Prologue to the Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012

United Nations S/2012/550 Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, and 2, 3, 9 and 11 July 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 9 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-58099 (E) 271112 281112 *1258099* S/2012/550 Annex to the identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Monday, 9 July 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2200 hours on it July 2012, an armed terrorist group abducted Chief Warrant Officer Rajab Ballul in Sahnaya and seized a Government vehicle, licence plate No. 734818. 2. At 0330 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on the law enforcement checkpoint of Shaykh Ali, wounding two officers. 3. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device as a law enforcement overnight bus was passing the Artuz Judaydat al-Fadl turn-off on the Damascus-Qunaytirah road, wounding three officers. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

Salvaging Syria's Economy

Research Paper David Butter Middle East and North Africa Programme | March 2016 Salvaging Syria’s Economy Contents Summary 2 Introduction 3 Institutional Survival 6 Government Reach 11 Resource Depletion 14 Property Rights and Finance 22 Prospects: Dependency and Decentralization 24 About the Author 27 Acknowledgments 27 1 | Chatham House Salvaging Syria’s Economy Summary • Economic activity under the continuing conflict conditions in Syria has been reduced to the imperatives of survival. The central government remains the most important state-like actor, paying salaries and pensions to an estimated 2 million people, but most Syrians depend in some measure on aid and the war economy. • In the continued absence of a political solution to the conflict, ensuring that refugees and people in need within Syria are given adequate humanitarian support, including education, training and possibilities of employment, should be the priority for the international community. • The majority of Syrians still living in the country reside in areas under the control of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, which means that a significant portion of donor assistance goes through Damascus channels. • Similarly, any meaningful post-conflict reconstruction programme will need to involve considerable external financial support to the Syrian government. Some of this could be forthcoming from Iran, Russia, the UN and, perhaps, China; but, for a genuine economic recovery to take hold, Western and Arab aid will be essential. While this provides leverage, the military intervention of Russia and the reluctance of Western powers to challenge Assad mean that his regime remains in a strong position to dictate terms for any reconstruction programme. -

Security Council Distr.: General 16 October 2012

United Nations S/2012/503 Security Council Distr.: General 16 October 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 28 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May and 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25 and 27 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 24 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-55137 (E) 011112 011112 *1255137* S/2012/503 Annex to the identical letters dated 28 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 24 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 23 June 2012 at 2020 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks in Rif Dimashq. 2. On 23 June 2012 at 2100 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement checkpoints in Shaifuniyah, Shumu' and Umara' in Duma, killing Private Muhammad al-Sa‘dah and wounding three soldiers, including a first lieutenant. 3. -

Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1649

6.11.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 370 I/7 COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2020/1649 of 6 November 2020 implementing Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (1), and in particular Article 32(1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 18 January 2012, the Council adopted Regulation (EU) No 36/2012. (2) In view of the gravity of the situation in Syria, and considering the recent ministerial appointments, eight persons should be added to the list of natural and legal persons, entities or bodies subject to restrictive measures in Annex II to Regulation (EU) No 36/2012. (3) Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 should therefore be amended accordingly, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Article 1 Annex II to Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 is amended as set out in the Annex to this Regulation. Article 2 This Regulation shall enter into force on the date of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. Done at Brussels, 6 November 2020. For the Council The President M. -

SYRIA: SHELTER RESPONSE SNAPSHOT Syria Hub Sheltercluster.Org Reporting Period: January - December 2016 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter

Shelter Sector SYRIA: SHELTER RESPONSE SNAPSHOT Syria Hub Sheltercluster.org Reporting Period: January - December 2016 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter ± ALEPPO TOTAL BENEFICIARIES REACHED / ASSISTED SHELTER PARTNERS Al-Ihsan DRC IOM overall People in Need (PiN) SARC STD AL-Ta’alouf 2.4 M targeted PiN / HRP 2016: RESCATE UNHCR TURKEY 115,880 1.2 M LATTAKIA SHELTER PARTNERS 39% of 300,000 targeted PiN (in shelter) by Syria Hub IOM MOLA PUI UNHCR UNRWA BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER GOVERNORATE 37,203 AL-HASAKEH 33,649 Aleppo Al-Hasakeh SHELTER PARTNERS ACF IOM SIF UNHCR Ar-Raqqa Idleb 15,970 Lattakia 8,052 5,137 5,035 TARTOUS 2,757 2,504 Deir-ez-Zor 2,150 1,993 1,430 SHELTER PARTNERS HAMA IOM MOLA PUI UNHCR Aleppo Rural Homs Dar'a Tartous Lattakia Hama Damascus Quneitra Al-Hasakeh As-Sweida Hama SHELTER PARTNERS Damascus IOM MOLA SIF UNHCR BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY TYPE OF SUPPORT Tartous DAMASCUS 23% 54% 3% 15% 5% SHELTER PARTNERS HOMS MOLA PUI UNHCR UNRWA Homs SHELTER PARTNERS ADRA AL-Berr Aoun AL-INSHAAT CCS DRC EMERGENCY COLLECTIVE UNRWA COLLECTIVE DURABLE WINTERIZATION LEBANON GOPA IOM MOLA SHELTER KITS SHELTERs SHELTERS SUPPORT SUPPORT PUI SARC SIF QUNEITRA UNHCR UNHABITAT SHELTER PARTNERS Damascus RIF DAMASCUS SHELTER PROJECTS PER STAGE MOLA MEDAIR UNHCR SHELTER PARTNERS ADRA DRC IOM MEDAIR IRAQ MOLA SIF STD PUI Rural Damascus UNHCR UNRWA 9% 8% 8% 74% AS-SWEIDA SHELTER PARTNERS IOM MOLA UNHCR Esal El-Ward An Nabk 14 13 12 119 Sarghaya Ma'loula Jirud LEGEND PLANNED & APPROVED PHYSICAL COMPLETE Rankus Raheiba 2016 Shelter People In Need -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC United Nations Cross-Border Operations Under UNSC Resolutions As of 31 December 2020

