Printed Image Digitised by the University of Southampton Library Digitisation Unit Fall in Box Office Income

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Ballet Charity Gala

BRITISH BALLET CHARITY GALA HELD AT ROYAL ALBERT HALL on Thursday Evening, June 3rd, 2021 with the ROYAL BALLET SINFONIA The Orchestra of Birmingham Royal Ballet Principal Conductor: Mr. Paul Murphy, Leader: Mr. Robert Gibbs hosted by DAME DARCEY BUSSELL and MR. ORE ODUBA SCOTTISH BALLET NEW ADVENTURES DEXTERA SPITFIRE Choreography: Sophie Laplane Choreography: Matthew Bourne Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Gran Partita and Eine kleine Nachtmusik Music: Excerpts from Don Quixote and La Bayadère by Léon Minkus; Dancers: Javier Andreu, Thomas Edwards, Grace Horler, Evan Loudon, Sophie and The Seasons, Op. 67 by Alexander Glazunov Martin, Rimbaud Patron, Claire Souet, Kayla-Maree Tarantolo, Aarón Venegas, Dancers: Harrison Dowzell, Paris Fitzpatrick, Glenn Graham, Andrew Anna Williams Monaghan, Dominic North, Danny Reubens Community Dance Company (CDC): Scottish Ballet Youth Exchange – CDC: Dance United Yorkshire – Artistic Director: Helen Linsell Director of Engagement: Catherine Cassidy ENGLISH NATIONAL BALLET BALLET BLACK SENSELESS KINDNESS Choreography: Yuri Possokhov THEN OR NOW Music: Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8 by Dmitri Shostakovich, by kind permission Choreography: Will Tuckett of Boosey and Hawkes. Recorded by musicians from English National Music: Daniel Pioro and Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber – Passacaglia for solo Ballet Philharmonic, conducted by Gavin Sutherland. violin, featuring the voices of Natasha Gordon, Hafsah Bashir and Michael Dancers: Emma Hawes, Francesco Gabriele Frola, Alison McWhinney, Schae!er, and the poetry of -

Prospectus 2 About Us Rambert School, Is Recognised Internationally As One of the Small Group of First-Level Professional Dance Schools of the World

Director: Ross McKim MA PhD NBS (IDP) Patrons: Lady Anya Sainsbury CBE Robert Cohan CBE Prospectus 2 About Us Rambert School, is recognised internationally as one of the small group of first-level professional dance schools of the world. In order to remain so, and to support its students (given the demands they must confront), Rambert School provides a contained, bordered and protected environment through which an unusual and intense level of energy and professionalism is created, respected, treasured and sustained. “Rambert School is a place of education and training in Ballet, Contemporary Dance and Choreography. It seeks to cause or allow each student to achieve his or her unique potential personally and professionally. It encourages learning, reflection, research and creative discovery. Through these processes, as they relate to performance dance, all those at the school are provided with the opportunity to develop their vision, awareness, knowledge and insight into the world and the self. They may thus advance in terms of their art form and their lives.” Principal and Artistic Director Dr Ross McKim MA PhD NBS (IDP) Conservatoire for Dance and Drama Clifton Lodge, St Margaret’s Drive, Twickenham TW1 1QN Telephone: 020 8892 9960 Fax: 020 8892 8090 Mail: [email protected] www.rambertschool.org.uk 3 History Marie Rambert began teaching in London in 1919. In her autobiography she wrote, “In 1920 I collected the various pupils I had into a class and began teaching professionally.” This was the beginning of Rambert School which, in these early days, was based at Notting Hill Gate. Out of it grew Rambert Dance Company. -

The Royal Ballet Present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth Macmillan's

February 2019 The Royal Ballet present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth MacMillan’s dramatic masterpiece at the Royal Opera House Tuesday 26 March – Tuesday 11 June 2019 | roh.org.uk | #ROHromeo Matthew Ball and Yasmine Naghdi in Romeo and Juliet. © ROH, 2015. Photographed by Alice Pennefather Revival features a host of debuts from across the Company, including Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell, Anna Rose O’Sullivan, William Bracewell, Marcelino Sambé and Reece Clarke. Principal dancer with American Ballet Theater, David Hallberg makes his debut in this production as Romeo opposite Natalia Osipova as Juliet. Production relayed live to cinemas and on Tuesday 11 June 2019. This Spring, The Royal Ballet revives Kenneth MacMillan’s 20th-century dramatic masterpiece, Romeo and Juliet. Set to Sergey Prokofiev’s seminal score, the ballet contrasts romantic pas de deux with a series For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media of vibrant ensemble scenes, set against the backdrop of 16th-century Verona as evoked by Nicholas Georgiadis’s designs. A work which has been performed by The Royal Ballet more than 400 times since it was premiered at Covent Garden in 1965, Romeo and Juliet is a classic of the 20th-century ballet repertory, and showcases the dramatic ability of the Company, as well as incorporating a plethora of MacMillan’s signature challenging choreography. During the course of this revival, Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell and Anna Rose O’Sullivan debut as Juliet. Also performing the role during this run are Principal dancers Francesca Hayward, Sarah Lamb and Marianela Nuñez. -

SF Ballet Frankenstein February 2017

2017 Season Infinite Worlds PROGRAM 03 Frankenstein “ City National helps keep my financial life in tune.” So much of my life is always shifting; a different city, a different piece of music, a different ensemble. I need people who I can count on to help keep my financial life on course so I can focus on creating and sharing the “adventures” of classical music. City National shares my passion and is instrumental in helping me bring classical music to audiences all over the world. They enjoy being a part of what I do and love. That is the essence of a successful relationship. City National is The way up® for me. Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor, Educator and Composer Hear Michael’s complete story at cnb.com/Tuned2SF Find your way up.SM Call (866) 618-5242 to learn more. 17 City National Bank 17 City National 0 ©2 City National Personal Banking CNB MEMBER FDIC February 2017 Volume 94, No. 4 Table of Contents PROGRAM Paul Heppner Publisher Susan Peterson 03 Design & Production Director PAGE 26 Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Shaun Swick, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Design 5 Greetings from the Artistic Director 41 Sponsor & Donor News Mike Hathaway Sales Director & Principal Choreographer 44 Great Benefactors Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed, Rob Scott 7 History of San Francisco Ballet San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives 45 Artistic Director’s Council Brieanna Bright, 9 Board of Trustees Joey Chapman, Ann Manning Endowment Foundation Board 46 Season Sponsors Seattle Area Account Executives Jonathan Shipley 11 For Your Information -

September 4, 2014 Kansas City Ballet New Artistic Staff and Company

Devon Carney, Artistic Director FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.444.0052 [email protected] For Tickets: 816.931.2232 or www.kcballet.org Kansas City Ballet Announces New Artistic Staff and Company Members Grace Holmes Appointed New School Director, Kristi Capps Joins KCB as New Ballet Master, and Anthony Krutzkamp is New Manager for KCB II Eleven Additions to Company, Four to KCB II and Creation of New Trainee Program with five members Company Now Stands at 29 Members KANSAS CITY, MO (Sept. 4, 2014) — Kansas City Ballet Artistic Director Devon Carney today announced the appointment of three new members of the artistic staff: Grace Holmes as the new Director of Kansas City Ballet School, Kristi Capps as the new Ballet Master and Anthony Krutzkamp as newly created position of Manager of KCB II. Carney also announced eleven new members of the Company, increasing the Company from 28 to 29 members for the 2014-2015 season. He also announced the appointment of four new KCB II dancers, which stands at six members. Carney also announced the creation of a Trainee Program with five students, two selected from Kansas City Ballet School. High resolution photos can be downloaded here. Carney stated, “With the support of the community, we were able to develop and grow the Company as well as expand the scope of our training programs. We are pleased to welcome these exceptional dancers to Kansas City Ballet and Kansas City. I know our audiences will enjoy the talent and diversity that these artists will add to our existing roster of highly professional world class performers that grace our stage throughout the season ahead. -

And Then There Were Two Jan01

Website of the Telegraph Media Group with breaking news, sport, business, latest UK and world news. Content from the Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph newspapers and video from Telegraph TV. And then there were two In 1998, six of the Royal Ballet's male stars left to form the pioneering K Ballet. Two of them - Michael Nunn and William Trevitt - tell Ismene Brown how their optimism turned sour By Ismene Brown 12:00AM GMT 23 Jan 2001 'ROYAL Ballet reels as top dancers break away," said the headline in The Daily Telegraph. Ballet dancers rarely make the news pages, but, at the end of 1998, there was something strangely potent about the idea of six leading men at our national flagship company leaving to set up their own company. They called themselves K Ballet, after their leader, the Royal Ballet's virtuoso Tetsuya Kumakawa, whose fame in Japan had created the opening. Ballet boys: Michael Nunn [left] and William Trevitt, who were eclipsed by the star status of fellow K Ballet member Tetsuya Kumakawa It was the lowest point in the Royal Ballet's annus horribilis, with the Opera House shut for development, the dancers under threat of mass redundancy, chief executives entering and exiting, and the new Sadler's Wells Theatre, where the company was dancing in exile, not finished. Royal Ballet director Anthony Dowell reacted to the resignations as to a severe personal slight. But storms pass, and somehow ballet life goes on. The Royal Ballet survived its painful loss by using its reputation to attract visiting guests, while older resident males found themselves unexpectedly appreciated again. -

St Mary's University Announce New Partnership with the Royal Ballet To

St Mary’s University announce new partnership with The Royal Ballet to deliver strength and conditioning and sports science support The School of Sport, Health and Applied Science (SHAS) at St Mary’s University, Twickenham and the Royal Opera House are delighted to announce an exciting new partnership to deliver sports science support services to the highly prestigious and world-renowned Royal Ballet based in London’s Covent Garden. The partnership will see St Mary’s academics providing strength and conditioning and sports science support to the world-class ballet dancers, working closely with The Royal Ballet’s Clinical Director Greg Retter. They will also design bespoke programmes to enhance dance performance and recovery after injury. In addition, the partnership will give opportunity for research into the mechanics behind ballet and professional dance. To facilitate the research St Mary’s is offering a fully funded position on its new Masters by Research degree, giving the St Mary’s student the unique opportunity to work and study in an internationally renowned ballet environment. The student will also improve knowledge and understanding of conditioning for ballet through an innovative programme of research. Head of SHAS Prof John Brewer said, “It is an honour and privilege to have been awarded this contract, and it is testimony to the reputation and expertise of our sports science and strength and conditioning staff at St Mary’s. We are looking forward to working closely with the Royal Ballet and the dancers over the coming years, and I am certain that we can contribute to the marginal gains that are critical for improving and sustaining their performance.” Greg Retter said “The health of our dancers is of the utmost importance to us at The Royal Ballet and the prevention of injury and the highest quality rehabilitation is constantly at the forefront of our thinking. -

Worldballetday 2021 Join the World's Top Ballet Companies for Biggest

Press Release 1 September 2021 #WorldBalletDay 2021 Join the world’s top ballet companies for biggest-ever global celebration of dance • Free digital live stream on 19 October • #WorldBalletDay collaborates with TikTok for the first time • Watch via www.worldballetday.com Today, The Royal Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet and The Australian Ballet are delighted to announce that #WorldBalletDay 2021 will take place on 19 October. The global celebration returns for its eighth year, bringing together a host of the world’s leading companies for a packed day of dance. Over the course of the day, rehearsals, discussions and classes will be streamed for free across 6 continents, offering unique behind-the-scenes glimpses of ballet’s biggest stars and upcoming performers. With COVID-19 guidelines changing daily across the globe, dance companies have struggled to return to stages and rehearsal studios. This year's celebration will recognise the extraordinary resilience of this art form in the face of those challenges, showcasing the breadth of talent performing, choreographing, and working on productions today. The 2021 edition of #WorldBalletDay is set to be the biggest ever. In collaboration with TikTok, and with streams across YouTube and Facebook, this year’s viewership is expected to exceed the previous record set in 2019, when #WorldBalletDay content was viewed over 300 million times. Kevin O’Hare, Director of The Royal Ballet, comments: ‘This year’s celebration of our cherished art form will be more important and meaningful than ever, as friends and colleagues around the world return to the stage and the studio, many still with great difficulty. -

Northern Ballet's Dracula to Be Aired on BBC Four on Sunday 31 May At

Thursday 21 May 2020 For immediate release Northern Ballet’s Dracula to be aired on BBC Four on Sunday 31 May at 10pm David Nixon OBE’s Dracula will be shown on BBC Four on Sunday 31 May and BBC iPlayer throughout June as part of their popular Pay As You Feel Digital Season. After sell-out live performances and an international livestream last October, this adaptation of Bram Stoker’s classic will make its television debut at 10pm. northernballet.com/pay-as-you-feel Click here to download images When theatres closed in March Northern Ballet, along with the rest of the theatre industry, was severely impacted and had to cut their spring tour after just one performance. In response, the Company pledged to keep bringing world-class ballet to their audiences through a new Pay As You Feel Digital Season. To date the season has been watched by over 200,000 people and attracted donations of over £20,000. The Company is set to face a loss of over £1M in box office income due to COVID-19 which may impact their ability to pay their workforce, many of whom are freelancers, as well as their ability to present new ballets. Whilst theatres remain dark, the Company aims to continue making their performances available online and on TV, encouraging audiences to donate when they watch, if they are able. Those who wish to support the Company can donate at northernballet.com/pay-as-you-feel Dracula was recorded at Leeds Playhouse on Halloween 2019 and streamed live to over 10,000 viewers in cinemas across Europe. -

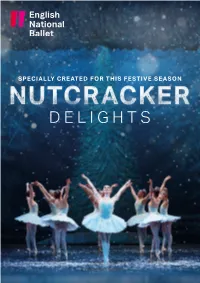

Nutcracker Delights

SPECIALLY CREATED FOR THIS FESTIVE SEASON DELIGHTS I A word from Tamara Rojo Welcome to Nutcracker Delights. I am And, finally, thank you to each of you joining us delighted that we are back on stage at the here for this festive celebration. We are so very This programme was designed for English London Coliseum and that we are once again happy to be able to share this space with you National Ballet’s planned season of Nutcracker able to share our work, live in performance, with again. I hope that you enjoy the performance. President Delights at the London Coliseum from you all. 17 December 2020 — 3 January 2021. Dame Beryl Grey DBE The extraordinary circumstances of 2020 have Chair As London moved into Tier 4 COVID-19 changed the way all of us work and live, and restrictions with the subsequent cancellation Sir Roger Carr I believe more strongly than ever in the power of all scheduled performances of Nutcracker Artistic Director of the arts to provide inspiration, shared Delights, the Company decided to film and Tamara Rojo CBE experience, hope, and solace. Tamara Rojo CBE share online, for free, a recording of this Artistic Director What a pleasure to mark our return to live specially adapted production as a gift to our Executive Director English National Ballet performance by continuing a Christmas fans at the close of our 70th Anniversary year. Patrick Harrison tradition we have held dear for 70 years. We have performed a version of Nutcracker Chief Operating Officer After a year that has been so difficult for so every year since the Company was founded, Grace Chan many, I am thrilled that we are able to bring and were determined to continue this much- Music Director some festive magic back to the stage. -

David Hallberg Returns to the Royal Ballet As Principal Guest Artist for the 2019/20 Season

October 2019 David Hallberg returns to The Royal Ballet as Principal Guest Artist for the 2019/20 Season David Hallberg becomes a Principal Guest Artist of The Royal Ballet in the 2019/20 Season. Hallberg has a long association partnering Royal Ballet Principal dancer Natalia Osipova and during the 2018/19 Season they performed together at the Royal Opera House in Frederick Ashton ’s A Month in the Country and Kenneth MacMillan ’s Romeo and Juliet. The pair also performed the famous balcony pas de deux from Romeo and Juliet at the centenary celebration for Margot Fonteyn in June 2019. Hallberg continues his partnership with Osipova this Season, beginning with Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon on 15 and 19 October. On 20 November he makes his debut as Prince Florimund in The Royal Ballet’s production of The Sleeping Beauty with Osipova as Princess Aurora. He will also make his debut in the first revival of the Company’s new production of Swan Lake on 11 March. Kevin O’Hare, Director of The Royal Ballet comments ‘It’s a great pleasure to welcome David Hallberg back to the Company for this Season. His partnership with Natalia Osipova is thrilling to watch and together they have a very special chemistry. David is a much-loved principal of American Ballet Theater and it is wonderful for audiences this side of the Atlantic to have the opportunity to see him dance with The Royal Ballet across a variety of our signature repertory.’ David Hallberg adds ‘It’s such an honour to join The Royal Ballet as Principal Guest Artist and dance beside, not only a -

Alessandra Ferri Returns to the Royal Opera House with TRIO

December 2018 Alessandra Ferri returns to the Royal Opera House with TRIO ConcertDance, the first dance performance to be staged in the newly refurbished Linbury Theatre Thursday 17 – Sunday 27 January 2019 #ROHtrio Alessandra Ferri and Herman Cornejo. Photographed by Lucas Chilczulk World renowned ballerina Alessandra Ferri returns to the Royal Opera House with the UK premiere of TRIO ConcertDance, the first dance performance to be staged in the newly refurbished Linbury Theatre, the West End’s newest and most intimate theatre. TRIO ConcertDance is a joint collaboration between Alessandra Ferri, American Ballet Theatre Principal Herman Cornejo and acclaimed concert pianist Bruce Levingston. The three artists have come together to create an evening of classic and contemporary piano solos and innovative choreography featuring work by Herman Cornejo, Russell Maliphant, Angelin Preljocaj, Fang-Yi Sheu, Demis Volpi and Wayne For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press- and-media McGregor. The programme celebrates the intimate and inextricable connection between music and dance, exploring the common ground between these two art-forms. Alessandra Ferri will dance with Herman Cornejo, with Bruce Levingston accompanying the performances and playing a number of solos on stage. Music featured includes pieces by J.S Bach, Fryderyk Chopin, Nils Frahm, Philip Glass, GyÔrgy Ligeti, W.A Mozart, Erik Satie and Domenico Scarlatti. Alessandra Ferri is a former Principal dancer with The Royal Ballet. She returned as a Guest Artist in 2015 to dance in Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works for which she won an Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance.