Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Phenomenon Electronic

Praised by Morton Feldman, courted by John Cage, bombarded with sound waves by Alvin Lucier: the unique voice of singer and composer Joan La Barbara has brought her adventures on American contemporary music’s wildest frontiers, while her own compositions and shamanistic ‘sound paintings’ place the soprano voice at the outer limits of human experience. By Julian Cowley. Photography by Mark Mahaney Electronic Joan La Barbara has been widely recognised as a so particularly identifiable with me, although they still peerless interpreter of music by major contemporary want to utilise my expertise. That’s OK. I’m willing to composers including Morton Feldman, John Cage, share my vocabulary, but I’m also willing to approach a Earle Brown, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley and her new idea and try to bring my knowledge and curiosity husband, Morton Subotnick. And she has developed to that situation, to help the composer realise herself into a genuinely distinctive composer, what she or he wants to do. In return, I’ve learnt translating rigorous explorations in the outer reaches compositional tools by apprenticing, essentially, with of the human voice into dramatic and evocative each of the composers I’ve worked with.” music. In conversation she is strikingly self-assured, Curiosity has played a consistently important role communicating something of the commitment and in La Barbara’s musical life. She was formally trained intensity of vision that have enabled her not only as a classical singer with conventional operatic roles to give definitive voice to the music of others, in view, but at the end of the 1960s her imagination but equally to establish a strong compositional was captured by unorthodox sounds emanating from identity owing no obvious debt to anyone. -

Effects of Duration of Selected Music As an Intervention on Postoperative

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 2010 Effects of duration of selected music as an intervention on postoperative pain in open-heart surgery patients during chair rest on the first postoperative day Tzu-Ting Shu Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Music Therapy Commons, and the Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Shu, Tzu-Ting, "Effects of duration of selected music as an intervention on postoperative pain in open-heart surgery patients during chair rest on the first postoperative day" (2010). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 321. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/321 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF DURATION OF SELECTED MUSIC AS AN INTERVENTION ON POSTOPERATIVE PAIN IN OPEN-HEART SURGERY PATIENTS DURING CHAIR REST ON THE FIRST POSTOPERATIVE DAY By Tzu-Ting Shu, BSN, RN Thesis Submitted to the School of Nursing College of Health and Human Services Eastern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of: MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING Thesis Committee: Lorraine M. Wilson, PhD, RN: Chair Tsu-Yin Wu, PhD, RN: Committee Member December 16, 2010 Ypsilanti, Michigan i THESIS APPROVAL Effects of Duration of Selected Music as an Intervention on Postoperative Pain in Open-heart Surgery Patients during Chair Rest on the First Postoperative Day Tzu-Ting Shu APPROVED: _________________________________ _______________________ Lorraine M. -

Theatre & Engineering a View of 9 Evenings

Eine Betrachtung von 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering A View of 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering Simone Das im Januar begonnene Projekt war ursprünglich als der ame- The project, begun in January, was to be the American Forti rikanische Beitrag zum Mitte September stattfindenden contribution to the Stockholm Festival for Art and Tech- Stockholm Festival for Art and Technology gedacht. Doch nach nology, which took place in mid-September. But by zehnmonatiger Entwicklung wurde es schließlich zur Perfor- October, after ten months of development, it emerged mancereihe 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, die im Oktober in as a series of performances called 9 Evenings: Theatre & der 69th Regiment Armory in New York gezeigt wurde, in demsel- Engineering, at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York, ben Gebäude, in dem 1913 die berühmte Armory Show stattge- the same building that housed the famous Armory Show funden hatte. Präsentiert wurden Arbeiten, die aus der Kollabo- of 1913. It showed work that had come out of a collab- ration von zehn Künstlerinnen und Künstlern und etwa dreißig oration between ten artists and about thirty engineers, Ingenieuren, die meisten von den Bell Telephone Laboratories, most of whom were from Bell Telephone Laboratories. entstanden waren. The Swedish organization that had invited the Amer- Die schwedische Organisation, die die amerikanische Gruppe ican group agreed to supply ten thousand US dollars for eingeladen hatte, sagte zu, 10 000 US-Dollar für die Herstellung the making of equipment and for artists’ fees and -

Garrett List

Garrett List Information Discographie Agenda des concerts Trombone, Compositeur, Instrument(s) Arrangeur, Chant Date de 1943 naissance Lieu de Phoenix, U.S.A naissance Contacts Email Envoyer un email Site web Site web dédié © Christian Deblanc Text also available in English Né à Phoenix (Arizona) Garrett LIST joue du trombone et chante depuis l'âge de sept ans. A dix-huit ans, lorsqu'il entre à l'Université;, il a déjà une vie professionnelle et pédagogique remplie, il joue autant de la musique classique que d'autres styles (jazz, pop, blues), tout en donnant des cours aux enfants. Il s'adonne aussi à la composition. En 1965, il part pour New York pour y suivre des études strictement classiques à la célèbre Juilliard School of Music. Il y rencontre le compositeur italien Luciano BERIO et le chef d'orchestre Dennis RUSSELL DAVIES avec qui il forme le Juillard Ensemble. Grâce à cet ensemble, il rencontre aussi les compositeurs Henri POUSSEUR et Pierre BOULEZ et se met à jouer leurs musiques. Il entreprend plusieurs tournées en Europe et enregistre. Après cette immersion totale dans la musique contemporaine et ces études intenses au conservatoire Juilliard, il ressent le besoin d'une autre vision de la création musicale. C'est l'époque du free jazz et New York est sous le choc de mai '68. Il découvre l'improvisation, pas seulement dans le cadre du jazz ou du blues, mais la considère comme une manière de vivre la création musicale de l'intérieur. Il rencontre alors John CAGE, Frederic RZEWSKI, LaMonte YOUNG, Rhys CHATHAM, Anthony BRAXTON, Steve LACY et devient membre du Musica Eletronica Viva, un des groupes les plus influents de la musique improvisée de l'époque. -

