Regional Anesthesia in the Patient Receiving Antithrombotic Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: the Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril

Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril Michael Matheny, Sonoo Thadaney Israni, Mahnoor Ahmed, and Danielle Whicher, Editors WASHINGTON, DC NAM.EDU PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE • 500 Fifth Street, NW • WASHINGTON, DC 20001 NOTICE: This publication has undergone peer review according to procedures established by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM). Publication by the NAM worthy of public attention, but does not constitute endorsement of conclusions and recommendationssignifies that it is the by productthe NAM. of The a carefully views presented considered in processthis publication and is a contributionare those of individual contributors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the authors’ organizations; the NAM; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data to Come Copyright 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Suggested citation: Matheny, M., S. Thadaney Israni, M. Ahmed, and D. Whicher, Editors. 2019. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril. NAM Special Publication. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs “Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.” --GOETHE PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs ABOUT THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE The National Academy of Medicine is one of three Academies constituting the Nation- al Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The Na- tional Academies provide independent, objective analysis and advice to the nation and conduct other activities to solve complex problems and inform public policy decisions. -

Sports Medicine Examination Outline

Sports Medicine Examination Content I. ROLE OF THE TEAM PHYSICIAN 1% A. Ethics B. Medical-Legal 1. Physician responsibility 2. Physician liability 3. Preparticipation clearance 4. Return to play 5. Waiver of liability C. Administrative Responsibilities II. BASIC SCIENCE OF SPORTS 16% A. Exercise Physiology 1. Training Response/Physical Conditioning a.Aerobic b. Anaerobic c. Resistance d. Flexibility 2. Environmental a. Heat b.Cold c. Altitude d.Recreational diving (scuba) 3. Muscle a. Contraction b. Lactate kinetics c. Delayed onset muscle soreness d. Fiber types 4. Neuroendocrine 5. Respiratory 6. Circulatory 7. Special populations a. Children b. Elderly c. Athletes with chronic disease d. Disabled athletes B. Anatomy 1. Head/Neck a.Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 2. Chest/Abdomen a.Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 3. Back a.Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation 1 d. Vascular 4. Shoulder/Upper arm a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 5. Elbow/Forearm a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 6. Hand/Wrist a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 7. Hip/Pelvis/Thigh a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 8. Knee a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 9. Lower Leg/Foot/Ankle a. Bone b. Soft tissue c. Innervation d. Vascular 10. Immature Skeleton a. Physes b. Apophyses C. Biomechanics 1. Throwing/Overhead activities 2. Swimming 3. Gait/Running 4. Cycling 5. Jumping activities 6. Joint kinematics D. Pharmacology 1. Therapeutic Drugs a. Analgesics b. Antibiotics c. Antidiabetic agents d. Antihypertensives e. -

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 1

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 1 and hepatic pathology. The rotation consists of daily interpretation of Pathology and subspecialty biopsies, participation in subspecialty conferences, slide set study, and assigned readings. Students participate in their own Laboratory Medicine learning by setting their rotation objectives with faculty at the start of their elective and following through with a schedule of clinical, laboratory and core lecture conferences. Students will need to obtain the appropriate Pathologists play many roles in medicine, from interpreting surgical staff members' permission for the rotation as follows: dermatopathology biopsies to supervising clinical laboratory testing. It has been estimated (Garth Fraga); neuropathology (Kathy Newell); renal pathology (Timothy that 70% of all medical decisions are based on data generated by Fields); breast pathology (Fang Fan); hepatic pathology (Maura O'Neil). pathology departments. The department of Pathology and Laboratory Prerequisite: Completion of the core clinical clerkships and permission of Medicine at KUMC plays an integral role in the core curriculum and also the faculty. LEC. offers elective courses to medical students interested in learning more about laboratory practice. Students in elective rotations participate in daily teaching conferences and specimen “sign-out” at the University of Kansas Hospital. They receive hands-on exposure to pathology technical methodology in the surgical pathology suite, cytopathology and hematopathology. PAON 920. Molecular Medicine: Approaches & Ethics. 2 Hours. Molecular Medicine: Approaches Ethics is a two semester course for first year MD-PhD students taught by the Director of the MD- PhD Program, with other faculty from the basic science and clinical departments. Through lectures, small group discussion, online modules, evaluation of primary literature, and presentations/discussions with current KUMC faculty, students will be introduced to the process of scientific investigation. -

DUKE UNIVERSITY School of Medicine Pathologists' Assistant

DUKE UNIVERSITY School of Medicine Pathologists’ Assistant Program Department of Pathology Academic Programs The Department of Pathology at Duke University offers a wide array of training programs to fit individual requirements and goals. The Residency Training program is an ACGME approved program and is available as an Anatomic Pathology/Clinical Pathology combined program, a shorter Anatomic Pathology only program, or an Anatomic Pathology/Neuropathology program. Subspecialty fellowships in Cytopathology, Dermatopathology, Hematopathology, Medical Microbiology, and Neuropathology are also ACGME approved. These programs provide the highest quality of graduate medical education by drawing on the depth and breadth of faculty expertise in the Department in all aspects of anatomic and clinical pathology and the availability of a wide variety of often complex clinical cases seen at Duke University Health System. For medical students interested in a career in Pathology pre-doctoral fellowships, internships and externships are available. Research Training in Experimental pathology can be obtained through Pre- and postdoctoral fellowships of one to five years. All pre-doctoral fellows are candidates for the Ph.D. degree in pathology. The Ph.D. is optional in postdoctoral programs, which provide didactic and research training in various aspects of modern experimental pathology. A two year NAACLS accredited Pathologists’ Assistant Program leads to a Master of Health Science degree, certifies graduates to sit for the ASCP Board of Certification examination, and leads to exciting career opportunities in a variety of anatomic pathology laboratory settings. Pathologists’ assistants are analogous to physician assistants, but with highly specialized training in autopsy and surgical pathology. This profession was pioneered in the Duke Department of Pathology 50 years ago, and is one of only twelve such programs in existence today. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Acute Pain Medicine & Regional Anesthesia Course

4TH ANNUAL Carlo D. Franco, MD COURSE DESCRIPTION Chairman Regional Anesthesia ACUTE PAIN MEDICINE & The Acute Pain Medicine & Regional Anesthesia Course JHS Hospital of Cook County provides an intense, hands-on cadaver workshop for civilian Professor of Anesthesiology and Anatomy and military physician anesthesiologists seeking to add Rush University Medical Center – Chicago, IL REGIONAL ANESTHESIA advanced anesthesia techniques to his/her practice. The workshop focuses on indications, anatomical considerations Ralf E. Gebhard, MD Professor of Anesthesiology COURSE and techniques for each block. Participants will work in small Associate Professor of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation groups directly with renowned faculty during the hands- Director, Division of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Perioperative Pain Management FOR MILITARY AND CIVILIAN ANESTHESIOLOGISTS on instruction with non-embalmed cadaver specimens at multiple workstations in a state-of-the-art anatomical teaching Miller School of Medicine INTERESTED IN TRAUMA AND PERIOPERATIVE laboratory. Participants will conduct actual ultrasound guided University of Miami – Miami, FL PAIN MANAGEMENT regional techniques on the aforementioned cadavers. This Harold Gelfand, MD course was formerly the Annual Comprehensive Regional Regional Anesthesia/Acute Pain Medicine Anesthesia Workshop, held for 10 years at the Uniformed Bethesda, MD Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Maryland. Roy Greengrass, MD Professor of Anesthesiology COURSE OBJECTIVES Mayo Clinic – Jacksonville, FL 1. Participants will review multimodal analgesia including Justin W. Heil, MD MARCH 18-19, 2016 various opioid and non-opioid agents utilized in the setting of Regional Anesthesia/Acute Pain Medicine BALTIMORE, MARYLAND acute pain. San Diego, CA 2. Participants will be able to identify the organization and fiscal concerns of an acute pain medicine service. -

2020 Pain Medicine MOC Content Outline

ABA Pain Medicine Examination CONTENT OUTLINE THE AMERICAN BOARD OF ANESTHESIOLOGY 4208 Six Forks Road, Suite 1500 | Raleigh, NC 27609-5765 | Phone: (866) 999-7501 | Fax: (866) 999-7503 | Website: www.theABA.org Pain Medicine Content Outline Updated January 2015 1. General ………………………………………………………………………………….…………....……… 2 2. Assessment and Psychology of Pain ………………………………………………………………………3 3. Treatment of Pain: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse effects, drug interactions, and indications/contraindications……………………………………………………………………..… ……….5 4. Treatment of Pain: Other Methods ……………………………………………..…………………………..6 5. Clinical States: Taxonomy ………………………………………………....………………………………..8 6. Tissue Pain ……………………………………………....………………………………………….………..8 7. Visceral Pain …………………………………………………………………………..…………………….11 8. Headache and Facial Pain ……………………………………………………………………...…………12 9. Nerve Damage ……………………………………………………………………………………….……. 12 10. Special Cases ……………………………………………………………………………………………….13 1 1. General 1. Anatomy and Physiology: Mechanisms of Nociceptive Transmission 1. Peripheral mechanisms 2. Central mechanisms: spinal and medullary dorsal horns 3. Central mechanisms: segmental and brain stem 4. Central mechanisms: thalamocortical 5. Other-General: Anatomy and physiology 2. Pharmacology of Pain Transmission and Modulation 1. Experimental models: limitations 2. Peripheral mechanisms of pain transmission and modulation 3. Synaptic transmission of pain in the dorsal horn 4. Central sensitization: mechanisms and implications for treatment of pain 5. Neurotransmitters -

