DOCUMENT RESUME Symposium. Proceedings (Durham, New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Southeast Region

VT Dept. of Forests, Parks and Recreation Mud Season Trail Status List is updated weekly. Please visit www.trailfinder.info for more information. Southeast Region Trail Name Parcel Trail Status Bear Hill Trail Allis State Park Closed Amity Pond Trail Amity Pond Natural Area Closed Echo Lake Vista Trail Camp Plymouth State Park Caution Curtis Hollow Road Coolidge State Forest (east) Open Slack Hill Trail Coolidge State Park Closed CCC Trail Coolidge State Park Closed Myron Dutton Trail Dutton Pines State Park Open Sunset Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Broad Brook Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Sunrise Trail Fort Dummer State Park Open Kent Brook Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed Appalachian Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed Old Growth Interpretive Trail Gifford Woods State Park Closed West River Trail Jamaica State Park Open Overlook Trail Jamaica State Park Closed Hamilton Falls Trail Jamaica State Park Closed Lowell Lake Trail Lowell Lake State Park Closed Gated Road Molly Beattie State Forest Closed Mt. Olga Trail Molly Stark State Park Closed Weathersfield Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Windsor Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Futures Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Mt. Ascutney Parkway Mt. Ascutney State Park Open Brownsville Trail Mt. Ascutney State Park Closed Gated Roads Muckross State Park Open Healdville Trail Okemo State Forest Closed Government Road Okemo State Forest Closed Mountain Road Okemo State Forest Closed Gated Roads Proctor Piper State Forest Open Quechee Gorge Trail Quechee Gorge State Park Caution VINS Nature Center Trail Quechee Gorge State Park Open Park Roads Silver Lake State Park Open Sweet Pond Trail Sweet Pond State Park Open Thetford Academy Trail Thetford Hill State Park Closed Gated Roads Thetford Hill State Park Open Bald Mt. -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in Vermont 2015

FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT 2015 AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION MONTPELIER - VERMONT 05620-3801 STATE OF VERMONT PETER SHUMLIN, GOVERNOR AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEBORAH L. MARKOWITZ, SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION Michael C. Snyder, Commissioner Steven J. Sinclair, Director of Forests http://www.vtfpr.org/ We gratefully acknowledge the financial and technical support provided by the USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry that enables us to conduct the surveys and publish the results in this report. This document serves as the final report for fulfillment of the Cooperative Lands – Survey and Technical Assistance and Forest Health Monitoring programs. In accordance with federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. This document is available upon request in large print, Braille or audio cassette. FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT CALENDAR YEAR 2015 PREPARED BY: Barbara Schultz, Trish Hanson, Sandra Wilmot, Joshua Halman, Kathy Decker, Tess Greaves AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION STATE OF VERMONT – DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION FOREST RESOURCE PROTECTION PERSONNEL Barbara Schultz Kathy Decker Elizabeth Spinney Forest Health Program Manager Plant Pathologist/Invasive Plant Program Invasive Plant Coordinator Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation Manager/District Manager 111 West Street 100 Mineral Street, Suite 304 Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation Essex Junction, VT 05452-4695 Springfield, VT 05156-3168 1229 Portland St., Suite 201 Work Phone: 802-477-2134 Cell Phone: 802-777-2082 St. -

Vermont Division for Historic Preservation

Vermont Division for Historic Preservation Memo To: Vermont Advisory Council on Historic Preservation From: Jamie Duggan, Senior Historic Preservation Review Coordinator CC: Frank Spaulding, FPR, Laura Trieschmann, SHPO Date: February 16, 2018 Re: Dutton Pines State Park, Dummerston, Vermont In consultation with the Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation, we have identified a project review subject to 22 VSA Chapter 14 that will result in Adverse Effects to Historic Resources at the Dutton Pines State Park in Dummerston, Vermont. Please review the supporting materials provided for a full explanation of existing conditions, identification of historic resources and assessment of adverse effects. Working together in consultation, FPR and DHP have come to agreement on a list of proposed and recommended stipulations that we believe will serve as reasonable and appropriate mitigation, suitable to resolve the adverse effects identified. We are currently working on a rough draft of a Memorandum of Agreement that will reflect the final agreed-upon measures, once we have received your direction and approval. The following are the stipulations we jointly offer for your consideration and discussion at the upcoming ACHP meeting on February 23, 2018. VDHP and Applicant agree as follows: 1. FPR will continue the discussion about the park’s future with local organizations, the community and other interested parties. 2. FPR shall complete A Maintenance Plan for Preservation for the complex within one (1) year from the date of this MOA. a. FPR will utilize the expertise of appropriate subject craftspeople and technicians for the various material concerns (e.g. preservation mason for stone fireplaces and water fountains; log- building expert for Pavilion, roofer, etc.) b. -

2005 Yearbook

VERMONT YOUTH CONSERVATION CORPS 2005 Yearbook Teaching individuals to take personal responsibility for all of their actions. -The VYCC Mission Board of Directors Ron Redmond, Chair Matthew Fargo, Vice Chair Rain Banbury, Secretary Contents Richard McGarry, Treasurer Eric Hanson, Past Chair Judi Manchester, Past Chair Program Overview 4 Caroline Wadhams-Bennett, Past Chair Richard Darby Project Profiles 6 David Goudy Jeffrey Hallo Season Highlights 8 Martha D. McDaniel, M.D. Franklin Motch Field Staff in Focus 10 Lee Powlus Doris Evans, Founder and Board Member Emeritus Alumni Rendezvous 12 Park Crews 15 - 19 Headquarters Staff Wilderness Crews 20 - 22 Thomas Hark, President Jocelyn Haley, Director of Administration and Finance Roving Crews 23 - 31 Polly Tobin, Director of Field Programs Kate Villa, Director of Development Community Crews 32 – 35 Bridgette Remington, Director of Communications and IT Brian Cotterill, Operations Manager Fall Leadership Crews 36 – 37 Lisa Scott, Parks - Americorps Manager Patrick Kell, Program Manager News from HQ 38 Christa Finnern, Program Coordinator John Leddy, Program Coordinator With Special Thanks 42 Heather Nielsen, Program Coordinator Jason Buss, Program Coordinator Alumni Updates 44 Jennifer Hezel, Administrative Coordinator Don Bicknell, Volunteer Extraordinaire Home of the VYCC 46 Yearbook Editor: JP Grogan Copy Editors: Kate Villa, Polly Tobin A Message from the Founding President Dear Alumni and Friends, 2005 marked the 20th anniversary celebration of the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps! We started in 1985 with nothing but passion, a dream of what might be, and a $1 appropriation from the Vermont legislature. Twenty years later, the VYCC has grown into a mature, statewide non-profit organization with a $1.8 million annual budget, 13 year-round staff, three full-time VISTA Volunteers, 22 year-round AmeriCorps Members, and an annual enrollment of over 250 people. -

Campings Vermont

Campings Vermont Alburg Colchester - Alburgh RV Resort and Trailor Sales - Lone Pine Campsite - Goose Point Campground - Malletts Bay Campground Andover, Green Mountains Danville - Horseshoe Acres Campground - Sugar Ridge RV Village-Campground Arlington, Green Mountains Dorset, Green Mountains - Camping on the Battenkill - Dorset RV Park - Howell's Camping Area - Emerald Lake State Park campground Barnard Fairfax - Silver Lake State Park campground - Maple grove campground Barton Fairhaven - Belview Campground - Lake Bomoseen KOA - Half Moon Pond State Park campground Brattleboro, Green Mountains - Bomoseen State Park campground - Brattleboro North KOA - Kampfires Campground in Dummerston Franklin - Lake Carmi State Park campground - Fort Dummer State Park campground - Mill Pond campground Bristol, Green Mountains Groton - Green Mountain Family Campground - Stillwater State Park campground - Ricker Pond State Park campground Burlington - Big Deer State Park campground - North Beach Campground Guildhall Chittenden - Maidstone State Park campground - Chittenden Brook Campground Island Pond Claremont - Brighton State Park campground - Wilgus State Park campground Isle la Motte - Sunset Rock RV Park Jamaica en omgeving - Jamaica State Park campground - West River Camperama in Townshend - Bald Mountain Campground in Townshend - Townshend State Park campground - Winhall Brook Campground in Londenderry Jeffersonville South Hero - Brewster River Campground - Apple Island Resort - Camp Skyland Killington - Gifford Woods State Park campground Stowe, -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in Vermont 2010

FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT 2010 AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION WATERBURY - VERMONT 05671-0601 STATE OF VERMONT PETER SHUMLIN, GOVERNOR AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEBORAH L. MARKOWITZ, SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION Michael C. Snyder, Commissioner Steven Sinclair, Director of Forests http://www.vtfpr.org/ We gratefully acknowledge the financial and technical support provided by the USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry that enables us to conduct the surveys and publish the results in this report. This report serves as the final report for fulfillment of the Cooperative Lands – Survey and Technical Assistance and Forest Health Monitoring programs. FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT CALENDAR YEAR 2010 Frost Damage PREPARED BY: Barbara Burns, Kathy Decker, Tess Greaves, Trish Hanson, Tom Simmons, Sandra Wilmot AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION (Intentionally Blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS Vermont 2010 Forest Health Highlights ....................................................................... 1 Forest Resource Protection Personnel ......................................................................... 12 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 13 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ 13 2010 Publications ....................................................................................................... -

2017 Vermont Moose Hunter's Guide

2017 Vermont Moose Hunter’s Guide Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department HUNTING ON TIMBER COMPANY LANDS The Nature Conservancy The Trust for Public Land Timber companies own thousands of acres of land 27 State Street 33 Court Street across Vermont, especially within the Northeast Montpelier, VT 05602 Montpelier, VT 05602 Kingdom. As a hunter, you will be a guest on their (802) 229-442 (802) 223-1373, ext. 20 land. To ensure that you can continue to enjoy that privilege, please follow these general guidelines: HELPFUL CONTACT INFORMATION 1. No fires 2. Camping not allowed on US Fish & Wildlife VT Fish & Wildlife Department lands or on private lands w/o permission Permit Applications/Processing 3. ATVs are NOT allowed on State or Federal land or lands under conservation easements. Cheri Waters, Administrative Assistant Written permission required on private Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department lands 1 National Life Drive, Dewey Bldg. 4. Don’t hunt near active logging operations Montpelier, VT 05620 - 3208 5. Respect gates and closed roads Phone: 802-828-1190 6. Be careful not to rut roads 7. Do not block roads and trails; park well off Hunter Surveys/Diary Cards the traveled portion of logging roads 8. Give logging trucks the right-of-way Michele Eynon, District Office Chief Clerk 9. Do not litter Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department 374 Emerson Falls Road, Suite 4 Addresses & phone numbers of some major large St Johnsbury VT 05819 landowners are as follows: Phone: 802-751-0100 Heartwood Forestland Fund IV & V, Black Hills, Peter Piper Timber, LLC, LIADSA, & Noble Enterprises State Police Dispatchers c/o LandVest, 5086 US Route 5 Ste 2 (to contact District Game Wardens) Newport, VT 05855 (802) 334-8402 St. -

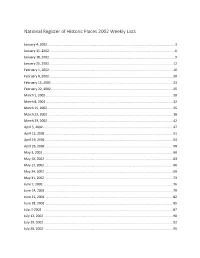

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2002

National Register of Historic Places 2002 Weekly Lists January 4, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 11, 2002 ........................................................................................................................................... 6 January 18, 2002 ........................................................................................................................................... 9 January 25, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 12 February 1, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 16 February 8, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 20 February 15, 2002 ....................................................................................................................................... 23 February 22, 2002 ....................................................................................................................................... 25 March 1, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................. 28 March 8, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................ -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A)

NPS Form 10-900 ft* I\lCSVB) -2280 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) *1 United States Department of the Interior iV"? 1 \ j National Park Service V • "" —-••• — ! '. National Register of Historic Places SAfRf-GISTER OF HISTORIC FLA C?^ Registration Form ^ NATlOrkPARSSERVi CE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1 . Name of Property historic name State Park other names/site number 2. Location street & number 2755 State Forest Road (VT Route 232) for publication city or town ____Townshend______________________ vicinity state Vermont code VT county Windham code 025 zjp C0rje 0^353 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this E nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property 0 meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Brochure Cover

