Impeach Brent Benjamin Now!? Giving Adequate Attention to Failings of Judicial Impartiality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRIP Snap Poll XII January 2020 Introduction

TRIP Snap Poll XII January 2020 Teaching, Research & International Policy (TRIP) Project Global Research Institute (GRI) https://trip.wm.edu/home Principal Investigators: Susan Peterson, William & Mary Ryan Powers, University of Georgia Michael J. Tierney, William & Mary Data Contacts: Eric Parajon or Emily Jackson Phone: (757) 221-1466 Email: i [email protected] Methodology: We attempted to contact all international relations (IR) scholars in the U.S. We define IR scholars as individuals who are employed at a college or university in a political science department or professional school and who teach or conduct research on issues that cross international borders. Of the 4,752 scholars across the U.S. that we contacted, 971 responded. The resulting response rate is approximately 20.43 percent. The poll was open 10/30/2019-12/14/2019. Our sample is roughly similar to the broader International Relations scholar population in terms of gender, academic rank and university type. Our sample includes a higher percentage of men and a higher percentage of tenured and tenure track faculty than the overall scholar population. Introduction By Emily Jackson, Eric Parajon, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney We are pleased to share the results of the 12th Teaching, Research and International Policy (TRIP) Snap Poll, fielded with the support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Our polls provide real-time data in the wake of significant policy proposals, during international crises, and on emerging foreign policy debates. In this poll, we asked questions on the 2020 Presidential Election, President Trump’s foreign policy actions, and impeachment. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION SENATE—Wednesday, December 7, 2011 The Senate met at 11:30 a.m. and was appoint the Honorable KIRSTEN E. GILLI- day and the hundreds of thousands called to order by the Honorable BRAND, a Senator from the State of New more who made the ultimate sacrifice KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, a Senator from York, to perform the duties of the Chair. during World War II. These service- the State of New York. DANIEL K. INOUYE, members are heroes. They set a fine ex- President pro tempore. ample for the men and women who pro- PRAYER Mrs. GILLIBRAND thereupon as- tect our freedoms today, and none of us sumed the chair as Acting President The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- will ever forget their courage. pro tempore. fered the following prayer: Let us pray. f f O mighty God, our hope for years to RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY PAYROLL TAX CUT come, thank You for giving us this day LEADER to use for Your glory. From the morn- Mr. REID. Madam President, the Re- ing Sun until the going down of the The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- publicans like to claim they are the same, Your blessings provide us with pore. The majority leader is recog- party of the tax cuts, but as Democrats confidence that our future is brighter nized. propose more tax relief—we propose it than our past. f every day for working families—Repub- Today, as we remember Pearl Harbor licans every day are showing their true SCHEDULE and a day of infamy, we praise You for colors. -

Extensions of Remarks E1015 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

May 19, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1015 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE COURTS THWART THE EPA'S doing nothing at all and shutting down an CONGRATULATING THE MEN'S POWER GRAB industry. The governing case (Lead Indus- VOLLEYBALL TEAM OF BYU tries Association v. EPA) gave the EPA this broad power because it was issued by the HON. MICHAEL G. OXLEY D.C. Circuit five days before the Supreme HON. CHRIS CANNON OF OHIO Court's benzene decision, and thus was unaf- OF UTAH IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES fected by the latter ruling. But it was only a IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES matter of time before the EPA's power would Wednesday, May 19, 1999 collide with the Supreme Court's limita- Wednesday, May 19, 1999 Mr. OXLEY. Mr. Speaker, many of us tions. Mr. CANNON. Mr. Speaker, on May 8, 1999 voiced serious concern when the U.S. Envi- For those subject to the EPA's unchecked in Los Angeles, Brigham Young University ronmental Protection Agency approved strict authority, the day of reckoning came none won its first-ever NCAA men's volleyball title in new NAAQs standards affecting ozone and too soon. EPA issued these rules in July 1997 despite: their first-ever NCAA Tournament appearance. particulate matter levels. We warned that EPA They finished the season with a record of 30± was not basing the standards on good Its science advisory board's admonition that the new ozone rule did not deal with 1, suffering their only loss to Long Beach science, and indeed questioned whether the any new significant risk not already ad- State whom they beat in the finals. -

International Child Abduction: Implementa- Tion of the Hague Convention on Civil Aspects of International Child Abduc- Tion

INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUCTION: IMPLEMENTA- TION OF THE HAGUE CONVENTION ON CIVIL ASPECTS OF INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUC- TION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Thursday, October 14, 1999 Serial No. 106±89 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63±699 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 12:44 Jul 17, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 63699.TXT HINTREL1 PsN: HINTREL1 COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York, Chairman WILLIAM F. GOODLING, Pennsylvania SAM GEJDENSON, Connecticut JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois HOWARD L. BERMAN, California DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California MATTHEW G. MARTINEZ, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey CASS BALLENGER, North Carolina ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois CYNTHIA A. MCKINNEY, Georgia EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida PETER T. KING, New York PAT DANNER, Missouri STEVE CHABOT, Ohio EARL F. HILLIARD, Alabama MARSHALL ``MARK'' SANFORD, South BRAD SHERMAN, California Carolina ROBERT WEXLER, Florida MATT SALMON, Arizona STEVEN R. ROTHMAN, New Jersey AMO HOUGHTON, New York JIM DAVIS, Florida TOM CAMPBELL, California EARL POMEROY, North Dakota JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts KEVIN BRADY, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BARBARA LEE, California PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York GEORGE RADANOVICH, California JOSEPH M. -

Giving Adequate Attention to Failings of Judicial Impartiality

Impeach Brent Benjamin Now!? Giving Adequate Attention to Failings of Judicial Impartiality JEFFREY W. STEMPEL* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION:M EN WITH NO REGRETS AND INADEQUATE CONCERN................... 2 II. CAPERTON V. MASSEY: JUDICIAL ERROR; WASTED RESOURCES; NEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW—AND LIGHT TREATMENT OF THE PERPETRATOR ............................................................................................... 10 A. The Underlying Action............................................................................... 10 B. The 2004 West Virginia Supreme Court Elections..................................... 12 C. Review and Recusal ................................................................................... 13 D. The Supreme Court Intervenes .................................................................. 16 E. Caperton’s Test for Determining When Recusal Is Required by the Due Process Clause ........................................................................ 17 F. Comparing the “Reasonable Question as to Impartiality” Standard for Nonconstitutional Recusal Under Federal and State Law to the “Serious Risk of Bias” Standard for Constitutional Due Process Under Caperton....................................... 19 G. The Dissenters’ Defense of Justice Benjamin—And Defective Judging ...................................................................................... 25 H. Enablers: Reluctance To Criticize Justice Benjamin................................. 28 * © 2010 Jeffrey W. Stempel. Doris S. & Theodore B. Lee Professor -

106Th Congress 239

SOUTH CAROLINA 106th Congress 239 SOUTH CAROLINA (Population 1998, 3,836,000) SENATORS STROM THURMOND, Republican, of Aiken, SC; attorney and educator; committees: chair- man, Senate Armed Services Committee; ranking member, Judiciary; senior member, Veterans' Affairs. Family: born December 5, 1902, in Edgefield, SC; son of John William and Eleanor Gertrude (Strom) Thurmond; married Jean Crouch, 1947 (deceased January 6, 1960); married Nancy Moore, 1968; four children: Nancy Moore (deceased April 14, 1993), James Strom II, Juliana Gertrude, and Paul Reynolds. Education: 1923 graduate of Clemson University; studied law at night under his father, admitted to South Carolina bar, 1930, and admitted to practice in all federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. Professional career: teacher and athletic coach (1923±29), county superintendent of education (1929±33), city attorney and county attor- ney (1930±38), State Senator (1933±38), circuit judge (1938±46), Governor of South Carolina (1947±51), serving as chairman of Southern Governors Conference (1950); practiced law in Edgefield, SC (1930±38) and in Aiken, SC (1951±55); adjunct professor of political science at Clemson University and distinguished lecturer at the Strom Thurmond Institute; member, President's Commission on Organized Crime and Commission on the Bicentennial of the Con- stitution. Military service: Reserve officer for 36 years; while serving as judge, volunteered for active duty in World War II the day war was declared against Germany; served with Head- quarters First Army (1942±46), American, European, and Pacific theaters; participated in Nor- mandy invasion with 82nd Airborne Division and landed on D-day; awarded 5 battle stars and 18 decorations, medals, and awards, including the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, Bronze Star Medal with ``V'', Purple Heart, Belgian Order of the Crown, and French Croix de Guerre; major general, U.S. -

Monmouth University Poll NORTH CAROLINA: COOPER LEADS for GUV, TIGHT SENATE RACE, PREZ in PLAY

Please attribute this information to: Monmouth University Poll West Long Branch, NJ 07764 www.monmouth.edu/polling Follow on Twitter: @MonmouthPoll _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Released: Contact: Thursday, September 3, 2020 PATRICK MURRAY 732-979-6769 (cell); 732-263-5858 (office) [email protected] Follow on Twitter: @PollsterPatrick NORTH CAROLINA: COOPER LEADS FOR GUV, TIGHT SENATE RACE, PREZ IN PLAY West Long Branch, NJ – Joe Biden and Donald Trump are separated by a negligible 2-point margin among all registered voters in North Carolina according to the Monmouth (“Mon-muth”) University Poll, while the U.S. Senate race is even tighter. Gov. Roy Cooper, on the other hand, currently enjoys a large lead in his reelection bid on the back of strong voter approval of his handling of the Covid- 19 crisis. Among all registered voters in North Carolina, the race for president stands at 47% for Biden and 45% for Trump. Another 3% support Jo Jorgensen (Libertarian), less than 1% back either Howie Hawkins (Green) or Don Blankenship (Constitution), and 3% are undecided. Voter intent includes 41% who say they are certain to vote for Biden (versus 44% who say they are not at all likely to support the Democrat) and 40% who are certain to support Trump (versus 47% who are not at all likely). Under a likely voter scenario with a somewhat higher level of turnout than 2016, Biden stands at 48% support and Trump is at 46%. The results are an identical 48% to 46% when using a likely voter model with lower turnout. Each of the last three presidential elections were decided by fewer than four percentage points in North Carolina. -

February 10, 2020 Kerri Kupec Director, Office of Public Affairs U.S

February 10, 2020 Kerri Kupec Director, Office of Public Affairs U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 Re: Request for Expedition of Freedom of Information Act Request Dear Ms. Kupec; Pursuant to Department of Justice (“DOJ”) regulations, 28 C.F.R. § 16.5(e)(2), Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (“CREW”) requests that you authorize the expedition of a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request CREW made today to the Executive Office for United States Attorneys. I have enclosed a copy of this request. The FOIA request seeks copies of all records of communications between President Trump, White House employees, or personal attorneys to President Trump and the Department of Justice regarding investigations, requests for investigations, or other inquiries concerning concerning the family members, campaign committees, campaign staff, or businesses of past and current candidates for president in the 2020 election. The term “past and current candidates for president in the 2020 election” means Michael Bennet, Joe Biden, Michael Bloomberg, Cory Booker, Steve Bullock, Pete Buttigieg, Julian Castro, Bill De Blasio, Roque De La Fuente, John Delaney, Tulsi Gabbard, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, John Hickenlooper, Jay Inslee, Amy Klobuchar, Wayne Meesam, Seth Moulton, Richard Ojeda, Beto O’Rourke, Deval Patrick, Tim Ryan, Bernie Sanders, Mark Sanford, Joe Sestak, Tom Steyer, Eric Swalwell, Joe Walsh, Elizabeth Warren, William (Bill) F. Weld, Marianne Williamson, and Andrew Yang. CREW has requested that DOJ search the records of the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, including but not limited to the Office of United States Attorney for the District of Connecticut John H. -

Union Calendar No. 881

1 Union Calendar No. 881 115TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 115–1114 ACTIVITIES OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2019 (Pursuant to House Rule XI, 1(d)(1)) Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdys.gov http://oversight.house.gov/ JANUARY 2, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–945 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:03 Jan 08, 2019 Jkt 033945 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR1114.XXX HR1114 SSpencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM TREY GOWDY, South Carolina, Chairman JOHN DUNCAN, Tennessee ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DARRELL ISSA, California CAROLYN MALONEY, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK SANFORD, South Carolina Columbia JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan WILLIAM LACY CLAY, Missouri PAUL GOSAR, Arizona STEPHEN LYNCH, Massachusetts SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee JIM COOPER, Tennessee VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ROBIN KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDA LAWRENCE, Michigan DENNIS ROSS, Florida BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey MARK WALKER, North Carolina RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois ROD BLUM, Iowa JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland JODY B. HICE, Georgia JIMMY GOMEZ, California STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma PETER WELCH, Vermont GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin MATT CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania -

Potential Impacts of Proposed Changes to the Clean Water Act Jurisdictional Rule Hearing Committee on Transportation and Infrast

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE CLEAN WATER ACT JURISDICTIONAL RULE (113–73) HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON WATER RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 11, 2014 Printed for the use of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure ( Available online at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/ committee.action?chamber=house&committee=transportation U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 88–239 PDF WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 12:12 Jan 29, 2015 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 P:\HEARINGS\113\WR\6-11-1~1\88239.TXT JEAN COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska NICK J. RAHALL, II, West Virginia THOMAS E. PETRI, Wisconsin PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee, Columbia Vice Chair JERROLD NADLER, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida CORRINE BROWN, Florida FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas GARY G. MILLER, California ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland SAM GRAVES, Missouri RICK LARSEN, Washington SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan TIMOTHY H. BISHOP, New York DUNCAN HUNTER, California MICHAEL H. MICHAUD, Maine ERIC A. ‘‘RICK’’ CRAWFORD, Arkansas GRACE F. NAPOLITANO, California LOU BARLETTA, Pennsylvania DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas TIMOTHY J. -

General 2020

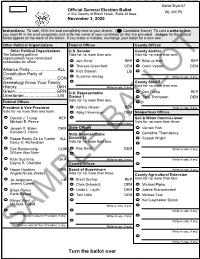

11 Ballot Style 67 Official General Election Ballot Pct. Off. Initials WL W4 P6 in the County of Black Hawk, State of Iowa November 3, 2020 21 Instructions: To vote, fill in the oval completely next to your choice. ( Candidate Name) To cast a write-in vote, you must fill in the oval completely and write the name of your candidate on the line provided. Judges for the judicial ballot appear on the back of the ballot. If you make a mistake, exchange your ballot for a new one. Other Political Organizations Federal Offices County Offices Other Political Organizations U.S. Senator County Auditor The following political Vote for no more than one. Vote for no more than one. organizations have nominated candidates for office: Joni Ernst REP Billie Jo Heth REP Theresa Greenfield DEM Grant Veeder DEM Alliance Party.......................ALL Rick Stewart LIB Constitution Party of 40 Iowa.....................................CON Suzanne Herzog Write-in vote, if any. 41 Genealogy Know Your Family County Sheriff Vote for no more than one. History.................................GKH Write-in vote, if any. Green..................................GRN U.S. Representative Dan Trelka REP 44 Libertarian............................LIB District 1 Tony Thompson DEM Federal Offices Vote for no more than one. President & Vice President Ashley Hinson REP Write-in vote, if any. Vote for no more than one team. Abby Finkenauer DEM Nonpartisan Offices 48 Donald J. Trump REP Soil & Water Commissioner Michael R. Pence Write-in vote, if any. Vote for no more than three. Joseph R. Biden DEM State Offices Vernon Fish Kamala D. Harris State Representative Geraldine Thornsberry 53 BALLOT Roque Rocky De La Fuente ALL District 62 Russell Wright Darcy G. -

08/24/2020 Page 1 of 9 Official List Candidates for President For

08/24/2020 Official List Page 1 of 9 Candidates for President For GENERAL ELECTION 11/03/2020 Election, * denotes incumbent Name Address Party County Slogan DONALD J. TRUMP * P.O. BOX 13570 Republican ARLINGTON, VA 22219 08/24/2020 Official List Page 2 of 9 Candidates for President For GENERAL ELECTION 11/03/2020 Election, * denotes incumbent Name Address Party County Slogan JOSEPH R. BIDEN P.O. BOX 58174 Democratic PHILADELPHIA, PA 19120 08/24/2020 Official List Page 3 of 9 Candidates for President For GENERAL ELECTION 11/03/2020 Election, * denotes incumbent Name Address Party County Slogan DON BLANKENSHIP 118 CRYSTAL ACRES CONSTITUTION PARTY ( VICE PRESIDENT WILLIAM SPRIGG, WV 25678 MOHR) ATLANTIC CONSTITUTION PARTY BERGEN CONSTITUTION PARTY BURLINGTON CONSTITUTION PARTY CAMDEN CONSTITUTION PARTY CAPE MAY CONSTITUTION PARTY CUMBERLAND CONSTITUTION PARTY ESSEX CONSTITUTION PARTY GLOUCESTER CONSTITUTION PARTY HUDSON CONSTITUTION PARTY HUNTERDON CONSTITUTION PARTY MERCER CONSTITUTION PARTY MIDDLESEX CONSTITUTION PARTY MONMOUTH CONSTITUTION PARTY MORRIS CONSTITUTION PARTY OCEAN CONSTITUTION PARTY PASSAIC CONSTITUTION PARTY SALEM CONSTITUTION PARTY SOMERSET CONSTITUTION PARTY SUSSEX CONSTITUTION PARTY UNION CONSTITUTION PARTY WARREN CONSTITUTION PARTY 08/24/2020 Official List Page 4 of 9 Candidates for President For GENERAL ELECTION 11/03/2020 Election, * denotes incumbent Name Address Party County Slogan ROQUE "ROCKY" DE LA 5440 MOREHOUSE DRIVE Apt- ALLIANCE PARTY FUENTE Unit 4000 ( VICE PRESIDENT DARCY G. SAN DIEGO, CA 92121 RICHARDSON)