Land, Labor and Production: the Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release from Otis College for the California Edition

Please contact Communications for media inquiries 310-665-6857 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Creative Workforce Contributes $217 Billion and Rising to California’s Gross Product; Success Linked to Job Opportunity Finds Otis Report on the Creative Economy Hearing to review the findings of the 2015 Otis Report on the Creative Economy of California held by the Legislative Joint Committee on the Arts in Sacramento; Report includes new regional snapshots highlighting local creative industries SACRAMENTO, CA – May 11th, 2016 - The results of the 2015 Otis Report on the Creative Economy of California (Otis Report) were unveiled today in a state Capitol hearing before the Legislative Joint Committee on the Arts in Sacramento, chaired by Senator Ben Allen. The Otis Report has become a powerful advocacy tool and catalyst for change by clearly articulating the economic benefits of the creative industries and quantifying their financial impact in the economy. Otis College of Art and Design has commissioned the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (LAEDC) to generate the Annual Report on the Creative Economy of the Los Angeles Region (Otis Report) since 2007. Now in its third year, the Otis Report on the Creative Economy of California features an expansion highlighting local creative industries via eight regional snapshots, developed with support from the California Arts Council. The regions include: Bay Area, Capital Region, Central Coast, Inland Empire, Central Valley, San Diego- Imperial Valley, Los Angeles-Orange County, and Upstate California. “The statewide Otis Report has been a game-changer for California’s arts field over the past three years,” said Craig Watson, Director of the California Arts Council. -

Los Angeles Region 2017 2017

blue cool Light Pantone pantone 3115 grey 10 cool Blue 3955 grey 072 pantone 381 4 0 100 0 LOS ANGELES REGION 2017 2017 Prepared for Otis College of Art and Design by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation. 2017 SECONDARY TREATMENT FOR DATE WHEN USED FOR EBLASTS THANK YOU REPORT SPONSORS ALAN ZAFRAN MEDIA PARTNERS blue cool Light Pantone pantone 3115 grey 10 cool Blue 3955 grey 072 pantone 381 4 0 100 0 2017 2017 2017 SECONDARY TREATMENT FOR DATE WHEN USED FOR EBLASTS 2017 OTIS REPORT on the Creative Economy of the LOS ANGELES REGION May 2017 Prepared for Otis College of Art and Design by the INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED ECONOMICS Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation PREPARED AND RESEARCHED BY: PROJECT MANAGED BY: Somjita Mitra, Ph.D. Christine Leahey Senior Economist Director of Stategic Partnerships Kimberly Ritter-Martinez Claudia Beinkinstadt Krumlauf Economist Development & Special Events Manager Rafael DeAnda Chelsey Sobel Associate Economist Coordinator, Institutional Advancement ABOUT THE KYSER CENTER FOR ECONOMIC Anne Swett-Predock RESEARCH Creative Direction The LAEDC Institute for Applied Economics spe- Sean Yoon cializes in objective and unbiased economic and Design and Production public policy research in order to foster informed decision-making and guide strategic planning. In ABOUT OTIS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN addition to commissioned research and analysis, the Institute conducts foundational research to Established in 1918, Otis College of Art and Design ensure LAEDC’s many programs for economic offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in development are on target. The Institute focuses a wide variety of visual and applied arts, media, on economic impact studies, regional industry and and design. -

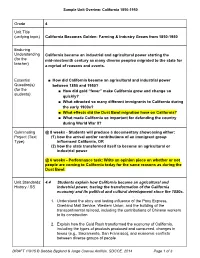

Grade 4 Unit Title (Unifying Topic) California Becomes Golden

Sample Unit Overiew: California 18501950 Grade 4 Unit Title (unifying topic) California Becomes Golden: Farming & Industry Grows from 18501950 Enduring Understanding California became an industrial and agricultural power starting the (for the midnineteenth century as many diverse peoples migrated to the state for teacher) a myriad of reasons and events. Essential ■ How did California become an agricultural and industrial power Question(s) between 1850 and 1950? (for the ■ How did gold “fever” make California grow and change so students) quickly? ■ What attracted so many different immigrants to California during the early 1900s? ■ What effects did the Dust Bowl migration have on California? ■ What made California so important for defending the country during World War II? Culminating @ 8 weeks Students will produce a documentary showcasing either: Project (Text (1) how the arrival and/or contributions of an immigrant group Type) influenced California, OR (2) how the state transformed itself to become an agricultural or industrial power @ 6 weeks Performance task: Write an opinion piece on whether or not people are coming to California today for the same reasons as during the Dust Bowl. Unit Standards: 4.4 Students explain how California became an agricultural and History / SS industrial power, tracing the transformation of the California economy and its political and cultural development since the 1850s. 1. Understand the story and lasting influence of the Pony Express, Overland Mail Service, Western Union, and the building of the transcontinental railroad, including the contributions of Chinese workers to its construction. 2. Explain how the Gold Rush transformed the economy of California, including the types of products produced and consumed, changes in towns (e.g., Sacramento, San Francisco), and economic conflicts between diverse groups of people. -

The Economic Aspects of California Missions, Robert Archibald

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Franciscan Publications Spanish Viceroyalty [AD 1542/1769-1821] 2-1-2017 1978 – The Economic Aspects of California Missions, Robert Archibald Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_spa_2 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "1978 – The Economic Aspects of California Missions, Robert Archibald" (2017). Franciscan Publications. 1. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_spa_2/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish Viceroyalty [AD 1542/1769-1821] at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Franciscan Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE CALIFORNIA MISSIONS ROBERT ARCHIBALD ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTORY WASHINGTON, D.C. t CUM PERM!SSU SUPERIORUM COPYRIGHT, 1978, BY ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTORY PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE WILLIAM BYRD PRESS, INC RICHMOND, VIRGINIA THE ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE CALIFORNIA MISSIONS Table of Contents Page Introduction XI Chapter I. Economic Features of Institutes of Government . 1 II. Price Regulation . 11 III. The Connection with San Blas . 2 7 IV. Mission Reports and Accounts . 6 3 V. Mission Economic Relationships with Civilians, Military and Government 74 VI. Trade with the Outside World . 115 VII. Mission Labor . 142 VIII. Mission Agriculture . 159 Conclusion . 18 3 Bibliography . 18 7 Index . 191 List of Tables Tu� �e 1. Selected Shipments from San Blas . .. .. .. .. 12 2. Prices for Goods Received at Mission San Carlos . -

Impact of Calstrs' Investments on California's Economy

TEACHERS’ RETIREMENT BOARD REGULAR MEETING Item Number: 9 SUBJECT: Economic Impact of CalSTRS Investments CONSENT: ATTACHMENT(S): 1 ACTION: DATE OF MEETING: November 6, 2014 / 45 mins. INFORMATION: X PRESENTER: Ed Derman ______________________________________________________________________________ PURPOSE The purpose of this item is to introduce the 2014 study of the economic impact of CalSTRS investments in California. BACKGROUND At the September 2013 meeting, the results of a study of the economic impact of benefits paid by CalSTRS were presented to the board. The study being presented at this meeting uses a sectoral- share approach to estimate jobs supported in California by the companies in the CalSTRS investment portfolio. Data from the four main asset classes were evaluated. These asset classes account for about 96 percent of the total portfolio and include: global equities (57 percent of the portfolio), fixed income (16 percent), real estate (12 percent) and private equity (11 percent). There is no universally accepted methodology for a study of this type because the impact of financial markets on the “real economy” (employment, real wages, interest rates and so on) is often debated by economists. While the impact of an investment in a start-up company can be quantified more directly, the impact of secondary investments in non-IPO shares of stocks or bonds is more diffused and complex. Nonetheless, CalSTRS’ investments in these markets provide critical financing for ongoing operations of these companies. KEY FINDINGS This item highlights the key finding of the study as the full report from Dr. Ashok Bardhan is attached. For calendar year 2013, CalSTRS’ investments in California in public equities, fixed income, private equity and real estate totaled $19.38 billion—15.2 percent—of CalSTRS’ $127.4 billion invested in the U.S. -

Immigration and the Political Economy of Public Education: Recent Perspectives

IZA DP No. 8778 Immigration and the Political Economy of Public Education: Recent Perspectives Francesc Ortega Ryuichi Tanaka January 2015 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Immigration and the Political Economy of Public Education: Recent Perspectives Francesc Ortega Queens College, CUNY and IZA Ryuichi Tanaka National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies Discussion Paper No. 8778 January 2015 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

