On Bended Knee (With Fingers Crossed)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Christianity, Parapsychology, Spiritual Psychiatry, Energy: the Missing Link in Today’S Science

Ernest L. Norman Author, Philosopher, Poet, Scientist, Director-Moderator of Unarius Science of Life. U N A R I U S UNiversal ARticulate Interdimensional Understanding of Science Page ii THE INFINITE CONCEPT of COSMIC CREATION (An Introduction to the Interdimensional Cosmos) HOME STUDY LESSON COURSE (# One course: 1-13 lessons given in 1956) (Advanced Course: 1-7 lessons written in 1960) (Addendum written in 1970) By Ernest L. Norman The Unariun Moderator THE INFINITE CONCEPT OF COSMIC CREATION Norman, Ernest L. The Infinite Concept of Cosmic Creation A Lesson Course on Self Mastery 1. Universal Concept of Energy 2. Cosmology 3. Higher Dimensional Worlds 4. Reincarnation 5. Mental Function 6. Clairvoyance Page iv Other Works by Ernest L. Norman The Pulse of Creation Series: The Voice of Venus Vol.1 The Voice of Eros Vol.2 The Voice of Hermes Vol.3 The Voice of Orion Vol.4 The Voice of Muse Vol.5 Infinite Perspectus Tempus Procedium Tempus Invictus Tempus Interludium I & II Infinite Contact Cosmic Continuum The Elysium (Parables) The Anthenium The Truth About Mars Magnetic Tape Recordings The True Life of Jesus The Story of the Little Red Box (By Unarius' Students & E. L. Norman) Bridge to Heaven - The Revelations of Ruth Norman by Ruth Norman CONTENT THE PATHWAY TO THE STARS PREFACE ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 Lesson 1: General Summation of Entire -

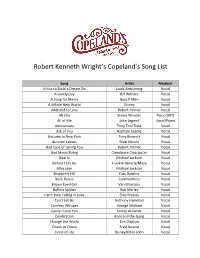

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

'1!.(F WESTWOOD ONE ENTERTAINMENT 9540 Washington Boulevard • Culver City, C.Lifornia 90232-2689 • (310/ 204-5000

J)Y/.\ '1!.(f WESTWOOD ONE ENTERTAINMENT 9540 Washington Boulevard • Culver City, C.lifornia 90232-2689 • (310/ 204-5000 ••• Disc One ••• =:rs=;~1 :~::~.1:33 .·• Open Bbds.: MCI/ 1-800-COLLECT · Track 1 Content: #20. I'll Say Goodbye For Th~ 2 Of Us / Expose' #19. Natural Woman / C. Dion Commercials: :30 Mentholatum CC :30 Visa :30 CBS / Thombirds Outcue: " ... Sunday on CBS." Local Break 1 :30 I Content: #18. I Wilt Remember You / Sarah Mclachlan <tSeg 2 • 16:11 #H. Kiss From A Rose/ Seal .. <Track 2 #16. Grow Old With Me/ Mary Chapin Carpenter Casey's Trivia Quiz Commercials: :30 MCI/ 1-800-COLLECT :30 Luden's :30 U.S. Army :30 CBS / Thornbirds Outcue: " ... Sunday on CBS." Local Break 1 :00 I Content: FMR#1 . Careless Whisper/ Wham! ('.. Seg 3 .:.:. 10:29 ·.·. Track 3 ·· #15. Faithfully/ Peter Cetera Commercials: :30 Alka Seltzer Plus CC :30 Fruit-A-Burst :30 Secret -Trojan Condom PSA Outcue: " ... Trojan brand condoms." Local Break 1 :30 I Content: #14. Don't Cry/ Seal >. Seg 4 :.. ·14:37 R&D. On Bended Knee / Boyz II Men :>Track 4 Commercials: :30 U.S. Air Force :30 Visa :60 Tide Outcue: " ... wash-day blues." Local Break 1 :00 I ·rS~g 5 • 4:54 · Content: #13. Reach. For The Light/ Steve Winwood > Track 5 •·•··· · · Outcue: Jingle into music bed for local ID Insert local ID over :06 jingle bed J)Y/.\ V/1.(f WESTWOOD ONE ENTERTAINMENT 9540 Washington Boulevard • Culver Ciry, California 90232-2689 • (310} 204-5000 Content: #12. Keep Me From The Cold / Curtis Stigers EXT. -

Resolution No

City Council City of Philadelphia Chief Clerk's Office 402 City Hall Philadelphia, PA 19107 RESOLUTION NO. 170484 Introduced May 11, 2017 Councilmembers Johnson and Squilla RESOLUTION Also naming Broad Street from Christian Street to Carpenter Street “Boyz II Men Boulevard” to recognize and honor of Boyz II Men’s legacy as an iconic R&B group and an example to Philadelphia’s aspiring musical artists. WHEREAS, Boyz II Men, comprised of Nathan Morris, Shawn Stockman, and Wanya Morris, began their career rehearsing and performing in talent shows at the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts, which is located on the 900 block of South Broad Street, between Christian and Carpenter Streets; and WHEREAS, Boyz II Men’s first album, “Cooleyhighharmony”, featured the single “Motownphilly”, which topped the Pop and R&B charts and became their first certified Platinum single, selling over one million copies. The album also included the chart- topping and certified Gold ballad, “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday”; and WHEREAS, In 1992, Boyz II Men released their single “End of the Road”, which would sit atop the Billboard Hot 100 chart for a record-setting 13 weeks, breaking a decades-old record held by Elvis Presley. “End of the Road” garnered international success, elevating the up-and-coming group to celebrity status; and WHEREAS, Boyz II Men proceeded to break their own record with the releases of “I’ll Make Love to You” and “One Sweet Day”, topping the charts for 14 and 16 weeks, respectively. “One Sweet Day” continues to this day to hold the record for most weeks at number one. -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

Pdf, 312.59 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs. 00:00:05 Oliver Wang Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:07 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes 00:00:09 Oliver Host Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock, hot lava. And today we are going to be joining hands to take it back to 1994 and Two—or maybe it’s just II, I don’t know—the second album by the R&B mega smash group, Boyz II Men. 00:00:30 Music Music “Thank You” off the album II by Boyz II Men. Smooth, funky R&B. (I like this, I like this, I like...) I was young And didn't have nowhere to run I needed to wake up and see (and see) What's in front of me (na-na-na) There has to be a better way Sing it again a better way To show... 00:00:50 Morgan Host Boyz II Men going off, not too hard, not too soft— [Oliver says “ooo” appreciatively.] —could easily be considered a bit of a mantra for Shawn, Wanya, Nathan, and Michael, two tenors, a baritone, and a bass singer from Philly, after their debut album. The one that introduced us to their steez, and their melodies. This one went hella platinum. The follow-up, II. This album had hits that can be divided into three sections. Section one, couple’s therapy. -

ARTIST SONG 112 Cupid 112 Peaches and Cream a Taste of Honey Boogie Oogie, Oogie Aaliyah at Your Best Abba Dancing Queen After 7 Can't Stop Ah Ha Take on Me Al B

ARTIST SONG 112 Cupid 112 Peaches And cream A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie, Oogie Aaliyah At Your Best Abba Dancing Queen After 7 Can't Stop Ah Ha Take On Me Al B. Sure Nite And Day Al Green Here I Am (Come And Take Me) Al Green How Can You Mend A Broken Heart Al Green I'm Still In Love With You Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green Tired Of Being Alone Al Jarreau After All Al Jarreau Morning Al Jarreau Were In This Love Together Al Wilson Show And Tell Alabama Mountain Music Alan Jackson Chattahoochie Alicia Bridges I Love The Night Life All-4-One I Swear Arrested Development Mr.Wendal Average White Band Cut The Cake B.J. Thomas Raindrops Keep Fallin On My Head B.J. Thomas Wont You Play Another Somebody….. Babyface Everytime I Close My Eyes Babyface For The Cool In You Babyface Never Keeping Secrets Babyface When Can I See You Babyface Whip Appeal Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin Care Of Business Bachman-Turner Overdrive You A'int Seen Nothin Yet Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreets Back) Backstreet Boys Larger Than Life Barbra Streisand The Way We Were Bar-Kays, The Shake You Rump To The Funk Barry Manilow Copacabana Barry Manilow I Write The Songs Barry White Ectasy, When You Lay Next to Me Barry White Practice What You Preach Barry White Your The First, The Last, My Everything Beach Boys, The Surfin' USA Beatles, The A Day In The Life Beatles, The Come Togeter Beatles, The Do You Want to Know A Secret Beatles, The Eight Days a Week Beatles, The Nowhere Man Beatles, The The Long And Winding Road Beatles, The Twist And Shout Bee Gees, The How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees, The How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees, The Jive Talkin' Bee Gees, The Night Fever Bee Gees, The Stayin Alive Bee Gees, The Too Much Heaven Bee Gees, The Tragety Bee Gees, The You Should Be Dancin Bell Biv DeVoe Do Me Ben E. -

Domopalooza 2019 After Hours Announces Boyz II Men As Entertainment Headliner

Domopalooza 2019 After Hours Announces Boyz II Men as Entertainment Headliner January 30, 2019 SILICON SLOPES, Utah, Jan. 30, 2019 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Today Domo (Nasdaq: DOMO) announced that legendary R&B group Boyz II Men will perform at the Domopalooza After Hours. Spanning over two decades of hits and dozens of major accolades which include four Grammys, nine American Music Awards, nine Soul Train Awards, three Billboard Awards, and a 2011 MOBO Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, as well as a Casino Entertainment Award for their acclaimed residency at the Mirage Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, which has been ongoing since 2013, Boyz II Men won fans all over the world with megahits such as “End of the Road,” “On Bended Knee,” “One Sweet Day,” and “Motownphilly.” “During the day, we're offering a fantastic lineup of keynote and customer speakers. At night, we’re bringing incredible artists like Boyz II Men for entertainment. Domopalooza AfterHours will offer attendees a chance to unwind after a full day of unparalleled education, training and networking opportunities,” said Josh James, Domo founder and CEO. In its fifth year, Domopalooza is designed to educate, inform and inspire Domo’s fast-growing community of users from some of the world’s most progressive organizations and recognizable brands around the globe. Domopalooza will be held March 19-22, 2019, at the Salt Palace Convention Center in Salt Lake City. Domo recently announced the first of its much-anticipated lineup of Domopalooza keynotes speakers with renowned cybersecurity and IT executive Tony Scott. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino – with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s – and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the songwriting royalties for the rest of his life! Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ which Kris Kristofferson committed to record. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987. -

Hoddeson L., Kolb A.W., Westfall C. Fermilab.. Physics, the Frontier, And

Fermilab Fermilab Physics, the Frontier, and Megascience LILLIAN HODDESON, ADRIENNE W. KOLB, AND CATHERINE WESTFALL The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London LILLIAN HODDESONis the Thomas M. Siebel Professor of History of Science at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. ADRIENNE W. KOLBis the Fermilab archivist. CATHERINE WESTFALLis visiting associate professor at Lyman Briggs College at Michigan State University. Illustration on pages xii–xiii: Birds in flight over the Fermilab prairie. (Courtesy of Angela Gonzales.) Illustration on closing pages: Reflections of the Fermilab frontier. (Courtesy of Angela Gonzales.) The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-34623-6 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-34623-4 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hoddeson, Lillian. Fermilab : physics, the frontier, and megascience / Lillian Hod- deson, Adrienne W. Kolb, and Catherine Westfall. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-34623-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-34623-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory—History. 2. Particle accelerators—Research—United States. 3. Particles (Nuclear physics)—Research—United States I. Kolb, Adrienne W. II. Westfall, Catherine. III. Title. QC789.2.U62.F474 2008 539.730973—dc22 2008006254 ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Luke I Wanna Rock 4:23 Luke - Greatest Hits 8 1996 Rap 128 Disk Local 2 Angie Stone No More Rain (In this Cloud) 4:42 Black Diamond 1999 Soul 3 128 Disk Local 3 Keith Sweat Merry Go Round 5:17 I'll Give All My Love to You 4 1990 RnB 128 Disk Local 4 D'Angelo Brown Sugar (Live) 10:42 Brown Sugar 1 1995 Soul 128 Disk Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is Local 5 X Clan 4:45 To the East Blackwards 2 1990 Rap 128 It? Disk Local 6 Gerald Levert Answering Service 5:25 Groove on 5 1994 RnB 128 Disk Eddie Local 7 Intimate Friends 5:54 Vintage 78 13 1998 Soul 4 128 Kendricks Disk Houston Local 8 Talk of the Town 6:58 Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon 6 1998 Jazz 3 128 Person Disk Local 9 Ice Cube X-Bitches 4:58 War & Peace, Vol.1 15 1998 Rap 128 Disk Just Because God Said It (Part Local 10 LaShun Pace 9:37 Just Because God Said It 2 1998 Gospel 128 I) Disk Local 11 Mary J Blige Love No Limit (Remix) 3:43 What's The 411- Remix 9 1992 RnB 3 128 Disk Canton Living the Dream: Live in Local 12 I M 5:23 1997 Gospel 128 Spirituals Wash Disk Whitehead Local 13 Just A Touch Of Love 5:12 Serious 7 1994 Soul 3 128 Bros Disk Local 14 Mary J Blige Reminisce 5:24 What's the 411 2 1992 RnB 128 Disk Local 15 Tony Toni Tone I Couldn't Keep It To Myself 5:10 Sons of Soul 8 1993 Soul 128 Disk Local 16 Xscape Can't Hang 3:45 Off the Hook 4 1995 RnB 3 128 Disk C&C Music Things That Make You Go Local 17 5:21 Unknown 3 1990 Rap 128 Factory Hmmm Disk Local 18 Total Sittin' At Home (Remix) -

Topical Promo$ Topical Promo$ Fob Show #46 Abe Located on Pisc 4

WITH SHADOE STEVENS TOPICAL PROMO$ TOPICAL PROMO$ FOB SHOW #46 ABE LOCATED ON PISC 4. TRACKS 10.11 & 12. PO NOT USE AfTER SHOW 146 AT40 ACTUALITIES ABE LOCATED ON DISC 4. TRACKS 13.14 115. IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING TOPICAL PROMO$ ****AT 40 SNEAK PEEK. LOC·ATED ON DISC 4. TRACK 16**** 1. MELISSA'S DEVIL OR ANGEL. A DEADEYE AlJDIDON :29 Hi, Shadoe Stevens, AT40 bringing you the latest from music's hottest stars. last week. Melissa Etheridge talked about 'Devils & Angels,' and why both end up in her songs ... The band Deadeye Dick told us about a video audition for their hit song that brought out an incredible 100.thousand "New Age Girts.• We also found out about Jon Secada's first public singing performance in a musical production of Chartes Dickens' "A Christmas Caror. Hey, we've to hits and more for all seasons· right here- every week- on American Top 401 [LOCAL TAG] 2. GLORIA'S OLDIES AND THE ONE MILLION DOLLAR CONCERT :H Hey, Shadoe Stevens, American Top 40, bringing you all the latest on the wortd of Pop Music. Last week, we looked at Gloria Estefan's new album with remakes of her favorite qldies. We learned how the new band Hootie and The Blowfish found the unusual name • from the nickname's o~ two friends ... And in AT 40 Music News ... The superstar offered one million dollars to do just one concert in BeijinQ, China • Whitney Houston. Join me for the stars, their stories, the biggest hits of the week and much more· righ¢ here· on American Top 401 [LOCAL TAG] 3.