The Apparel and Footwear Supply Chain Transparency Pledge V“The Transparency Pledge”W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIK Textilien Und Non Food Gmbh

The following correspondence was received by way of e-mail on April 16, 2014 in reply to a Human Rights Watch letter e-mailed on April 4, 2014. Subject: Your letter of April 4th, 2014 addressing Mr. Stefan Heinig Dear Mr. Adams, many thanks for your letter of April 4th, 2014 addressing our former CEO Mr. Stefan Heinig, which has been forwarded to me as I am in charge with this matter. Please find enclosed our press statement on our contribution to the Rana Plaza Arrangement Donors Trust Fund. In the aftermath of the very tragic accident we started to develop projects addressing the needs of the people having suffered from the building collapse. In due course we will check with ILO if these projects can be offset with the Fund. At the same time we very much appreciated the joint approach designed and controlled by ILO. As one of the first brands we made a contribution to the fund and – this to hopefully instigate others - made our contribution public even telling the amount. Nonetheless we felt that we had to cling to our projects as our partners already had invested a lot of work and the Donors Trust Fund will only work efficiently, if many brands sourcing in Bangladesh will support it. Please let me have your findings on this issue and get back to me in case of any further questions. Many kind regards Britta Schrage-Oliva Sustainability affairs officer KIK Textilien und Non Food GmbH Press Release KiK supports Rana Plaza victims with US $ 1 Million Bönen, April 2nd 2014. -

Still Waiting: Six Months After History’S Deadliest Apparel Industry Disaster, Workers Continue to Fight for Compensation

STILL WAITING: Six months after history’s deadliest apparel industry disaster, workers continue to fight for compensation INTERNATIONAL LABOR RIGHTS FORUM STILL WAITING Still Waiting - Six months after history’s deadliest apparel industry disaster, workers continue to fight for reparations AUTHORS: Liana Foxvog, Judy Gearhart, Samantha PUBLISHED BY: Maher, Liz Parker, Ben Vanpeperstraete, Ineke Zeldenrust DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Kelsey Lesko, Clean Clothes Campaign – International Secretariat Haley Wrinkle P.O. Box 11584 1001 GN Amsterdam the Netherlands COVER PHOTO: Rokeya Begum shows a picture of T: +31 (0)20 4122785 her 18-year-old daughter Henna Akhtar, a seamstress [email protected] who died in the fire at Tazreen Fashions. Photo © www.cleanclothes.org Kevin Frayer, Associated Press. International Labor Rights Forum The authors of this report express gratitude to the authors of “Fatal 1634 I St. NW, Suite 1001 Fashion,” which has been used as the basis of the background information Washington, DC 20006 on Tazreen: Martje Theuws, Mariette van Huijstee, Pauline Overeem & USA Jos van Seters (SOMO), Tessel Pauli (CCC). “Fatal Fashion” is available at: T: +1 202 347 4100 http://www.cleanclothes.org/resources/publications/fatal-fashion.pdf/ [email protected] view and the authours of “100 Days of Rana Plaza,” which has been used as www.laborrights.org the basis for background on Rana Plaza: Dr K. G. Moozzem (CPD) and Ms Meherun Nesa (CPD). “100 Days of Rana Plaza” is available at http://cpd. SUPPORTED BY: org.bd/index.php/100-days-of-rana-plaza-tragedy/ This publication is made possible with financial assistance of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and of the European Union. -

MADRID Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

MADRID Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Madrid | 2019 0 The retail market in Madrid has two major hubs (Centro and Salamanca districts) where the greatest concentration of both national and international retailers can be found. There are also a number of key secondary locations including Princesa, Orense and Alcala Streets. The City of Madrid continues to renew itself and adapt to changing trading environments, such as the recent refurbishment along Serrano Street with improved pedestrian mobility. At the Centro district many streets have also seen the refurbishment of buildings and changing uses in order to accommodate new brands in the city centre, where in the past it has been difficult to find good quality retail space as well as suitable hospitality spaces. Barrio de Salamanca is one of the two most important commercial areas of Madrid. A considerable number of international retailers are located in this area. As a result, the diversity of the retail offer in this area makes it an ideal destination for tourists and customers seeking the many brands that trade here. Within the district there are key luxury streets, such as Ortega y Gasset, and also streets geared towards mass market, including Goya and Velázquez. Along the secondary streets, such as Claudio MADRID Coello, Lagasca, Jorge Juan and Ayala, a large number of premium brands also have a strong presence. Serrano acts as the main commercial artery of the neighbourhood OVERVIEW with the important luxury, premium and mass market brands concentrated along its two sidewalks. Barrio de Salamanca offers a wide mixture of commercial, cultural and gastronomic supply. -

KIK Moves to Gorkistraße

PRESS RELEASE 1/2 KIK moves to Gorkistraße Berlin, 12 February 2018 – In the spring of 2019, the textile discounter KIK opens a branch in the Tegel Quartier on Gorkistraße in Berlin-Tegel. On the first floor of the shopping and experience centre, KIK occupies a 780 sqm shop area. Families, mothers and bargain hunters will find a large selection of women's, men's, children's and baby clothes as well as laundry and stocking articles at low prices at KIK. In addition, KiK offers visitors to Gorkistraße a wide range of gift- and trend articles, stationery and toys as well as home textiles. The HGHI-Group is currently renovating and modernising the Tegel Center, the former Hertie House and the Gorkistraße on a large scale. In addition, the existing retail space will be expanded from 30,000 sqm to 50,000 sqm. With around 100 shops, the new Tegel Quarter offers visitors a varied mix of fashion, gastronomy, electronics and HGHI HOLDING GMBH Phone: +49 (0) 30 804 98 48-0 FOLLOW US: Mendelssohn-Palais Fax: +49 (0) 30 804 98 48-11 Jägerstraße 49/50 Mail: [email protected] 10117 Berlin Internet: www.hghi.de 2/2 About KiK Textiles and Non-Food GmbH KiK stands for "Kunde ist König" (Customer is king), the leading motif of the basic textile supplier since its founding in 1994, KiK Textilien und Non-Food GmbH offers high-quality ladies', men's, children's and baby clothing at the best price available. In addition to clothing, the range also includes gift articles, toys, beauty products, accessories and home textiles. -

The Case of Rana Plaza: a Precedent Or the Severe Reality? 1

The Case of Rana Plaza: A precedent or the severe reality? 1 Name of student: Radostina Velinova Programme: BA (Hons) Business Management Year of study: 2 Mentored by: Dr Wim Vandekerckhove Abstract This paper discusses supply chain responsibilities in the case of the Rana Plaza disaster. In 2013 the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing more than 1000 workers. They were garment workers for outsourced operations from well known Western fashion brands. A huge debate emerged around duties in outsourcing and offshoring operations. This paper first analyses some of the arguments accusing the fashion brands of conducting business in an irresponsible way. It then analyses the responses from these brands with regard to the allegations, and their subsequent policy changes. The analyses are informed by ethical theories and Ruggie’s work on due diligence in supply chain responsibilities. Key words: business ethics, due diligence, Ruggie, supply chain responsibilities, Rana Plaza, globalisation 1 This paper was also submitted for the Institute of Business Ethics Essay Prize 2014. 1 Introduction Bangladesh has long been known as a cheap outsourcing destination, often used as part of the global supply chains of many Western clothing companies. Nowadays, the country gains almost 80 per cent of its export earnings from the clothing factories there (Jacob 2012). There are severe examples of disasters, which prove the situation is puzzling. Undoubtedly, the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in 2013 killing more than 1000 workers affected not only the local community, but also the whole world – including top clothing brands, their employees and customers. It brought about serious discussions and questioned the business ethics of various well-known apparel organisations such as Primark, H&M, Zara, GAP, Benetton. -

Original Document (PDF)

