The Ohio (Great East Baldwyn Or Manx)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

Sources for Family History RESEARCHING Manx Genealogy

lIBRARy & ARCHIvE SERvICE SoURCES FoR FAMIly HISToRy RESEARCHING MANx GENEAloGy Researching your family history can be an exciting hobby and most of the sources for the study of Manx genealogy are available in the Manx Museum Reading Room. Many of these are held on microfilm or microfiche. Please note that there is no need to book a reading machine in advance. If you need assistance the staff will be only too happy to help. This information sheet outlines some of the available sources held in Manx National Heritage’s library & Archive collections, the Isle of Man Government’s Civil Registry and Public Record office. Family History Internment “Unlocking The Past: a guide to exploring family and local We provide a separate collection guide of sources of history in the Isle of Man” by Matthew Richardson. information for people interned on the Isle of Man during Manx National Heritage, 2011 (Library Ref: G.90/RIC). the First and Second World Wars. This is an invaluable guide on how to use the enormous variety of records that exist for the Isle of Man in the National Civil Registration of Births, Marriages and Library & Archive collections, including the growing number that are accessible online through the Museum – Deaths and Adoption www.imuseum.im Records of the compulsory registration of births and deaths began in 1878 and for marriages in 1884. Certificates can be A shorter introduction to family history is “The Manx Family obtained, for a fee, from the Civil Registry: Civil Registry, Tree: a guide to records in the Isle of Man” 3rd edition, Deemsters Walk, Buck’s Road, Douglas, IM1 3AR by Janet Narasimham (edited by Nigel Crowe and Priscilla Tel: (01624) 687039 Lewthwaite). -

Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. an Examination of Manx Farming Between 1750 and 1900

115 Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. An examination of Manx farming between 1750 and 1900 CJ Page Introduction Set in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man was far from being an isolated community. Being over 33 miles long by 13 miles wide, with a central mountainous land mass, meant that most of the cultivated area was not that far from the shore and the influence of the sea. Until recent years the Irish Sea was an extremely busy stretch of water, and the island greatly benefited from the trade passing through it. Manxmen had long been involved with the sea and were found around the world as members of the British merchant fleet and also in the British navy. Such people as Fletcher Christian from HMAV Bounty, (even its captain, Lieutenant Bligh was married in Onchan, near Douglas), and also John Quilliam who was First Lieutenant on Nelson's Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, are some of the more notable examples. However, it was fishing that employed many Manxmen, and most of these fishermen were also farmers, dividing their time between the two occupations (Kinvig 1975, 144). Fishing generally proved very lucrative, especially when it was combined with the other aspect of the sea - smuggling. Smuggling involved both the larger merchant ships and also the smaller fishing vessels, including the inshore craft. Such was the extent of this activity that by the mid- I 8th century it was costing the British and Irish Governments £350,000 in lost revenue, plus a further loss to the Irish administration of £200,000 (Moore 1900, 438). -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

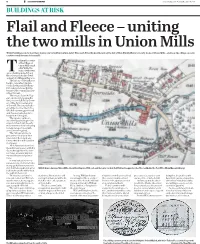

Flail and Fleece

14 ISLE OF MAN EXAMINER www.iomtoday.co.im Tuesday, December 17, 2019 BUILDINGS AT RISK Flail and Fleece – uniting the two mills in Union Mills Whilst buildings can be lost, their legacy can be hidden in plain sight! This week Priscilla Lewthwaite of the Isle of Man Family History Society looks at Union Mills – and how the village owes its existence and its name to two mills. oday in the centre of the village of Union Mills stand a few walls, the ruins of what was once a thriving industry and Tthe sole reason for the devel- opment of a village in this area. The history of the mill goes back to our earliest land re- cords, the Manorial Roll 1511- 1515, where it states that the tenant of the corn mill paid 9s 8d Lord’s Rent. The tenant, Oates McTag- gart, in return for paying his rent, received all the landown- ers of the district as tenants of the mill. The tenants had to grind their corn at the mill to which they were apportioned and they were also bound to keep the mill in repair. The repairs could con- sist of being asked to provide straw for thatch (all the early mills were thatched) or having to help transport new mill- stones when required. The mill owners lived a precarious life and ran into financial difficulties many times when the mill had to be mortgaged. John Stevenson inherited the mill, then known as Mullin Oates through his wife, Aver- ick Oates, whose family had owned it for several genera- tions. -

Culture Which Is As Evident Today As It Was 1,000’S of Years Ago

C U LT U R E The Isle of Man has a unique and varied culture which is as evident today as it was 1,000’s of years ago. Uncover the amazing history and heritage of the Island by following the ‘Story of Mann’ trail, whilst taking in some of the Island’s unique arts, folklore and cuisine along the way. THE STORY OF MANN Manx National Heritage reveals 10,000 years of Isle of Man history through the award-winning Story of Mann - a themed trail of presentations and attractions which takes you all over the Island. Start off by visiting the award-winning Manx Museum in Douglas for an overview and introduction to the trail before choosing your preferred destinations. Attractions on the trail include: Castle Rushen, Castletown. One of Europe’s best-preserved medieval castles, dating from the 12th Century. Detailed displays authentically recreate castle life as it was for the Kings and Lords of Mann. Cregneash Folk Village, near Port St Mary. Life as it was for 19th century crofters is authentically reproduced in this living museum of thatched whitewashed cottages and working farm. Great Laxey Wheel and Mines Trail, Laxey. The ‘Lady Isabella’ water wheel is the largest water wheel still operating in the world today. Built in 1854 to pump water from the mines, it is an important part of the Island’s once-thriving mining heritage. The old mines railway has now been restored. House of Mannanan, Peel. An interactive, state of the art heritage centre showing how the early Manx Celts and Viking settlers shaped the Island’s history. -

Manx National Heritage Sites Information

Historic Buildings Architect/Surveyor Thornbank, Douglas: Architects rendering for restoration of Baillie-Scott House owned by MNH (Horncastle:Thomas) Information for Applicants Manx National Heritage Historic Buildings Architect/Surveyor Our Organisation Manx National Heritage (MNH) is the trading name given to the Manx Museum and National Trust. The Trust was constituted in 1886 with the purpose of creating a national museum of Manx heritage and culture and has grown steadily in scope and reach and it is now the Islands statutory heritage agency. MNH exists to take a lead in protecting, conserving, making accessible and celebrating the Island’s natural and cultural heritage for current and future generations whilst contributing to the Island’s prosperity and quality of life MNH is a small organisation sponsored but operating at arm’s length from the Isle of Man Government. Our small properties management team is responsible for thirteen principle sites of historic and landscape significance, an array of field monuments and around 3000 acres of land. MNH welcomes around 400,000 visits to its properties every year and is also home to the National Museum, the National Archives and the National Art Gallery. Our Vision, principles and values MNH’s vision is “Securing the Future of Our Past”. Underpinning this vision are key principles and values which guide everyone who works for the organisation as they conduct their core business and their decision-making. Being led by and responsive to our visitors and users Working in collaboration -

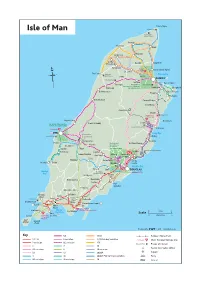

Isle of Man Bus Map.Ai

Point of Ayre Isle of Man Lighthouse Point of Ayre Visitor Centre Smeale The Lhen Bride Andreas Jurby East Jurby Regaby Dog Mills Threshold Sandygate Grove Grand Island Hotel St. Judes Museum The Cronk Ballaugh Ramsey Bay Old Church Garey Sulby RAMSEY Wildlife Park Lezayre Port e Vullen Curraghs For details of Albert Tower bus services in Ramsey, Ballaugh see separate map Lewaigue Maughold Bishopscourt Dreemskerry Hibernia Ballajora Kirk Michael Corony Bridge Glen Mona SNAEFELL Dhoon Laxey Wheel Dhoon Glen & Mines Trail Knocksharry Ballaragh Laxey For details of bus services Cronk-y-Voddy in Peel, see separate map Laxey Woollen Mills Old Laxey Peel Castle PEEL Laxey Bay Tynwald Mills Corrins Folly Tynwald Hill Ballabeg Ballacraine Baldrine Patrick For details of Halfway House Greeba bus services St. John’s in Douglas, Gordon Hope see separate map Groudle Glen and Railway Glenmaye Crosby Onchan Lower Foxdale Strang Governors Glen Vine Bridge Eairy Foxdale Union Mills Derby Niarbyl Dalby Braddan Castle NSC Douglas Bay Braaid Cooil DOUGLAS Niarbyl Rest Home Bay for Old Horses St. Mark’s Quines Hill Ballamodha Newtown Santon Port Soderick Orrisdale Silverdale Glen Bradda Ballabeg West Colby Level Cross Milners Tower Four Ballasalla Bradda Head Ways Ronaldsway Airport Port Erin Shore Hotel Castle Rushen Cregneash Bay ny The Old Grammar School Carrickey Castletown 03miles Port Scale Sound Cregneash St. Mary 05kilometres Village Folk Museum Calf Spanish of Man Head Produced by 1.9.10 www.fwt.co.uk Key 5/6 17/18 Railway / Horse Tram 1,11,12 6 variation 17/18 Sunday variation Peel Castle Manx National Heritage Site 2 variation 6C variation 17B Tynwald Mills Places of interest 3 7 19 Tourist Information Office 3A variation 8 19 variation X3 13 20/20A Airport 4 16 20/20A Point of Ayre variation Ferry 4A variation 16 variation 29 Seacat. -

The Laxey Valley

UK Tentative List of Potential Sites for World Heritage Nomination: Application form Please save the application to your computer, fill in and email to: [email protected] The application form should be completed using the boxes provided under each question, and, where possible, within the word limit indicated. Please read the Information Sheets before completing the application form. It is also essential to refer to the accompanying Guidance Note for help with each question, and to the relevant paragraphs of UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, (OG) available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines Applicants should provide only the information requested at this stage. Further information may be sought in due course. (1) Name of Proposed World Heritage Site The Laxey Valley (2) Geographical Location Name of country/region United Kingdom – Crown Dependency – Isle of Man Grid reference to centre of site OSGB243210485220 (The Great Laxey Wheel); 54º 14’ 19”N, 4º 24’ 26”W Please enclose a map preferably A4-size, a plan of the site, and 6 photographs, preferably electronically. page 1 (3) Type of Site Please indicate category: Natural Cultural Mixed Cultural Landscape (4) Description Please provide a brief description of the proposed site, including the physical characteristics. 200 words The village of Laxey and the Laxey valley continues to be an area for tourism, transport and industrial heritage which is one of the iconic sites of national identity for the Isle of Man. Laxey was the centre of a lead and zinc-mining industry which was once one of the most important to be worked in Britain, and at the time, in the world. -

Home Deliveries List As at 3Rd April 2020

Manx Utilities Vulnerable needing assistance Emergency Top Up www.manxutilities.im 687675 During Office Hours All Island Out of Hours emergency assistance 687687 Manx Gas www.manxgas.com Vulnerable Customers contact 644444 Main Supermarkets offer selected Times Shoprite Little Switzerland, Bridson Street, Port Erin Overs 70's between 8.00am & 9.00am Bowring Road, Ramsey, Derby Road, Peel, Tuesday, Thursday & Saturday Village Walk, Onchan Co-Op All Co-op's around Island Daily for older and Vulnerable persons between 9.00am & 10.00am Ramsey Co-Op can offer the following if somebody does the shopping, pays for it they can deliver it to places in the North and to laxey. Need to check delivery times before you shop Tesco Douglas Monday, Wednesday, Friday For older and Vulnerable persons between 9.00am & 10.00am Tesco on Line www.tesco.com All Island when you can get a slot Monday to Sunday Marks & Spencer Douglas Mondays & Thursdays between 8.00am & 9.00am EVF Bray Hill Petrol Station evfltd.touchtakeaway.net/menu Douglas & Onchan Only Over 70's and those in Isolation Payment by card only Wessex Garage evfltd.touchtakeaway.net/menu Douglas & Onchan Only Monday to Friday 333762 Delivered by G4S Spar Shops Anagh Coar Stores 624848 Anagh Coar, Farmhill Home Delivery and or Collection Pulrose Stores 673762 Pulrose Home Delivery and or Collection Port Erin 832247 Port Erin / Rushen Area Only Home Delivery and or Collection Ballaugh 897232 Ballaugh & Kirk Michael Minimum of £8.00 phone order in Delivery next day. Please note no deliveries on a Thursday -

