BALL ATTACKED AS TRUST Beginning of Legal Proceedings for a Star Player By a National League Club Provokes the Federal League Into Attacking Organized Ball in Court as a Trust, Asking for Its Dissolution The Great Issue Reached! Lajoie Sold to Athletics Chicago, lib., January 5. Charg Philadelphia, Pa-., January S. ing the Rational Commission, its Manager Mack, of the 1'hiladclphia laws and the \ationul Agreement Athletics, announced this afternoon under u'hich its members work, arc that he had purchased the famous in violation of the common law and .\apoleon JjU-joie, second bascman the Anti-Trust Late, the Federal of the Cleveland Club, and will play League today filed suit in the him at second base this season in United States District Court of Chi place of Eddie Collins, who icon cago, asking that the Xational Com sold to Chicago. The deal was a mission be decltircl illegal and its straight cash transaction. Manager members enjoined from further Mack paying out a goodly si if c of commission of illegal acts. The suit the money he received for Collins to is to come up before Judge Kene- the Cleveland Club and assuming sau) Mountain F.andis, who, several Lajoie's contract. 31an&ger Mack years ago fined the Standard Oil believes that Lajoie has much good Company $2'J,000,000, on January base ball left in him and mil get it 20. One of the can-sen charged is out of him u-ith Jack Barry and that the contracts arc null and void. -

Ninth Annual Southern Association Baseball Conference Special Guest: Ninth Annual Southern Association Baseball Conference Presenters

2012 Southern Association Conference dedicated to the memory of William “Bill” Ross, III. July 25, 1964 – January 27, 2012 Special thanks to: The Woodward Family Ninth Annual Dr. Johnie Grace and Martin-Grace Benefit Group Triple Play Baseball Club Southern Association Skip Nipper and sulphurdell.com Baseball Conference Liz Rybka March 3RD 2 0 1 2 friends of rickwood ✆ 205.458.8161 or www.rickwood.com Spar Stadium, Ninth Annual home of the Shreveport Sports, Southern Association Baseball Conference Southern Association members Rickwood Field Birmingham, Alabama 1959-1961. rd Courtesy of Saturday, March 3 , 2012 Tony Roberts. Baron teammates Billy Bancroft and Shine Cortazzo, 1930. 9:00 A.M. Morning coffee and donuts Courtesy of Mrs. Billy Bancroft & Chuck Stewart. 9:30 A.M. Welcome and introductory remarks 9:45 A.M. Clarence Watkins “Russwood: The Evolution of a Ballpark” 10:30 A.M. Derby Gisclair Birmingham Black Baron fans gather for game “New Orleans Ballparks” at Rickwood Field, late 1940’s. 11:15 A.M. Morning break – Collector Exhibits Courtesy of Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center. 11:30 A.M. Skip Nipper “The Colorful, Quirky Confines of Nashville’s Sulphur Dell” Night game at Chattanooga’s Engel Stadium, home of the Lookouts. 12:15 P.M. Lunch with Special Guest Paul Seitz Courtesy of Clarence Watkins. Former Birmingham Baron and Shreveport Sport 1:00 P.M. Dan Creed “Chattanooga’s Engel Stadium: Heyday to No Play” Chattanooga Baseball Company letterhead, featuring Engel Stadium. Courtesy of Clarence Watkins. 1:45 P.M. Gary Higgenbotham “Mobile’s Historic Baseball Parks” 2:30 P.M.