Deep Geothermal Energy K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microgeneration Potential in New Zealand

Prepared for Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Microgeneration Potential in New Zealand A Study of Small-scale Energy Generation Potential by East Harbour Management Services ISBN: 1-877274-33-X May 2006 Microgeneration Potential in New Zealand East Harbour Executive summary The study of the New Zealand’s potential for micro electricity generation technologies (defined as local generation for local use) in the period up to 2035 shows that a total of approximately 580GWh per annum is possible within current Government policies. If electricity demand modifiers (solar water heating, passive solar design, and energy efficiency) are included, there is approximately an additional 15,800GWh per annum available. In total, around 16,400GWh of electricity can be either generated on-site, or avoided by adopting microgeneration of energy services. The study has considered every technology that the authors are aware of. However, sifting the technologies reduced the list to those most likely to be adopted to a measurable scale during the period of the study. The definition of micro electricity generation technologies includes • those that generate electricity to meet local on-site energy services, and • those that convert energy resources directly into local energy services, such as the supply of hot water or space heating, without the intermediate need for electricity. The study has considered the potential uptake of each technology within each of the periods to 2010, 2020, and 2035. It also covers residential energy services and those services for small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that can be obtained by on-site generation of electricity or substitution of electricity. -

Geothermal Energy

Geothermal energy Adele Manzella CNR - Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources Via Moruzzi 1 – 56124 PISA, Italy [email protected] Geothermal Energy Pros Cons Research What is How is used frontiers Status and perspectives What is the source of geothermal energy? What part is used? What is Geothermal Energy IGG – Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources National Research Council of Italy WHAT is Geothermal energy Geothermal Energy The basis of geothermal energy is the From Greek gêo (earth) e immense heat content of the earth’s thermòs (heat) interior: the Earth is slowly cooling down. Since billions of years the heat in the Earth Crust is constantly supplied by Heat inside the Earth the decay of natural radioactive isotopes or the cooling of hot, shallow magmatic ~ 30 °C/km bodies. > 1000 °C > 3000 °C The resource is vast and ubiquitous and > 5000 °C has a corresponding large potential for utilization. WHAT is Geothermal energy Temperature in the ground has a daily (few cm) and seasonal (few meters) fluctuations, becoming essentially constant and equal to the average air temperature at about 18-20 m depth. Below this depth, it essentially increases with depth (geothermal gradient). Shallow geothermal: exploits the underground constant T= average air T The resource is vast and ubiquitous and has a corresponding large potential for Deep geothermal: exploits the utilization. underground heat at T>> air T WHAT is Geothermal energy The temperature increase with depth, as well as volcanoes, geysers, hot springs etc., are in a sense the visible or tangible expression of the heat in the interior of the Earth, but this heat also engenders other phenomena that are less discernable by man, but of such magnitude that the Earth has been compared to an immense "thermal engine”. -

Geothermal Gradient Calculation Method: a Case Study of Hoffell Low- Temperature Field, Se-Iceland

International Research Journal of Geology and Mining (IRJGM) (2276-6618) Vol. 4(6) pp. 163-175, September, 2014 DOI: http:/dx.doi.org/10.14303/irjgm.2014.026 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/irjgm Copyright©2014 International Research Journals Full Length Research Paper Geothermal Gradient Calculation Method: A Case Study of Hoffell Low- Temperature Field, Se-Iceland Mohammed Masum Geological Survey of Bangladesh, 153, Pioneer Road, Segunbagicha, Dhaka-1000, BANGLADESH E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The study area is a part of the Geitafell central volcano in southeast Iceland. This area has been studied extensively for the exploration of geothermal resources, in particular low-temperature, as well as for research purposes. During the geothermal exploration, geological maps should emphasize on young corresponding rocks that could be act as heat sources at depth. The distribution and nature of fractures, faults as well as the distribution and nature of hydrothermal alteration also have to known. This report describes the results of a gradient calculation method which applied to low-temperature geothermal field in SE Iceland. The aim of the study was to familiarize the author with geothermal gradient mapping, low-temperature geothermal manifestations, as well as studying the site selection for production/exploration well drilling. Another goal of this study was to make geothermal maps of a volcanic field and to analyse if some relationship could be established between the tectonic settings and the geothermal alteration of the study area. The geothermal model of the drilled area is consistent with the existence of a structurally controlled low-temperature geothermal reservoir at various depths ranging from 50 to 600 m. -