California History Online | the Physical Setting

Chapter 1: The Physical Setting Regions and Landforms: Let's take a trip The land surface of California covers almost 100 million acres. It's the third largest of the states; only Alaska and Texas are larger. Within this vast area are a greater range of landforms, a greater variety of habitats, and more species of plants and animals than in any area of comparable size in all of North America. California Coast The coastline of California stretches for 1,264 miles from the Oregon border in the north to Mexico in the south. Some of the most breathtaking scenery in all of California lies along the Pacific coast. More than half of California's people reside in the coastal region. Most live in major cities that grew up around harbors at San Francisco Bay, San Diego Bay and the Los Angeles Basin. San Francisco Bay San Francisco Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in the world, covers some 450 square miles. It is two hundred feet deep at some points, but about two-thirds is less than twelve feet deep. The bay region, the only real break in the coastal mountains, is the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok Indians. It became the gateway for newcomers heading to the state's interior in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tourism today is San Francisco's leading industry. San Diego Bay A variety of Yuman-speaking people have lived for thousands of years around the shores of San Diego Bay. European settlement began in 1769 with the arrival of the first Spanish missionaries. -

California 2017 2017

blue cool Light Pantone pantone 3115 grey 10 cool Blue 3955 grey 072 pantone 381 4 0 100 0 CALIFORNIA 2017 2017 Prepared for Otis College of Art and Design by the INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED ECONOMICS Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation 2017 SECONDARY TREATMENT FOR DATE WHEN USED FOR EBLASTS THANK YOU REPORT SPONSORS ALAN ZAFRAN MEDIA PARTNERS blue cool Light Pantone pantone 3115 grey 10 cool Blue 3955 grey 072 pantone 381 4 0 100 0 2017 2017 2017 SECONDARY TREATMENT FOR DATE WHEN USED FOR EBLASTS 2017 OTIS REPORT on the Creative Economy of CALIFORNIA May 2017 Prepared for Otis College of Art and Design by the INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED ECONOMICS Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation PREPARED AND RESEARCHED BY: PROJECT MANAGED BY: Somjita Mitra, Ph.D. Christine Leahey Senior Economist Director of Stategic Partnerships Kimberly Ritter-Martinez Claudia Beinkinstadt Krumlauf Economist Development & Special Events Manager Rafael DeAnda Chelsey Sobel Associate Economist Coordinator, Institutional Advancement ABOUT THE KYSER CENTER FOR ECONOMIC Anne Swett-Predock RESEARCH Creative Direction The LAEDC Institute for Applied Economics Sean Yoon specializes in objective and unbiased economic Design and Production and public policy research in order to foster informed decision-making and guide strategic ABOUT OTIS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN planning. In addition to commissioned research and analysis, the Institute conducts foundational Established in 1918, Otis College of Art and research to ensure LAEDC’s many programs Design offers undergraduate and graduate for economic development are on target. The degrees in a wide variety of visual and applied Institute focuses on economic impact studies, arts, media, and design. -

Atlas of Social and Economic Conditions and Change in Southern California

United States Department of Agriculture Atlas of Social and Economic Forest Service Pacific Northwest Conditions and Change in Research Station General Technical Southern California Report PNW-GTR-516 September 2001 Terry L. Raettig, Dawn M. Elmer, and Harriet H. Christensen SSOUTHERNOUTHERN CALIFORNIACALIFORNIA Authors Terry L. Raettig was an economist (retired), Pacific Northwest Research Station, stationed at Olympic National Forest, 1835 Black Lake Blvd. S.W., Olympia, WA 98512-5623; Dawn M. Elmer was a social science associate, and Harriet H. Christensen is a supervisory research social scientist, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 4043 Roosevelt Way N.E., Seattle, WA 98105-6497. Atlas of Social and Economic Conditions and Change in Southern California Terry L. Raettig Dawn M. Elmer Harriet H. Christensen U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-516 September 2001 Abstract Raettig, Terry L.; Elmer, Dawn M.; Christensen, Harriet H. 2001. Atlas of social and economic conditions and change in southern California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-516. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 66 p. This atlas illustrates the spatial and temporal dimensions of social and economic changes in the social-econ o m i c assessment region in the decade since 1987/1988. Maps, interpretive text, and accompanying tables and graphs portray conditions, trends, and changes in selected social, economic, and natural resource-related indicators for the 26 counties of the diverse region during a period of particularly rapid and intense demo- graphic, social, and economic change. This information about the people, communities, and resources of the region serves as a tool for natural resource planners and managers, economic development practitioners, and citizens interested and involved in the future of the region. -

