“Eating Fresh” in America: Subway Restaurant's Nutritional Rhetoric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tool for Automated Knowledge Base Construction

KELVIN: a tool for automated knowledge base construction Paul McNamee, James Mayfield Tim Finin, Tim Oates Johns Hopkins University University of Maryland Human Language Technology Center of Excellence Baltimore County Dawn Lawrie Tan Xu, Douglas W. Oard Loyola University Maryland University of Maryland College Park Abstract X:Person has-job-title title • X:Organization headquartered-in Y:Location We present KELVIN, an automated system for • processing a large text corpus and distilling a Multiple layers of NLP software are required for knowledge base about persons, organizations, this undertaking, including at the least: detection of and locations. We have tested the KELVIN named-entities, intra-document co-reference resolu- system on several corpora, including: (a) the tion, relation extraction, and entity disambiguation. TAC KBP 2012 Cold Start corpus which con- To help prevent a bias towards learning about sists of public Web pages from the University of Pennsylvania, and (b) a subset of 26k news prominent entities at the expense of generality, articles taken from English Gigaword 5th edi- KELVIN refrains from mining facts from sources tion. such as documents obtained through Web search, 2 3 Our NAACL HLT 2013 demonstration per- Wikipedia , or DBpedia. Only facts that are as- mits a user to interact with a set of search- serted in and gleaned from the source documents are able HTML pages, which are automatically posited. generated from the knowledge base. Each Other systems that create large-scale knowledge page contains information analogous to the bases from general text include the Never-Ending semi-structured details about an entity that are Language Learning (NELL) system at Carnegie present in Wikipedia Infoboxes, along with Mellon University (Carlson et al., 2010), and the hyperlink citations to supporting text. -

Child Pornography Is Sex Trafficking

Child Pornography is Sex Trafficking January 31, 2017 By Human Trafficking Collaborative Network (HTCN) 1 On December 30, 2011, Former President Obama declared January to be National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month. The general public’s awareness of human trafficking has improved considerably over the past years. At the time of this writing, the last day of the 2017 Human Trafficking Awareness Month, we are grateful that many community activities have been held in St. Louis and surrounding areas. Some activists participated in a series of anti- human trafficking campaigns at the Missouri Capital; some held a vigil for survivors and victims who lost their lives; some held resource dissemination events to better inform service providers, concerned citizens and students. In light of a very recent high-profile indictment of a St. Louis County child pornography case, we are compelled to providing regional information on child pornography in the context of human trafficking. As defined by the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TPVA, 2000), [i] human trafficking includes recruitment, harboring, provision, receipt, transportation and/or obtaining of individuals by using force or threats, coercion, fraud and/or using systems of indebtedness or debt bondage for purposes of sexual or other forms of economic exploitation. Coercion includes threats of physical or psychological harm to the 1. The Human Trafficking Collaborative Network (HTCN) core members include: Rumi Kato Price (WU School of Medicine); Andrea Nichols (WU Brown School of Social Work & Women Gender and Sexuality Studies; St. Louis Community College Forest Park); Kathleen Thimsen (Goldfarb School of Nursing at BJC); Tonya Edmond (WU Brown School of Social Work); Richelle Clark & Matthew Brown (IPH Center for Community Health Partnership & Research; Sundari Balan (WU School of Medicine); Natalie Palmer (Goldfarb School of Nursing at BJC); and Porpong (Paul) Boonmak (McDonnell International Scholars Academy, Master of Population Health Sciences; WU School of Medicine). -

Subway Officially Cuts Ties with Jared

adage.com http://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/subway-officially-cuts-ties-jared/300012/ Subway Officially Cuts Ties With Jared Maureen August 18, Morrison 2015 Subway has appeared to officially sever its ties to longtime spokesman Jared Fogle after news reports surfaced that he was going to plead guilty to possession of child pornography charges on Wednesday. Said the company on Twitter: Earlier on Tuesday, a local Fox affiliate reported that, according to sources, Mr. Fogle was going accept a plea deal on Wednesday, but not much more detail was available. Mr. Fogle initially had his relationship suspended by Subway in early July after federal authorities raided his home. At the time, the federal agents did not specify why they investigated Mr. Fogle's residence, but it came less than two months after Russell Taylor, executive director of the Fogle Foundation, a group that is dedicated to helping teach kids healthy lifestyle habits, was arrested on child pornography charges. Following those charges, Subway and Mr. Fogle said they had severed all ties with Mr. Taylor. ADVERTISING After the federal raid, Subway distanced itself by saying that it had "suspended" its relationship with Jared, but that language left some wiggle room for the brand to reinstate it. The company also removed its Jared references from its website, including what became an unfortunately named game on its kids' site called Jared's Pants Dance. Whether any of this will affect Subway's business of course remains to be seen, but it's possible it won't impact it much. "I don't think it will materially impact Subway -- they already distanced themselves from him," said marketing consultant Denise Lee Yohn in an email. -

How Did Ex-Subway Spokesman Jared Fogle Gain 30 Pounds in Prison? - the Boston Globe

How did ex-Subway spokesman Jared Fogle gain 30 pounds in prison? - The Boston Globe Help Your Favorite Area Non-Profit With GRANT How do people gain weight in prison? E-MAIL FACEBOOK TWITTER GOOGLE+ LINKEDIN 22 /MICHAEL CONROY/ASSOCIATED PRESS Former Subway pitchman Jared Fogle arrives at the federal courthouse in Indianapolis last fall. By Matt Rocheleau GLOBE STAFF MARCH 03, 2016 https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/03/03/how-did-subway-spokesman-jared-fogle-gain-pounds-prison/BEiiFJ2K6lvVnLbk0mgPVN/story.html[4/14/2016 7:13:51 PM] How did ex-Subway spokesman Jared Fogle gain 30 pounds in prison? - The Boston Globe Former Subway restaurant spokesman Jared Fogle has reportedly gained 30 pounds in just his first three months in prison. Such dramatic weight gain while locked up is not an unprecedented phenomenon, researchers have found. Fogle is serving a sentence of more than 15 years for child pornography possession and having sex with underage prostitutes. Before that, Fogle spent 15 years as the face of Subway, crediting his regular diet of the chain’s sandwiches with helping him to lose 245 pounds. His weight loss relapse was reported this week by InTouch Weekly magazine. But there have been other prominent cases of prisoners gaining weight. Serial killer Gary Lee Sampson was reported in 2014 to have gained about 150 pounds over the course of roughly 11 years behind bars. Singer Chris Brown reportedly gained 35 pounds after about three and a half months in prison. Experts blame several factors, which can work in combination with each other. -

The Underlying Psychophysiology of Pedophilic Disorder and the Implications for Treatment Approaches

National Louis University Digital Commons@NLU Dissertations 8-2019 The Underlying Psychophysiology of Pedophilic Disorder and the Implications for Treatment Approaches Tonise Florexil Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, and the Mental and Social Health Commons Recommended Citation Florexil, Tonise, "The Underlying Psychophysiology of Pedophilic Disorder and the Implications for Treatment Approaches" (2019). Dissertations. 554. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss/554 This Dissertation - Public Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@NLU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@NLU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Underlying Psychophysiology of Pedophilic Disorder and the Implications for Treatment Approaches Tonise Florexil Doctor of Psychology Florida School of Professional Psychology Patricia S. Dixon, Psy.D. Chair Dr. Eric L. Rosen, Ph.D. Member A Clinical Research Project submitted to the Faculty of the Florida School of Professional Psychology at National Louis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology in Clinical Psychology. Tampa, Florida August 2019 The Doctorate Program in Clinical Psychology Florida School of Professional Psychology at National Louis University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________ Clinical Research Project ___________________________ This is to certify that the Clinical Research Project of Tonise Florexil has been approved by the CRP Committee on August 9, 2019 as satisfactory for the CRP requirement for the Doctorate of Psychology degree with a major in Clinical Psychology Examining Committee: ___________________________________________ Committee Chair: Patricia S. -

Indiana State Report on Human Trafficking 1 | P a G E

Indiana State Report on Human Trafficking 1 | P a g e December 1, 2016 Dear Colleagues, Human trafficking, a scourge against humanity, has far reaching impacts nationally, internationally, and in Indiana. I am pleased to provide the first comprehensive report in the State of Indiana on human trafficking. This is a project prepared over the past 18 months by many individuals and organizations who contributed to the work of the Indiana Protection for Abused and Trafficked Humans Task Force (IPATH), the state-wide human trafficking task force, and others who serve victims and who contribute daily, such as members of law enforcement, victim advocates and legislators. In 2009, when I first became co-chair of the task force with the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Indiana, little was known about this horrific crime, its victims, the perpetrators, or the trauma inflicted on those who fall prey to it. Through my service as the Chair of the National Association of Attorneys General Special Committee on Human Trafficking, I further realized the scope of this scourge and its impact on victims nationally and across the globe. Today we know far more than we did then, or even as far back as 2005 when the taskforce was first created. While we have made tremendous progress in policy, legislation, and research, we still have a long way to go. I am proud to present a summary and overview of the work done by many people in our state, from victim service providers to law enforcement, to lawmakers and researchers. This report represents a cumulative picture of those efforts, and outlines, most importantly, a path forward with ideas, recommendations and thoughts for the future. -

Creative Brief

SITUATION ANALYSIS ● Subway is the fast food restaurant with the most locations nationwide. ● #3 in sales in the the fast food restaurant category. ● For the past two years, Subway sales have been dropping at a faster rate than any other top 25 fast food chain. ● In recent years, Subway has lost its positioning as a healthier choice to fast food. ● The recent PR scandal involving Jared Fogle has not only affected Subway’s Brand Image, but also ended a successful 15 year partnership. CATEGORY ● Convenient, Customizable & Conscientious: Consumers are drawn to QSRs that allow them to customize their orders and choose healthier options. ● Bring on the Bold: Today’s consumer, particularly the growing multicultural segment and younger generation, is more adventurous when it comes to eating hot spices and exotic flavors. ● Make it Mobile: Mobile platforms offer solutions for ordering, marketing, loyalty programs and payment - mobile payments rose to $9 Billion in 2015 (US). ● Decisions, Decisions: 200,000+ restaurant locations in the U.S. alone. ● Fast Casual vs. QSR: 8% | 0 THE COMPETITION Main competition includes the following QSRs: ● McDonalds: the perfect burger experience for families since it is cheap, offers children- friendly menu options and many branches include a playing area ● Burger King: the perfect burger experience for busy and picky-eating individuals 18+, because it offers customization through “have it your way” initiative and includes more higher quality ingredients than McDonalds- the burger is grilled. ● Wendy’s: the perfect meal solution for young people 18-25 looking for healthier fast food options, saving money and to get as much value as possible as the burgers “don't cut corners” and the menu offers seasonal salads. -

On “Violence Against Women”

On Violence Against Women Bennett Capers* I. INTRODUCTION We all know the statistics. One in three women has experienced domestic violence.1 Nearly one in five women has been raped.2 Quite simply, it is not safe being a woman. Or a girl for that matter.3 It is definitely not safe being a co-ed on campus.4 Or a woman in prison.5 Or a female gamer in the virtual world of gaming.6 And there is danger on public streets, if the response to a viral video of a woman being catcalled in New York City is anything to go by.7 Even women who have been trained to use physical violence are at risk. I am referring to the Stanley A. August Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School. B.A. Princeton University; J.D. Columbia Law School. E-mail: [email protected]. The genesis for some of the ideas contained in this Essay first originated in remarks given at a panel entitled Sexual Assault and Violence Against Women at the symposium Locking Up Females, Failing to Protect Them, and Punishing Their Families and Children, held at Southwestern Law School. So my first thanks go to my co-panelists from that event for a lively exchange of ideas. My second thanks go to Aya Gruber, the guest editor of this Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law symposium, for inviting me to participate in this symposium and prompting me to think more deeply about those earlier remarks, and to adapt those remarks into this Essay. NATL CTR. -

