Inquiry Into Oaths and Affirmations with Reference to the Multicultural Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judges' Annual Report

Supreme Court of Victoria 2002–04 Annual Report SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA 2002–04 JUDGES’ ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS LETTER TO THE GOVERNOR Court Profile 1 To His Excellency Year at a Glance 2 The Honourable John Landy, AC, MBE Report of the Chief Justice 3 Governor of the State of Victoria and its Chief Executive Officer’s Review 7 Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia Court of Appeal 10 Dear Governor Trial Division: Civil 13 We, the Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria have the honour to present our Annual Report Trial Division: Commercial and Equity 18 pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial years of Trial Division: Common Law 22 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2003 and 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2004, including a transitional 18-month Trial Division: Criminal 24 Judges’ Report, reflecting the change in reporting period from calendar year to financial year. Masters 26 Funds in Court 29 Court Governance 31 Yours sincerely Judicial Organisational Chart 33 Judicial Administration 34 Court Management 36 Service Delivery 37 The Victorian Jury System 40 Marilyn L Warren The Court’s People 42 Chief Justice of Victoria Community Access 43 10 May 2005 Finance Report 2002–03 and 2003–04 45 Senior Master’s Special Purpose Financial Report for the John Winneke, P P D Cummins, J D J Habersberger, J Year Ended 30 June 2003 50 W F Ormiston, J A T H Smith, J R S Osborn, J Senior Master’s Special Purpose Stephen Charles, J A David Ashley, J J A Dodds-Streeton, J Financial Report for the F H Callaway, J A John -

Issues Paper on Consolidation of Evidence Legislation

Issues Paper Number 3 Consolidation of evidence legislation (LRC IP 3-2013) This is the third Issues Paper published by the Law Reform Commission. The purpose of an Issues Paper is to provide a summary or outline of a project on which the Commission is embarking or on which work is already underway, and to provide readers with an opportunity to express views and to make suggestions and comments on specific questions. The Issues Papers are circulated to members of the legal professions and to other professionals and groups who are likely to have a particular interest in, or specialist knowledge of, the relevant topic. They are also published on the Commission’s website (www.lawreform.ie) to ensure they are available to all members of the public. These Issues Papers represent current thinking within the Commission on the various items mentioned. They should not be taken as representing settled positions that have been taken by the Commission. Comments and suggestions are warmly welcomed from all interested parties and all responses will be treated in the strictest confidence. These should be sent to the Law Reform Commission: via email to [email protected] with the subject line Evidence or via post to IPC House, 35-39 Shelbourne Road, Dublin 4, marked for the attention of Evidence Researcher We would like to receive replies no later than close of business on 13th September 2013 if possible. ACTS CONSIDERED IN THIS ISSUE PAPER 1. WITNESSES ACT 1806 (REPEAL WITH RE-ENACTMENT PROPOSED) 2. EVIDENCE ACT 1843 (REPEAL WITH PARTIAL RE-ENACTMENT PROPOSED) 3. -

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE

Page 1 Halsbury's Laws of England (3) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE CROWN AND THE JUDICIARY 133. The monarch as the source of justice. The constitutional status of the judiciary is underpinned by its origins in the royal prerogative and its legal relationship with the Crown, dating from the medieval period when the prerogatives were exercised by the monarch personally. By virtue of the prerogative the monarch is the source and fountain of justice, and all jurisdiction is derived from her1. Hence, in legal contemplation, the Sovereign's Majesty is deemed always to be present in court2 and, by the terms of the coronation oath and by the maxims of the common law, as also by the ancient charters and statutes confirming the liberties of the subject, the monarch is bound to cause law and justice in mercy to be administered in all judgments3. This is, however, now a purely impersonal conception, for the monarch cannot personally execute any office relating to the administration of justice4 nor effect an arrest5. 1 Bac Abr, Prerogative, D1: see COURTS AND TRIBUNALS VOL 24 (2010) PARA 609. 2 1 Bl Com (14th Edn) 269. 3 As to the duty to cause law and justice to be executed see PARA 36 head (2). 4 2 Co Inst 187; 4 Co Inst 71; Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63. James I is said to have endeavoured to revive the ancient practice of sitting in court, but was informed by the judges that he could not deliver an opinion: Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63; see 3 Stephen's Commentaries (4th Edn) 357n. -

South Australia Law Reform Institute

Issues Paper 3 October 2013 South Australian Law Reform Institute Nothing but the truth Witness oaths and affirmations The South Australian Law Reform Institute was established in December 2010 by agreement between the Attorney-General of South Australia, the University of Adelaide and the Law Society of South Australia. It is based at the Adelaide University Law School. Postal address: SA Law Reform Institute Adelaide Law School University of Adelaide North Terrace Adelaide SA 5005 Contact details: (08) 8313 5582 [email protected] www.law.adelaide.edu.au/reform/ Publications All SALRI publications, including this one, are available to download free of charge from www.law.adelaide.edu.au/reform/publications/ If you are sending a submission to SALRI on this Issues Paper, please note: the closing date for submissions is Friday 17 January 2014; there is a questionnaire in downloadable form at www.law.adelaide.edu.au/reform/publications/ we would prefer you to send your submission by email; we may publish responses to this paper on our webpage with the Final Report. If you do not wish your submission to be published in this way, or if you wish it to be published anonymously, please let us know in writing with your submission. The cover illustration is from The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay. The eBook may be read or downloaded from <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/23625/23625- h/23625-h.htm> Contents ABBREVIATIONS 2 PARTICIPANTS 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 TERMS OF REFERENCE 4 OVERVIEW 4 1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND -

Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 ————————

———————— AN BILLE UM ATHCHO´ IRIU´ AN DLI´ REACHTU´ IL 2007 STATUTE LAW REVISION BILL 2007 ———————— Mar a tionscnaı´odh As initiated ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 [No. 5 of 2007] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas., 1. c. 3 General Pier and Harbour Act 1861 Amendment Act 1862 25 & 26 Vict., c. -

Journal Malaysian Judiciary

JOURNAL JOURNAL OFJOURNAL JUDICIARY MALAYSIAN THE OF THE MALAYSIAN JUDICIARY July 2020 January 2019 Barcode ISSN 0127-9270 JOURNAL OF THE MALAYSIAN JUDICIARY July 2020 JOURNAL OF THE MALAYSIAN JUDICIARY MODE OF CITATION Month [Year] JMJ page ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Publication Secretary, Judicial Appointments Commission Level 5, Palace of Justice, Precinct 3, 62506 Putrajaya www.jac.gov.my Tel: 603-88803546 Fax: 603-88803549 2020 © Judicial Appointments Commission, Level 5, Palace of Justice, Precinct 3, 62506 Putrajaya, Malaysia. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any material form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature. Views expressed by contributors in this Journal are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Malaysian Judiciary, Judicial Appointments Commission or Malaysian Judicial Academy. Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure that the information contained in this work is correct, the publisher, the editor, the contributors and the Academy disclaim all liability and responsibility for any error or omission in this publication, and in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done by any person in reliance, whether wholly or partially, upon the whole or any part of the contents of this publication. -

Oaths Act 1978, Part II

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Oaths Act 1978, Part II. (See end of Document for details) Oaths Act 1978 1978 CHAPTER 19 PART II UNITED KINGDOM Oaths 3 Swearing with uplifted hand. If any person to whom an oath is administered desires to swear with uplifted hand, in the form and manner in which an oath is usually administered in Scotland, he shall be permitted so to do, and the oath shall be administered to him in such form and manner without further question. Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Court Martial Appeal Court Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/2657), rule 15, Sch. 1 C2 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Court Martial) Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/2041), rule 21 C3 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Summary Hearing and Activation of Suspended Sentences of Service Detention) Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/1216), rule 14 C4 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Summary Appeal Court) Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/1211), rule 28 C5 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Service Civilian Court) Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/1209), rule 20 C6 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Warrants of Arrest for Service Offences) Rules 2009 (S.I. 2009/1110), rule 16 C7 S. 3-6 applied (with modifications) (31.10.2009) by The Armed Forces (Custody Proceedings) Rules 2009 (S.I. -

