When Timbers Tremored in the Cary Mine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aftermath : Seven Secrets of Wealth Preservation in the Coming Chaos / James Rickards

ALSO BY JAMES RICKARDS Currency Wars The Death of Money The New Case for Gold The Road to Ruin Portfolio/Penguin An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2019 by James Rickards Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rickards, James, author. Title: Aftermath : seven secrets of wealth preservation in the coming chaos / James Rickards. Description: New York : Portfolio/Penguin, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019010409 (print) | LCCN 2019012464 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216952 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Investments. | Financial crises. | Finance—Forecasting. | Economic forecasting. Classification: LCC HG4521 (ebook) | LCC HG4521 .R5154 2019 (print) | DDC 332.024—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010409 Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Europe the Way IT Once Was (And Still Is in Slovenia) a Tour Through Jerry Dunn’S New Favorite European Country Y (Story Begins on Page 37)

The BEST things in life are FREE Mineards’ Miscellany 27 Sep – 4 Oct 2012 Vol 18 Issue 39 Forbes’ list of 400 richest people in America replete with bevy of Montecito B’s; Salman Rushdie drops by the Lieffs, p. 6 The Voice of the Village S SINCE 1995 S THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 44 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 48 EuropE ThE Way IT oncE Was (and sTIll Is In slovEnIa) A tour through Jerry Dunn’s new favorite European country y (story begins on page 37) Let the Election Begin Village Beat No Business Like Show Business Endorsements pile up as November 6 nears; Montecito Fire Protection District candidate Jessica Hambright launches Santa Barbara our first: Abel Maldonado, p. 5 forum draws big crowd, p. 12 School for Performing Arts, p. 23 A MODERNIST COUNTRY RETREAT Ofered at $5,995,000 An architecturally significant Modernist-style country retreat on approximately 6.34 acres with ocean and mountain views, impeccably restored or rebuilt. The home features a beautiful living room, dining area, office, gourmet kitchen, a stunning master wing plus 3 family bedrooms and a 5th possible bedroom/gym/office in main house, and a 2-bedroom guest house, sprawling gardens, orchards, olives and Oaks. 22 Ocean Views Private Estate with Pool, Clay Court, Guest House, and Montecito Valley Views Offered at $6,950,000 DRE#00878065 BEACHFRONT ESTATES | OCEAN AND MOUNTAIN VIEW RETREATS | GARDEN COTTAGES ARCHITECT DESIGNED MASTERPIECES | DRAMATIC EUROPEAN STYLE VILLAS For additional information on these listings, and to search all currently available properties, please visit SUSAN BURNS www.susanburns.com 805.886.8822 Grand Italianate View Estate Offered at $19,500,000 Architect Designed for Views Offered at $10,500,000 33 1928 Santa Barbara Landmark French Villa Unbelievable city, yacht harbor & channel island views rom this updated 9,000+ sq. -

Cedars, November 2012 Cedarville University

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 11-2012 Cedars, November 2012 Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville University, "Cedars, November 2012" (2012). Cedars. 25. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/25 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Student News Publication of Cedarville University November 2012 Dr. Brown: Not a Quick Decision ‘I’m just glad it’s a long goodbye.’ T ble of Contents November 2012 Vol. 65, No. 4 Just Sayin’ ... Page 3 Hypocritical Hallelujahs November Calendar e’ve all heard the ing myself that I’m following Christ when my Pages 4-8 countless stories actions don’t match up, or convincing myself Cover Story: Dr. Brown Resigns about hypocriti- that I would never be one of those hypocritical Page 9 W cal Christians, those who Christians frequently talked about in the media American Dream Conference claim to love Christ but or in conversations. -

The Price of Gold

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 15, July 1952 THE PRICE OF GOLD MIROSLAV A. KRIZ INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION 1.DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New1 Jersey This is the fifteenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTER- NATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics and Social Institutions in Princeton University. It is the second in the series written by the present author, the first one, "Postwar International Lending," having been published in the spring of 1947 and long since out of print. The author, Miroslav A. Kriz, is on the staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. From 1936 to 1945 he was a member of the Economic and Fi- nancial Department of the League of Nations. While the Section sponsors the essays in this series, it takes no further responsibility for the opinions therein expressed. The writers are free to develop their topics as they, will and their ideas may or may not be shared by the .editorial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. Nor do the views _the writer expresses purport to reflect those of the institution with which he is associated. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section THE PRICE OF GOLD MIROSLAV A: KRIZ Federal Reserve Bank of New Y orki I. INTRODUCTION . OLD in the world today has many facets. -

