Years of Rice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rice Thresher

Athletics Review Committee members v , * ?: Ralph O'Connor Troy Squires W.G. Characklis Catherine Hannah Richard Chapman Ira Gruber John Anderson Pro-athletic sentiment dominates open meeting by BARRY JONES questions and suggestions afford to compete? At the profitable one. revenue program. from members of the Rice meeting, it was never made The committee has studied One of the more pervasive The University Athletics community. The committee clear whether that was the sample budgets from several topics was the "sheltered Review Committee held an was formed by Dr. Hacker- committee's purpose, or schools, some of which have program." a major which is open meeting in Sewall Hall man. Most people have whether the question was if dropped athletics, some of open only to varsity athletes Monday night. The purpose of assumed that the underlying Rice should have an athletic which have cut back and even and which might be below the meeting was to field motive was financial: can Rice program at all, even a one that conducted a non- normal university standards. The Commerce Department Rice's entry in the sheltered program field, is currently being phased out. The consensus was that Rice should not operate under an academic double standard; the rice thresher also, the athlete should not be thursday, march 18, 1976 volume 63, number 44 herded into a program he didn't particularly care for just to keep his eligibility up. It was also suggested that Rice turns SA concurs with report, approves Pierce off many recruits because there is no actual business by KIM D. -

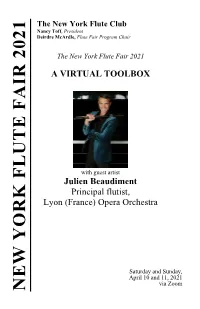

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

Athletic Heritage

R Athletic Heritage Athletic Highlights • Morris Almond, was the 25th pick in the • Rice has won individual national titles in • The first NCAA team championship for first round by the Utah Jazz in the 2007 men’s tennis (two singles and two doubles), Rice, occurred in 2003, when the Owls won NBA Draft. He became the first Rice Owl to women’s tennis (doubles), men’s track and the College World Series. be selected in the first round since Ricky field and women’s track and field. Pierce was the 18th overall pick in the 1982 • The 1946 football Owls were Southwest NBA Draft by the Detroit Pistons. Almond is • The Owls have won a total of 75 Conference co-champions and went on to one of 20 men’s basketball players to play conference titles. defeat Tennessee in the Orange Bowl. professionally since 1992. • 495 Owls have earned All-America • In 2000, Rice won an unprecedented • Team captain Larry Izzo has won three honors. six Western Athletic Conference titles. Super Bowl rings as a member of the New The Owls were victorious in women’s England Patriots. More than 50 Owls have • Rice has been represented at 11 Olympics basketball, men’s and women’s cross played in the NFL. by 20 different athletes, dating back to the country, women’s indoor and outdoor track 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. and field, and baseball. • Rice’s women’s basketball team has been to the “Big Dance” twice after winning the • A total of 16 Owls have been drafted in 2000 and 2005 WAC Championship to earn the first round by Major League Baseball the league’s NCAA automatic bid. -

2019 Gala Auction Program

2019 Friends of Fondren Library Gala HONORING PHOEBE AND BOBBY TUDOR ’82 Auction Program The Friends of Fondren Library and Amy and Robert Taylor, Gala Chairs welcome you to The 2019 Friends of Fondren Library Gala honoring Phoebe and Bobby Tudor ’82 To place a Auctionbid on a silent auctionProgram item, adhere and your Guidelinespersonal bar code next to the bid amount on the bidding sheet. Please be sure that the number on the item corresponds with the number on the bid sheet. The value, minimum bid and bid increments are listed on each bid sheet. Be careful not to place your bar code sticker on top of another bidder’s sticker. Payment in full by cash, check, MasterCard, Visa, American Express or Discover is required at the end of the evening. You will be issued a receipt for your tax records. All portable items must be removed at the conclusion of the evening. Arrangements must be made for the removal of any large items. Neither the committee nor the Friends of Fondren Library assumes responsibility for the condition of the items. No guarantee, except that of the manufacturer if applicable, is either expressed or implied. All items in this auction have been donated for the 2019 Friends of Fondren Library Gala event and cannot be exchanged. The advertised minimum bid is the lowest price at which a bidder can purchase the item. If the minimum bid or reserve price of an item is not met, the Friends of Fondren Library is under no obligation to sell the item. Please note that many of the items are for specific dates or have expiration dates. -

Hale, Bost, Kopra Win; Thresher Vote May Be Reset by JOHN ANDERSON Student

Hale, Bost, Kopra win; Thresher vote may be reset by JOHN ANDERSON student. Nakahara, Michael Dunn, Geor- Melissa Tyson, RPC Secretary- reports that candidates have now Winning with almost 56 per- The college dues referendum gian a Bolton, Debbie Wood- Treasurer; Janet Doty, Thresher filed for Campanile editor and cent of the vote, Hanszen junior (which would have raised those hatch, Nobie Cleaver, cheer- Business Manager; Michael J. for University Court Chairman. Wayne Hale defeated D. H. Wha- fees from $20 to $30) failed leaders; Susan Tresch, Barbara Smith, Campanile Business Those elections will be held len for SA President 648-514 in with three colleges, Brown, Ladner, Sophomore reps to the Manager; Rick Bost, Jerry Wood- March 11. Tuesday's general election. Richardson, and Will Rice voting Honor Council; Tom Glenn, ward, Joan Kelhof, and Frank The candidates for Campanile Rick Bost took the other con- no. Mark Bockeloh, and Margaret Zimba, Senior representatives to editor are Scott Senauke-Jose tested SA executive committee Other winning candidates in Jordan, Junior reps to the Honor the Honor Council. Abbenante (as co-editors) and race, defeating Gary Coover contested elections are: Kate Council. All three revisions of the Cynthia Anne Corley. Candi- 437-414 for External Affairs Wheeler and Barbara Morris, Off Winners unopposed included: Honor Council Constitution dates for Court Chairman in- Vice President. Campus Senator; Paul Hutter John Anderson, SA Internal passed. clude Stephen W. Collier, Robert In one of the closest elec- and David Huffman, University Affairs Vice President; Stephanie Marty Sosland, Internal Af- (Butch) Spaw, jr., Stafford Stew- tions, incumbent Thresher editor Council; Tom Hagemann, Asuka Knight, SA Secretary-Treasurer; fairs Vice President of the SA, art, and Austin Boyd. -

Snatching Gems from the Ash Heap: Saving the KTRU Tapes

NEWS FROM FONDREN Volume 25, No. 2 • Spring 2016 Snatching Gems From the Ash Heap: Saving the KTRU Tapes As Rice University’s student-run radio with contemporary musical shifts, from The digitization project is expected to station, KTRU, returns to the FM art rock in the 1970s to alternative, run until fall 2016, at which point phase broadcast spectrum, Fondren’s archivists experimental and underground rock in two will begin: digitizing the audio reels in the Woodson Research Center (WRC) the 1980s. The 1980s also brought the stored at KTRU. are racing to save historical broadcasts on addition of specialty shows, a tradition Audio already digitized includes crumbling analog media. that continues to this day with shows such on-campus talks and conversations with The project, which began in as the Mutant Hardcore Flower Hour Gene Roddenberry, Jacques Cousteau, September 2015, seeks to digitize the and four -hour jazz block every Sunday and Jerry Rubin; live on-air concerts 25 boxes of reel-to -reel audio tape that afternoon. Additionally, KTRU broadcast performed at Rice (including one with comprise the WRC’s archival collection Rice athletic events, interviews, public blues legends Sonny Terry and Brownie UA011, Rice University KTRU Radio lectures of Rice affiliates, concerts from McGhee); and backstage interviews with records. The collection contains news the Shepherd School of Music, and news notable ’70s performers, such as Mike broadcasts, political speeches, rock and events relating to the campus and Love of the Beach Boys, Billy Joel, Janis interviews and other unique content beyond. Ian, Peter Gabriel and Nick Lowe. -

The Shepherd School of Music at Rice University, Houston, TX

Fall 2013 Conference of the Southwest Chapter of the American Musicological Society Saturday, October 5, 2013 The Shepherd School of Music at Rice University in Houston, Texas Conference Host: Dr. Peter Loewen AMS–SW CONFERENCE OCTOBER 5, 2013 HOSTED BY THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC RICE UNIVERSITYHOUSTON, TEXAS Directions to the Shepherd School of Music Travel by Air: You may fly into either Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) or Hobby Airport (HOU) and rent a car. Travel by Car: Rice University is located southwest of the city center, and may be approached from three major thoroughfares: highways 59 and 288, and the 610 freeway. From Bush Intercontinental Airport: Take Beltway 8 east to Highway 59. Follow Highway 59 south to the Greenbriar exit (you will pass the 610, I-10 and I-45 before you reach Greenbriar). Upon exiting, go south (left) on Greenbriar to Rice Boulevard. Turn left onto Rice Boulevard. The Rice campus will be on your right. From Hobby Airport: Take the main airport exit, which is Broadway Boulevard. Follow Broadway Boulevard to I-45. Follow I-45 north to Highway 59. Follow Highway 59 south to the Greenbriar exit. Upon exiting, go south (left) on Greenbriar to Rice Boulevard. Turn left onto Rice Boulevard. The campus will be on your right. Parking Information The conference will take place in Room 1131 of the Shepherd School of Music (Alice Pratt Brown Hall), located directly east of Rice Stadium (see map below). There are several paid visitor parking lots located nearby the Shepherd School. These require a credit card, except for the Central Campus Garage, located under the Jesse H. -

2008-09 Rice Men's Tennis Media Guide

INTRODUCTION GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents & Quick Facts ...............................................................1 Location ............................................................................... Houston, Texas Mission Statement .......................................................................................2 Enrollment ..............................................................................................5,145 Conference USA...........................................................................................2008-09 RICE MEN’S3 TENNISFounded ............................................................ MEDIA GUIDE 1891 (First classes in 1912) Jake Hess Tennis Stadium .........................................................................4 Nickname ...............................................................................................Owls Schedule........................................................................................................5 Mascot .................................................................................Sammy the Owl Outlook ...........................................................................................................6 Colors ..................................................................................... Blue and Gray Frank Guernsey Captain Award .................................................................7 President .........................................................................David W. Leebron Roster .............................................................................................................8 -

Mezzo-Soprano Yungee Rhie, Soprano

ROSEMARY HYLER RITTER Founder/Artistic Director Matthew Morris and Liza Stepanova Associate Artistic Directors “Bright is the ring of words when the right man rings them.” – Robert Lewis Stevenson THE COMPLETE RECITALIST MAY 31-JUNE 28, 2014 The Stern Fellowship Program for Singers and Pianists has generously been funded by The Marc and Eva Stern Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Stern family! SongFest is thrilled to announce that two well-known members of our community have joined the artistic team as associate artistic directors this season: Matthew Morris, baritone (Stern Fellow ’10 and Faculty ’12,’13) and Liza Stepanova, pianist (Stern Fellow ’09 & ’10, Faculty ’11,’12, and ‘13). As a program dedicated to the unique marriage of poetry and music brought to life by a singer and a pianist, SongFest could not imagine a better team than these artists who both attended the program as participants and returned each year thereafter as faculty. Matthew has a unique performing career that combines recital (he most recently made his Kennedy Center debut as the winner of the Vocal Arts DC competition), concert (debuts with the London, American, Boston, and MDR Leipzig Symphony Orchestras), opera (including New York City Opera and Santa Fe Opera), theater (the Bouffes du Nord in Paris, West End, and Piccolo Teatro in Milan), and film and television (The Producers and Law & Order). He trained at the Juilliard School, at the Bard Conservatory with Dawn Upshaw, and with Peter Brook and Marcello Magni of the Lecoq school. We are honored that he shares his breadth and depth of experience each summer with our singers as Director of the Young Artist Program. -

53 Academics

O-Week Jones College The Rice Experience 53 Academics University Resources Wellness & Diversity Student Life Student Houston and Beyond Academics Academic Advising Your next four years at Rice will be an incredible experience, but you have to get an education at some point, right? Switching from a high school to a college curriculum can be kind of a scary transition, but have no fear! Rice has a number of well-trained faculty, staff and students to help you with your academic transition. A lot of your initial questions will be answered during O-Week, through presentations and academic planning sessions, in time for you to register for classes during orientation week. There is a list of people that are available for your entire career at Rice. They are a great resource and can really help you succeed in your first year and beyond. Divisional Advisors During O-Week, you will have a chance to meet with a faculty advisor within your school of interest, which you designated on your academic questionnaire this summer. He or she will give you general guidance with- in your division of study. These faculty advisors are a great resource for questions on academic rules, regulations and policies, general graduation requirements, campus resources, current educational opportunities for students, course planning, major considerations, study abroad, and other Rice and non-Rice opportunities. Your divisional advisor doesn’t serve as a resource only during O-Week, though. You can continue to meet with your divisional advisor after O-Week and even after you decide on a major. Plus, these advisors are associates at Jones, which means they often come hang out at the college at lunch or during Associates Night. -

Origins of the Experimental Music Studios at Illinois: the Urbana School from the Dean

WINTER 2009 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music origins of the experimental music studios at illinois: the urbana school From the Dean The School of Music is one of the most respected and visible units in the College of Fine and WINTER 2009 Applied Arts at the University of Illinois, and it is Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music also a vital component of what we are calling the at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign new arts at Illinois, our vision of the college as a The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana- leader in the arts of the future. Champaign and has been an accredited institutional member of the National Association of Schools of Music Throughout the college, we are exploring new since 1933. disciplinary combinations, new definitions of art, and new ways of thinking Karl Kramer, director Edward Rath, associate director and creating. At the same time, we maintain a profound commitment to the Paul Redman, assistant director, business Joyce Griggs, assistant director, enrollment management historical traditions of our art forms. We embrace the notion that the knowl- and public engagement Marlah Bonner-McDuffie, director, development edge arising from the study, interpretation, and creation of art is central to Philip Yampolsky, director, Robert E. Brown Center for World Music the intellectual enterprise of a great university and to the advancement of a David Allen, coordinator, outreach and public engagement great society. Michael Cameron, coordinator, graduate studies B. -

Yale's Pelli Proposes New Master Plan for Rice by Robert Stoy Discussed Rice's More Immediate Next to the Chemistry Lecture Hall

K c / A/v i X Yale's Pelli proposes new master plan for Rice by Robert Stoy discussed Rice's more immediate next to the Chemistry lecture hall. to accommodate on-campus doubts. Larry Livingston, Dean of Architect Cesar Pelli presented a expected needs. These were a new A lecture and recital hall, seating meetings and house guests of the the Shepherd School, found Pelli's long-range plan for the Rice engineering building, a biochem- 300-400 people and placed across university. answer to a music school building campus last Thursday in the istry building, a building for the from the west facade of Anderson Still further in the future was a "very elegant" but inadequate in Chemistry Lecture Hall. Its Shepherd School of Music, and Hall and next to Fondren Library, possible 10,000-seat sports arena one major respect. He called its purpose, he stated, was to provide the expansion of the Rice would be shared by the Shepherd situated adjacent to commuter location near Hamman Hall "very future guidance for the location of Memorial Center. School and other departments. parking lot F and a 1,000 to 1,200- perplexing" because, though new buildings at Rice. In his In Pelli's design, the new Pelli's plan provided for seat orchestra hall situated on the Hamman Hall is now a primary discussion, however, Pelli omitted engineering wing would stand on expanding the RMC primarily to same axis with Lovett Hall and performance space, it "is totally a few of the campus's more the Mechanical Laboratory quad the west side, creating a courtyard Fondren, in what is now the unacceptable as a performance immediate needs, according to across from Abercrombie Lab, adjacent to Sammy's Cafeteria.