Bchn 1980 Spring.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Year Ended 31 January 2008 (10 Months)

2008 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 JANUARY 2008 (10 MONTHS) Boys & Girls Club Services of Greater Victoria EVENTS & HAPPENINGS PRESIDENT’S REPORT In Ralph’s absence, Ellie Sears continues to astound us with their James took over hosting 2007 was a shortened fiscal year as we changed program in 2001. And speaking of congratu- generous support! They hosted four BBQs in the Pancake Breakfast to the summer of 2007, supported the officially kick-off our our year end to accommodate logistics within lations, our children were very excited to Children’s Carnival with lots of great prizes, internal United Way our accounting department. Despite this follow Hamilton Boys & Girls Club alumni donated a Broil King BBQ as part of a live Campaign. Below Alan shortened reporting period, the ten months Brain Melo who won the Canadian Idol auction item for the Boat for Hope event and Perry and Jim Tighe enjoy covered in this report were filled with many contest! the list goes on! Round It Off days breakfast with Andrea happen throughout the year as do celebrations as well as on-going challenges and Martin and Kate Mansell. Other notable events included our participa- their sale of special plush items, Alan and Jim were on opportunities. In preparing our commentaries like Elvin the Elf pictured here. We hand to make their Ralph and I have opted to address each of tion again in the Pink Salmon Festival; received $11,600 in cash, presentation. these two themes in our respective reports. Harbourside hosted an entertaining family sponsorship, and in-kind gifts last pumpkin carving event; Youth Leaders from year – we can never say thank you However, both reviews should be read as two enough to this wonderful sections of the same report. -

Mystic Spring"

THE CONFUSING LEGEND OF THE "MYSTIC SPRING" by Grant Keddie, Royal B.C. Museum, 2003 In the municipality of Oak Bay, above the western side of Cadboro Bay, part of the uplands drain through a deep ravine now referred to as Mystic Vale. The creek that flows through this vale, or valley, has never been given a legal name but is referred to locally as Mystic Creek or Hobbs Creek. Mystic Creek flows north of Vista Bay Road and between Bermuda Street and Killarney road to the north of Cadboro Bay road. South of Cadboro Bay road the creek flows on the east side of Killarney road. Recently its south end was diverted east to Sinclair road. Mystic Vale is located at the far left of this photograph taken in the early 1900s. RBCM A-02978. To the west of Killarney road is Mystic Lane. Artificial duck ponds have been created above and below this lane. The area between Killarney road and the hill slope below Hibbens Close receives its surface and underground water supply from some of the uplands west of Mystic vale. House and yard construction projects in the 1930's and especially the development of the Cadboro Bay Auto court property in the 1940's disrupted the flow and configuration of two small creeks in this area. Three large ponds were dug in the 1940's to contain the flow of one of the creeks. Later, landfill and house construction altered this area substantially. The present artificial duck pond along Waring road is a remnant of one of these earlier water control ponds. -

The Blurb 2102-355 Anfield Rd

DISTRICT 19-I DISTRICT 19-I CABINET: District Governor Joyce L. Boyle (Everett) The Blurb 2102-355 Anfield Rd. Courtenay, BC V9N 0C6 250-871-1900 EDITION #6, DECEMBER, 2017 [email protected] www.lionsdistrict19-I.org Past District Governor Alan Guy (Janet) Message from 19-I’s 502 Arbutus Dr. Mayne Island, BC V0N 2J1 District Governor Joyce Boyle 250-539-9876 [email protected] 1st Vice District Governor Mike Dukes (Karen) 63 Vista Dr. Sekiu, WA 98381 360-963-2287 [email protected] 2nd Vice District Governor Cec Specht (Cathy) 1450 Griffin Dr. Courtenay, BC V9N 8M6 250-338-0509 [email protected] Cabinet Secretary PDG Leslie Smith (Burnie) 6626 Everest Dr. Nanaimo, BC V9T 6H6 250-390-0730 [email protected] Cabinet Treasurer PDG John Higgs (Loni) 7-897 Admirals Rd. Victoria, BC V9A 2P1 250-995-9288 [email protected] For so many people, Lions make these words have real meaning! So many Christmases have Joy attached because of our dona- STAYING CONNECTED: tions. The results from the work we do in our communities is so IT CHAIR: eventful at this time of year. PDG Ron Metcalfe & team lions19i.ca And now is also the time for all of you to enjoy time with your FACEBOOK page: own families and friends and soak up all the love that is available District 19-I for current to you. We all know we cannot give what we do not have, so lap happenings & more. (ZC Bob Orchard: it up! [email protected] PUBLIC RELATIONS: I have so enjoyed my visitations to all the Clubs so far this year PDG Brian Phillips and look forward to some time off myself too in December, and 250-642-2408 then back “On the Road Again” in the new year. -