Buffalo's Gold Rush

Speech To Saturn Club Buffalo, New York By Robert J.A. Irwin February 16, 2005 Buffalo’s Gold Rush (Informal remarks about candy gold coins passed out at dinner.) Gold is ideal for coins. It is extremely malleable, it’s beautiful and it doesn’t tarnish. Some of the most beautiful gold coins in the world have been minted by the United States since shortly after our Revolutionary War until 1933 and then from 1986 until now. Their appearance has been controversial, particularly with regard to the motto, “In God We Trust” inscribed by law on all our coins since 1866. In. 1866 the then Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon Chase declared, “No nation can be strong except in the strength of God, or safe except in his defense. The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins.” When Theodore Roosevelt became President in the early 20th Century he decided it was time to design a more exciting and modern looking $20 gold piece to replace the rather prosaic Liberty Head design. He commissioned his friend and noted sculptor, August St-Gaudens to create a new design and omit “In God We Trust.” Roosevelt was a religious man but he believed that it was inappropriate for 1 a coin that would be thrown around in bars and gambling hells to carry an invocation to our deity. St-Gaudens’ beautiful new coin with a standing figure of Liberty and no motto was issued in 1907. The next year responding to national outrage Congress ordered that the motto be reinstated. -

Where Keynes Went Wrong

Praise for Where Keynes Went Wrong “[An] impassioned . and . much needed book. In plain prose, . Hunter Lewis . begins by patiently walking us through precisely what Keynes said . then reveals why Keynes’s work is ‘remarkably unsupported by evidence or logic.’ Lewis does much more besides, showing how Keynesianism has lived in the minds and hearts of politicians, with disastrous results.” —Gene Epstein, Barron’s “Lewis has exposed with unmatched clarity the lineaments of Keynes’s system and enabled us to see exactly its disabling defects. Keynes defied common sense, unable to sustain the brilliant para- doxes that his fertile intellect constantly devised. Lewis’s book is an ideal guide to Keynes’s dangerous and destructive economics. .” —David Gordon, LewRockwell.com “Just what the world needs, and just in time. Keynes is demolished and his quack system refuted. But this wonderful book does more. It restores clear thinking and common sense to their rightful places in the economic policy debate. Three cheers for Hunter Lewis!” —James Grant, Editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer “Hunter Lewis has written a splendid book called Where Keynes We nt Wrong. The dissection of the English economist who died in 1946 is especially timely, given that the past two administra- tions and the current one are identical in believing wholeheart- edly in . key Keynesian dogma.” —Patrick McIlheran, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel “[This] compelling, powerful, and extremely readable book . is fantastic. ‘Must’ reading.” —Kevin Price, CBS and CNN Radio and BizPlusBlog “Lewis has done a service, even if in the negative, of concisely and critically summarizing Keynes’s economic theories, and his book will make readers think.” —Library Journal “[This] highly readable . -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

Vol. 30, No. 6 June 1968 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTIIIES • The Ore Bin • Published Monthly 8y STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland, Oregon - 97201 Telephone: 226 ... 2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 521 N. E. liE" Street Bak.. 97814 Grants Pas. 97526 Subscription rote $1 . 00 per year. Available back Issues 10 cents each. • • * • * • * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * • • * * * Second class postage paid at Portland, Oregon • * * * • • * • * • * * • * • • * * • • • * * * * * • • • * * • * • * • * * • GOVERNING BOARD Fronk C . McColloch, Chalrmon, Portland Fayette I. tristol, Gronts Poss Harold Bonta, 8ak..- STATE GEOLOGIST Hollis M. Dole GEOLOGISTS IN CHARGE OF FIELD OFFICES Norman S. Wagner. Boker Len Ramp, Grants PaIS P. mi$$ion is granted to reprint infonl'lCl lion c:onfolned h ..ei n. Any credit given the State of Oregon Deportmen t of Geology ond Mi ner(ll Inmnlries for compiling this information wi ll be opprec:loted . State of Oregon The ORE BI N Department of Geology Volume 30, No.6 and Mineral Indcstries 1069 State Offi ce BI dg. June 1968 Portland Oregon 97201 THE GOLDEN YEARS OF EASTERN OREGON By Mi les F. Potter and Harold McCall The following pictorial article on the golden years of eastern Oregon, by Mi les F. Potter and Harold McCall, is an abstract from their man uscript of a forthcoming book they are calling "Golden Pebbles." Potter is a long-time resident of eastern Oregon and an amateur his torian of some of the early gold camps in Grant and Baker Counties. McCall is a photographer in Oregon City with a keen interest in the history of gold mining. -

CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING California Gold Rush

CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING California Gold Rush OCTOBER 1999 CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH PREOPENING DEN PACK ACTIVITIES PACK GOLD RUSH DAY Have each den adopt a mining town name. Many towns and mining camps in California’s Gold Country had colorful names. There were places called Sorefinger, Flea Valley, Poverty Flat (which was near Rich Gulch), Skunk Gulch, and Rattlesnake Diggings. Boys in each den can come up with an outrageous name for their den! They can make up a story behind the name. Have a competition between mining camps. Give gold nuggets (gold-painted rocks) as prizes. Carry prize in a nugget pouch (see Crafts section). For possible games, please see the Games section. Sing some Gold Rush songs (see Songs section). As a treat serve Cheese Puff “gold nuggets” or try some of the recipes in the Cubs in the Kitchen section. For more suggestions see “Gold Rush” in the Cub Scout Leader How-to Book , pp. 9- 21 to 9-23. FIELD TRIPS--Please see the Theme Related section in July. GOLD RUSH AND HALLOWEEN How about combining these two as a part of a den meeting? Spin a tale about a haunted mine or a ghost town. CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH James Marshall worked for John Augustus Sutter on building a sawmill on the South Fork of the American River near the area which is now the town of Coloma. On January 24, 1848, he was inspecting a millrace or canal for the sawmill. There he spotted a glittering yellow pebble, no bigger than his thumbnail. Gold, thought Marshall, or maybe iron pyrite, which looks like gold but is more brittle. -