FSU ETD Template

Florida State University Libraries 2016 Music Therapy and Music Medicine Assessment in Mental Health and Medical Research with Children and Adolescents: An Integrative Review Dawn M. Pufahl Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MUSIC THERAPY AND MUSIC MEDICINE ASSESSMENT IN MENTAL HEALTH AND MEDICAL RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW By DAWN M. PUFAHL A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music 2016 Dawn M. Pufahl defended this thesis on April 15, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Lori F. Gooding Professor Directing Thesis Jayne M. Standley Committee Member Dianne Gregory Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ..................................................................................................................................v Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... vi 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1 -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXTENDED FROM WHAT?: TRACING THE CONSTRUCTION, FLEXIBLE MEANING, AND CULTURAL DISCOURSES OF “EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES” A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Charissa Noble March 2019 The Dissertation of Charissa Noble is approved: Professor Leta Miller, chair Professor Amy C. Beal Professor Larry Polansky Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Charissa Noble 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgements and Dedications viii Introduction to Extended Vocal Techniques: Concepts and Practices 1 Chapter One: Reading the Trace-History of “Extended Vocal Techniques” Introduction 13 The State of EVT 16 Before EVT: A Brief Note 18 History of a Construct: In Search of EVT 20 Ted Szántó (1977): EVT in the Experimental Tradition 21 István Anhalt’s Alternative Voices (1984): Collecting and Codifying EVT 28evt in Vocal Taxonomies: EVT Diversification 32 EVT in Journalism: From the Musical Fringe to the Mainstream 42 EVT and the Classical Music Framework 51 Chapter Two: Vocal Virtuosity and Score-Based EVT Composition: Cathy Berberian, Bethany Beardslee, and EVT in the Conservatory-Oriented Prestige Economy Introduction: EVT and the “Voice-as-Instrument” Concept 53 Formalism, Voice-as-Instrument, and Prestige: Understanding EVT in Avant- Garde Music 58 Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio 62 Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt 81 Conclusion: The Plight of EVT Singers in the Avant-Garde -

Anexo:Premios Y Nominaciones De Madonna 1 Anexo:Premios Y Nominaciones De Madonna

Anexo:Premios y nominaciones de Madonna 1 Anexo:Premios y nominaciones de Madonna Premios y nominaciones de Madonna interpretando «Ray of Light» durante la gira Sticky & Sweet en 2008. La canción ganó un MTV Video Music Awards por Video del año y un Grammy a mejor grabación dance. Premios y nominaciones Premio Ganados Nominaciones Total Premios 215 Nominaciones 407 Pendientes Las referencias y notas al pie Madonna es una cantante, compositora y actriz. Nació en Bay City, Michigan, el 16 de agosto de 1958, y creció en Rochester Hills, Michigan, se mudó a Nueva York en 1977 para lanzar su carrera en la danza moderna.[1] Después haber sido miembro de los grupos musicales pop Breakfast Club y Emmy, lanzó su auto-titulado álbum debut, Madonna en 1983 por Sire Records.[2] Recibió la nominación a Mejor artista nuevo en el MTV Video Music Awards (VMA) de 1984 por la canción «Borderline». Madonna fue seguido por una serie de éxitosos sencillos, de sus álbumes de estudio Like a Virgin de 1984 y True Blue en 1986, que le dieron reconocimiento mundial.[3] Madonna, se convirtió en un icono pop, empujando los límites de contenido lírico de la música popular y las imágenes de sus videos musicales, que se convirtió en un fijo en MTV.[4] En 1985, recibió una serie de nominaciones VMA por sus videos musicales y dos nominaciones en a la mejor interpretación vocal pop femenina de los premios Grammy. La revista Billboard la clasificó en lista Top Pop Artist para 1985, así como en el Top Pop Singles Artist en los próximos dos años. -