Amendment to the Notice of Treatment for the Asian Citrus Psyllid

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE OFFICIAL NOTICE FOR THE CITIES OF KERN COUNTY PLEASE READ IMMEDIATELY AMENDMENT TO THE NOTICE OF TREATMENT FOR THE ASIAN CITRUS PSYLLID Between September 16, 2020 to February 17, 2021 the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) confirmed the presence of Asian citrus psyllid (ACP), Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, a harmful exotic pest in the cities of Arvin, Bakersfield, Edmundson Acres, Fuller Acres, Lamont, Maricopa, Mettler, Oildale, Rosedale, and Weedpatch in Kern County. This detection indicate that a breeding population exists in the area. The devastating citrus disease Huanglongbing (HLB) is spread by the feeding action of ACP. The ACP infestation is sufficiently isolated and localized to be amenable to the CDFA’s ACP treatment work plan. A Program Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) has been certified which analyzes the ACP treatment program in accordance with Public Resources Code, Sections 21000 et seq. The PEIR is available at http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/peir/. The treatment activities described below are consistent with the PEIR. In accordance with integrated pest management principles, CDFA has evaluated possible treatment methods and determined that there are no physical, cultural, or biological control methods available to eliminate the ACP from this area. Notice of Treatment is valid until February 17, 2022, which is the amount of time necessary to determine that the treatment was successful. The treatment plan for the ACP infestation will be implemented within a 50 to 400-meter radius of the ACP detection(s), as follows: • Tempo® SC Ultra (cyfluthrin), a contact insecticide for controlling the adults and nymphs of ACP, will be applied from the ground using hydraulic spray equipment to the foliage of host plants; and • Merit® 2F or CoreTect™ (imidacloprid), a systemic insecticide for controlling the immature life stages of ACP, will be applied to the soil underneath host plants. -

History Standards

Lake Tahoe Unified School District STANDARDSforHISTORY/SOCIAL SCIENCE I the location of Mexican the growth of towns and cities (e.g., settlements in California and other Los Angeles) settlements including Ft. Ross and I the effects of the Great Fourth Grade Sutter's Fort Depression, the Dust Bowl and I Students learn the story of their home state, unique in American history in comparisons of how and why World War II on California people traveled to California and terms of its vast and varied geography, its many waves of immigration I the development and location of beginning with pre-Columbian societies, its continuous diversity, economic the routes they traveled (e.g., biographies and legends of James new industries since the turn of the energy, and rapid growth. In addition to the specific treatment of century, such as aerospace, milestones in California history, students examine the state in the context Beckwourth, Jedediah Smith, John C. Fremont, Juan Cabrillo) electronics, large scale commercial of the rest of the nation, with an emphasis on the U.S. Constitution and the I the effect of the Gold Rush on agriculture and irrigation projects, relationship between state and federal government. settlements, daily life, politics and the oil and automobile industries, the physical environment (e.g., communications and defense, and biographies of John Sutter, Mariano important trade links with the distribution, economic activities, Guadalupe Vallejo, Phoebe legends and religious beliefs; and Pacific Basin Apperson Hearst) I California's water system and how they depended upon, adapted I the immigration and migration to to and modified the physical how it evolved over time into a environment by cultivation of network of dams, aqueducts and land and sea resources reservoirs I the early land and sea routes I the history and development of to, and European settlements in, California's public education California with a focus on the system, including universities and 1. -

When Home Bibliography-Scholarly Publications-California-Focused

Scholarly Publications About Migration Spotlight on California • Robert E. Barde, Immigration at the Golden Gate: Passenger Ships, Exclusion, and Angel Island (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2008). From the publisher: Presents the history of San Francisco's Angel Island Immigration Station that operated between 1910 and 1940. Argues that Asian immigrants, rather than being welcomed, were denied liberties and even entrance to the United States. • Albert S. Broussard, Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900–1954 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1993). From the publisher: When it came to racial equality in the early twentieth century, Albert S. Broussard argues, the liberal, progressive image of San Francisco was largely a facade. In this book, he challenges the rhetoric of progress and opportunity with evidence of the reality of inequality and shows how black San Franciscans struggled for equality in the same manner as their counterparts in the Midwest and East. Understanding the texture of the racial caste system in the city prior to 1954, he contends, is critical to understanding why blacks made so little progress in employment, housing, and politics despite the absence of segregation laws. Reconstructing the plight of San Francisco's black citizens, Broussard reveals a population that, despite its small size before 1940, did not accept second-class citizenship passively yet remained nonviolent into the 1960s. He also shows how World War II and the defense industry brought thousands of southern black migrants to the bay area. Ultimately, he demonstrates, these newcomers and native black residents formed coalitions with white liberals to attack racial inequality more vigorously and successfully than at any previous time in San Francisco's history.