Peacocks and Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

ARIA TOP 20 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2005 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 20 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2005 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 THE SOUND OF WHITE Missy Higgins <P>8 ELEV/EMI ELEVENCD27 2 ANTHONY CALLEA Anthony Callea <P>2 SBME 82876685972 3 SEE THE SUN Pete Murray <P>2 COL/SBME 82876724782 4 AWAKE IS THE NEW SLEEP Ben Lee <P>2 INERTIA IR5210CD 5 TEA AND SYMPATHY Bernard Fanning <P>2 DEW/UMA DEW90172 6 MISTAKEN IDENTITY Delta Goodrem <P>5 EPI/SBME 5189152000 7 REACH OUT: THE MOTOWN RECORD Human Nature <P>3 COL/SBME 82876736392 8 TWO SHOES The Cat Empire <P> EMI 3112212 9 GET BORN Jet <P>8 CAP/EMI 5942002 10 ULTIMATE KYLIE Kylie Minogue <P>2 FMR/WAR 338372 11 LIFT Shannon Noll <P>2 SBME 82876740522 12 THIRSTY MERC Thirsty Merc <P> WEA/WAR 5046788632 13 SHE WILL HAVE HER WAY - THE SONGS OF TIM & NEIL FINN Various CAP/EMI 3404952 14 DOUBLE HAPPINESS Jimmy Barnes <P> LIB/WAR LIBCD71523 15 FINGERPRINTS: THE BEST OF Powderfinger <P>2 UMA 9823521 16 TOGETHER IN CONCERT - JOHN FARNHAM & TOM JONES John Farnham & Tom Jones <P> SBME 82876682212 17 I REMEMBER WHEN I WAS YOUNG - SONGS FROM THE GR… John Farnham <P>2 SBME 82876747652 18 THE SECRET LIFE OF... The Veronicas <P> WARNER 9362493712 19 THE CRUSADER Scribe <P> FMR/WAR 338745 20 SUNRISE OVER SEA The John Butler Trio <P>4 JAR/MGM JBT006 © 1988-2006 Australian Recording Industry Association Ltd. -

Robbie Williams Another Saturday Night

Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Angels - Robbie Williams Let's dance - Chris Rea Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Better be home soon - Crowded House Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Big Yellow Taxi - Counting Crows Lips of an Angel - Hinder Billy Jean - Michael Jackson Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Black fingernails - Eskimo Joe love is in the air - John Paul Young Blame it the Boogie - Jacksons Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Born to be Alive - Patrick Hernandez Love shack - B52's Boys of Summer - The Ataris Love the one you're with - Luther Vandross Brandy - Looking Glass Make Luv - Room 5 Bright side of the road - Van Morrison Makes me wonder - Maroon 5 Breakfast at Tiffanys - Deep blue something Man I feel like a woman - Shania Twain Cable Car - The Fray New York - Eskimo Joe Can't get enough of you baby - smashmouth No such thing - John Mayer Catch my disease - Ben Lee Not in Love - Enrique Iglesius Celebration - Kool and the Gang On the Beach - Chris rea Chain Reaction - John Farnham One more time - Britney Spears Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Play that funky music - Average white band Cheap Wine - Cold Chisel Pretty Vegas - INXS Cherry cherry - Neil Diamond Rehab - Amy Winehouse Choir Girl - Cold Chisel Save the last dance for me - Michael Buble Clocks - Coldplay Second Chance - Shinedown NEW Closing time - Semisonic September - Earth wind and fire Come undone - Robbie Williams -

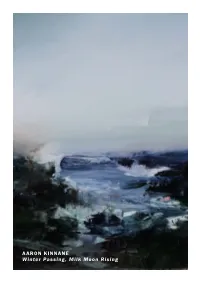

Aaron Kinnane Winter Passing, Milk Moon Rising Aaron Kinnane Winter Passing, Milk Moon Rising

