HCMP000622/1990 NOTE Judicial Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM)

Appendix Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM) The Honourable Chief Justice CHEUNG Kui-nung, Andrew Chief Justice CHEUNG is awarded GBM in recognition of his dedicated and distinguished public service to the Judiciary and the Hong Kong community, as well as his tremendous contribution to upholding the rule of law. With his outstanding ability, leadership and experience in the operation of the judicial system, he has made significant contribution to leading the Judiciary to move with the times, adjudicating cases in accordance with the law, safeguarding the interests of the Hong Kong community, and maintaining efficient operation of courts and tribunals at all levels. He has also made exemplary efforts in commanding public confidence in the judicial system of Hong Kong. The Honourable CHENG Yeuk-wah, Teresa, GBS, SC, JP Ms CHENG is awarded GBM in recognition of her dedicated and distinguished public service to the Government and the Hong Kong community, particularly in her capacity as the Secretary for Justice since 2018. With her outstanding ability and strong commitment to Hong Kong’s legal profession, Ms CHENG has led the Department of Justice in performing its various functions and provided comprehensive legal advice to the Chief Executive and the Government. She has also made significant contribution to upholding the rule of law, ensuring a fair and effective administration of justice and protecting public interest, as well as promoting the development of Hong Kong as a centre of arbitration services worldwide and consolidating Hong Kong's status as an international legal hub for dispute resolution services. The Honourable CHOW Chung-kong, GBS, JP Over the years, Mr CHOW has served the community with a distinguished record of public service. -

![0908992 [2010] RRTA 389 (14 May 2010)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3036/0908992-2010-rrta-389-14-may-2010-633036.webp)

0908992 [2010] RRTA 389 (14 May 2010)

0908992 [2010] RRTA 389 (14 May 2010) DECISION RECORD RRT CASE NUMBER: 0908992 DIAC REFERENCE(S): CLF2009/112260 CLF2009/98641 COUNTRY OF REFERENCE: Stateless TRIBUNAL MEMBER: Tony Caravella DATE: 14 May 2010 PLACE OF DECISION: Perth DECISION: The Tribunal affirms the decision under review The Tribunal considers that this case should be referred to the Department to be brought to the Minister’s attention for possible Ministerial intervention under section 417 of the Migration Act. STATEMENT OF DECISION AND REASONS APPLICATION FOR REVIEW 1. This is an application for review of a decision made by a delegate of the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship to refuse to grant the applicant a Protection (Class XA) visa under s.65 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act). 2. The applicant claims to be stateless. The applicant claims to have been born in Indonesia and to have lived there from birth to 1967. He claims he then moved to the People’s Republic of China and lived there until 1971 when he claims he moved to the British Overseas Territory of Hong Kong where he lived from 1971 to 1985. The applicant arrived in Australia [in] October 1985 and applied to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (“the Department”) for a Protection (Class XA) visa [in] August 2009. The delegate decided to refuse to grant the visa [in] October 2009 and notified the applicant of the decision and his review rights by letter [on the same date]. 3. The delegate refused the visa application on the basis that the applicant is not a person to whom Australia has protection obligations under the Refugees Convention. -

Hong Kong, China

Part I. Economy Case Studies Session I. Northeast Asia Session: Case Study HONG KONG, CHINA Prof. Wong Siu-lun University of Hong Kong PECC-ABAC Conference on “Demographic Change and International Labor Mobility in the Asia Pacific Region: Implications for Business and Cooperation” in Seoul, Korea on March 25-26, 2008 Hong Kong: Demographic Change and International Labor Mobility Siu-lun WONG ∗ Markéta MOORE ∗∗ James K. CHIN ∗∗∗ PECC-ABAC Conference on Demographic Change and International Labor Mobility in the Asia Pacific Region, Seoul, March 25-26, 2008. ∗ Professor and Director, Centre of Asian Studies, The University of Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] ∗∗ Lecturer, Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] ∗∗∗ Research Assistant Professor, Centre of Asian Studies, The University of Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Hong Kong is a city created by migrants.1 Due to special historical circumstances, it became a crossroad where people and capital converged. Hong Kong has been through many stages in its transformation from a small fishing outpost into the fast-paced metropolis place we find today. Strategically positioned in East Asia, bordering the South China Sea and the Chinese province of Guangdong, it has developed close links with the economies of Southeast Asia, Japan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These links gave rise to Hong Kong’s image as a regional entrepôt and a business gateway to China. The same applied to the migration landscape, in which Hong Kong served as a major conduit for emigration from China. -

CANADIAN IMMIGRATION POLICIES and the MAKING of CHINESE CANADIAN IDENTITY, 1949-1989 by Shawn Deng a THESIS SUBMIT

EBB AND FLOW: CANADIAN IMMIGRATION POLICIES AND THE MAKING OF CHINESE CANADIAN IDENTITY, 1949-1989 by Shawn Deng A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History and Classical Studies) MCGILL UNIVERSITY (Montreal) August 2019 © Shawn Deng, 2019 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the ways in which Canadian immigration policies influenced the making of Chinese Canadian identity between 1949 and 1989, by focusing on three historic moments: the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the family reunification agreement between Canada and the PRC in 1973, and the Tiananmen massacre in 1989. I use these three historic moments to trace a state-community connection, and to show how state-community interaction on Canadian immigration policies shaped the perception of being Chinese in Canada. To clarify this process, my project brings two interrelated yet distinct concepts to bear in tracing the nuances of Chinese identity in Canada. The concept of “diasporic identity” draws attention to the way Chinese communities living abroad define and express their identities by building links between the local settler society and the ancestral homeland. The concept of “Chinese Canadian identity” draws attention to the way the Chinese in Canada developed their sense of belonging in Canada when the Canadian state met their needs in terms of diasporic identity. To these investigative ends, this thesis analyzes the responses of the Canadian state to key historical moments using government documents and parliamentary Hansards, and analyzes the responses of the Chinese in Canada using two Chinese Canadian newspapers: The Chinese Times and the Shing Wah Daily News. -

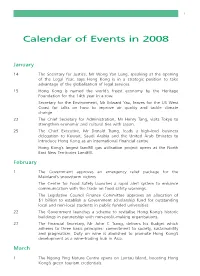

Calendar of Events in 2008

i Calendar of Events in 2008 January 14 The Secretary for Justice, Mr Wong Yan Lung, speaking at the opening of the Legal Year, says Hong Kong is in a strategic position to take advantage of the globalisation of legal services. 15 Hong Kong is named the world’s freest economy by the Heritage Foundation for the 14th year in a row. Secretary for the Environment, Mr Edward Yau, leaves for the US West Coast for talks on how to improve air quality and tackle climate change. 22 The Chief Secretary for Administration, Mr Henry Tang, visits Tokyo to strengthen economic and cultural ties with Japan. 25 The Chief Executive, Mr Donald Tsang, leads a high-level business delegation to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to introduce Hong Kong as an international financial centre. Hong Kong’s largest landfill gas utilisation project opens at the North East New Territories Landfill. February 1 The Government approves an emergency relief package for the Mainland’s snowstorm victims. The Centre for Food Safety launches a rapid alert system to enhance communication with the trade on food safety warnings. The Legislative Council Finance Committee approves an allocation of $1 billion to establish a Government scholarship fund for outstanding local and non-local students in public funded universities. 22 The Government launches a scheme to revitalise Hong Kong’s historic buildings in partnership with non-profit-making organisations. 27 The Financial Secretary, Mr John C Tsang, delivers his Budget which adheres to three basic principles: commitment to society, sustainability and pragmatism. Duty on wine is abolished to promote Hong Kong’s development as a wine-trading hub in Asia. -

China's National Security Law for Hong Kong

China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46473 SUMMARY R46473 China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: August 3, 2020 Issues for Congress Susan V. Lawrence On June 30, 2020, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed a Specialist in Asian Affairs national security law (NSL) for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Hong Kong’s Chief Executive promulgated it in Hong Kong later the same day. The law is widely seen Michael F. Martin as undermining the HKSAR’s once-high degree of autonomy and eroding the rights promised to Specialist in Asian Affairs Hong Kong in the 1984 Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong, an international treaty between the People’s Republic of China (China, or PRC) and the United Kingdom covering the 50 years from 1997 to 2047. The NSL criminalizes four broadly defined categories of offenses: secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and “collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security” in relation to the HKSAR. Persons convicted of violating the NSL can be sentenced to up to life in prison. China’s central government can, at its or the HKSAR’s discretion, exercise jurisdiction over alleged violations of the law and prosecute and adjudicate the cases in mainland China. The law apparently applies to alleged violations committed by anyone, anywhere in the world, including in the United States. The HKSAR and PRC governments have already begun implementing the NSL, including setting up the new entities the law requires. -

Country of Origin Information Report: China October 2003

China, Country Information Page 1 of 148 CHINA COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS: OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: GLOSSARIES ANNEX E: CHECKLIST OF CHINA INFORMATION PRODUCED BY CIPU ANNEX F: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1. This report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2. The report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3. The report is referenced throughout. It is intended for use by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. http://www.ind.homeoffice.gov.uk/ppage.asp?section=168&title=China%2C%20Country%20Information 11/17/2003 China, Country Information Page 2 of 148 1.4. It is intended to revise the reports on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

GN 566 Immigration Department It Is Hereby Notified That Sealed Tender in Triplicate Is Invited for the Following

G.N. 566 Immigration Department It is hereby notified that sealed tender in triplicate is invited for the following:— Closing Date Tender Reference Subject and Time IMMD/PT/12/2020 Supply of Barcode Scanners to the Immigration 15.3.2021 Department (12.00 noon) Forms of tender are obtainable from:— (i) The Supplies Sub-division, Immigration Department, Room 3415, 34th Floor, Immigration Tower, 7 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong (Tel.: 2829 3589, Fax: 2802 7080); (ii) The Central and Western Home Affairs Enquiry Centre, Ground Floor, Harbour Building, 38 Pier Road, Central, Hong Kong (Tel.: 2189 2819); and (iii) The Yau Tsim Mong Home Affairs Enquiry Centre, Mong Kok Government Offices, Ground Floor, 30 Luen Wan Street, Kowloon (Tel.: 2399 2111). Further particulars in connection with the tender are obtainable from:— The Supplies Sub-division, Immigration Department, Room 3415, 34th Floor, Immigration Tower, 7 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong (Tel. No.: 2829 3587, Fax No.: 2802 7080). Tenders must be clearly marked with the tender reference and the subject of the tender on the outside of the envelope (but should not bear any indication which may relate the tender to the tenderer) addressed to the Chairman, Tender Opening Committee, Government Logistics Department, and placed in the Government Logistics Department Tender Box situated at the Ground Floor, North Point Government Offices, 333 Java Road, North Point, Hong Kong before 12.00 noon (Hong Kong Time) on the closing date of the tender as stated above. Tenders must be deposited in the tender box as specified in this tender notice (‘Specified Tender Box’) before the tender closing time. -

Action Plan to Tackle Trafficking in Persons and to Enhance Protection

Action Plan to Tackle Trafficking in Persons and to Enhance Protection of Foreign Domestic Helpers in Hong Kong March 2018 CONTENTS Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 2 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6 Overall Strategy .......................................................................................................... 10 Victim Identification, Investigation, Enforcement and Prosecution .................... 13 Victim Protection and Support ................................................................................. 16 Prevention .................................................................................................................... 19 Partnership ................................................................................................................... 21 Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 23 1 FOREWORD Trafficking in Persons (TIP) is a heinous crime which is not tolerated in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government has always been fully committed to combatting TIP through multi-faceted measures. As the potential threats of trafficking posed by transnational organised -

Immigration Department 年報annual Report

我們的理想 Our Vision 我們要成為世界上以能幹和效率稱冠的入境事務隊伍。 We will be the foremost immigration service in the world in effectiveness and efficiency. The Design Associates 入境事務處 2009/10 Immigration Department 年報 Annual Report 我們的理想 Our Vision 我們要成為世界上以能幹和效率稱冠的入境事務隊伍。 We will be the foremost immigration service in the world in effectiveness and efficiency. The Design Associates 入境事務處 2009/10 Immigration Department 年報 Annual Report 我們的信念 Our Values 我們的使命 Our Mission 正直誠信、公正無私 Integrity and Impartiality 我們要全力執行下列工作,為香港的安定繁榮作出 We will contribute to the security and prosperity of 我們要以公正無私和誠實的態度,忠誠地執行本處的各 We will faithfully apply our policies and practices with 貢獻: Hong Kong by: 項政策和工作,並時刻維持本處高度正直誠信的標準。 impartiality and honesty and will uphold our high standards of integrity at all times. ■ 執行有效的出入境管制 ■ exercising effective immigration control ■ facilitating the visit of genuine travellers ■ 方便旅客訪港 以禮待人、體恤市民 Courtesy and Compassion ■ keeping out undesirables ■ 拒絕讓不受歡迎人物入境 ■ preventing and detecting immigration-related crimes 我們要尊重每位市民,對每位市民誠懇有禮和體恤關 We will treat each member of the public with respect, ■ issuing to residents highly secure identity cards and 懷。我們要設身處地去了解不同的觀點和看法,並且彈 consideration, courtesy and compassion. We will be ■ 防止及偵查與出入境事宜有關的罪行 travel documents 性地實施各項政策,以切合特別的需求。 empathetic, appreciative of different perspectives and ■ 為居民簽發高度防偽的身份證及旅行證件 ■ providing efficient civil registration services for births, flexible in the application of policies to meet specific The Design Associates ■ 提供高效率的出生、死亡及婚姻登記服務 deaths and marriages needs. 我們要按一視同仁的原則,為市民提供優質服務,並以 -

When a Wife Is a Visitor: Mainland Chinese Marriage Migration, Citizenship, and Activism in Hong Kong

WHEN A WIFE IS A VISITOR: MAINLAND CHINESE MARRIAGE MIGRATION, CITIZENSHIP, AND ACTIVISM IN HONG KONG by Melody Li Ornellas Bachelor of Social Science (1st Hons.), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2000 Master of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Melody Li Ornellas It was defended on April 21, 2014 and approved by Robert M. Hayden, Professor, Department of Anthropology Evelyn Rawski, Professor, Department of History Gabriella Lukacs, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology Dissertation Director: Nicole Constable, Professor, Department of Anthropology ii Copyright © by Melody Li Ornellas 2014 iii WHEN A WIFE IS A VISITOR: MAINLAND CHINESE MARRIAGE MIGRATION, CITIZENSHIP, AND ACTIVISM IN HONG KONG Melody Li Ornellas, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This dissertation investigates contemporary Hong Kong-China cross-border marriages. In particular, it focuses on the family life and the complexity of politics, power, and agency in mainland Chinese migrant wives’ individual and collective experiences of rights and belonging in Hong Kong. The women in question are allowed to live temporarily in Hong Kong as “visitors” by utilizing family visit permits which must be periodically renewed in mainland China. -

S for S and Heads of Six Disciplined Services Departments Support

S for S welcomes and supports decision of NPC on improving electoral system of HKSAR ********************************************************** The Decision of the National People's Congress (NPC) on improving the electoral system of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) was adopted at the fourth session of the 13th NPC today (March 11), implementing the "patriots administering Hong Kong" principle. The Secretary for Security, Mr John Lee, welcomes and fully supports the NPC's Decision. He will lead the disciplinary forces to fully co-operate and continue to fulfil resolutely the responsibility of safeguarding national sovereignty, security and development interests, and ensuring the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong. Mr Lee said that frequent chaotic scenes were witnessed in the Legislative Council (LegCo) for quite some time, including some LegCo members blatantly advocating "Hong Kong independence" during oath-taking. In particular since 2019 when violent riots emerged in society, some LegCo members impeded the operation of the LegCo on purpose and obstructed LegCo staff in their execution of duties; some supported violence, called rioters "brothers in arms", colluded with foreign forces, begged foreign countries for sanctioning against Hong Kong and acted as foreign proxies; and some even associated with subversive forces with an intention of bringing "mutual destruction" to Hong Kong, and sabotaged the governance of the HKSAR Government, with a view to compelling the Central People's Government and the HKSAR Government. These people wanted Hong Kong to jump off a cliff with them and pushed Hong Kong people into the abyss. Such attempts have severely undermined Hong Kong's safety, order and stability, violating the Basic Law and the Law of the People's Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (National Security Law) as well as relevant Hong Kong laws.