Geothermal Energy

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 519 Geothermal Energy Geothermal Energy By Donald E. White GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 519 Washington 1965 United States Department of the Interior STEWART l. UDALL, Secretary Geological Survey William T. Pecora, Director First printing 1965 Second printing 1966 Free on application to the U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. 20242 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract--------------------------- 1 Hydrothermal systems of composite Introduction------------------------ 1 type---------------------------- 9 Acknowledgments------------------- 2 General problems of utilization ----- 10 Areas of "normal" geothermal Domestic and world resources of gradient ------------------------- 2 geothermal energy--------------- 12 Large areas of higher-than-"normal" Assumptions# statistics, and geothermal gradient--------------- 3 conversion factors--------------- 14 Hot spring areas-------------------- 4 References cited___________________ 14 TABLE Page Table 1. Natural heat flows of some hot spring areas of the world--------------------- 5 III Geothermal Energy By Donald E. White ABSTRACT commercially developed hot spring areas at rates of five to more than 10 times their rates of natural heat flow prior to The earth is a tremendous reservoir of heat, most of which development. Such overdrafts, in at least some systems, can is too deeply buried or too diffuse to consider as recoverable continue for many years, the excess heat being suppli-ed energy. Some large areas are higher-than-"normal" in heat from the heat reservoir. Eventually, depending on the char content, particularly in regions of volcanic and tectonic ac acteristics of each individual system, the effects of sus tivity. Recovery of stored heat from these large areas may tained overdraft must become evident. be economically feasible in the future but cannot compete in cost now with other forms of energy. -

Deep Geothermal Processes Acting on Faults and Solid Tides in Coastal

Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 264 (2017) 76–88 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pepi Deep geothermal processes acting on faults and solid tides in coastal Xinzhou geothermal field, Guangdong, China ⇑ Guoping Lu a,b, , Xiao Wang b, Fusi Li b, Fangyiming Xu b, Yanxin Wang b, Shihua Qi b, David Yuen c a State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China b School of Environmental Studies, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China c Institute of Supercomputing, The University of Minnesota, Twins, United States article info abstract Article history: This paper investigated the deep fault thermal flow processes in the Xinzhou geothermal field in the Received 13 April 2016 Yangjiang region of Guangdong Province. Deep faults channel geothermal energy to the shallow ground, Received in revised form 27 December 2016 which makes it difficult to study due to the hidden nature. We conducted numerical experiments in order Accepted 27 December 2016 to investigate the physical states of the geothermal water inside the fault zone. We view the deep fault as Available online 29 December 2016 a fast flow path for the thermal water from the deep crust driven up by the buoyancy. Temperature mea- surements at the springs or wells constrain the upper boundary, and the temperature inferred from the Keywords: Currie temperature interface bounds the bottom. The deepened boundary allows the thermal reservoir to Solid tide revolve rather than to be at a fixed temperature. The results detail the concept of a thermal reservoir in Geothermal Reservoir terms of its formation and heat distribution. -

Geothermal Energy Thermal Energy Is Constantly Gene- Rated in the Earth Interior by the De- Cay of Radioactive Nuclei

Geothermal energy Thermal energy is constantly gene- rated in the Earth interior by the de- cay of radioactive nuclei. The heat content of the Earth is 1031 Joules. This heat naturally flows up to the surface by conduction at a rate of 45 TW, or three times the rate of human consump- tion from all prima- ry energy sources. However, the bulk of this natural flow is too geographically Current global usage of energy is about 5×1020 J/year. diffuse (0.1 W/m2 on So, a small fraction of the Earth’s total heat capacity average) to be would satisfy our needs for many millennia. recoverable. However, the problem is HOW to use this bonanza! So, not much heat diffuses “by itself” to the Earth surface per average. So, how to harness the geothermal energy to be our servant? Easy way: there are some areas where the geothermal activity is much higher than average – where there are hot sources, steam sources, geysers, or lava streams. In such places geothermal energy can be readily utilized. Less easy way: In other locations, geothermal energy has to be mined. Almost everywhere on Earth the geothermal gradient – i.e., the rate of temperature increase with the depth under the Earth surface – has a similar value of ~ 30 ºC /km. So, by drilling a 5 km well one can have very hot water! (150 ºC, or 300 ºF). Let’s begin with the “easy” geothermal energy – we have to tell the story of Earth’s continents, and tectonic plates. There are several major tectonic plates that are in constant motion relative to one another. -