Publicindex Latest-19221.Pdf

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF CHARITIES Registered in the Isle of Man under the Charities Registration and Regulation Act 2019 No. Charity Objects Correspondence address Email address Website Date Registered To advance the protection of the environment by encouraging innovation as to methods of safe disposal of plastics and as to 29-31 Athol Street, Douglas, Isle 1269 A LIFE LESS PLASTIC reduction in their use; by raising public awareness of the [email protected] www.alifelessplastic.org 08 Jan 2019 of Man, IM1 1LB environmental impact of plastics; and by doing anything ancillary to or similar to the above. To raise money to provide financial assistance for parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man whose finances determine they are unable to pay costs themselves. The financial assistance given will be to provide full/part payment towards travel and accommodation costs to and from UK hospitals, purchase of items to help with physical/mental wellbeing and care in the home, Belmont, Maine Road, Port Erin, 1114 A LITTLE PIECE OF HOPE headstones, plaques and funeral costs for children and gestational [email protected] 29 Oct 2012 Isle of Man, IM9 6LQ aged to 16 years. For young adults aged 16-21 years who are supported by their parents with no necessary health/life insurance in place, financial assistance will also be looked at under the same rules. To provide a free service to parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man helping with funeral arrangements of deceased children To help physically or mentally handicapped children or young Department of Education, 560 A W CLAGUE DECD persons whose needs are made known to the Isle of Man Hamilton House, Peel Road, 1992 Department of Education Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 5EZ Particularly for the purpose of abandoned and orphaned children of Romania. -

London Manx Society Who Was Given the Honour of Formally Opening the Festival

NEWSLETTER Summer 2016 Editor – Douglas Barr-Hamilton Annual lunch Thirty-six members and guests of the Society assembled for our annual lunch at the traditional venue in Southampton Row on Saturday, 7th May and thoroughly enjoyed our first social gathering of the year. We dined on leek and potato soup, roasted supreme of chicken and lemon crème brulée while catching up on one other's news. Having toasted the Lord of Mann, sung the Manx National Anthem and toasted the guests and the land of our birth, the guest of honour, Edmund Southworth, director of Manx National Heritage brought us up to date with the organisation's work on the Island in an entertaining speech and kindly answered a number of topical questions. Other guests present were Mrs Suzanne Richardson, Mrs Josie Thacker, Peter Nash and Rev. Justin White. Members who attended were Anne and Nick Alexander, Voirry and Robin Carr, Bryan and Sheila Corrin, Pam and Mike Fiddik, Colin and Sheila Gill, Sally and Peter Miller, Melodie and Harry Waddingham, Sam and Mary Weller, Jim and Sue Wood, Douglas Barr-Hamilton, Margaret Brady, Stewart Christian, Derek Costain, Rose Fowler, Maron Honeyborne, Alastair Kneale, Carol Radcliffe, Margaret Robertson, Maisie Sell, Elizabeth Watson and Mary West. 2 The outgoing president, Alastair Kneale, after three years in the post, handed over to his successor Bryan Corrin from Beckenham. Bryan is Emeritus Professor of Respiratory Medicine at Imperial College, London and a long-time member of the Society. He is a descendant of Richard Corrin of Castletown and Catherine Creer of St Anne’s (presumably Santon) who were married at Braddan in 1839, immediately prior to leaving the island to settle in Liverpool.