VU Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thank You Modern Day Superheroes

THANK Y U modern-day superheroes Healthcare workers Essential workers Teachers PMHS 2020 In a digital world dominated by superhero movies, most people tend Superheroes to think of a cape-bearing, Hollywood star when they hear the word "hero." aren't just While science has not yet created the for world's rst bionic being, there are still modern-day heroes who walk among us. comic Instead of comic book protagonists battling grotesque monsters, our modern-day heroes books. are the soldiers who defend our rights, the essential workers who keep society nourished during such unprecedented times, the teachers who provide support through online learning, and the healthcare workers who keep society healthy. For these groups, sacrice is not something that can be digitally created through a green screen. Instead, these unsung heroes of our modern times often face much more tangible risks, especially in regard to their own safety and that of their families. Pandemic or not, the recognition that these workers deserve is nothing short of a hero's welcome. Letters to 1. Healthcare Workers Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, assistants, therapists, etc. Cassidy Chansirik Dear healthcare workers, On behalf of the Pre-Medical Honor Society at UC Berkeley, thank you so much for your continued dedication during these uncertain times. As a community of aspiring healthcare professionals, we are constantly in awe of your passion in a field that is often mentally and emotionally challenging. Thank you for being our role models, and for showing us that empathy and human kindness can still be found even amidst a global pandemic. -

Unit – I Technical English – Shsa1101

SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIT – I TECHNICAL ENGLISH – SHSA1101 1 I. Present Tense Simple present tense is used- For actions in the present which happen usually, habitually or generally, For example: He walks to college every day. For stating general truths. For example: Water boils at 100°C. For describing processes in a general way. For example, A scientist observes phenomena carefully. Some adverbs of frequency with the simple present tense to state how often somebody does something are: always, usually, often, sometimes, occasionally, rarely and never. Note that the adverbs of frequency usually go before the verb. II. Present continuous Censeis used - to express an action going on at the time of speaking. For example: I am lighting the Bunsen burner. The following verbs are not normally used in present continuous tense: Love, like, hate, want, need, prefer, know, realize, suppose, mean, understand, believe, remember, belong, fit, contain, consist, seem I am hungry. I want something to eat. Do you understand what I mean? When ‘think’ means ‘believe’ or ‘have an opinion’ we do not use continuous. I think she is from North India, but I am not sure. What do you think about my future plans? When we mean ‘consider’ the continuous is possible: I am thinking about what happened.I often think about it. She is thinking of giving up her job. We normally use ‘see’, ‘hear’, ‘smell’, ‘taste’ in present simple not continuous with the following verbs: Do you see the man there?The room smells. Let’s 2 open the doors. -

New APWA President Takes Office… See Page 2 Organization Greener Make Your Cut Fleet Costs 15–30% and Improve Service with GIS

New APWA President takes office… See page 2 Organization Greener Make Your Cut Fleet Costs 15–30% and Improve Service with GIS GIS Improves the Productivity and Efficiency of Your Government Fleet Operations Use ESRI ArcLogistics™ to create vehicle routes and mobile workforce schedules that consider time, cost, worker/vehicle specialty, and actual street network drive-times. ArcLogistics combines proven geographic information system (GIS) technology with high-quality street data to create a routing and scheduling solution that builds optimized vehicle routes and provides turn-by-turn directions. ArcLogistics is affordable, easy to implement, and requires minimal training. Create more efficient inspector territories with balanced workloads. Increase daily productivity while using fewer vehicles. Use less fuel and reduce carbon emissions. Quickly audit mileage and accurately monitor work activity. Create dispatcher summary reports, route overview maps, street-level ESRI is the market leader in providing geographic information directions, route manifests, and more. system solutions to organizations around the world. Call 1-888-288-1386 today to find out how you ESRI— e GIS Com pa ny™ can improve your fleet efficiency. 1-888-288-1386 Visit www.esri.com/fleet. [email protected] www.esri.com/fleet Copyright © 2009 ESRI. All rights reserved. The ESRI globe logo, ESRI, ArcLogistics, ESRI—The GIS Company, @esri.com, and www.esri.com are trademarks, or registered trademarks, or service marks of ESRI in the United States, the European Community, or certain other jurisdictions. Other companies and products mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective trademark owners. G34673_APWA-Reporter_Mar09.indd 1 2/4/09 10:43:15 AM October 2009 Vol. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Download the Transcript (PDF)

Residents In a Room Episode Number 14 Episode Title – After Chief Residency Recorded February 2020 (SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC) VOICE OVER: This is Residents in a Room, an official podcast of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, where we go behind the scenes to explore the world from the point of view of anesthesiology Residents. Overall, just a positive effect on this program. Introduce yourself as Dr. Neumann and own it. We’re all just really good team players, I think. BRYCE, HOST: Hello. I’m Bryce Austell, one of the Chief Residents at the Department of Anesthesiology at Rush University Medical Center. We’re back for our third and final episode for Residents in a Room, the podcast for residents by residents with Chief Residents. For the last time, let's go around the table and just say your name and where you're from. LOUISE: I’m Louise Hillen, I am one of the Chief Residents at Northwestern. KAITLYN: Hi. I'm Kaitlyn Neumann. I’m one of the Chief Residents at Northwestern as well. CHRIS: I’m Chris Hull and I’m also from Northwestern. DARRYL: Hi, I’m Darryl Kerr. I am one of the Chief Residents at Rush. JOHN: John Boguski, Chief at Rush. MITCH: And Mitch Bosman, one of the Chiefs at Rush. BRYCE: All right, so now that we are all just a couple months away from graduation and finishing our Chief Residency year, tell us a little bit about what you'll take away from your experience being a Chief Resident. And where do you go from here? MITCH: I don't go very far. -

Saving Lives: Why the Media's Portrayal of Nursing Puts Us All At

SAVING LIVES SAVING LIVES Why the Media’s Portrayal of Nursing Puts Us All at Risk Sandy Summers, RN, MSN, MPH Harry Jacobs Summers UPDATED SECOND EDITION 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Sandy Summers and Harry Jacobs Summers, 2015 Lyrics from Aimee Mann’s “Invisible Ink” used by permission of Aimee Mann/SuperEgo Records All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Summers, Sandy, author. -

Notes Endnotes for Chapter 1

1 Who Are Nurses and Where Have They Gone? • 21 Notes In these endnotes, The Truth About Nursing is abbreviated “TAN” and the Center for Nursing Advocacy as “CFNA.” Please see www.truthaboutnurs ing.org/references/ for live hyperlinks providing easy online access to virtually all of the references cited below. 1. TAN, “Q: Are You Sure Nurses Are Autonomous? Based on What I’ve Seen, It Sure Looks Like Physicians Are Calling the Shots,” accessed January 28, 2014, http:// tinyurl.com/7qfa8zu. 2. Hanne Dina Bernstein, “Reflections: Two Cups: The Healing Power of Tea,” American Journal of Nursing 104, no. 4 (April 2004): 39, http://tinyurl.com/ nqjbyez. 3. Cnet.com, “Biden: ‘Doctors Allow You to Live; Nurses Make You Want to Live’ ” (June 3, 2013), http://tinyurl.com/ks6jlgm. 4. Julie Thao, “Julie Thao’s Speech in Pasadena,” California, January 28, 2010, YouTube video, http://tinyurl.com/obtuutb. 5. International Council of Nurses, “About ICN” (June 14, 2013), http://tinyurl. com/ nxubwo4. 6. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment Statistics: May 2012 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” http://tinyurl.com/q2ywzuv. 7. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), “The Registered Nurse Population: Findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses” (2010), http://tinyurl. com/7zgyet7. 8. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Physicians and Surgeons,” accessed January 8, 2014, http://tinyurl.com/77ghlzk. 9. David I. Auerbach, Douglas O. Staiger, Ulrike Muench, and Peter I. Buerhaus, “The Nursing Workforce: A Comparison of Three National Surveys,” Nursing Economic$ 30, no. -

