Replacement Or Reduction of Gene-Edited Animals in Biomedical Research: a Comparative Ethics and Policy Analysis Matthias Eggel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

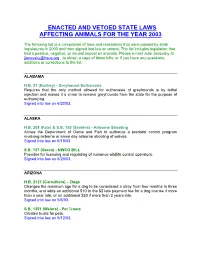

Enacted and Vetoed State Laws Affecting Animals for the Year 2003

ENACTED AND VETOED STATE LAWS AFFECTING ANIMALS FOR THE YEAR 2003 The following list is a compilation of laws and resolutions that were passed by state legislatures in 2003 and then signed into law or vetoed. The list includes legislation that had a positive, negative, or neutral impact on animals. Please e-mail Julie Janovsky at [email protected] , to obtain a copy of these bills, or if you have any questions, additions or corrections to the list. ALABAMA H.B. 37 (Buskey) - Greyhound Euthanasia Requires that the only method allowed for euthanasia of greyhounds is by lethal injection and makes it a crime to remove greyhounds from the state for the purpose of euthanizing. Signed into law on 6/20/03. ALASKA H.B. 208 (Fate) & S.B. 155 (Seekins) - Airborne Shooting Allows the Department of Game and Fish to authorize a predator control program involving airborne or same day airborne shooting of wolves. Signed into law on 6/18/03 S.B. 147 (Green) - NWCO BILL Provides for licensing and regulating of nuisance wildlife control operators. Signed into law on 6/28/03. ARIZONA H.B. 2121 (Carruthers) - Dogs Changes the minimum age for a dog to be considered a stray from four months to three months, and adds an additional $10 to the $2 late payment fee for a dog license if more than a year late, or an additional $20 if more than 2 years late. Signed into law on 5/6/03. S.B. 1351 (Weiers) - Pet Trusts Creates trusts for pets. Signed into law on 5/12/03. -

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition*

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition* Members of the Panel on Euthanasia Steven Leary, DVM, DACLAM (Chair); Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, High Ridge, Missouri Wendy Underwood, DVM (Vice Chair); Indianapolis, Indiana Raymond Anthony, PhD (Ethicist); University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Samuel Cartner, DVM, MPH, PhD, DACLAM (Lead, Laboratory Animals Working Group); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama Temple Grandin, PhD (Lead, Physical Methods Working Group); Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado Cheryl Greenacre, DVM, DABVP (Lead, Avian Working Group); University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee Sharon Gwaltney-Brant, DVM, PhD, DABVT, DABT (Lead, Noninhaled Agents Working Group); Veterinary Information Network, Mahomet, Illinois Mary Ann McCrackin, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACLAM (Lead, Companion Animals Working Group); University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Robert Meyer, DVM, DACVAA (Lead, Inhaled Agents Working Group); Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi David Miller, DVM, PhD, DACZM, DACAW (Lead, Reptiles, Zoo and Wildlife Working Group); Loveland, Colorado Jan Shearer, DVM, MS, DACAW (Lead, Animals Farmed for Food and Fiber Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Tracy Turner, DVM, MS, DACVS, DACVSMR (Lead, Equine Working Group); Turner Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery, Stillwater, Minnesota Roy Yanong, VMD (Lead, Aquatics Working Group); University of Florida, Ruskin, Florida AVMA Staff Consultants Cia L. Johnson, DVM, MS, MSc; Director, -

Advice on Euthanasia Techniques for Small and Large Cetaceans

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2014/111 National Capital Region Advice on Euthanasia Techniques for Small and Large Cetaceans Pierre-Yves Daoust1 and Arthur Ortenburger2 1 Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative Department of Pathology & Microbiology Atlantic Veterinary College University of Prince Edward Island 550 University Avenue Charlottetown, PE C1A 4P3 2 Department of Health Management Atlantic Veterinary College University of Prince Edward Island 550 University Avenue Charlottetown, PE C1A 4P3 January 2015 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2015 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Daoust, P.-Y., Ortenburger, A. 2015. Advice on Euthanasia Techniques for Small and Large Cetaceans. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2014/111. v + 36 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... -

1999 Enacted and Vetoed Animal Legislation

1999 Enacted And Vetoed Animal Legislation The following list is a compilation of laws and resolutions that were passed by state legislatures in 1999 and then signed into law or vetoed. The list includes legislation that had a positive, negative, or neutral impact on animals. For a copy of any of these laws and resolutions, or if you have questions, additions, or corrections, please e-mail Julie Janovsky at [email protected]. ALASKA AK S.B. 74 Game Management Authorizes an employee of the Department of Fish and Game, as part of the game management program, to shoot or assist in shooting wolf, wolverine, fox, or lynx on the same day that the employee is airborne. Vetoed: July 9, 1999 ARIZONA AZ S.B. 1174 Animal Cruelty Penalties Establishes that intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly failing to provide medical attention necessary to prevent protracted suffering to any animal under a person's custody or control is a Class 1 misdemeanor; and establishes that subjecting an animal under a person's custody or control to cruel neglect or abandonment—which results in serious physical injury to the animal—is a Class 6 felony. Signed into law: May 4, 1999 AZ H.B. 2578 Specialty License Plates Allows an organization with less than 200 members to request approval for a special license plate, provided the organization agrees to pay the production and program costs of the special plate. Signed into law: May 4, 1999 ARKANSAS AR H.B. 1442 Animal Shelter Procedures Requires mandatory sterilization of dogs and cats released by pounds, shelters, and humane organizations; and applies to counties with a population of 300,000 or more. -

Full List of Lead Terms and Cross References

BIOETHICS THESAURUS 2011 ABORTED FETUSES ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES ABORTIFACIENTS ALTERNATIVES ABORTION ALTRUISM ABORTION ON DEMAND ALZHEIMER DISEASE Abortion, Induced Use ABORTION AMBULATORY CARE Abortion, Spontaneous Use MISCARRIAGE AMERICAN INDIANS ACADEMIC MEDICAL CENTERS AMNIOCENTESIS Access to Health Care Use HEALTH CARE AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS DELIVERY ANALOGY ACCESS TO INFORMATION ANCIENT HISTORY ACCOUNTABILITY ANENCEPHALY Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Use AIDS ANESTHESIA ACTIVE EUTHANASIA Aneuploidy Use CHROMOSOME ADDICTION ABNORMALITIES ADMINISTRATORS ANIMAL BEHAVIOR ADOLESCENTS ANIMAL CARE COMMITTEES ADOPTION ANIMAL CLONING ADULT CHILDREN ANIMAL EUTHANASIA ADULT STEM CELLS ANIMAL EXPERIMENTATION ADULTERY ANIMAL GROUPS ADULTS ANIMAL ORGANS Adult-Onset Genetic Disorders Use LATE-ONSET ANIMAL PRODUCTION DISORDERS ANIMAL RIGHTS ADVANCE CARE PLANNING ANIMAL TESTING ALTERNATIVES Advance Directive Adherence Use ADVANCE Animal Use Alternatives Use ANIMAL TESTING DIRECTIVES and DIRECTIVE ALTERNATIVES ADHERENCE ANIMAL WELFARE ADVANCE DIRECTIVES Animals, Genetically Modified Use ADVERSE EFFECTS GENETICALLY MODIFIED ANIMALS ADVERTISING Animals, Transgenic Use GENETICALLY ADVISORY COMMITTEES MODIFIED ANIMALS AFRICAN AMERICANS ANONYMOUS TESTING AGE FACTORS Antenatal Diagnosis Use PRENATAL DIAGNOSIS AGED Antenatal Injuries Use PRENATAL INJURIES AGGRESSION ANTHROPOLOGY AGING APO-E GENES AGRICULTURE APTITUDE Ahliyah Use COMPETENCE ARAB WORLD AIDS ARABS AIDS SERODIAGNOSIS ARTIFICIAL FEEDING ALCOHOL ABUSE ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION ALLIED -

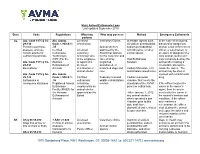

Euthanasia Chart

State Animal Euthanasia Laws Last updated September 2019 State Code Regulations Who may Who may possess Method Emergency Euthanasia perform AL Ala. Code 1975 § 34- Ala. Admin. Licensed Veterinary Clinics Injectable agents such In the case of an injured, 29-130 Code r. 930-X-1- veterinarian as sodium pentobarbital, diseased or dangerous Permit to purchase, .35 Animal shelters sodium pentobarbital animal, a law enforcement possess, and use Certified Licensed approved by the with lidocaine, or other officer, a veterinarian, or certain agents for Euthanasia veterinary Board that operate similar agents an agent or designee of a euthanizing animals Technicians technician who for the collection and local animal control unit (CET) For the is the employee care of stray, Oral Euthanasia may humanely destroy the Ala. Code 1975 § 34- Humane or agent of a neglected, Solution animal after making a 29-131 Euthanasia of licensed abandoned, or reasonable attempt to Exemptions Animals veterinarian or unwanted dogs and Carbon Monoxide, CO, locate the owner. The animal shelter cats and inhalant anesthetics animal may be shot or Ala. Code 1975 § 34- Ala. Admin. injected with a barbiturate 29-132 Code r. 930-X-1- Certified Federally licensed Carbon monoxide drug. Euthanasia in .36 euthanasia wildlife rehabilitation chamber that meets the emergency situations Registered Animal technician centers standards of the AVMA If the officer locates the Euthanasia employed by an panel on euthanasia owner or the owner’s Facility (RAEF) for animal shelter agent, then he or she the Humane approved by the *After January 1, 2012, must notify the owner of Euthanasia of Board any animal shelters the animal’s location and Animals which operated a gas condition. -

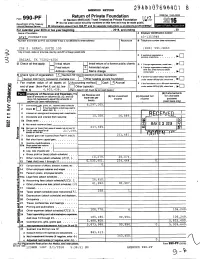

Form 990-PF Or Section 4947 ( A)(1) Trust Treated As Private Foundation \2 ^O^ Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

/ ^V AMENDED RETURN YC7^^V VU 8 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation \2 ^O^ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► and its separate instructions /form990pf. • Internal Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF is at For calendar y ear 2016 or tax y ear beg inning , 2016 , and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number AT&T FOUNDATION 43-1353948 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mall is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 208 S. AKARD, SUITE 100 (800) 591-9663 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here . DALLAS, TX 75202-4206 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organizations , check here. ► El Final return X Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the q 85% test , check here and attach . ► Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization' X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section chantable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation El 4947 ( a )( 1 ) nonexem pt under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method. L_J Cash X Accrual F 11 the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part ll, col. -

AUSVETPLAN Destruction of Animals.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY EMERGENCY PLAN AUSVETPLAN Operational Manual Destruction of animals A manual of techniques of humane destruction Version 3.2, 2015 AUSVETPLAN is a series of technical response plans that describe the proposed Australian approach to an emergency animal disease incident. The documents provide guidance based on sound analysis, linking policy, strategies, implementation, coordination and emergency- management plans. Agriculture Ministers’ Forum This operational manual forms part of: AUSVETPLAN Edition 3 This manual will be reviewed regularly. Suggestions and recommendations for amendments should be forwarded to: AUSVETPLAN — Animal Health Australia Executive Manager, Emergency Preparedness and Response Suite 15, 26–28 Napier Close Deakin ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6232 5522; Fax: 02 6232 5511 email: [email protected] Approved citation: Animal Health Australia (2015). Operational manual: Destruction of animals (Version 3.2). Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN), Edition 3, Agriculture Ministers’ Forum, Canberra, ACT. Publication record: Edition 1: 1991 Edition 2: Version 2.0, 1996 (major update) Edition 3: Version 3.0, 2006 (major update and inclusion of new cost-sharing arrangements) Version 3.1, 2010 (minor update to Sections 3.5 and 4.7; inclusion of foam technology — not currently available in Australia — for depopulation of poultry) Version 3.2, 2015 (minor update to Sections 3.5 and 4.7; inclusion of foam technology — now available in Australia — for destruction of chickens; and incorporation -

Animal Welfare Act. § 19A-20

Article 3. Animal Welfare Act. § 19A-20. Title of Article. This Article may be cited as the Animal Welfare Act. (1977, 2nd Sess., c. 1217, s. 1.) § 19A-21. Purposes. The purposes of this Article are (i) to protect the owners of dogs and cats from the theft of such pets; (ii) to prevent the sale or use of stolen pets; (iii) to insure that animals, as items of commerce, are provided humane care and treatment by regulating the transportation, sale, purchase, housing, care, handling and treatment of such animals by persons or organizations engaged in transporting, buying, or selling them for such use; (iv) to insure that animals confined in pet shops, kennels, animal shelters and auction markets are provided humane care and treatment; (v) to prohibit the sale, trade or adoption of those animals which show physical signs of infection, communicable disease, or congenital abnormalities, unless veterinary care is assured subsequent to sale, trade or adoption. (1977, 2nd Sess., c. 1217, s. 2.) § 19A-22. Animal Welfare Section in Animal Health Division of Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services created; Director. There is hereby created within the Animal Health Division of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, a new section thereof, to be known as the Animal Welfare Section of said division. The Commissioner of Agriculture is hereby authorized to appoint a Director of said section whose duties and authority shall be determined by the Commissioner subject to the approval of the Board of Agriculture and subject to the provisions of this Article. (1977, 2nd Sess., c. -

Austrian Veterinarians' Attitudes to Euthanasia in Equine Practice

animals Article Austrian Veterinarians’ Attitudes to Euthanasia in Equine Practice Svenja Springer 1,* , Florien Jenner 2 , Alexander Tichy 3 and Herwig Grimm 1 1 Unit of Ethics and Human-Animal-Studies, Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Medical University of Vienna, University of Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 2 University Equine Hospital, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-125-077-2687 Received: 3 January 2019; Accepted: 29 January 2019; Published: 30 January 2019 Simple Summary: Euthanasia of companion animals is a challenging responsibility in the veterinary profession. Convenience euthanasia, over-treatment of animals, and financial limitations often present challenging situations in veterinary practice. Only a few empirical investigations have been published which concentrate on the horse owner’s perspective on euthanasia in equine practice. Data findings on veterinarians’ attitudes toward euthanasia in equine medicine are even scarcer. To this end, an anonymous questionnaire-based survey of Austrian equine veterinarians’ examines attitudes to the euthanasia of equine patients in a range of scenarios; to identify factors which may influence decisions on the ending of a horse’s life. The study showed that veterinarians consider contextual and relational factors in their decision-making. They are aware of owners’ emotional bonds with their horses and financial background, however, requests for convenience euthanasia are typically rejected. Although some significant differences between the tested variables, e.g., gender and working experience emerged, the attitudes of the veterinarians were shown to be largely shared. -

Animal Hospice and Palliative Care Guidelines

Animal Hospice and Palliative Care Guidelines Published by the International Association of Animal Hospice and Palliative Care (IAAHPC), Founded 2009 Authors Amir Shanan, DVM. Task Force Chair. Illinois, USA Kris August, DVM. Iowa, USA Kathy Cooney, DVM, MS. Colorado, USA Lynn Hendrix, DVM. California, USA Bonnie Mader, MS. California, USA Jessica Pierce, PhD, MTS. Colorado, USA Acknowledgements We the authors would like to thank the following individuals for sharing their time and expertise in review of this document: Betty Carmack, RN, EdD, Jennifer Coates, DVM, Radford Davis, DVM, MPH, Diplomate ACVPM, Tina Ellenbogen, DVM, Barbara Fougere, BSc, BVMS (hons), BHSc (Comp Med), MHSc (Herb Med), CVA, Sandra Frellsen, MD, Chris HendrixChupa, and Rebecca Rose, CVT. 1 Animal Hospice and Palliative Care Guidelines Table of Contents: I. Introduction II. Purpose and goals of the Guidelines III. Pain, suffering, wellbeing, and quality of life in the animal hospice and palliative care patient 1. Physical and emotional suffering 2. Animals’ individual preferences 3. Quality of Life assessments 4. Recognition of animal pain and pleasure 5. Collaboration and consensus IV. Ethical and legal aspects of providing hospice and palliative care to animals and their caregivers 1. General considerations 2. Euthanasia 3. Pain and suffering 4. Ethical business practices 5. Legal aspects V. Mental Health Considerations in Caring for Animal Hospice and Palliative Caregivers 1. The mental health aspect of caregiving 2. Caregiving experience 3. Experiencing grief 4. Training in mental health and communication 5. When to contact a mental health professional 6. Grief and Bereavement Support for Caregivers 7. Animal Hospice providers’ needs 8. -

Ethical Concerns of Testing Toxins in Animals

Heaven Le A. Roberts ANS 420, 5 March 2015 Ethical Concerns of Testing Toxins in Animals Should not the shepherds take care of the flock? You eat the curds, clothe yourselves with the wool and slaughter the choice animals, but you did not take care of the flock…. this is what the sovereign Lord says: I am against the shepherds and will hold them accountable for my flock. - Ezekiel 34: 2-10 Along with the advice Ezekiel gave to ancient followers of Judaism, our modern society has a wealth of guidelines and regulations regarding the treatment of animals, both domesticated and wild. In the United States, the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) serves as the primary legislation regarding minimums of animal care, in research and otherwise. This act calls for training research personnel in humane animal maintenance and experimentation, testing methods that minimize or eliminate the use of animals (or limit an animal’s pain or distress), and protocol to report deficiencies in animal care and treatment (Animal Welfare Act, 2013). The AWA also recommends replacing animals in research whenever possible, reducing the number of animals, and implementing policies which reduce or eliminate repeated experimentation (Animal Welfare Act, 2013). These principles are known in research as the “3 Rs” (replace, reduce, refine), methodology first publically proposed to the scientific community by Russell and Birch (1959), and one that has been used to modify our methods of animal testing since that time (Usunoff, 2006; The National Academies, 2007; Hoberman, 2012;). These same practices, however, oversee the administration of large doses of known or suspected toxins to animals in order to observe obvious symptoms of disease (The National Academies, 2007; Animal Welfare Act, 2013).