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC United Nations cross-border operations under UNSC resolutions As of 31 December 2020 UN Security Council Resolutions 2165/2191/2258/2332/2393/2449/2504/2533 930 14 Through the adoption of resolutions 2165 (2014),and its subsequent renewals 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 Consignments Trucks (2016), 2393 (2017), 2449 (2018), 2504 (2020) and 2533 (2020) until 10 July 2021, the UN Security Council in December 2020 in December 2020 6 has authorized UN agencies and their partners to use routes across conflict lines and the border crossings at Agencies Bab al-Salam, Bab al-Hawa, Al-Ramtha and Al Yarubiyah, to deliver humanitarian assistance, including medical reported and surgical supplies, to people in need in Syria. As of 10 July 2020, based on resolution 2533, Bab al-Hawa is 43,348 1,318 the only crossing open at this point in time. The Government of Syria is notified in advance of each shipment Trucks Consignments in December and a UN monitoring mechanism was established to oversee loading in neighboring countries and confirm the since July 2014 since July 2014 2020 humanitarian nature of consignments. Number of trucks per crossing point by month since July 2014 Number of targeted sectors by district in December 2020 Bab al-Hawa 33,376 Since Jul 2014 Bab al-Salam 5,268 Since Jul 2014 TURKEY Al-Malikeyyeh Quamishli 1,200 930 1,200 800 800 Jarablus Ain Al Arab Ras Al Ain 400 0 Afrin 400 A'zaz Tell Abiad 0 0 Bab Al Bab Al-Hasakeh al-Hawa Jul 2014 Dec 2020 Jul 2014 Dec 2020 ] Al-Hasakeh Harim Jebel Jisr- Menbij Lattakia -

Damascus & Rural Damascus, Syria: Nfi Response

NFI Sector DAMASCUS & RURAL DAMASCUS, SYRIA: NFI RESPONSE Syria Hub Reporting Period: January 2017 CORE SUPPLEMENTARY ± ITEMS ITEMS TOTAL BENEFICIARIES ADEQUATELY SERVED Al-Hasakeh Aleppo Ar-Raqqa Deir Attiyeh 15,000 190,011 Homs PEOPLE WHO RECEIVED MORE THAN 4 CORE NFI PEOPLE WHO RECEIVED AT LEAST 1 SUPPLEMENTA- Idleb ITEMS (.75% OF THE 2.0M PEOPLE IN NEED IN RY ITEM WHICH INCLUDES SEASONAL ITEMS (10% Lattakia DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES) OF THE 2.0M PEOPLE IN NEED IN DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES) Hama Deir-ez-Zor TOTAL BENEFICIARIES PER SUB-DISTRICT Tartous An Nabk QATANA 7,500 DAMASCUSE 44,090 Yabroud GHIZLANIYYEH 7,500 KISWEH 28,500 DAMASCUS & RURAL-DAMASCUSHoms JARAMANA 23,750 Esal El-Ward QATANA 18,750 AT-TALL 17,500 Jirud GHIZLANIYYEH 15,417 AZ-ZABDANI 12,500 Damascus Rural Damascus Ma'loula SAHNAYA 11,250 Sarghaya DARIYA 10,000 Quneitra Rankus Raheiba DIMAS 8,255 Dar'a As-Sweida BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY TYPE OF SUPPORT Az-Zabdani Madaya Al Qutayfah ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS Sidnaya INSIDE DAMASCUS AND RURAL Breakdown of 2 million people 29K DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES WHO 174K in need of NFIs in Damascus RECEIVED IN-KIND ASSISTANCE FROM At Tall IN-KIND ASSISTANCE and Rural Damascus Ein Elfijeh REGULAR PROGRAMMES OF THE IN-KIND ASSISTANCE SECTOR in 2017 per sub-district Qudsiya ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS 6K 0 - 20,000 Dimas Duma 3K FROM HARD-TO-REACH AND LEBANON BESEIGED AREAS WHO RECEIVED Harasta INTER-AGENCY CONVOY IN-KIND ASSISTANCE THROUGH INTER-AGENCY CONVOY 20,001 - 60,000 INTER-AGENCY CONVOY Damascus Arbin 60,001 - 124,200 DamascusKafr Batna Rural Damascus 9K Jaramana Nashabiyeh 0 ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS 124,201 - 190,000 WHO RECEIVED CASH ASSISTANCE CASH SUPPORT FROM UNRWA CASH SUPPORT Qatana Markaz Darayya 190,001 - 701,000 Maliha NOTE: Breakdown of beneficiaries per type of support does not necessarily sum up to the reported number of beneficiaries as some communities may have received more than one type of assistance. -

