Poetics of Dislocation: Comparative Cosmopolitanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reimagining the Brontës: (Post)Feminist Middlebrow Adaptations and Representations of Feminine Creative Genius, 1996- 2011

Reimagining the Brontës: (Post)Feminist Middlebrow Adaptations and Representations of Feminine Creative Genius, 1996- 2011. Catherine Paula Han Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Literature) Cardiff University 2015 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Ann Heilmann for her unflagging enthusiasm, kindness and acuity in matters academic and otherwise for four years. Working with Professor Heilmann has been a pleasure and a privilege. I am grateful, furthermore, to Dr Iris Kleinecke-Bates at the University of Hull for co-supervising the first year of this project and being a constant source of helpfulness since then. I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Judith Buchanan at the University of York, who encouraged me to pursue a PhD and oversaw the conception of this thesis. I have received invaluable support, moreover, from many members of the academic and administrative staff at the School of English, Communication and Philosophy at Cardiff University, particularly Rhian Rattray. I am thankful to the AHRC for providing the financial support for this thesis for one year at the University of Hull and for a further two years at Cardiff University. Additionally, I am fortunate to have been the recipient of several AHRC Research and Training Support Grants so that I could undertake archival research in the UK and attend a conference overseas. This thesis could not have been completed without access to resources held at the British Film Institute, the BBC Written Archives and the Brontë Parsonage Museum. I am also indebted to Tam Fry for giving me permission to quote from correspondence written by his father, Christopher Fry. -

Issue 1 Spring 2017 Left: the Market Cross at Ripley Which Is Probably Medieval with the Stocks in Front

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall IIssssuuee 11 SSpprriinngg 22001177 In this issue: Withernsea Lighthouse Museum Martha Brown a Loyal Servant and Friend of the Brontë family Bridlington Railway Seaside Holiday Posters Medieval Wall Painting in Holy Trinity Church, Wensley Anglo-Saxon Stone Carvings and a Burial at Holy Trinity Church, Wensley To Walk Invisible - A BBC drama production of the Brontë sisters’ Withernsea Lighthouse Museum The lighthouse is 127 feet (38m) high and there are 144 steps to the lamp room. It was built between 1892 and 1894 because of the high number of shipwrecks that were occurring at Withernsea when vessels could not see the lights at either Spurn Head or Flamborough. It was not designed to be lived in, the tower has no dividing floors only the spiral staircase leading to the Service and Lamp Rooms at the top. The Lighthouse was decommissioned at the end of June 1976 and is now a museum of memorabilia about the RNLI Coastguards and local history. The museum also houses an exhibition on the life of actress Kay Kendall (1926-1959) who was a film star in the 1950s. She was born in the town and died of leukaemia. Insert: Inside the lighthouse displaying memorabilia of the RNLI Coastguards. 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 1 Spring 2017 Left: The Market Cross at Ripley which is probably medieval with the stocks in front. The Boar’s Head Hotel partly covered with ivy can be seen in the background. Photograph by Jeremy Clark Cover: The Parish Church of St Oswald, Leathley. Photo by Jeremy Clark Editorial he aim of the Yorkshire Journal is to present an extensive range of articles to satisfy a variety of reading tastes for our readers to enjoy. -

Ii Introduction: Picturing Charlotte Brontë

1 Ii Introduction: picturing Charlotte Brontë Amber K. Regis and Deborah Wynne In response to the centenary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth in 1916, the Brontë Society commissioned a volume of essays entitled Charlotte Brontë, 1816– 1916: A Centenary Memorial (1917), with contributions by some well- known literary fi gures, including G. K. Chesterton and Edmund Gosse. It opened with a foreword by the then president of the Brontë Society, Mrs Humphry Ward, in which she explained that the book set out to off er ‘fresh impressions and the fi rst- hand research of competent writers who have spoken their minds with love and courage’ (Ward, 1917 : 5). One hundred years later, the current volume of essays, Charlotte Brontë: Legacies and Afterlives , also strives to off er ‘fresh impressions’ based on the ‘fi rst- hand research’ of ‘competent writers’; equally, most of the contributors can claim that a love of Brontë’s work motivated this project. However, while the contributors to the 1917 volume considered courage to be required to assert Charlotte Brontë’s importance, the writers in this book show no inclination to defend her reputation or argue for the signifi cance of her work. Her ‘genius’, a term emphasised repeatedly, often anxiously, in the 1917 collection, can now be taken for granted, and for that comfortable assumption we have generations of feminist scholars to thank. Th e current volume instead charts the vast cultural impact of Charlotte Brontë since the appearance of her fi rst published work, Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (1846), highlighting the richness and diversity of the author’s legacy, her afterlife and the continuation of her plots and characters in new forms. -

To Walk Invisible: the Brontë Sisters

Our Brother’s Keepers: On Writing and Caretaking in the Brontë Household: Review of To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters Shannon Scott (University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA) To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters Writer & Director, Sally Wainwright BBC Wales, 2016 (TV film) Universal Pictures 2017 (DVD) ***** In Sally Wainwright’s To Walk Invisible, a two-part series aired on BBC and PBS in 2016, there are no rasping coughs concealed under handkerchiefs, no flashbacks to Cowen Bridge School, no grief over the loss of a sister; instead, there is baking bread, invigorating walks on the moor, and, most importantly, writing. Wainwright dramatises three prolific years in the lives of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë when they composed their first joint volume of poetry and their first sole-authored novels: The Professor, rejected and abandoned for Jane Eyre (1847), Wuthering Heights (1847), and Agnes Grey (1847), respectively. The young women are shown writing in the parlour surrounded by tidy yet threadbare furniture, at the kitchen table covered in turnips and teacups, composing out loud on the way to town for more paper, or while resting in the flowering heather. For Charlotte, played with a combination of reserve and deep emotion by Finn Atkins, to “walk invisible” refers to their choice to publish under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, but in Wainwright’s production, it also refers to invisibility in the home, as the sisters quietly take care of their aging and nearly-blind father, Reverend Patrick Brontë (Jonathan Price), and deal with the alcoholism and deteriorating mental illness of their brother, Branwell (Adam Nogaitis). -

The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë

The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë by Syrie James READING GROUP GUIDE 1. Discuss the Brontë family dynamics. Describe Charlotte’s relationship with her sisters, Emily and Anne. Why was Charlotte so devoted to her father? How did her relationship with her brother Branwell evolve and change over the years, and what influence did he have on her life? 2. What secrets did Charlotte and her siblings each keep, and why? Whose secret had the most devastating impact on the family? How did Charlotte’s secret affect her life and her work? 3. Who are your favorite characters in the novel, and why? Who is your least favorite character? 4. What are your favorite scenes in the novel? What was the saddest scene? The happiest? The most uplifting? Did any scene make you laugh or cry? 5. Discuss Charlotte’s relationship with Mr. Nicholls. When does he begin to care for Charlotte? How does he quietly go about pursuing her? How does the author maintain romantic tension between the two? Do you think Mr. Nicholls changes and grows over the course of the story? 6. In Chapter Five, Charlotte tells Ellen Nussey, “I am convinced I could never be a clergyman’s wife.” She lists the qualities she requires in a husband. How does Mr. Nicholls measure up to these expectations? What are his best and worst qualities? Why is Charlotte reluctant to accept Mr. Nicholls’s proposal? What does Charlotte learn about herself—and her husband—after she marries? Do you think he turns out to be the ideal match for her? 7. -

To Walk Invisible: the Brontë Sisters | All Governments Lie | the Great War | Strike a Pose | Keep Quiet | Rachel Carson Scene & Heard

July-August 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 4 IN THIS ISSUE To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters | All Governments Lie | The Great War | Strike A Pose | Keep Quiet | Rachel Carson scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: Experience Baker & Taylor is the ELITE most experienced in the Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and business; selling A/V customized services to meet continued patron demand products to libraries since 1986. PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review To Walk Invisible: and the delicate reticence of Anne (Charlie Murphy)—while also portraying Branwell The Brontë Sisters (Adam Nagaitis) and their father Patrick HHHH (Jonathan Pryce) with a touching degree of PBS, 120 min., not rated, sympathy, given the obvious flaws of both Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman DVD: $29.99, Blu-ray: $34.99 men. In addition to the drama surrounding Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Branwell’s troubles, the narrative explores The most significant Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman the almost comical difficulties that the period (1845-48) in the sisters confronted in trying to protect their Graphic Designer: Carol Kaufman lives of 19th-century “intellectual property” interests while also British authors Anne, Marketing Director: Anne Williams preserving their anonymity after their nov- Charlotte, and Emily els became wildly popular. -