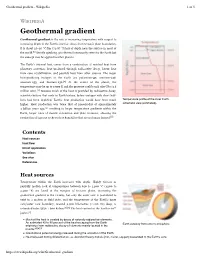

Geothermal Gradient - Wikipedia 1 of 5

Geothermal gradient - Wikipedia 1 of 5 Geothermal gradient Geothermal gradient is the rate of increasing temperature with respect to increasing depth in the Earth's interior. Away from tectonic plate boundaries, it is about 25–30 °C/km (72-87 °F/mi) of depth near the surface in most of the world.[1] Strictly speaking, geo-thermal necessarily refers to the Earth but the concept may be applied to other planets. The Earth's internal heat comes from a combination of residual heat from planetary accretion, heat produced through radioactive decay, latent heat from core crystallization, and possibly heat from other sources. The major heat-producing isotopes in the Earth are potassium-40, uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232.[2] At the center of the planet, the temperature may be up to 7,000 K and the pressure could reach 360 GPa (3.6 million atm).[3] Because much of the heat is provided by radioactive decay, scientists believe that early in Earth history, before isotopes with short half- lives had been depleted, Earth's heat production would have been much Temperature profile of the inner Earth, higher. Heat production was twice that of present-day at approximately schematic view (estimated). 3 billion years ago,[4] resulting in larger temperature gradients within the Earth, larger rates of mantle convection and plate tectonics, allowing the production of igneous rocks such as komatiites that are no longer formed.[5] Contents Heat sources Heat flow Direct application Variations See also References Heat sources Temperature within the Earth -

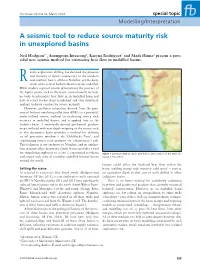

A Seismic Tool to Reduce Source Maturity Risk in Unexplored Basins

first break volume 32, March 2014 special topic Modelling/Interpretation A seismic tool to reduce source maturity risk in unexplored basins Neil Hodgson1*, Anongporn Intawong1, Karyna Rodriguez1 and Mads Huuse2 present a pow- erful new seismic method for estimating heat flow in undrilled basins. ecent exploration drilling has derisked the presence and maturity of Aptian source rock in the northern R and southern basins offshore Namibia, yet the deep- water of the central Luderitz Basin remains undrilled. While modern regional seismic demonstrates the presence of the Aptian source rock in this basin, conventionally we have no tools to interrogate heat flow in an undrilled basin and have to resort to closeology, trendology and even structural- analogy to derive comfort for source maturity. However, geotherm estimation derived from the pres- ence of bottom-simulating reflections (BSR’s) is a powerful, under-utilized seismic method for evaluating source rock maturity in undrilled basins, and is applied here to the Luderitz basin. A seismically derived geothermal gradient map conflated with new depth mapping of the source rock in this deepwater basin provides a method for defining an oil generative window – the ‘Goldilocks Zone’, and constraining source rock maturity (or ‘effectiveness’) risk. This technique is not exclusive to Namibia, and its applica- tion in many other deepwater clastic basins provides a tool for stimulating explorers to create a constrained geotherm Figure 1 Spectrum dataset, basin distribution and location of the wells dis- and source rock atlas of countless undrilled frontier basins cussed in this article. around the world. factors could affect the localized heat flow within the Setting the scene basin, yielding source rock maturity ‘cold spots’ – even at As revealed in a previous First Break article (Hodgson and an equivalent depth to that seen in wells drilled in offset Intawong, FB Dec 2013), recent exploration wells operated (adjacent) basins. -

Geothermal Regime of the World Sedimentary Basins

Geothermal Regime of the World Sedimentary Basins Astakhov S.M.*1 – [email protected] Reznikov A.N.2 1OJSC Krasnodarneftegeophysica, 2Southern Federal University Copyright 2012, SBGf - Sociedade Brasileira de Geofísica Este texto foi preparado para a apresentação no V Simpósio Brasileiro de Geofísica, Salvador, 27 a 29 de novembro de 2012. Seu conteúdo foi revisado pelo Comitê Técnico do V SimBGf, mas não necessariamente representa a opinião da SBGf ou de seus associados. É proibida a reprodução total ou parcial deste material para propósitos comerciais sem prévia autorização da SBGf. ________________________________________________________________________ Resume The type of geothermal regime is considered as the significant attribute influenced on the paleotemperature reconstruction methodology and heat flow analysis especially in basin modeling approach. That is the relevance of this study related with. A number of generalized equations were obtained by detailed studying of the temperature-depth profiles and various geothermal indicators al over the world. Three main "summarizing" groups of factors were identified. These allowed classifying all equations obtained into 3 classes: Anomalous, Normal and Magmatic intrusions influenced geothermal regimes. Introduction The temperature distribution along the section is considered to be the quintessence of the various factors influencing the final accumulation of hydrocarbons (HC). In this mind, the generalization up-to-date studies on the sedimentary basins geothermal regime characteristics are of great interest. Temperature-depth profiles and various geothermal indicators in more than 5,000 wells and measurements were studied. 307 equations that characterize the geothermal regime of the various basins were calculated. Certain features of the temperature profiles and calculated equations were identified. -

Geothermal Favorability Model of Washington State

S E E C R U O S S GEOTHERMAL FAVORABILITY E E MODEL OF WASHINGTON STATE R L by Darrick E. Boschmann, Jessica L. Czajkowski, and A A Jeffrey D. Bowman R R U WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY T T AND EARTH RESOURCES A A N N Open File Report 2014-02 July 2014 GEOTHERMAL FAVORABILITY MODEL OF WASHINGTON STATE by Darrick E. Boschmann, Jessica L. Czajkowski, and Jeffrey D. Bowman WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Open File Report 2014-02 July 2014 DISCLAIMER Neither the State of Washington, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the State of Washington or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the State of Washington or any agency thereof. WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTM ENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Peter Goldmark—Commissioner of Public Lands DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES David K. Norman—State Geologist John P. Bromley—Assistant State Geologist Washington Department of Natural Resources Di vi sion of Geology and Earth Resources Mailing Address: Street Address: MS 47007 -

Potential for Geothermal Energy in Northern Louisiana

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2015 Potential for Geothermal Energy in Northern Louisiana: Analysis of the Subsurface Environment in Union and Morehouse Parishes Tessa Shizuko Hermes Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hermes, Tessa Shizuko, "Potential for Geothermal Energy in Northern Louisiana: Analysis of the Subsurface Environment in Union and Morehouse Parishes" (2015). LSU Master's Theses. 2658. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2658 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POTENTIAL FOR GEOTHERMAL ENERGY IN NORTHERN LOUISIANA: ANALYSIS OF THE SUBSURFACE ENVIRONMENT IN UNION AND MOREHOUSE PARISHES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geology and Geophysics by Tessa Shizuko Hermes B.A., Oberlin College, 2009 December 2015 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisors, Drs. Barb Dutrow and Jeff Nunn, for their support, guidance, and patience throughout this endeavor. Dr. Dutrow was the on-campus representative for my advising team, meeting with me at least once a week to discuss my work, progress, and to answer any questions I might have either in person or via email. -

Analysis of Enhanced Geothermal System Development Scenarios for District Heating and Cooling of the Göttingen University Campus

geosciences Article Analysis of Enhanced Geothermal System Development Scenarios for District Heating and Cooling of the Göttingen University Campus Dmitry Romanov 1,2,3,* and Bernd Leiss 1,2 1 Geoscience Centre, Department of Structural Geology and Geodynamics, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 2 Universitätsenergie Göttingen GmbH, Hospitalstraße 3, 37073 Göttingen, Germany 3 HAWK Hildesheim/Holzminden/Faculty of Resource Management, Göttingen University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Rudolf-Diesel-Straße 12, 37075 Göttingen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: The huge energy potential of Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) makes them perspective sources of non-intermittent renewable energy for the future. This paper focuses on potential scenarios of EGS development in a locally and in regard to geothermal exploration, poorly known geolog- ical setting—the Variscan fold-and-thrust belt —for district heating and cooling of the Göttingen University campus. On average, the considered single EGS doublet might cover about 20% of the heat demand and 6% of the cooling demand of the campus. The levelized cost of heat (LCOH), net Citation: Romanov, D.; Leiss, B. present value (NPV) and CO2 abatement cost were evaluated with the help of a spreadsheet-based Analysis of Enhanced Geothermal model. As a result, the majority of scenarios of the reference case are currently not profitable. Based System Development Scenarios for on the analysis, EGS heat output should be at least 11 MWth (with the brine flow rate being 40 l/s District Heating and Cooling of the and wellhead temperature being 140 ◦C) for a potentially profitable project.