19 Meetinghouse Road, Athens, VT Curtis Trousdale, Owner, Broker, Realtor Cell: 802-233-5589 [email protected] 2004 Williston Road, South Burlington VT 05403 | www.preferredpropertiesvt.com | Phone: (802) 862-9106 | Fax: (802) 862-6266 Aerial map does not reflect recent logging preformed. Stonewall Border Blazes & Flagging Stonewall Border 54+/- Acres Stonewall Border Landing Meetinghouse Rd PROVIDED FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY, NOT INTENDED AS AN ACCURATE REPRESENTATION Additional Property Information 19 Meetinghouse Rd, Athens, VT 05734 Utility & Property Info: Taxes: Town of Athens— 1942.66 (2015 Non-homestead rate). The property has been put into Vermont Current Use for the 2016 tax year. 2 acres were withheld from the program to allow for the construction of a home without withdrawing acreage. Taxes should be greatly reduced for the coming tax year but the town has not yet calculated them. A very rough estimate would be taxes of $270 p/y for 2016. Power: Power poles stop at the last full time residence—16 Meetinghouse Rd, which is the beginning of the class 4/trail section of Meetinghouse Rd. Distance to properties southwestern corner is approximately 1,200 feet. The service provider is Green Mountain Power. Septic: No Soil tests have been completed at this time. Water: There is no formal drinking water at this time. A drilled well is common for this area. Zoning: There is no zoning regulations in Athens. Boundaries: Property is well marked and bounded by a combination of road frontage, corner pins, stone walls, blue blazes and some neon flagging. Services: There is currently no phone, TV, or internet available at this property. -

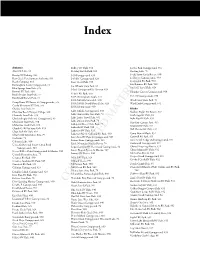

Index.Qxd 2/20/07 2:51 PM Page 1056

17_069295 bindex.qxd 2/20/07 2:51 PM Page 1056 Index Alabama Hilltop RV Park, 931 Service Park Campground, 931 Aliceville Lake, 81 Holiday Trav-L-Park, 930 Sherling Lake, 76 Barclay RV Parking, 929 I-10 Kampground, 931 South Sauty Creek Resort, 930 Bear Creek Development Authority, 931 I-65 RV Campground, 929 Southport Campgrounds, 930 Beech Camping, 931 Isaac Creek Park, 930 Southwind RV Park, 930 Birmingham South Campground, 73 Sun Runners RV Park, 930 Joe Wheeler State Park, 81 Sunset II Travel Park, 929 Blue Springs State Park, 929 John’s Campground & Grocery, 929 Brown’s RV Park, 930 Thunder Canyon Campground, 930 K & K RV Park, 930 Buck’s Pocket State Park, 77 U.S. 78 Campgrounds, 930 Burchfield Branch Park, 72 KOA Birmingham South, 931 KOA McCalla/Tannehill, 930 Wind Creek State Park, 72 Camp Bama RV Resort & Campgrounds, 929 KOA Mobile North/River Delta, 929 Wind Drift Campground, 931 Candy Mountain RV Park, 929 KOA Montgomery, 930 Cheaha State Park, 75 Alaska Cherokee Beach Kamper Village, 930 Lake Eufaula Campground, 930 Alaskan Angler RV Resort, 932 Chewacla State Park, 929 Lake Guntersville State Park, 78 Anchorage RV Park, 84 Chickasabogue Park and Campground, 80 Lake Lanier Travel Park, 931 Auke Bay RV Park, 931 Lake Lurleen State Park, 74 Chickasaw State Park, 930 Bear Paw Camper Park, 932 Chilatchee Creek Park, 929 Lakepoint Resort State Park, 75 Lakeside RV Park, 930 Bestview RV Park, 932 Claude D. Kelley State Park, 929 Bull Shooter RV Park, 932 Clean Park RV Park, 929 Lakeview RV Park, 929 Camp Run-A-Muck, 932 Clear