Women Writers on Film

Women Writers on Film A REPRESENTATION OF THE WORK AND LIVES OF MARY SHELLEY AND THE BRONTË SISTERS THROUGH LITERARY BIOPICS Krista Bombeeck English Language and Culture Semester 2 Bombeeck – S4662687 2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teachers who will receive this document: Chris Louttit and Odin Dekkers Title of document: BA thesis Name of course: BA Thesis Course Date of submission: 15th August 2019 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed: Name of student: Krista Bombeeck Student number: s4662687 Bombeeck – S4662687 3 Table of contents ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 PRIVATE OR PUBLIC: PUBLISHING PROBLEMS ................................................................................................... 13 ANALYSIS .......................................................................................................................................................... 16 CHAPTER 2 ........................................................................................................................................................ -

The Brontë Sisters When to Watch from a to Z Listings for 3-1 Are on Pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – March 2017 P

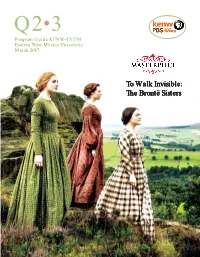

Q2 3 Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University March 2017 To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters When to watch from A to Z listings for 3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – March 2017 P. Allen Smith’s Garden Home – Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. (except 4th) American Woodshop – Saturdays, 6:30 a.m.; Thursdays, 11:00 a.m. Paint This with Jerry Yarnell – Saturdays, 11:00 a.m. America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. (except 11th) PBS NewsHour – Weekdays, 6:00 p.m./12:00 midnight America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 7:30 a.m.; Mondays, 11:30 a.m. PBS NewsHour Weekend – Sundays, 5:00 p.m.(5th, 26th only) Antiques Roadshow – Quilt in a Day – Saturdays, 12:30 p.m. Mondays, 7:00 p.m./8:00 p.m. (20th, 27th only)/11:00 p.m.; Sundays, 7:00 a.m. Quilting Arts – Saturdays, 1:00 p.m. Are You Being Served? Again – Saturdays, 8:00 p.m. (25th only) Red Green Show – Thursdays, 9:30 p.m. (except 9th, 16th); Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. (4th, 25th only) Saturdays, 8:30 p.m. (25th only) Austin City Limits – Saturdays, 9:00 p.m./12:00 midnight Religion and Ethics – Sundays, 3:30 p.m. (except 19th); Wednesdays, 5:00 p.m. Barbecue University – Thursdays, 11:30 a.m Report from Santa Fe – Saturdays, 6:00 p.m. BBC Newsnight – Fridays, 5:00 p.m. Rick Steves’ Europe – Mondays, 10:30 p.m. BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m./4:30 p.m. -

Bronte Syllabus

WOMEN’S LITERATURE: THE BRONTËS ENGL 3924/WMST 3720 · SPRING 2018 · TU/TH 9:30-10:50 AM · LANG 215 DR. NORA GILBERT OFFICE: LANG 408-E EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE HOURS: TU/TH 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM COURSE DESCRIPTION: Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë burst onto the literary scene almost simultaneously in 1847, as their novels Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey were published under the pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Many early critics believed that all “Bell” creations were in fact written by one author, and there continues to be a perception that the Brontës’ writings can be read as one interconnected oeuvre. This class will, to some extent, propagate that perception, focusing as it does on the major works of the three sisters collectively. But it will also highlight the very different ideological standpoints that can be found in each author’s work, and will consider why the field of literary studies is so invested in mythologizing the Brontë sisterhood. A particular focus of this “women’s literature” course will be on the issues of gender and sexuality that play such a pivotal role in all of the Brontës’ novels. To many Victorian readers, these novels seemed quite radical in their representations of women’s rights, sexual desire, and the institution of marriage; to many 21st-century readers, the Brontë sisters have become feminist icons whose works offer inspiring portraits of strong heroines and damning critiques of patriarchal injustices. Yet there are also many ways in which the novels can be seen to work with rather than against the conventions and prejudices of their time, as we will be sure to discuss as well. -

Alice Spawls ꞏ If It Weren’T for Charlotte: the Brontës ꞏ LRB 16 Nov

Alice Spawls ꞏ If It Weren’t for Charlotte: The Brontës ꞏ LRB 16 Nov... https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n22/alice-spawls/if-it-werent-for-charlotte Back to article page Alice Spawls on the Brontës A wood engraving by the illustrator Joan Hassall, who died in 1988, shows Elizabeth Gaskell arriving at the Brontë parsonage. Patrick Brontë is taking Gaskell’s hand; Charlotte stands between them, arms open in a gesture of introduction. We – the spectators, whose gaze Charlotte seems to acknowledge (or is she looking at her father apprehensively?) – stand in the doorway; the participants are framed in the hallway arch, with the curved wooden staircase behind them. On the half-landing is the grandfather clock Patrick used to wind up at 9 o’clock every night on his way to bed (so Charlotte’s friend Ellen Nussey remembered), though the original grandfather clock was sold in 1861 after Patrick’s death, and in any case stood in an alcove, as its replacement does now, and couldn’t be seen from the front door. Gaskell first visited Haworth in September 1853 – she described it in two letters to friends, one of which she reproduced in her Life of Charlotte Brontë, and Charlotte and Gaskell discussed the arrangements in the letters they exchanged. ‘Come to Haworth as soon as you can,’ Charlotte wrote on 31 August, ‘the heath is in bloom now; I have waited and watched for its purple signal as the forerunner of your coming.’ In the event a thunderstorm before Gaskell’s arrival ruined the heather’s glorious colour.[*] 1 di 25 06/10/2018, 16.51 Alice Spawls ꞏ If It Weren’t for Charlotte: The Brontës ꞏ LRB 16 Nov.. -

The Brontë Myth Seminar

LIT3065 The Brontës Module convenor: Dr Amber Regis [email protected] Week 1: The Brontë Myth Seminar: Introductions Workshop: To Walk Invisible (2016) Week 2: Juvenilia and Poetry Seminar: Glass Town, Angria and Gondal Workshop: Poems by Ellis, Acton and Currer Bell (1846) Week 3: Jane Eyre* Seminar: Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) Workshop: Jane Eyre (dir. Robert Stevenson, 1943/1944) Week 4: Wuthering Heights Seminar: Wuthering Heights (1847) Workshop: Wuthering Heights (dir. Anthea Arnold, 2011) Week 5: Agnes Grey Seminar: Agnes Grey (1847) Workshop: Reviewing the Brontës Week 6: Branwell Seminar: Branwell Brontë Workshop: Mrs Gaskell’s Branwell Week 7: The Art of the Brontës Seminar: The Art of the Brontës Workshop: Brontë Portraits EASTER Week 8: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Seminar: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) Workshop: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (BBC Television, dir. Mike Barker, 1996) Week 9: Shirley Seminar: Shirley (1849) Workshop: Shirley (BBC Radio, dir. Tracey Neale, 2014) Week 10: Villette Seminar: Villette (1853) Workshop: Villette (BBC Radio, dir. Tracey Neale, 2009) Week 11: Deaths and Afterlives Seminar: Brontë Deaths Workshop: The Parsonage Museum and Brontë Bicentenaries *NB: Due to Jane Eyre being primary reading on the core module, LIT3101 Romantic and Victorian Prose, we will not be covering the novel directly on LIT3065. We will, instead, consider how the novel has been subject to post-colonial and neo-Victorian re-readings/re-writings, focusing upon Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. Duals students not taking LIT3101 are invited to attend the lectures on Jane Eyre in the Autumn semester. -

Stories of the Past: Viewing History Through Fiction

Stories Of The Past: Viewing History Through Fiction Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Green, Christopher Citation Green, C. (2020). Stories Of The Past: Viewing History Through Fiction (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, UK. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 04/10/2021 08:03:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623069 STORIES OF THE PAST: VIEWING HISTORY THROUGH FICTION Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Christopher William Green January 2020 Frontispiece: Illustration from the initial serialisation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D'Urbervilles.1 1 Thomas Hardy, 'Tess of the D’Urbervilles', The Graphic, August 29th, 1891. ii The material being presented for examination is my own work and has not been submitted for an award of this or another HEI except in minor particulars which are explicitly noted in the body of the thesis. Where research pertaining to the thesis was undertaken collaboratively, the nature and extent of my individual contribution has been made explicit. iii iv Abstract This thesis investigates how effective works of fiction are, through their depictions of past worlds, in providing us with a resource for the study of the history of the period in which that fiction is set. It assesses past academic literature on the role of fiction in historical understanding, and on the processes involved in the writing, reading, adapting, and interpreting of fiction.