Antony Yang Page

ANTONY PAGE Florida International University College of Law 11200 S.W. 8th St., Rafael Diaz-Balart Hall, Miami, FL 33199 (317) 640-3067; [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION 1997 STANFORD LAW SCHOOL, J.D. (with Distinction, GPA 3.8), Stanford • Order of the Coif (Top 10%) • Articles Editor, Stanford Law & Policy Review • Research Assistant: Professor J. Barton; Professor J. Halley • Teaching Assistant: Professor J. Gitelstein (Accounting) 1990 BEEDIE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, M.B.A. (GPA 3.8), Vancouver • Concentration: Organizational Development • University Fellowship (awarded for outstanding scholarship) • Project: Organizing for Global Change: Forms and Processes of International Non-Governmental Organizations • Teaching Assistant: Organizational Development, Research Methods 1988 MCGILL UNIVERSITY, B.Comm. (with Great Distinction, GPA 3.7), Montreal • James McGill Award (outstanding academic achievement) • Herbert Siblin Award (outstanding academic achievement, Management) • Dual major: Business, Psychology (graduated top 10% of class) • Teaching Assistant: Statistics, Advanced Statistics EMPLOYMENT 7/18-present FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW, Miami DEAN & PROFESSOR OF LAW • Lead FIU Law’s educational, research, and fundraising activities, with responsibility for the management and allocation of resources, market-rate programs, and philanthropy, as well as compliance with accreditation standards, -

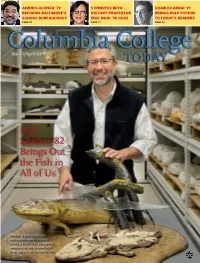

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Off-Campus Student Employment

The SB Weatherman Cometh Page 5 I "Let Each Become Aware" mrr e 1 '/I/ n -+&w.N -V Founded 1957. Incoraorated 1916 Page . Opens BY GUYGRAND'JEAN Erickson from the Art department, Music programs provided the Stute~n~unStaff A new state-of-the art "emedia Dan Weymouth from Music and opportunity to stretch sounds and to SING at the Fine Arts Center Nancy Duffrin of Instructional compose new and original material. opened last Wednesday. Cpmputing, who outlined the In addition to this, musical This is certainly no ordinary various software available. The keyboards could be slid out from SING site as Christa Erickson, a site audience was an beneath the computers. instructor, outlined, allowing arts eyeball camera and projected against The site provided the possibility students hands on experience with, the back wall of the room suggesting to enhance video footage and edit ..Hardware and software the potential of the technology through splicing together images. different than anywhere else." The * After the demonstrations students sinc site represents a, "Collaboration The first of the advanced were left to their own devices to between the LTA consortium of (Art packages was explore the packages with organized Music and Theatre and 'Photo Shop' which allowed the assistant helpers at hand. Instructional Computing," Erickson creation of collages and digital This is a facility which should said. images to be retouched and not be viewed as a regular sinc site. Eager students and faculty software The intention of this site is to, "Raise Sfu/esman/Ru/hChung packed the computer room filled package On show, the computer literacy of arts The SlNC site is in the Fine Arts Center. -

Greenberg Testimony

Testimony of Sally Greenberg Executive Director, National Consumers League on Advertising Trends and Consumer Protection Before the Commerce, Science and Transportation Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, and Insurance United States Senate July 22, 2009 Introduction Good morning, Mr. Chairman, Mr. Ranking Member and members of the subcommittee. My name is Sally Greenberg and I am the Executive Director of the National Consumers League (NCL). 1 I appreciate this opportunity to appear before the subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, and Insurance of the Senate 1 The National Consumers League, founded in 1899, is America's pioneer consumer organization. Our non- profit mission is to protect and promote social and economic justice for consumers and workers in the United States and abroad. For more information, visit www.nclnet.org . Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee to discuss the issue of consumer protections against deceptive advertising. Over its more than one hundred years of existence, NCL has been a fierce critic of misleading advertising, deceptive labeling, and other anti-consumer marketing practices. At the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, NCL volunteers demonstrated to fairgoers that canned green beans touted by food processors as a labor-saving home product were adulterated with green dye. More recently, NCL’s advocacy prompted the FDA in 2001 to investigate misleading claims by tomato juice manufacturers that their products were “fresh.” 2 In 2008, we supported legislation introduced by Senator Bill Nelson of Florida aimed at curbing the use of deceptive advertising practices in the prepaid calling card industry. 3 Earlier this year, in response to an NCL letter to the agency, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned General Mills to stop printing misleading health claims on box of their Cheerios cereal.