2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats*

VETERINARY PRACTICE GUIDELINES 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats* Tamara Grubb, DVM, PhD, DACVAAy, Jennifer Sager, BS, CVT, VTS (Anesthesia/Analgesia, ECC)y, James S. Gaynor, DVM, MS, DACVAA, DAIPM, CVA, CVPP, Elizabeth Montgomery, DVM, MPH, Judith A. Parker, DVM, DABVP, Heidi Shafford, DVM, PhD, DACVAA, Caitlin Tearney, DVM, DACVAA ABSTRACT Risk for complications and even death is inherent to anesthesia. However, the use of guidelines, checklists, and training can decrease the risk of anesthesia-related adverse events. These tools should be used not only during the time the patient is unconscious but also before and after this phase. The framework for safe anesthesia delivered as a continuum of care from home to hospital and back to home is presented in these guidelines. The critical importance of client commu- nication and staff training have been highlighted. The role of perioperative analgesia, anxiolytics, and proper handling of fractious/fearful/aggressive patients as components of anesthetic safety are stressed. Anesthesia equipment selection and care is detailed. The objective of these guidelines is to make the anesthesia period as safe as possible for dogs and cats while providing a practical framework for delivering anesthesia care. To meet this goal, tables, algorithms, figures, and “tip” boxes with critical information are included in the manuscript and an in-depth online resource center is available at aaha.org/anesthesia. (J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2020; 56:---–---. DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7055) AFFILIATIONS Other recommendations are based on practical clinical experience and From Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman, a consensus of expert opinion. -

The History of Medicine a Beginner’S Guide

The History of Medicine A Beginner’s Guide Mark Jackson A Oneworld Paperback Published in North America, Great Britain & Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Mark Jackson 2014 The right of Mark Jackson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-520-6 eISBN 978-1-78074-527-5 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com For Ciara, Riordan and Conall ‘A heart is what a heart can do.’ Sir James Mackenzie, 1910 Contents List of illustrations viii Preface x Introduction xiii 1 Balance and flow: the ancient world 1 2 Regimen and religion: medieval medicine 25 3 Bodies and books: a medical Renaissance? 50 4 Hospitals and hope: the Enlightenment 84 5 Science and surgery: medicine in the nineteenth century 120 6 War and welfare: the modern world 159 Conclusion 197 Timeline 201 Further reading 214 Index 221 List of illustrations Figure 1 Chinese acupuncture chart Figure 2 Vessel for cupping (a form of blood-letting) discov- ered in Pompeii, dating from the first century CE Figure 3 Text and illustration on ‘urinomancy’ or urine analysis Figure 4 Mortuary crosses placed on the bodies of plague victims, c. -

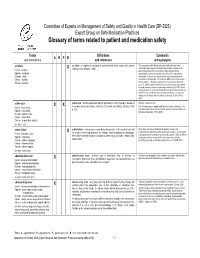

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine for Students, by Students

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine For Students, By Students By Patrick Wu, DO, MPH and Jonathan Siu, DO ® Second Edition Updated April 2015 Copyright © 2015 ® No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine 5550 Friendship Boulevard, Suite 310 Chevy Chase, MD 20815-7231 Visit us on Facebook Please send any comments, questions, or errata to [email protected]. Cover Photos: Surgeons © astoria/fotolia; Students courtesy of A.T. Still University Back to Table of Contents Table of Contents Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Myth or Fact?....................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 1: What is a DO? .............................................................................................................................. -

Pathology: a Career in Medicine the Study of the Nature of Disease, Its Causes, Processes, Development, and Consequences

PATHOLOGY A Career in Medicine The Intersociety Council for Pathology Information (ICPI) www.pathologytraining.org 2015 Pathology: A Career in Medicine The study of the nature of disease, its causes, processes, development, and consequences. Pathology is the medical specialty that provides a scientific foundation for medical practice The pathologist is a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and management of human disease by laboratory methods. Pathologists function in three broad areas: as diagnosticians, as teachers, and as investigators. Fundamental to the discipline of pathology is the need to integrate clinical information with physiological, biochemical and molecular laboratory studies, together with observations of tissue alterations. Pathologists in hospital and clinical laboratories practice as consultant physicians, developing and applying knowledge of tissue and laboratory analyses to assist in the diagnosis and treatment of individual patients. As teachers, they impart this knowledge of disease to their medical colleagues, to medical students, and to trainees at all levels. As scientists, they use the tools of laboratory science in clinical studies, disease models, and other experimental systems, to advance the understanding and treatment of disease. Pathology has a special appeal to those who enjoy solving disease-related problems, using technologies based upon fundamental sciences ranging from biophysics to molecular genetics, as well as tools from the more traditional disciplines of anatomy, biochemistry, pharmacology, physiology and microbiology. The Pathologist in Patient Care The pathologist uses diagnostic and screening tests to identify and interpret the changes that characterize different diseases in the cells, tissues, and fluids of the body. Anatomic pathology involves the analysis of the A biosample robot prepares specimens for gross and microscopic structural changes caused by testing disease in tissues and cells removed during biopsy procedures, in surgery, or at autopsy.