P'an Ku Magazine, We Have Incorporated Mayan Symbols to to Indicate the Page Numbers

k: BROWARDLITERARY & ARTSCOLLEGEMAGAZINE Spring 2012 / The Mayan Prophecies Though most people think that the Mayans have predicted the end of the world, the truth is that Mayan writing says very little about what will happen during the time leading up to December 21st, 2012. Mayan Prophecies essentially consist of 13 katuns (eachkatun equals 19.7 years) for a total of 256 years, also known as a "short count." Based on ancient Mayan text, we are currently living in the katun 4 Ahau, which began in 1993. The current Mayan Calendar begin date was August 11th, 3114 BC and isbased on what archaeologists, anthropologists, and archaeoastronomers call the "Long Count," which covers a span of 5,125 years. Some researchers believe the Mayan Calander actually began with katun 11 Ahau, which means the Mayan Prophecies will have cycled through the 13 katuns 20 times at the calendar end date of December 21st, 2012, which marks the beginning of katun 2 Ahau. katun 11 Ahau: "Food is scarce during this katun and invading foreigners arrive and disperse the population. There is an end to traditional rule, there are no successors. Since this is thd first katun, it always opens up a new era. It was during the span of this katun, from 1539 1 1559, that the Spanish began their take over of Yucatan and imposed Christianity on the natives..." katun 4|Ahau: "There will be scarcities of corn and squash during this katun and this will lead to great mortality. This was the katun (around 712 - 731 AD) during which the settle- ment of Chichen Itza occurred, when the man-god Kukulcan (Quetzalcoatl) arrived. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Paul Kulikovsky №86 May 2015 Celebrations of the birthday of Emperor Nicholas II Emperor Nicholas II was born 18 May (Old style 6 May) 1868, as the eldest son of the Tsarevich Alexander Alexandrovich, later Emperor Alexander III the Peacemaker, and his wife Maria Feodorovna. He was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Duke of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His official short title was Tsar Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias. In 1981 he was canonized as a martyr by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. This led to the canonization of Nicholas II, his wife Empress Alexandra and their children as passion bearers - a title commemorating believers who face death in a Christ-like manner - on 15 August 2000 by the Russian Orthodox Church. About Emperor Nicholas II.... "In order to understand Emperor Nicholas II, you have to be Orthodox. It is no good being secular or nominally Orthodox, semi-Orthodox, ‘hobby Orthodox’ and retaining your unconverted cultural baggage, whether Soviet or Western – which is essentially the same thing. You have to be consistently Orthodox, consciously Orthodox, Orthodox in your essence, culture and world view. In other words, you have to have spiritual integrity – exactly as the Emperor had, in order to understand him. Emperor Nicholas was profoundly and systematically Orthodox in his spiritual, moral, political, economic and social outlook. His Orthodox soul looked out on the world through Orthodox eyes and acted in an Orthodox way, with Orthodox reflexes. So we too have to be Orthodox in order to understand him. -

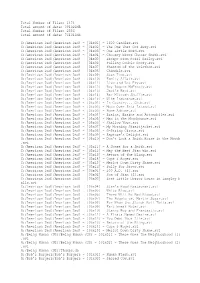

2556 Total Amount of Data: 761041MB G:/America

Total Number of Files: 1474 Total amount of data: 391021MB Total Number of Files: 2556 Total amount of data: 761041MB G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x01] - 1600 Candles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x02] - The One That Got Away.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x03] - One Little Word.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x04] - Choosey Wives Choose Smith.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x05] - Escape From Pearl Bailey.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x06] - Pulling Double Booty.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x07] - Phantom of the Telethon.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x08] - Chimdale.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x09] - Stan Time.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x10] - Family Affair.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x11] - Live and Let Fry.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x12] - Roy Rogers McFreely.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x13] - Jack's Back.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x14] - Bar Mitzvah Shuffle.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x15] - Wife Insurance.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x01] - In Country... Club.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x02] - Moon Over Isla Island.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x03] - Home Adrone.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x04] - Brains, Brains and Automobiles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x05] - Man in the Moonbounce.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x06] - Shallow Vows.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x07] - My Morning Straitjacket.avi G:/American -

Just for Mom

FREE COPY JUST FOR MOM March 2017 MARVELLOUS IDEAS FOR THE SECRET OF CARB CYCLING THE RISE OF SOCIAL ENTERPRISES INCREDIBLE ICELAND1 Signature Society Mag Ads 225x297 FINAL.pdf 1 2/26/17 4:41 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Society 3 MG&D Studs & Drops Society Magazine DPS.ai 1 2/23/17 3:01 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K MG&D Studs & Drops Society Magazine DPS.ai 1 2/23/17 3:01 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K FROM THE MY top 3 EDITOR piCKS othing has the power to change the world like the unconditional love of a mother. Indeed, ‘mother’, or its equivalents, is the most beautiful word in any language. It evokes a spectrum of emotions and ‘I love everything a gamut of feelings in the heart of even the most about water’ Nruthless individual. She is always willing to forgive and accept her Omani sailing star Fahad children with arms wide open, no matter how much they have Al Hasni has always had a gone wrong and hurt her. However, we hardly stop to think of how passion for sailing and the sea. Society caught up with they feel and whether they need help. In a sense, we neglect them Fahad to find out more by not appreciating them enough. about his career and his team’s latest sailing tour P.18 Mother’s Day is just around the corner and it’s that special day that gives you the perfect opportunity to shower your mom with your love and affection. -

Notes Endnotes for Chapter 4 Yes, Doctor!

146 • SAVInG LIVes Notes 1. L. Okey Onyejekwe Jr., “Doctor of Law and Medicine,” California Lawyer (May 2008), http://tinyurl.com/okt3s2z. 2. TNN, “Doctors, Nurses Clash at NRS Hospital,” Times of India (December 10, 2004), http://tinyurl.com/ldtut3v. 3. Joe Kita, “Doctors Confess Their Fatal Mistakes,” and Sunnie Bell, “I Didn’t Question a Doctor I Knew Was Wrong,” Reader’s Digest (October 2010), http:// tinyurl.com/ppjs3z6, http://tinyurl.com/m5hkvgd; TAN, “Death by Disrespect” (October 2010), http://tinyurl.com/qcurmta. 4 Yes, Doctor! No, Doctor! • 147 4. Peter Pronovost, “I Could Have Caused Permanent Brain Damage,” Reader’s Digest (October 2010), http://tinyurl.com/ob6pohh. 5. Kevin Keane, “Nurse Snatched Scalpel Off Doctor about to Cut Vein,”Irish Examiner (December 14, 2013), http://tinyurl.com/p9twqv4; TAN, “Nurse X Confronts a Cutting-Edge Technique” (December 14, 2013), http://tinyurl.com/ n55kq58. 6. Jordan Robertson, “Deputies Tackle Neurosurgeon Outside Oakland Operating Room,” Associated Press (March 2006), http://tinyurl.com/mfr8tta; CFNA, “McDrunky,” TAN (March 9, 2006), http://tinyurl.com/oogtblv. 7. Di Caelers, “Nearly Half of Our Nurses Suffer Abuse” (November 10, 2005), http:// tinyurl.com/oxb4bes; CFNA, “A Short Herstory of Violence,” TAN (November 10, 2005), http://tinyurl.com/oxf3ldg. 8. John Ensslin, “Nurse Sues Memorial, Claims Surgeon Threw Human Tissue at Her,” Colorado Springs Gazette (June 26, 2009), http://tinyurl.com/kh6mdqk; TAN, “Can We Get Cultures on That?” (June 26, 2009), http://tinyurl.com/ odyp44l. 9. Kevin Sack, “Whistle-Blowing Nurse Is Acquitted in Texas,” New York Times (February 11, 2010), http://tinyurl.com/mdvy889; TAN, “Remain in Light” (February 11, 2010), http://tinyurl.com/o9khkr7.