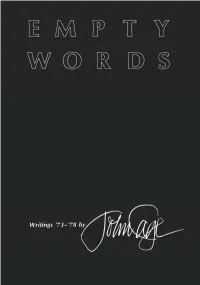

EMPTY WORDS Other

EMPTY WORDS Other Wesley an University Press books by John Cage Silence: Lectures and Writings A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings M: Writings '67-72 X: Writings 79-'82 MUSICAGE: CAGE MUSES on Words *Art*Music l-VI Anarchy p Writings 73-78 bv WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS Middletown, Connecticut Published by Wesleyan University Press Middletown, CT 06459 Copyright © 1973,1974,1975,1976,1977,1978,1979 by John Cage All rights reserved First paperback edition 1981 Printed in the United States of America 5 Most of the material in this volume has previously appeared elsewhere. "Preface to: 'Lecture on the Weather*" was published and copyright © 1976 by Henmar Press, Inc., 373 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10016. Reprint pernr~sion granted by the publisher. An earlier version of "How the Piano Came to be Prepared" was originally the Introduction to The Well-Prepared Piano, copyright © 1973 by Richard Bunger. Reprinted by permission of the author. Revised version copyright © 1979 by John Cage. "Empty Words" Part I copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Active Anthology. Part II copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Interstate 2. Part III copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Big Deal Part IV copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in WCH WAY. "Series re Morris Graves" copyright © 1974 by John Cage. See headnote for other information. "Where are We Eating? and What are We Eating? (Thirty-eight Variations on a Theme by Alison Knowles)" from Merce Cunningham, edited and with photographs and an introduction by James Klosty. -

MUSICA ELETTRONICA VIVA MEV 40 (1967–2007) 80675-2 (4Cds)

MUSICA ELETTRONICA VIVA MEV 40 (1967–2007) 80675-2 (4CDs) DISC 1 1. SpaceCraft 30:49 Akademie der Kunste, Berlin, October 5, 1967 Allan Bryant, homemade synthesizer made from electronic organ parts Alvin Curran, mbira thumb piano mounted on a ten-litre AGIP motor oil can, contact microphones, amplified trumpet, and voice Carol Plantamura, voice Frederic Rzewski, amplified glass plate with attached springs, and contact microphones, etc. Richard Teitelbaum, modular Moog synthesizer, contact microphones, voice Ivan Vandor, tenor saxophone 2. Stop the War 44:39 WBAI, New York, December 31, 1972 Frederic Rzewski, piano Alvin Curran, VCS3-Putney synthesizer, piccolo trumpet, mbira thumb piano, etc. Garrett List, trombone Gregory Reeve, percussion Richard Teitelbaum, modular Moog synthesizer Karl Berger, marimbaphone DISC 2 1. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Pt. 1 43:07 April 1982 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Serge modular synthesizer, piccolo trumpet, voice Richard Teitelbaum, PolyMoog and MicroMoog synthesizers with SYM 1 microcomputer Frederic Rzewski, piano, electronically-processed prepared piano 2. Kunstmuseum, Bern 24:37 November 16, 1990 Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Akai 6000 sampler and Midi keyboard Richard Teitelbaum, Prophet 2002 sampler, DX 7 keyboard, Macintosh computer Frederic Rzewski, piano DISC 3 1. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Pt. 2 44:05 April 1982 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Serge modular synthesizer-processing for piano and sax, piccolo trumpet, voice Richard Teitelbaum, Polymoog and MicroMoog synthesizers with SYM 1 microcomputer Frederic Rzewski, piano, electronically processed prepared piano 2. New Music America Festival 30:51 The Knitting Factory, New York, November 15, 1989 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Richard Teitelbaum, Yamaha DX 7, Prophet sampler, computer with MAX/MSP, Crackle Box Alvin Curran, Akai 5000 Sampler, MIDI keyboard, flugelhorn Frederic Rzewski, piano DISC 4 1. -

On Stockhausen's Kontakte

Document generated on 10/02/2021 2:45 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines On Stockhausen’s Kontakte (1959-60) for tape, piano and percussion A lecture/analysis by John Rea given at the University of Toronto, march 1968 Sur Kontakte de Stockhausen (1959-1960) pour bande, piano et percussions Une conférence/analyse de 1968 John Rea Stockhausen au Québec Article abstract Volume 19, Number 2, 2009 A lecture/analysis given by John Rea at the University of Toronto, March 1968, discusses various topics in the composition such as: concepts (performance URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037453ar time, production time, subjective perception of time, moment time, moment DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037453ar characteristics), discussion of particular Moments, hardware, overall formal organization, definition of structure, parameter of space (an example), See table of contents temporal transformation, and performance practice. The lecture text is also notable for the fact that Rea spoke to the pianist who had premiered Kontakte, David Tudor, who was in Toronto at that time to participate in a four and a half hour ‘happening’ known as Reunion (on March 5, 1968) organized by John Publisher(s) Cage, and featuring Marcel Duchamp with whom he played chess on a Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal photo-sensitive electronic chessboard. ISSN 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rea, J. (2009). On Stockhausen’s Kontakte (1959-60) for tape, piano and percussion: A lecture/analysis by John Rea given at the University of Toronto, march 1968. Circuit, 19(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.7202/037453ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Robert Starer: a Remembrance 3

21ST CENTURY MUSIC AUGUST 2001 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 (print) and $42.00 (e-mail) per year; subscribers to the print version elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $8.00 (print) and $4.00 (e-mail) Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. e-mail: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2001 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy.