THE SHOT CYCLE: Key Building Block for Situation Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Mixed Doubles

UNITED STATES COURT TENNIS ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT 2008 - 2009 2008-2009 Annual Report Table of Contents President’s Report ..................................................................2-3 Board of Governors..................................................................4-7 Annual Awards ............................................................................... 8 History of the USCTA ....................................................................... 9 Financial Report 2008-2009 ....................................................... 10-11 Treasurer’s Report ............................................................................. 12 Tournament Play Guidelines ............................................................... 13 Bylaws ............................................................................................ 14-15 United States Court Tennis Preservation Foundation ...................... 16-17 Feature: Junior Tennis On The Rise ................................................... 18-23 Club Reports .................................................................................... 24-34 Top 25 U.S. Amateurs ............................................................................ 35 Tournament Draws .......................................................................... 36-49 Feature: The 2009 Ladies’ World Championship .............................. 50-53 Record of Champions ..................................................................... 54-62 Presidents ......................................................................................... -

Tennis Study Guide

TENNIS STUDY GUIDE HISTORY Mary Outerbridge is credited with bringing tennis to America in the mid-1870’s by introducing it to the Staten Island Cricket and Baseball Club. In 1880 the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) was established, Lawn was dropped from the name in the 1970’s and now go by (USTA). Tennis began as a lawn sport, but later clay, asphalt and concrete became more standard surfaces. The four most prestigious World tennis tournaments include: the U.S. Open, Australian Open, French Open, and Wimbledon . In 1988, tennis became an official medal sport. Tennis can be played year round, is low in cost, and needs only two or four players; it is also suitable for all age groups as well as both sexes. EQUIPMENT The only equipment needed to play tennis consists of a racket, a can of balls, court shoes and clothing that permits easy movement. The most important tip for beginners to remember is to find a racket with the right grip. The net hangs 42 inches high at each post and 36 inches high at the center. RULES The game starts when one person serves from anywhere behind the baseline to the right of the center mark and to the left of the doubles sideline. The server has two chances to serve legally into the diagonal service court. Failure to serve into the court or making a serving fault results in a point for the opponents. The same server continues to alternate serving courts until the game is finished, and then the opponent serves. -

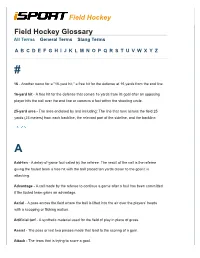

Field Hockey Glossary All Terms General Terms Slang Terms

Field Hockey Field Hockey Glossary All Terms General Terms Slang Terms A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z # 16 - Another name for a "16-yard hit," a free hit for the defense at 16 yards from the end line. 16-yard hit - A free hit for the defense that comes 16 yards from its goal after an opposing player hits the ball over the end line or commits a foul within the shooting circle. 25-yard area - The area enclosed by and including: The line that runs across the field 25 yards (23 meters) from each backline, the relevant part of the sideline, and the backline. A Add-ten - A delay-of-game foul called by the referee. The result of the call is the referee giving the fouled team a free hit with the ball placed ten yards closer to the goal it is attacking. Advantage - A call made by the referee to continue a game after a foul has been committed if the fouled team gains an advantage. Aerial - A pass across the field where the ball is lifted into the air over the players’ heads with a scooping or flicking motion. Artificial turf - A synthetic material used for the field of play in place of grass. Assist - The pass or last two passes made that lead to the scoring of a goal. Attack - The team that is trying to score a goal. Attacker - A player who is trying to score a goal. -

ERSTE BANK OPEN: DAY 5 MEDIA NOTES Friday, October 23, 2015

ERSTE BANK OPEN: DAY 5 MEDIA NOTES Friday, October 23, 2015 Wiener Stadthalle, Vienna, Austria | October 19-25, 2015 Draw: S-32, D-16 | Prize Money: €1,745,040 | Surface: Indoor Hard ATP Info: Tournament Info: ATP PR & Marketing: www.ATPWorldTour.com www.erstebank-open.com Martin Dagahs: [email protected] @ATPWorldTour facebook.com/ErsteBankOpenVienna Fabienne Benoit: [email protected] facebook.com/ATPWorldTour Press Room: +43 1 98100578 ANDERSON NEARS 1,000 ACES; FOGNINI SEEKS 1ST WIN OVER FERRER QUARTER-FINAL PREVIEW: Storylines abound in Friday’s Erste Bank Open semi-finals. No. 2 seed Kevin Anderson, who has already clinched a career-high 44 wins in 2015, could surpass 1,000 aces on the season against unseeded American Steve Johnson. The ATP World Tour’s ace leader, No. 7 seed Ivo Karlovic, meets a resurgent Ernests Gulbis, who is seeking his first semi- final appearance of the season. Also playing for his first semi in over a year is Lukas Rosol, who looks to build off his upset of No. 4 seed Jo-Wilfried Tsonga with another of No. 6 seed Gael Monfils. No. 1 seed David Ferrer takes an 8-0 FedEx Head 2 Head record (17-2 in sets) against No. 8 seed Fabio Fognini into their quarter-final match. The in-form Italian Fognini won the Australian Open doubles title with countryman Simone Bolelli and has posted strong singles results late in the season, just as his fiancée Flavia Pennetta is doing on the women’s tour. Fognini watched from Arthur Ashe Stadium as Pennetta captured the US Open title on Sept. -

Wimbledon Wordsearch

WORKSHEET WIMBLEDON WORDSEARCH WARM UP 1 1. ball 11. Gordon Reid 2. ace 12. Novak Djokovic Name 3. volley 13. Rafael Nadal 4. baseline 14. Dominic Thiem Score 5. match 15. Roger Federer Firstly try to find as many tennis words in the wordsearch 6. net 16. Jordanne Whiley as you can (numbers 1-10). Score 1 point for each one. 7. rally 17. Ashleigh Barty Then try to find the ten famous tennis players’ surnames (11-20). Score 2 points for each one of these you find. 8. court 18. Simona Halep 9. deuce 19. Karolina Pliskova 10. lob 20. SofiaKenin NINEKREREDEF YWGJUMBRYCMB ETBALLETZAVO LEACVIRXTHML INDLDAJCCAEN HHFHBLHGHLIY WDJOKOVICEHE ERHBPECAJPTL CAPLISKOVAYL ULDGTCOURTUO ELXHYILADANV DYIMENILESAB WORKSHEET DESIGNER TENNIS TOWEL WARM UP 2 Name Design an exciting, amusing, colourful tennis towel! Be imaginative! You don’t even need to make your towel rectangular. WORKSHEET DESIGNER TENNIS MUG WARM UP 2 Name Design a mug to give someone a taste of tennis! E.g. balls, rackets, courts, strawberries, grass, etc. WORKSHEET HAWK EYE Find your way around Wimbledon WARM UP 3 Name Using one of the maps of Wimbledon, answer the following questions: 1 Write the coordinates for: Centre Court Number 1 Court Number 2 Court The Millennium Building 2 Give directions from Gate 5 to Court Number 16 3 Give directions from Murray Mount to the new Number 2 Court: 4 Where can you find the toilets? Give all the coordinates: 5 On the back of this page, write down a route in the grounds, for a visitor to Wimbledon to take. -

The Ballad of Kiss My Ace!

The Ballad of “Kiss My Ace”- A Women’s USTA 2.5 tennis team- Club Fit Briarcliff Westchester, Ny If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster, And treat those two impostors just the same By Jeff Scott- Club Fit Pro and 2012 Team Coach A Floating Ball was coming down our Southern “Ace” team’s “heartland” of the tennis court, during our match point for the deciding and final match of the Eastern Sectional Championship tournament. Marcie lunged for it with her backhand two-fisted volley, and steered the ball deep into the home Northern team’s heartland, apparently smack on the baseline! A simultaneous shriek of joy erupted from both Jodi and Marcie, as the match was hard fought, close as can be and deep into the super tiebreak. After all, it was a competition against the team that had clinched the tournament and was heading off to vie for the National Title. The win against the tournament champion certainly would have been gratifying, and would have catapulted the Southern Aces into second place, a very respectable finish to a Cinderella season by unified and determined group of Westchester tennis warrior women! But no! Defeat was snatched from the jaws of victory by the most unlikely of sources- a defiant finger wagged in the air! With an air of duplicity, an admonition and an over-rule were issued simultaneously with one, exultation stealing gesture. The infamous finger belonged not to one of the Northern’s opponents, but to a one of the few local officials assigned to monitor the tournament. -

This Content Is a Part of a Full Book - Tennis for Students of Medical University - Sofia

THIS CONTENT IS A PART OF A FULL BOOK - TENNIS FOR STUDENTS OF MEDICAL UNIVERSITY - SOFIA https://polis-publishers.com/kniga/tenis-rukovodstvo-za-studenti/ A brief history of tennis 1. Origin and development of the game Ball games were popular in ancient Rome and Greece under the name of a spherical "ball game". In the 11 th and 12 th centuries, the games of "Jacko del Palone" and "Jaco de la Corda" were mentioned, which resembled modern tennis (Todorov 2010; Mashka, Shaffarjik 1989). In the 14 th century, outdoor and indoor courts started to be built in France, where the game of "court – tennis" was played, which was later renamed "palm game", that, dependent on being played inside or outside, was called "short tennis" and " long tennis" (Penchev 1989). Antonio Scaino da Salò’s book "Treatise on the game of the ball" (1555) describes the game instruments - a racquet and a ball - a tight ball of wool, wrapped in leather. It was struck with the palm of the hand, wrapped in a leather belt and a wooden case. A glove was used as well to protect against pain and traumas (Mashka, Shaffarjik 1989). The "court - tennis" game became popular predominantly amongst the nobles in Europe under the name of "Jeu de paume" – palm game, played both indoors and outdoors. “Mirabo” hall, part of the famous Versailles Palace that was transformed at that time by the Sun King - Louis XIV into a main residence of the French kings, exists to this day and had served for that purpose. Fig. 1. -

THE ACE BENCHVARMER Lora Grandrath (Assignment: Yrite A

THE ACE BENCHVARMER Lora Grandrath (Assignment: Yrite a comparison of two coaches, teachers, or bosses you have had in order to define what for you is the essence of good coaching, teaching or managing.) ( 1) "My name is Shelly Freeman George--just call me Shelly--and I'm going to be the new tennis coach here at City High. Before I tell you a little about myself, let me start out by sending a clipboard around. On the sheet, I want you to write your name, grade, phone number, and all your tennis experience. That includes how many years you've taken lessons, varsity experience and letters you've won," directed the woman of about twenty-seven years. (2) "Okay, now I'll give you a little background information on myself," she said, after handing the clipboard to the girl on her right. "I grew up here in Iowa City and I too attended City High School. I then went on to play tennis at St. Ambrose College but later transferred to University of Iowa where I continued to play and eventually graduated. My husband, my little girl, and I now live here in Iowa City. My husband and I own Cedar Valley Tree Service, which he runs. I am U.S.T.A. (United States Tennis Association) certified, Vice-President of the NJTL (National Junior Tennis League) chapter here in Iowa City, and I am also a certified rater of the Volvo Tennis League. (3) The clipboard eventually wound its way to me. I glanced at the names and information already written down; I didn't like what I saw. -

Federer Retains Hopman Title

SUNDAY, JANUARY 6, 2019 16 Pakistan avoid innings defeat, delay South Africa Bahrain snatch victory charge draw with UAE Mohamed Al Rohaimi’s goal salvages draw for Bahrain in 2019 Asian Cup opener AFP | Abu Dhabi osts United Arab Emir- Pakistan’s Shan Masood plays a shot ates salvaged a contro- Hversial 1-1 draw in their AFP | Cape Town, South Africa overs was not worth it,” said Asian Cup curtain-raiser against South African fast bowler Kag- Bahrain yesterday. lthough Pakistan are fac- iso Rabada. Substitute Ahmed Khalil Aing a heavy defeat, their Masood hit a composed 61 smashed home a late penalty fightback on the third day of and Shafiq and Azam both harshly awarded for a handball the second Test against South played aggressively to score after Mohamed Alromaihi had Africa was a good sign for the 88 and 72 respectively. given Bahrain a shock lead in team, batsman Asad Shafiq Masood and Shafiq shared Abu Dhabi. said yesterday. the most enterprising part- The Emirates scored after just Half-centuries by Shafiq, nership of the match when 14 seconds when the two teams Shan Masood and Babar Azam they put on 132 in 132 min - met at the 2015 Asian Cup in enabled Pakistan to take the utes off 168 balls for the third Australia but there was little match into a fourth day. wicket. danger of that in a scruffy first Pakistan were bowled out Shafiq said a positive mind- half. in the last over for 294, leav- set was the key to Pakistan’s UAE’s Ismail Alhammadi fired ing South Africa needing 41 best day of the series. -

Tennis Courts: a Construction and Maintenance Manual

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 677 EF 005 376 TITLE Tennis Courts: A Construction and Maintenance Manual. INSTITUTION United States Tennis Court & Track Builders Association.; United States Tennis Association. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 246p.; Colored photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM U.S. Tennis Court & Track Builders Association, 3525 Ellicott Mills Dr., Suite N., Ellicott City, MD 21043-4547. Tel: 410-418-4800; Fax: 410-418-4805; Web site: <http://www.ustctba.com>. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) -- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Construction (Process); *Facility Guidelines; Facility Improvement; Facility Planning; *Maintenance; *Tennis IDENTIFIERS *Athletic Facilities ABSTRACT This manual addresses court design and planning; the construction process; court surface selection; accessories and amenities; indoor tennis court design and renovation; care and maintenance tips; and court repair, reconstruction, and renovation. General and membership information is provided on the U.S. Tennis Court and Track Builders Association and the U.S. Tennis Association, along with lists of certified tennis court builders and award winning tennis courts from past years. Numerous design and layout drawings are also included, along with Tennis Industry Magazine's maintenance planner. Sources of information and a glossary of terms conclude the manual. (GR) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made -

Selected Tennis and Badminton Articles. Sports Articles Reprint Series

DOCUMENT EESUn ED 079 313 SP 006 734 AUTHOR Tyler, Jo Ann, Ed. TITLE Selected Tennis and Badminton Articles. Sports Articles Reprint Series. Third Edition. INSTITUTION AmericaL Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, Washington, D.C. Div. for Girls and Women's Sports. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 128p. AVAILABLE FROMAmerican Association for Health, Physical Educ-+ion, and Recreation, 1201 16th St., N. W., Washingt_ D. C. 20036 ($1.25) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Athletic Activities; *Athletics; *Exercise (Physiology); *Physical Activities; *Physical Education; Womens Education IDENTIFIERS Tennis and Badminton ABSTRACT Presented is a collection of articles from "The Division for Girls and Women's Sports (DGWS) Guides 1964-1970," "Research Quarterly 1962-1969," and "Journal of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, 1962-1969." It is the latest inthe American Association for Health, Physical Education, andRecreation "AAHPER's Sports Articles Reprint Series,"a special prcject cf the Publications Area, DGWS. This is the third edition of ',Selected Tennis and Badminton Articles." (Author) SPORTS ARTICLES REPRINT SERIES r7s Selected cz)Tennis and Badminton Articles U S DEPARTIW.NT OF HEALTH EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED F PON, THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OP POLICY This collection of articles from DG WS Guides 1964-1970, Research Quarterly 1962-1969, and Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, 1962-1969 is the latest in AAMPER's Sports Articles Reprint Series, a special project of the Publications Area, Division for Girls and Women's Sports. -

Australian Open and WOWOW Ace Landmark Broadcasting Deal in Japan

Wednesday 26 October 2016 Australian Open and WOWOW ace landmark broadcasting deal in Japan Tennis Australia and Japanese broadcaster WOWOW announced today a significant extension and expansion of their long-term broadcast relationship to 2021. Commencing January 2017, the new deal is Tennis Australia’s largest broadcast agreement in Japan. Along with extensive coverage of the Australian Open, WOWOW will for the first time broadcast matches from the Emirates Australian Open Series, including: ・ Mastercard Hopman Cup, Perth ・ Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (men’s matches) ・ Apia International Sydney (men’s matches) ・ World Tennis Challenge, Adelaide ・ Australian Open Junior Championships, Wheelchair Championships and Legends event “We are very pleased to not just continue, but extend and expand our long-standing partnership with WOWOW in broadcasting four weeks of world class tennis,” Tennis Australia CEO Craig Tiley said. “As the Grand Slam of Asia Pacific our fans in Japan treat the Australian Open as their ‘home’ slam, and we are delighted with WOWOW’s commitment to their most comprehensive coverage of the Australian summer of tennis. Our Japanese fans will now be able to follow the action right across Australia throughout January. “With more channels, content and live feed capabilities, we will be able to tell a more compelling story that shows the power, passion and glory of tennis.” WOWOW Board Director, Tsutomu Makino said, “With this renewal till 2021, Tennis Australia (TA) and WOWOW’s broadcast relationship will span 30 years. We are very pleased to further foster and cement our long term partnership between TA and WOWOW. The new deal commencing in 2017 will enable us to offer the largest media rights exploitation on WOWOW’s platforms across a broad range of tennis content, including events around a Grand Slam.” “We offer various entertainment features beyond existing television broadcast.