State-Led Urban Development in Syria and the Prospects for Effective Post-Conflict Reconstruction

5 State-led urban development in Syria and the prospects for effective post-conflict reconstruction NADINE ALMANASFI As the militarized phase of the Syrian Uprising and Civil War winds down, questions surrounding how destroyed cities and towns will be rebuilt, with what funding and by whom pervade the political discourse on Syria. There have been concerns that if the international community engages with reconstruction ef- forts they are legitimizing the regime and its war crimes, leaving the regime in a position to control and benefit from reconstruc- tion. Acting Assistant Secretary of State of the United States, Ambassador David Satterfield stated that until a political process is in place that ensures the Syrian people are able to choose a leadership ‘without Assad at its helm’, then the United States will not be funding reconstruction projects.1 The Ambassador of France to the United Nations also stated that France will not be taking part in any reconstruction process ‘unless a political transition is effectively carried out’ and this is also the position of the European Union.1 Bashar al-Assad him- self has outrightly claimed that the West will have no part to play 1 Beals, E (2018). Assad’s Reconstruction Agenda Isn’t Waiting for Peace. Neither Should Ours. Available: https://tcf.org/content/report/assads-recon- struction-agenda-isnt-waiting-peace-neither/?agreed=1. 1 Irish, J & Bayoumy, Y. (2017). Anti-Assad nations say no to Syria recon- struction until political process on track. Available: https://uk.reu- ters.com/article/uk-un-assembly-syria/anti-assad-nations-say-no-to-syria- reconstruction-until-political-process-on-track-idUKKCN1BU04J. -

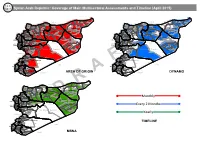

Monthly Every 2 Months Yearly

Syrian Arab Republic: Coverage of Main Multisectoral Assessments and Timeline (April 2015) Al-Malikeyyeh Al-Malikeyyeh Turkey Turkey Quamishli Quamishli Jarablus Jarablus Ras Al Ain Ras Al Ain Afrin Ain Al Arab Afrin Ain Al Arab Azaz Tell Abiad Azaz Tell Abiad Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al-Hasakeh Harim Harim Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Menbij Menbij Aleppo Aleppo Ar-Raqqa Idleb Ar-Raqqa Idleb Jisr-Ash-Shugur Jisr-Ash-Shugur As-Safira Ariha As-Safira Lattakia Ariha Ath-Thawrah Lattakia Ath-Thawrah Al-Haffa Idleb Al-Haffa Idleb Deir-ez-Zor Al Mara Deir-ez-Zor Al-Qardaha Al Mara Al-Qardaha As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia Jablah Jablah Muhradah Muhradah As-Salamiyeh As-Salamiyeh Hama Hama Banyas Banyas Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Tartous Tartous Dreikish Al Mayadin Dreikish Ar-Rastan Al Mayadin Ar-Rastan Tartous TartousSafita Al Makhrim Safita Al Makhrim Tall Kalakh Tall Kalakh Homs Syrian Arab Republic Homs Syrian Arab Republic Al-Qusayr Al-Qusayr Abu Kamal Abu Kamal Tadmor Tadmor Homs Homs Lebanon Lebanon An Nabk An Nabk Yabroud Yabroud Al Qutayfah Al Qutayfah Az-Zabdani Az-Zabdani At Tall At Tall Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Damascus Damascus Darayya Darayya Duma Duma Qatana Qatana Rural Damascus Rural Damascus IraqIraq IraqIraq Quneitra As-Sanamayn Quneitra As-Sanamayn Dar'a Quneitra Dar'a Quneitra Shahba Shahba Al Fiq Izra Al Fiq Izra As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida Dara Jordan AREA OF ORIGIN Dara Jordan