The Intrinsic Value of Gold: an Exchange Rate-Free Price Index Richard D. F. Harris University of Exeter Jian Shen University Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Exeter The Intrinsic Value of Gold: An Exchange Rate-Free Price Index Richard D. F. Harris University of Exeter Jian Shen University of Exeter July 2017 Abstract In this paper, we propose a gold price index that enables market participants to separate the change in the ‘intrinsic’ value of gold from changes in global exchange rates. The index is a geometrically weighted average of the price of gold denominated in different currencies, with weights that are proportional to the market power of each country in the global gold market. Market power is defined as the impact that a change in a country’s exchange rate has on the price of gold expressed in other currencies. We use principal components analysis to reduce the set of global exchange rates to four currency ‘blocs’ representing the U.S. dollar, the euro, the commodity currencies and the Asian currencies, respectively. We estimate the weight of each currency bloc in the index in an error correction framework using a broad set of variables to control for the unobserved intrinsic value. We show that the resulting index is less volatile than the USD price of gold and, in contrast with the USD price of gold, has a strong negative relationship with global equities and a strong positive relationship with the VIX index, both of which underline the role of gold as a safe haven asset. Keywords: Gold price index; Commodities; Exchange rates; Cointegration; Error correction mechanism. -

Gold Among the ’Heels

ECONOMICHISTORY Gold Among the ’Heels BY BETTY JOYCE NASH News of gold hen people say the streets comparison to California’s, which of Charlotte are paved produced gold estimated at $200 discoveries pulled in Wwith gold, they’re not million (in that era’s dollars). North speaking metaphorically. They may Carolina’s output totaled about $17.5 experts, captains of very well be flecked with gold under- million between 1799 and 1860, neath the asphalt. excluding gold that was bartered or industry, money, and Eleven years after the Constitution shipped abroad. (The price of gold was ratified and 50 years before hovered around $20 per ounce miners to the sleepy the Forty-niners rushed to California, throughout the 19th century.) a Cabarrus County, N.C., farm boy In contrast to the wild California backwater that was picked from a creek a shiny rock that migration from around the globe to his father used as a doorstop for stake claims, the North Carolina rush early 19th century three years. At least, that’s the story. seems subdued. But from 1804 until It brought $3.50 from a Fayetteville 1828, all domestic gold coined at the North Carolina. jeweler but was worth $3,600. The U.S. Mint in Philadelphia came from rock turned out to be a 17-pound the Tarheel state. At the time, gold nugget, and there was more however, precious little came back where that came from — the Reed home to circulate. Gold Mine. News of North Carolina gold set Grains of Gold off a half century of discoveries in the New World explorers searched for South, from Virginia to Alabama. -

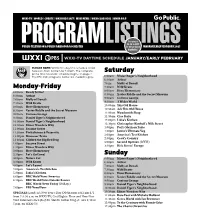

Program Listings

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 See pages 25-30 in CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSfor our program JANUARY/EARLY FEBRUARY 2021 highlights! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE JANUARY/EARLY FEBRUARY PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete Saturday prime time television schedule begins on page 2. The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 8:00am 6:00am Ready Jet Go! Hero Elementary 8:30am 6:30am Arthur Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 9:00am 7:00am Molly of Denali Curious George 9:30am 7:30am Wild Kratts A Wider World 10:00am 8:00am Hero Elementary This Old House 10:30am 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum Ask This Old House 11:00am 9:00am Curious George Woodsmith Shop 11:30am 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Ciao Italia 12:00pm 10:00am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Lidia’s Kitchen 12:30pm 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street 1:00pm 11:00am Sesame Street Pati’s Mexican Table 1:30pm 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific Jamie’s Ulitmate Veg 2:00pm 12:00pm Dinosaur Train America’s Test Kitchen 2:30pm 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog Cook’s Country 3:00pm (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street Second Opinion 3:30pm 1:30pm Elinor Wonders Why Rick Steves’ Europe 2:00pm Hero Elementary 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! Sunday 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:30pm Wild Kratts 6:30am Arthur 4:00pm Let’s Learn! 7:00am Molly of Denali 5:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 7:30am Wild Kratts 5:30pm Lidia’s Kitchen 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:00pm BBC Wold News America 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 6:30pm BBC World News Outside Source 9:00am Curious George BBC World News Today (Fridays) 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 7:00pm PBS NewsHour 10:00am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood SPECIALS: London’s New Year’s Day Celebration 2021 airs 1/1 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why from 7-9:30 a.m.