The Corporation of the District of Central Saanich Public Hearing- 6:00 Pm

THE CORPORATION OF THE DISTRICT OF CENTRAL SAANICH PUBLIC HEARING- 6:00 PM Monday, March 26, 2018 Council Chambers (Please note that all proceedings of Public Hearings are video recorded) AGENDA 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. OPENING STATEMENT BY MAYOR 2.1. Opening Statement by the Mayor Pg. 3 - 4 3. CENTRAL SAANICH LAND USE BYLAW AMENDMENT BYLAW NO. 1935, 2018 3.1. Central Saanich Land Use Bylaw Amendment Bylaw No. 1935, 2018 Pg. 5 - 7 (A Bylaw to Amend the Land Use Bylaw - Cannabis Production) 3.2. Notice of Public Hearing Pg. 8 3.3. Background Reports, Committee / Council Minutes and Correspondence Pg. 9 - 65 Received: • Report from the Director of Planning and Building Services dated February 2, 2018 [Previously presented at the February 13, 2018 Committee of the Whole Meeting] • Excerpts from the Minutes of the February 13, 2018 Committee of the Whole and February 19, 2018 Regular Council Meetings • Correspondence Received Prior to Introduction of Bylaw No. 1935, 2018 and Publication of Notice of Public Hearing: • Ray, J - Jan 5, 2018 • Williams, D - Jan 8, 2018 • Burkhardt, A - Jan 9, 2018 • Horie, H - January 9, 2018 • Bond, D - Jan 10, 2018 • Kokkelink, G - January 11, 2018 • Chapman, N - Jan 11, 2018 • Robichaud, M - Jan 11, 2018 • Robertson, C - January 12, 2018 • Wolfson, K & G - January 17, 2018 • Fulton, D - January 18, 2018 • Box, A - January 19, 2018 • Russell, S - January 20, 2018 • Wolfson, K & G - January 20, 2018 • Buicliu, I - January 21, 2018 • Nelson, J - January 28, 2018 • Correspondence Received Subsequent to Introduction of Bylaw No. 1935, 2018 and Publication of Notice of Public Hearing: • Misovich, M - February 19, 2018 • Agricultural Land Reserve - February 22, 2018 • Fulton, D - March 21, 2018 • Epp, D & N - March 21, 2018 3.4. -

Gordon Head Is Bordered on the North and East by Haro Strait, on the West by Blenkinsop Valley and Mount Douglas, and on the South by Mckenzie Avenue

Geoffrey Vantreight with First Nations workers on the Vantreight strawberry farm, 1910 (1984-012-006) Gordon Head is bordered on the north and east by Haro Strait, on the west by Blenkinsop Valley and Mount Douglas, and on the south by McKenzie Avenue. It was a heavily forested wilderness when it was first settled by farmers, starting with James Tod (Todd) in 1852. By the 1870s, thirteen men, including Charles Dodd, Michael Finnerty, and John Work, owned all of the land identified as Gordon Head. The area became famous for its strawberries, which sold for high prices until 1914 when the dropping value of the crop led to the formation of the Saanich Fruit Growers’ Association. By 1945 the strawberry crop was declining in importance and daffodils became an important cash crop. Starting in 1902, Arbutus Cove was favoured as an area of summer homes for prominent Victoria-area families. In 1921, city water service was brought to Gordon Head leading to a proliferation of greenhouses and vegetable growers. Since the 1950s, the area has gradually been developed with single-family housing, facilitated through the introduction of sewers in the late 1960s. Produced by Saanich Archives, December 2020 Saanich Official Community Plan 2008, Map 22 Local Areas The District of Saanich lies within the traditional territories of the Ləkʷəŋən̓ and SENĆOŦEN speaking peoples. Evidence of First Nations settlement in the area now called Saanich dates back over 4,000 years. The Ləkʷəŋən̓ peoples are made up of two nations, the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations and the W̱ SÁNEĆ peoples are made up of five nations, W̱ JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip), BOḰEĆEN (Pauquachin), SȾÁUTW̱ (Tsawout), W̱ SIḴEM (Tseycum) and MÁLEXEȽ (Malahat) Nations. -

REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING HELD in the GEORGE FRASER ROOM, 500 MATTERSON DRIVE Tuesday, February 13, 2018 at 7:30 PM

REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL Tuesday, February 27, 2018 @ 7:30 PM George Fraser Room, Ucluelet Community Centre, 500 Matterson Drive, Ucluelet AGENDA Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FIRST NATIONS TERRITORY _ 2.1. Council would like to acknowledge the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ First Nations on whose traditional territories the District of Ucluelet operates. 3. ADDITIONS TO AGENDA 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 4.1. February 13, 2018 Regular Minutes 5 - 14 2018-02-13 Regular Minutes 5. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 6. MAYOR’S ANNOUNCEMENTS 7. PUBLIC INPUT, DELEGATIONS & PETITIONS 7.1 Public Input 7.2 Delegations • Markus Knab, Mary Wanna Café 15 Re: Dispensary License D-1 Knab Delegation 8. CORRESPONDENCE 8.1. Pacific Dialogue Forums Invitation 17 - 20 Yvette Myers, Ocean Protection Plan C-1 OPP Invitation 8.2. Financial Request for the WildSafeBC Community Coordinator 21 Todd Windle, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve C-2 PRNP Letter 9. INFORMATION ITEMS 9.1. Appreciation Letter 23 Jen Rashleigh & Morgan Reid Page 2 of 134 I-1 Rashleigh & Reid Letter 9.2. Affordable Housing 25 - 26 The City of Victoria I-2 Victoria Letter to Minister Robinson 9.3. Welcome Letter 27 - 28 Federation of Canadian Municipalities I-3 FCM Welcome Letter 9.4. Supporting BC Aquaculture 29 - 31 Ken Roberts, Creative Salmon I-4 Creative Salmon Letter 9.5. Marihuana Addiction Treatment, Prevention and Education Resolution 33 - 34 Mayor Alice Finall, District of North Saanich I-5 North Saanich Letter 10. COUNCIL COMMITTEE REPORTS 10.1 Councillor Sally Mole Deputy Mayor April – June • Ucluelet -

REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING HELD in the GEORGE FRASER ROOM, 500 MATTERSON DRIVE Tuesday, October 8, 2019 at 2:30 PM

REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL Tuesday, October 22, 2019 @ 2:30 PM George Fraser Room, Ucluelet Community Centre, 500 Matterson Drive, Ucluelet AGENDA Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FIRST NATIONS TERRITORY _ Council would like to acknowledge the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ First Nations on whose traditional territories the District of Ucluelet operates. 3. NOTICE OF VIDEO RECORDING Council would like to advise District of Ucluelet Staff, audience members and delegates that this Council proceeding is being video recorded and the recording will be live streamed or subsequently published on the District of Ucluelet's YouTube channel. 4. ADDITIONS TO AGENDA 5. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 6. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 6.1. October 8, 2019 Regular Minutes 5 - 17 2019-10-08 Regular Minutes 7. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 8. MAYOR’S ANNOUNCEMENTS 8.1. Presentation of the Sovereign's Medal for Volunteers to Mary Kimoto 9. PUBLIC INPUT, DELEGATIONS & PETITIONS 9.1 Public Input 9.2 Delegations • Sergeant Steve Mancini, RCMP Re: RCMP Update 10. CORRESPONDENCE 10.1. Request for Letter of Support - Ellen Kimoto 19 - 20 Barb Gudbranson, President, Ucluelet & Area Historical Society C-1 Ucluelet Area Historical Society Letter of Support 10.2. Community Child Care Space Creation Program and Community Child Care 21 Page 2 of 72 Planning Grant Program Honourable Scott Fraser, MLA (Mid Island-Pacific Rim) C-2 Child Care Grant 11. INFORMATION ITEMS 11.1. BC Hydro Community Relations 2019 Annual Report - Vancouver Island- 23 - 36 Sunshine Coast Ted Olynyk, Community Relations Manager, Vancouver Island-Sunshine Coast - BC Hydro I-1 BC Hydro - Annual Report 12. COUNCIL COMMITTEE REPORTS 12.1 Councillor Rachelle Cole Deputy Mayor October - December 2019 12.2 Councillor Marilyn McEwen Deputy Mayor November 2018 - March 2019 12.3 Councillor Lara Kemps Deputy Mayor April - June 2019 12.4 Councillor Jennifer Hoar Deputy Mayor July - September 2019 12.5 Mayor Mayco Noël 13. -

Regular Council

REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL Tuesday, November 24, 2020 @ 3:30 PM George Fraser Room, Ucluelet Community Centre, 500 Matterson Drive, Ucluelet AGENDA Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FIRST NATIONS TERRITORY Council would like to acknowledge the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ First Nation, on whose traditional territories the District of Ucluelet operates. 3. NOTICE OF VIDEO RECORDING Audience members and delegates are advised that this proceeding is being video recorded and broadcast on YouTube and Zoom, which may store data on foreign servers. 4. ADDITIONS TO AGENDA 5. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 6. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 6.1 October 27, 2020 Special Minutes 3 - 4 2020-10-27 Special Council 6.2 October 27, 2020 Regular Minutes 5 - 18 2020-10-27 Regular Council 6.3 November 10, 2020 Regular Minutes 19 - 26 2020-11-10 Regular Council 7. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 8. MAYOR’S ANNOUNCEMENTS 9. PUBLIC INPUT & DELEGATIONS 9.1 Public Input 9.2 Delegations • Ursula Banke, Island Work Transitions Inc (dba Alberni Valley 27 - 33 Employment Centre) Re: West Coast Labour Market Indicators Project D - U. Banke - Delegation 10. CORRESPONDENCE Page 2 of 94 10.1 Provincial Funding for Emergency / Fire Equipment for Small Communities 35 - 42 Dennis Dugas, Mayor, District of Port Hardy C - 2020-11-06 Mayor Dugas 11. INFORMATION ITEMS 11.1 Announcing the British Columbia Reconciliation Award 43 - 50 The Honourable Janet Austin, Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia and Judith Sayers, President, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council I - 2020-11-18 BC Reconciliation Award 11.2 COVID-19 Safe Restart Grants for Local Governments 51 - 53 Kaya Krishna, Deputy Minister, Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing I - 2020-11-02 Local Gov Grant 12. -

70 As Final Resting Place, Canada Is Chosen. on Citizenship Paper

70 BC STUDIES As final resting place, Canada is chosen. On citizenship paper, Signing Hand trembles. University of British Columbia COLE HARRIS Bull of the Woods, The Gordon Gibson Story, by Gordon Gibson with Carol Renison. Vancouver: Douglas and Mclntyre, 1980. Pp. 310, $16.95 hardcover. Gordon Gibson, through his own words as recorded by Renison, comes through as a racist, sexist, bullying and often insensitive man. He also emerges as a tough, often courageous, sometimes high-minded and sur prisingly honest entrepreneur. Perhaps because one senses that only such an individual could have run the risks he ran, built the mills he built and established the forest companies he did in the pioneer conditions of the 1920s to 1950s, one winces at the revelations but reads on. Too much of the book is a personal diary, written as if in the first per son, in which Gibson eulogizes himself. This is unfortunate because the events he brought about, the territory on which he imposed his will and the people whose lives he affected are exceedingly interesting to the reader who is concerned with British Columbia's history. Fewer precious revela tions and more detailed descriptions of events would have made the book a lasting tribute to the man. He is worthy of a lasting tribute, the negative characteristics notwithstanding. His version of the logging and fishing conditions and small mills in the 1920s, of boats, log-booms, storms and mishaps in dangerous seas through that decade and the next few, and, most particularly, of the establishment of Tahsis after the war are worth the reading. -

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District by Sylvia Kenny University of Victoria, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences Co-op British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Prepared for the Capital Regional District, Victoria, B.C. December 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kenny, Sylvia. Aquifers of the Capital Regional District. Cover title. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-52651 1. Aquifers - British Columbia - Capital. 2. Groundwater - British Columbia - Capital. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. II. University of Victoria (B.C.). School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. III. Capital (B.C.) IV. Title. TD227.B7K46 2004 333.91’04’0971128 C2004-960175-X Executive summary This project focussed on the delineation and classification of developed aquifers within the Capital Regional District of British Columbia (CRD). The goal was to identify and map water-bearing unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers in the region, and to classify the mapped aquifers according to the methodology outlined in the B.C. Aquifer Classification System (Kreye and Wei, 1994). The project began in summer 2003 with the mapping and classification of aquifers in Sooke, and on the Saanich Peninsula. Aquifers in the remaining portion of the CRD including Victoria, Oak Bay, Esquimalt, View Royal, District of Highlands, the Western Communities, Metchosin and Port Renfrew were mapped and classified in summer 2004. The presence of unconsolidated deposits within the CRD is attributed to glacial activity within the region over the last 20,000 years. Glacial and glaciofluvial modification of the landscape has resulted in the presence of significant water bearing deposits, formed from the sands and gravels of Capilano Sediments, Quadra and Cowichan Head Formations. -

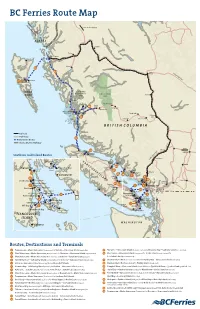

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Restorative Justice Programs in British Columbia

1 Restorative Justice Programs in British Columbia Community Accountability Programs (CAP) 2019/20 Community Program Contact Name Contact Details Webpage Abbotsford Abbotsford Restorative Justice & Advocacy Christine Bomhof Abbotsford Restorative Justice & Advocacy Association www.arjaa.org Association 105-34194 Marshall Road Abbotsford, BC V2S 5E4 T: 604-864-4844 F: 604-870-4150 E: [email protected] Armstrong/ Restorative Justice Society - North Okanagan Margaret Clark Restorative Justice Society – North Okanagan www.restorativejusticesociety.ca Spalumcheen/ 3010 – 31st Avenue Vernon, BC V1T 2G8 Lumby T: 250-550-7846 F: 250-260-5866 E: [email protected] Chilliwack Chilliwack Restorative Justice & Youth Advocacy Amanda Macpherson Chilliwack Restorative Justice & Youth Advocacy Association www.restoringjustice.ca Association 45877 Wellington Avenue Chilliwack, BC V2P 2C8 T: 604-393-3023 F: 604-393-3470 E: [email protected] Coquitlam Community Youth Justice Program Gurinder Mann Communities Embracing Restorative Action Society (CERA) www.cerasociety.org 2nd floor – 644 Poirier Street Coquitlam, BC V3J 6B1 T: 604-931-3165 F: 604-931-3176 E: [email protected] Courtenay/ Community Justice Centre Bruce Curtis Community Justice Centre of the Comox Valley Society www.communityjusticecentre.ca Comox Suite C2 – 450 8th Street Courtenay, BC V9N 1N5 T: 250-334-8101 F: 250-334-8102 E: [email protected] 2 Community Program Contact Name Contact Details Webpage Cranbrook Cranbrook & District Restorative Justice Society Doug McPhee