AARON KINNANE Winter Passing, Milk Moon Rising AARON KINNANE Winter Passing, Milk Moon Rising 12 - 28 November 2015 Aaron Kinnane engages with painting in its purest form to perpetuate his effervescent vision of the natural world. Visceral layers of paint form sublime and atmospheric landscapes that are at once sullen and savage, bleak and beautiful, heavy and , desolate and wildly alive. The resulting aesthetic equilibrium spawns a purification that pushes the viewer beyond a physical and visual appreciation of the works into a metaphysical meditation. Kinnane’s new series of work continues the artist’s exploration of the suggested landscape. Lavish layers of midnight navies, hand-mixed mauves, icy blues, arctic greys and army greens reconstruct impressions from the artist’s subconscious. The images appear as hazy recollections, revenant visions lingering in the liminal space between form and formlessness. Moving away from the singular viewpoints of his last series, Kinnane’s new paintings vary in perspective from the sublimity of soaring heights to the intimacy of ground level. Tempestuous, wintry folds of oil conjure stormy seas, snowy fields, rugged cliffs and grassy wilderness – atmospheric landscapes that oscillate between abstraction and representation. Bruised and scarred topographies exude feelings of isolation, yet it is a contented solitude that speaks not of despair but of hope. Using his palette knife as a material extension of his psyche, Kinnane effaces and rebuilds his forms – breaking down planes, pushing horizons and morphing shapes. These paradoxical moments of raw intuition and analytical precision conjure an energy that is at once wildly emotional and quietly cathartic. Kinnane’s long-time love of music is embedded in his work, the artist having grown up in Newcastle with the guys from Silverchair and travelled through India with Ben Lee and Missy Higgins. -

Ben Lee Deeper Into Dream Lojinx/Sonic

Ben Lee Deeper Into Dream Lojinx/Sonic There's a quote out there that says, "Dreams are only thoughts you didn't have time to think about during the day." Aussie-born singer/songwriter Ben Lee reaches beyond such a notion and turns it upside down in order to grab hold of the unconscious. On Deeper Into Dream he examines the intricate layers of dreams, looking to make sense out of life's most complex questions and ideals. "I find dreams to be incredibly honest despite the kind of world we live in," Lee says. "[Dreams are] proof that every single person on the planet is an artist and is completely creative. I really don't like that elitist attitude to art – I like the idea that we are all creative and dreams prove it because people create entire worlds every night." The ARIA award-winning musician's fascination with dreams and the mysteries behind them has long been a part of 20-plus years in the music business. But only now does the former Noise Addict singer, whose early years saw releases on the Beastie Boys' Grand Royal label and Thurston Moore’s Ecstatic Peace! imprint, feel it's the right time to explore that. In the last several, three of which were spent working with the late therapist Jan Lloyd, Lee fell in love with the mysteries that dreaming presents. After he and his wife, actress Ione Skye, welcomed their daughter, Goldie Priya, in 2009, Lee thought it was time to re-examine things, especially the hidden messages inside his own dreams. -

Hayley Solo Acoustic Songlist 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 3Am

1300 738 735 phone [email protected] email www.blueplanetentertainment.com.au web www.facebook.com/BluePlanetEntertainment Hayley Solo Acoustic Songlist 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Closing Time Semisonic 3am Matchbox 20 Crazy Gnarles Barkley A Team Ed Sheeran Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Across The Universe The Beatles Cryin Aerosmith Addicted to You David Guetta Dakota Stereophonics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow Daughters John Mayer All I Want Is You U2 Daydream Believer The Monkees All The Small Things Blink 182 Do Wah Diddy Diddy Manfred Mann Amazing Alex Lloyd Dolphins Cry Live Angels Robbie Williams Don’t Dream Its Over Crowded House Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Don’t Look Back In Anger Oasis Back to Black Amy Winehouse Don’t Say You Love Me M2M Bad Romance Lady Gaga Don't Panic Coldplay Barenaked Jennifer Love Hewitt Downtown Petula Clark Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Drive Incubus Better Man Pearl Jam Drops of Jupiter Train Better Man Robbie Williams Dynamite Taio Cruz Big Yellow Taxi Joni Mitchell Eight Days A Week The Beatles Blackbird The Beatles Eleanor Rigby The Beatles Blank Space Taylor Swift Even When I’m Sleeping Leonardo’s Bride Blister In The Sun Violent Femmes Everlong Foo Fighters Brand New Key Melanie Every Breath You Take The Police Breakeven The Script Everything I Do, I Do It For You Bryan Breakfast At Tiffany's Deep Blue Something Adams Breathe Taylor Swift Everywhere Michelle Branch Brick Ben Folds Five Faith George Michael Bridal Train The Waifs Fall At Your Feet Crowded House Brown -

Acoustic Avenue Duo/Trio Song List

ACOUSTIC AVENUE DUO/TRIO SONG LIST This list does not include all songs performed Aint Seen Nothin Yet Bachman Turner Leaving On a Jet Plane Bob Dylan Across The Universe The Beatles Mr Jones Counting Crows Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers My Happiness Powderfinger All I Have To Do The Everly Brothers Mrs. Robinson Simon and Garfunkle Amazing Alex Lloyd Open Your Eyes Snow Patrol Another Lonely Day Ben Harper Only Wanna be with you Hootie and The Blowfish April Sun Dragon Peaches and Cream John Butler Trio Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Purple Sneakers You Am I Better Man Pearl Jam Put Your Records On Corinne Bailey Rae Breakfast at Tiffanys Deep Blue Something Passenger Powderfinger Boys Light Up Australian Crawl Pictures Sneaky Sound System Baby I Love Your Way Pater Frampton Run To Paradise The Choirboys Bad Moon Rising CCR Steal My Kisses Ben Harper Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Summer Of 69 Bryan Adams Black Finger Nails Eskimo Joe Save Tonight Eagle Eye Cherry Clocks Coldplay Somebody Told Me The Killers Cherry Bomb John Mellencamp Stuck In The Middle Steelers Wheel Dumb Things Paul Kelly Strong Enough Sheryl Crow Drugs Don’t Work The Verve Sitting On The Dock Otis Redding Down Hearted Australian Crawl Suddenly I see KT Tunstall Don’t Dream Its Over Crowded House Something So Strong Crowded House Dreams Fleetwood Mac Shot Through The Heart Bon Jovi Daydream Believer The Monkeys Take It Easy The Eagles Don’t Look Back Oasis 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Don’t Stop Fleetwood Mac Throw Your Arms Hunters and Collectors Down On The Corner -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

The Issues of Gun Violence, Mass Shootings, Racism and Discrimination in the United States

JANUARY 2019 A Gripping New British Drama Broken PAGE 8 At Last! Season 3 premieres Doc Martin Sunday, January 13 Season 8 PAGE 16 THE QUEEN IS BACK CONTENTS 2 3 4 6 21 22 PERKS + EVENTS NEWS + NOTES AUDIO TV LISTINGS TV LISTINGS PASSPORT Magnificent KQED Learn Wins Radio Schedule Cover Story World Highlights The Royal Collection Magnolias New Prize Radio Specials Saturday Movie Kids Highlights Podcasts Coming in February PERKS + EVENTS Member Day: SF Botanical Garden Friday, January 25 PERK San Francisco Join KQED at the San Francisco Botanical Garden (SFBG) for Magnificent Magnolias — one of San Francisco’s annual natural spectacles. Watch as nearly 100 towering magnolias erupt into saucer-sized blossoms, offering up dramatic color and fragrant scents. Admission is free on Friday, January 25, for KQED members (up to two admissions total) who present a current KQED MemberCard and valid ID in person at the ticket booth. The day also includes special discounts on SFBG memberships, in the Garden Bookstore and at the Plant Arbor. sfbg.org Kid Koala at SFJAZZ Friday, February 8 PERK PERK PERK San Francisco Looking for some new music? Check out Montreal-based DJ, composer and producer Kid Koala and the enchanting adaptation of his graphic novel Nufonia Must Fall, coming to SFJAZZ February KID KOALA. KQED; COURTESY COURTESY 7-10. The performance features live puppeteering filmed on a dozen miniature KQED Silicon Valley Conversations sets and projected on video screens, backed by an KQED.ORG Examines Commuting Tuesday, February 5 ensemble of strings, piano San Francisco and electronic instruments. -

Doctor of Philosophy

A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences University of Western Sydney March 2007 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................ VIII LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................... VIII LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS ............................................................................ IX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. X STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP .................................................................. XI PRESENTATION OF RESEARCH............................................................... XII SUMMARY ..................................................................................................XIV CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING MUSIC FESTIVALS AS POSTMODERN SITES OF CONSUMPTION.............................................................................1 1.1 The Aim of the Research ................................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Consumer Society............................................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Consuming ‘Youth’........................................................................................................................ 10 1.4 Defining Youth .............................................................................................................................. -

VICE Studios and Screen Australia Present in Association with Film Victoria and Create NSW a Blue-Tongue Films and Pariah Production

VICE Studios and Screen Australia present In association with Film Victoria and Create NSW A Blue-Tongue Films and Pariah Production Written and Directed by Mirrah Foulkes Starring Mia Wasikowska and Damon Herriman Produced by Michele Bennett, Nash Edgerton and Danny Gabai Run Time: 105 Minutes Press Contact Samuel Goldwyn Films [email protected] SYNOPSES Short Synopsis In the anarchic town of Seaside, nowhere near the sea, puppeteers Judy and Punch are trying to resurrect their marionette show. The show is a hit due to Judy's superior puppeteering, but Punch's driving ambition and penchant for whisky lead to an inevitable tragedy that Judy must avenge. Long Synopsis In the anarchic town of Seaside, nowhere near the sea, puppeteers Judy and Punch are trying to resurrect their marionette show. The show is a hit due to Judy's superior puppeteering, but Punch's driving ambition and penchant for whisky lead to an inevitable tragedy that Judy must avenge. In a visceral and dynamic live-action reinterpretation of the famous 16th century puppet show, writer director MIRRAH FOULKES turns the traditional story of Punch and Judy on its head and brings to life a fierce, darkly comic and epic female-driven revenge story, starring MIA WASIKOWSKA and DAMON HERRIMAN. 2 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT JUDY AND PUNCH is a dark, absurd fable treading a line between fairy-tale, fantasy and gritty realism, all of which work together to establish a unique tone while upsetting viewer expectations. When Vice Studios’ Eddy Moretti and Danny Gabai approached me with the idea of making a live action, feminist revenge film about Punch and Judy, they encouraged me to let my imagination go wild and take the story wherever I felt it needed to go. -

Poco Loco Song List Newly Added Music Classic Pop / Dance

Poco Loco Song List Newly added Music Just the way you are - Bruno Mars Break even - The Script Closer - Chris Brown Love Story - Taylor Swift Forget you - Cee Lo Green Cry for you - September Pack up - Eliza Doolittle The boy does nothing - Alesha Dixon OMG - Usher Mercy - Duffy I've got a feeling - Black eyed Peas Rain - Dragon Bad Romance - Lady Ga Ga Dakota - Stereophonics Poker face - Lady Ga Ga California Gurls - Katy Perry Alejandro - Lady Ga Ga Don't hold Back - Pot Beleez I'm yours - Jason Mraz Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Hey Soul Sister - Train Like it like that - Guy Sebastian Escape(The Pina Colada Song Smile - Uncle Kracker Sweet about me - Gabriella Cilma Save the lies - Gabriella Cilmi Apologize - One Republic Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Let's dance - Chris Rea Addicted to Bass - Amiel Let's get the party started - Pink Ain't nobody - Chaka Khan Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire All I wanna do - Sheryl Crow Lets hear it for the boy - Denise Williams Amazing - George Michael Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Angels - Robbie Williams Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Love at first sight - Kylie Minogue Around the the world - Lisa Stanfield Love fool - Cardigans Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Bad girls - Donna Summer love is in the air - John Paul Young Beautiful - Disco Montego Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Believe - Cher Love shack - B52's Bette Davis eyes - Kim Carnes