Bivergent Thrust Wedges Surrounding Oceanic Island Arcs: Insight from Observations and Sandbox Models of the Northeastern Caribbean Plate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Megathrust Earthquakes to Brittle Deformation in a Fossil Accretionary Complex

ARTICLE Received 9 Dec 2014 | Accepted 13 May 2015 | Published 24 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 OPEN Linking megathrust earthquakes to brittle deformation in a fossil accretionary complex Armin Dielforder1, Hauke Vollstaedt1,2, Torsten Vennemann3, Alfons Berger1 & Marco Herwegh1 Seismological data from recent subduction earthquakes suggest that megathrust earthquakes induce transient stress changes in the upper plate that shift accretionary wedges into an unstable state. These stress changes have, however, never been linked to geological structures preserved in fossil accretionary complexes. The importance of coseismically induced wedge failure has therefore remained largely elusive. Here we show that brittle faulting and vein formation in the palaeo-accretionary complex of the European Alps record stress changes generated by subduction-related earthquakes. Early veins formed at shallow levels by bedding-parallel shear during coseismic compression of the outer wedge. In contrast, subsequent vein formation occurred by normal faulting and extensional fracturing at deeper levels in response to coseismic extension of the inner wedge. Our study demonstrates how mineral veins can be used to reveal the dynamics of outer and inner wedges, which respond in opposite ways to megathrust earthquakes by compressional and extensional faulting, respectively. 1 Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1 þ 3, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 2 Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 3 Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Geˆopolis 4634, Lausanne CH-1015, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:7504 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts, Bahrain GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts

GEO 2008 conference abstracts, Bahrain GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts he abstracts of the GEO 2008 Conference presentations (3-5 March 2008, Bahrain) are published in Talphabetical order based on the last name of the first author. Only those abstracts that were accepted by the GEO 2008 Program Committee are published here, and were subsequently edited by GeoArabia Editors and proof-read by the corresponding author. Several names of companies and institutions to which presenters are affiliated have been abbreviated (see page 262). For convenience, all subsidiary companies are listed as the parent company. (#117804) Sandstone-body geometry, facies existing data sets and improve exploration decision architecture and depositional model of making. The results of a recent 3-D seismic reprocessing Ordovician Barik Sandstone, Oman effort over approximately 1,800 square km of data from the Mediterranean Sea has brought renewed interest in Iftikhar A. Abbasi (Sultan Qaboos University, Oman) deep, pre-Messinian structures. Historically, the reservoir and Abdulrahman Al-Harthy (Sultan Qaboos targets in the southern Mediterranean Sea have been the University, Oman <[email protected]>) Pliocene-Pleistocene and Messinian/Pre-Messinian gas sands. These are readily identifiable as anomalousbright The Lower Paleozoic siliciclastics sediments of the amplitudes on the seismic data. The key to enhancing the Haima Supergroup in the Al-Haushi-Huqf area of cen- deeper structure is multiple and noise attenuation. The tral Oman are subdivided into a number of formations Miocene and older targets are overlain by a Messinian- and members based on lithological characteristics of aged, structurally complex anhydrite layer, the Rosetta various rock sequences. -

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

Caribbean Plate Tilted and Actively Dragged Eastwards by Low-Viscosity Asthenospheric flow ✉ Yi-Wei Chen 1 , Lorenzo Colli1, Dale E

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21723-1 OPEN Caribbean plate tilted and actively dragged eastwards by low-viscosity asthenospheric flow ✉ Yi-Wei Chen 1 , Lorenzo Colli1, Dale E. Bird1,2, Jonny Wu 1 & Hejun Zhu 3 The importance of a low-viscosity asthenosphere underlying mobile plates has been high- lighted since the earliest days of the plate tectonics revolution. However, absolute asthe- nospheric viscosities are still poorly constrained, with estimates spanning up to 3 orders of 1234567890():,; magnitude. Here we follow a new approach using analytic solutions for Poiseuille-Couette channel flow to compute asthenospheric viscosities under the Caribbean. We estimate Caribbean dynamic topography and the associated pressure gradient, which, combined with flow velocities estimated from geologic markers and tomographic structure, yield our best- estimate asthenospheric viscosity of (3.0 ± 1.5)*1018 Pa s. This value is consistent with independent estimates for non-cratonic and oceanic regions, and challenges the hypothesis that higher-viscosity asthenosphere inferred from postglacial rebound is globally- representative. The active flow driven by Galapagos plume overpressure shown here con- tradicts the traditional view that the asthenosphere is only a passive lubricating layer for Earth’s tectonic plates. 1 Department of Earth and Atmospheric Science, University of Houston, Houston, USA. 2 Bird Geophysical, Houston, USA. 3 Department of Geosciences, ✉ University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, USA. email: [email protected] NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2021) 12:1603 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21723-1 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21723-1 he concept of a weak asthenosphere sandwiched between Eastward asthenospheric flow under the Caribbean (Fig. -

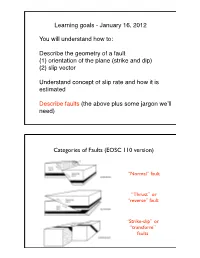

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

1. Introduction1

Kimura, G., Silver, E.A., Blum, P., et al., 1997 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 170 1. INTRODUCTION1 Shipboard Scientific Party2 The planet is profoundly affected by the distributions and rates of al., 1990), which extends from the Caribbean coast of Colombia to materials that enter subduction zones. The material that is accreted to Limon, Costa Rica. In Costa Rica, the boundary consists of a diffuse the upper plate results in growth of the continental mass, and fluids left lateral shear zone from Limon to the Middle America Trench squeezed out of this accreted mass have significance for biologic and (Ponce and Case, 1987; Jacob and Pacheco, 1991; Guendel and geochemical processes occurring on the margins. Material that is not Pacheco, 1992; Goes et al., 1993; Fan et al., 1993; Marshall et al., accreted or underplated to the margin bypasses surface residency and 1993; Fisher et al., 1994; Protti and Schwartz, 1994). The north- descends into the mantle, chemically affecting both the mantle and trending boundary between the Cocos and Nazca Plates is the right- magmas generated therefrom. Subduction of the igneous ocean crust lateral Panama fracture zone. West of this fracture zone is the Cocos returns rocks to the mantle that earlier had been fractionated from it Ridge, a trace of the Galapagos Hotspot, which subducts beneath the in spreading centers, along with products of chemical alteration that Costa Rican segment of the Panama Block. occur on the seafloor. Sediments that are subducted include biogenic, The Nicoya Peninsula is composed of Late Jurassic to Late Creta- volcanogenic, authigenic, and terrigenous debris. -

Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-06-11 Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott Royal Greenhalgh Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Greenhalgh, Scott Royal, "Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4095. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science John H. McBride, Chair Brooks B. Britt Bart J. Kowallis John M. Bartley Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Scott R. Greenhalgh All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science The kinematic evolution and along-strike variation in contractional deformation in over- thrust belts are poorly understood, especially in three dimensions. The Sevier-age Cordilleran overthrust belt of southwestern Wyoming, with its abundance of subsurface data, provides an ideal laboratory to study how this deformation varies along the strike of the belt. We have per- formed a detailed structural interpretation of dual vergent thrusts based on a 3D seismic survey along the Wyoming salient of the Cordilleran overthrust belt (Big Piney-LaBarge field). -

THE GROWTH of SHEEP MOUNTAIN ANTICLINE: COMPARISON of FIELD DATA and NUMERICAL MODELS Nicolas Bellahsen and Patricia E

THE GROWTH OF SHEEP MOUNTAIN ANTICLINE: COMPARISON OF FIELD DATA AND NUMERICAL MODELS Nicolas Bellahsen and Patricia E. Fiore Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 e-mail: [email protected] be explained by this deformed basement cover interface Abstract and does not require that the underlying fault to be listric. In his kinematic model of a basement involved We study the vertical, compression parallel joint compressive structure, Narr (1994) assumes that the set that formed at Sheep Mountain Anticline during the basement can undergo significant deformations. Casas early Laramide orogeny, prior to the associated folding et al. (2003), in their analysis of field data, show that a event. Field data indicate that this joint set has a basement thrust sheet can undergo a significant heterogeneous distribution over the fold. It is much less penetrative deformation, as it passes over a flat-ramp numerous in the forelimb than in the hinge and geometry (fault-bend fold). Bump (2003) also discussed backlimb, and in fact is absent in many of the forelimb how, in several cases, the basement rocks must be field measurement sites. Using 3D elastic numerical deformed by the fault-propagation fold process. models, we show that early slip along an underlying It is noteworthy that basement deformation often is thrust fault would have locally perturbed the neglected in kinematic (Erslev, 1991; McConnell, surrounding stress field, inducing a compression that 1994), analogue (Sanford, 1959; Friedman et al., 1980), would inhibit joint formation above the fault tip. and numerical models. This can be attributed partially Relating the absence of joints in the forelimb to this to the fact that an understanding of how internal stress perturbation, we are able to constrain the deformation is delocalized in the basement is lacking. -

Contractional Tectonics: Investigations of Ongoing Construction of The

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Contractional Tectonics: Investigations of Ongoing Construction of the Himalaya Fold-thrust Belt and the Trishear Model of Fault-propagation Folding Hongjiao Yu Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Yu, Hongjiao, "Contractional Tectonics: Investigations of Ongoing Construction of the Himalaya Fold-thrust Belt and the Trishear Model of Fault-propagation Folding" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2683. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2683 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CONTRACTIONAL TECTONICS: INVESTIGATIONS OF ONGOING CONSTRUCTION OF THE HIMALAYAN FOLD-THRUST BELT AND THE TRISHEAR MODEL OF FAULT-PROPAGATION FOLDING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geology and Geophysics by Hongjiao Yu B.S., China University of Petroleum, 2006 M.S., Peking University, 2009 August 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have had a wonderful five-year adventure in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at Louisiana State University. I owe a lot of gratitude to many people and I would not have been able to complete my PhD research without the support and help from them. -

Deepwater Fold-And-Thrust Belt Along New Caledonia's Western Margin

Deepwater fold-and-thrust belt along New Caledonia’s western margin: relation to post-obduction vertical motions J. Collot, M. Patriat, S. Etienne, P. Rouillard, F. Soetaert, C Juan, B. Marcaillou, Giulia Palazzin, Camille Clerc, P. Maurizot, et al. To cite this version: J. Collot, M. Patriat, S. Etienne, P. Rouillard, F. Soetaert, et al.. Deepwater fold-and-thrust belt along New Caledonia’s western margin: relation to post-obduction vertical motions. Tectonics, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2017, 36, pp.2108-2122. 10.1002/2017TC004542. insu-01614136 HAL Id: insu-01614136 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-01614136 Submitted on 24 Oct 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PUBLICATIONS Tectonics RESEARCH ARTICLE Deepwater Fold-and-Thrust Belt Along New 10.1002/2017TC004542 Caledonia’s Western Margin: Relation Key Points: to Post-obduction Vertical Motions • New deepwater fold-and-thrust belt discovered off New Caledonia’s J. Collot1 , M. Patriat1,2 , S. Etienne1,3 , P. Rouillard1,3,4, F. Soetaert1,2, C. Juan1, western margin 5 6 7 1 1,3 1,3 1 • Origin of the deepwater B. Marcaillou , G. Palazzin , C. -

Collision Orogeny

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 PROCESSES OF COLLISION OROGENY Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Shortening of continental lithosphere: the neotectonics of Eastern Anatolia a young collision zone J.F. Dewey, M.R. Hempton, W.S.F. Kidd, F. Saroglu & A.M.C. ~eng6r SUMMARY: We use the tectonics of Eastern Anatolia to exemplify many of the different aspects of collision tectonics, namely the formation of plateaux, thrust belts, foreland flexures, widespread foreland/hinterland deformation zones and orogenic collapse/distension zones. Eastern Anatolia is a 2 km high plateau bounded to the S by the southward-verging Bitlis Thrust Zone and to the N by the Pontide/Minor Caucasus Zone. It has developed as the surface expression of a zone of progressively thickening crust beginning about 12 Ma in the medial Miocene and has resulted from the squeezing and shortening of Eastern Anatolia between the Arabian and European Plates following the Serravallian demise of the last oceanic or quasi- oceanic tract between Arabia and Eurasia. Thickening of the crust to about 52 km has been accompanied by major strike-slip faulting on the rightqateral N Anatolian Transform Fault (NATF) and the left-lateral E Anatolian Transform Fault (EATF) which approximately bound an Anatolian Wedge that is being driven westwards to override the oceanic lithosphere of the Mediterranean along subduction zones from Cephalonia to Crete, and Rhodes to Cyprus. This neotectonic regime began about 12 Ma in Late Serravallian times with uplift from wide- spread littoral/neritic marine conditions to open seasonal wooded savanna with coiluvial, fluvial and limnic environments, and the deposition of the thick Tortonian Kythrean Flysch in the Eastern Mediterranean.