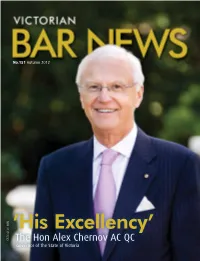

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

The Forensic Exhibit 2020

ANZFEC Australia New THE Zealand ADVIC CWALN Biology Chemical Criminalistics Crime Scene Ballistics Document Examination Electronic Evidence Fingerprints Illicit Drugs Medical Sciences Toxicology Standards Coordination Innovation Quality Information Management Education Training After the Fact Certification Peak Body DNA Analysis Facial Identification Speaker Recognition Fire Debris and Explosives Geological Materials Friction Ridge Firearms Toolmarks Tyre & Shoemark Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Odontology FORENSIC Anthropology Digital Evidence Audio Visual Computer Forensics Digital Imaging Entomology Mortuary Statistics MPS YSTR Forecasting Emerging Challenges Informing Best Practice Opportunities to Collaborate and Leverage Resources Discipline Specific Technical Advice Capability Development Inform Strategic Policy Support Research Information Exchange Promote and Facilitate Excellence in Forensic Science ANZFEC Australia New Zealand ADVIC Volume 3 CWALN Biology Chemical Criminalistics Crime Scene Ballistics Document Examination Electronic Evidence Issue 3 Fingerprints Illicit Drugs Medical Sciences Toxicology Standards Coordination Innovation Quality Information Management Education Training After the Fact Certification Peak Body DNA Analysis Facial Identification Speaker September 2020 EXHIBIT Recognition Fire Debris and Explosives Geological Materials Friction Ridge Firearms Toolmarks Tyre & Shoemark Bloodstain Shining a spotlight on the work of the Australia New Zealand forensic science community Your NIFS Team Member Update forensic services including forensic biology (incl. DNA analysis) and fingerprints. The NIFS team wish to congratulate Rob on this The next stage of the fundamentals appointment and wish his all the best in his project is in full swing with a new group of new role. He will be missed. experts for both the audio video and drug analysis disciplines coming on board Rob and wife Sophie also recently to this valuable initiative. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 31 August 2010 (Extract from book 12) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Minister for Multicultural Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Deputy Premier, Attorney-General and Minister for Racing............ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Treasurer, Minister for Information and Communication Technology, and Minister for Financial Services.............................. The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Regional and Rural Development, and Minister for Industry and Trade............................................. The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Health............................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Energy and Resources, and Minister for the Arts........... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services, and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Community Development.............................. The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Small Business.............. The Hon. J. Helper, MP Minister for Finance, WorkCover and the Transport Accident Commission, Minister for Water -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 09:38:16AM Via Free Access

journal of law, religion and state 6 (2018) 195-212 brill.com/jlrs The Rule of Law, Religious Authority, and Oaths of Office Nicholas Aroney The University of Queensland [email protected] Abstract The rule of law requires political office holders to exercise their powers in accordance with the law. Most societies, however, rely not only on the moral obligation to obey the law but also require office holders to take a religious oath or solemn affirmation. The divine witness to the oath of office stands in as a guarantor of the political order but also looms above it. As such, the oath represents a paradox. It guarantees the performance of official duties while also subjecting them to external judgement. The oath thus encompasses the large question of the relationship between religious con- viction, personal fidelity, moral principle, and political power. It suggests that law and religion are as much intertwined as separated in today’s politics. By tracing the oath of office as a sacrament of power, much light can be shed on the relationship between law and religion in today’s liberal-democratic politics. Keywords oath – office – religion – law – faith – power – secular 1 Introduction The rule of law means, among other things, that those who hold political of- fice are required to exercise their powers and perform their official duties in accordance with the law. Most liberal-democratic societies, however, do not rely only on the proposition that office holders are morally obligated or legally compelled to comply with the law. Typically, such societies also require office holders to take a religious oath, or at least a solemn affirmation, in which they publicly promise to fulfill their duties in accordance with the law. -

Oaths Act 1978 CHAPTER 19

Oaths Act 1978 CHAPTER 19 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I ENGLAND, WALES AND NORTHERN IRELAND Section 1. Manner of administration of oaths. 2. Consequential amendments. PART II UNITED KINGDOM Oaths 3. Swearing with uplifted hand. 4. Validity of oaths. Solemn affirmations 5. Making of solemn affirmations. 6. Form of affirmation. Supplementary 7. Repeals and savings. 8. Short title, extent and commencement. SCHEDULE-Repeals. Part I-Consequential repeals. Part II-Repeal of an obsolete enactment. ELIZABETH II c. 19 Oaths Act 1978 1978 CHAPTER 19 An Act to consolidate the Oaths Act 1838 and the Oaths Acts 1888 to 1977, and to repeal, as obsolete, section 13 of the Circuit Courts (Scotland) Act 1828. [30th June 1978] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I ENGLAND, WALES AND NORTHERN IRELAND 1.-(1) Any oath may be administered and taken in England, Manner of and administration Wales or Northern Ireland in the following form manner:- of oaths. The person taking the oath shall hold the New Testa- ment, or, in the case of a Jew, the Old Testament, in his uplifted hand, and shall say or repeat after the officer administering the oath the words " I swear by Almighty God that ...... ", followed by the words of the oath pre- scribed by law. (2) The officer shall (unless the person about to take the oath voluntarily objects thereto, or is physically incapable of so taking the oath) administer the oath in the form and manner aforesaid without question.