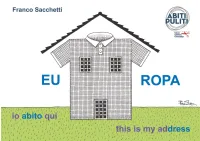

Written and drawn by Franco Sacchetti in collaboration with Clean Clothes Campaign translated by Christine Tracey (Eu) ropa is an artistic project of Insomnia Company supported by Iberescena and Electa Creative Arts www.franco sacchetti.it www.insomniaitalia.blogspot.com Dhaka, Bangladesh. Don’t be fooled, it isn’t snowing. It never snows in these parts. They look like snowflakes but they’re actually flecks of cotton... The cotton is carded and combed, and then transformed into thread. It’s a thread many lives depend on, in Bangladesh, just as elsewhere in the world... A thread so flexible it can take on any form, and so fine it can pass through the eye of a needle. It tells us an age-old story that we continue to ignore... The weft and the warp. The thread, woven through other threads, is transformed into cloth..... A cloth whose production can involve humiliation, imprisonment, slave-labour. In the worst cases, even death....... Like in the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, which we can ‘affectionately’ call Uncle Benetton’s Cabin. On 24 April 2013, 1138 people lost their lives here. It was the greatest industrial tragedy after Bhopal... 1138 people died so that you could look cool, wearing clothes for which you don’t pay the true price. 1138 people died. Most of them were women. Benetton isn’t the only brand name involved. In that building they also produced clothes for Walmart, El Corte Ingles, Inditex, Children’s Place, Primark, Joe Fresh (Loblaws), KiK, Bon Marché, Mascot, Adler, Auchan, Matalan, Lee Cooper, Carrefour and Mango, Manifattura Corona and Yes Zee. -

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry Updated August 3, 2015 COMPANY COUNTRY BANGLADESH ACCORD SIGNATORY FACTORY TRANSPARENCY COMPENSATION FOR TAZREEN FIRE VICTIMS COMPENSATION FOR RANA PLAZA VICTIMS BRANDS PARENT COMPANY NEWS/ACTION Cotton on Group Australia Y Designworks Clothing Company Australia Y Republic, Chino Kids Forever New Australia Y Kathmandu Australia K-Mart Australia Australia Y Licensing Essentials Pty Ltd Australia Y Pacific Brands Australia Y Pretty Girl Fashion Group Pty Australia Y Speciality Fashions Australia Australia Y Target Australia Australia Y The Just Group Australia Woolworths Australia Australia Y Workwear Group Australia Y Fashion Team HandelsgmbH Austria Y Paid some initial relief and C&A Foundation has committed to pay a Linked to Rana Plaza. C&A significant amount of Foundation contributed C&A Belgium Y compensation. $1,000,000 to the Trust Fund. JBC NV Belgium Y Jogilo N.V Belgium Y Malu N.V. Belgium Y Tex Alliance Belgium Y Van Der Erve Belgium Y Brüzer Sportsgear LTD Canada Y Canadian Tire Corporation Ltd Canada Giant Tiger Canada Discloses cities of supplier factories, but not full Anvil, Comfort Colors, Gildan, Gold Toe, Gildan Canada addresses. TM, Secret, Silks, Therapy Plus Contributed an undisclosed amount to the Rana Plaza Trust Hudson’s Bay Company Canada Fund via BRAC USA. IFG Corp. Canada Linked to Rana Plaza. Contributed $3,370,620 to the Loblaw Canada Y Trust Fund. Joe Fresh Lululemon Athletica inc. Canada Bestseller Denmark Y Coop Danmark Denmark Y Dansk Supermarked Denmark Y DK Company Denmark Y FIPO China, FIPOTEX Fashion, FIPOTEX Global, Retailers Europe, FIPO Group Denmark Y Besthouse Europe A/S IC Companys A/S Denmark Y Linked to Rana Plaza. -

Brands' Responses to Tazreen and Rana Plaza Compensation De

Update:View metadata, Brands' responses citation and to similar Tazreen papers and at Rana core.ac.uk Plaza compensation de... http://www.cleanclothes.org/news/2013/05/24/background-rabrought to you byna-plaza-ta... CORE provided by DigitalCommons@ILR Home News Get involved Safety Living Wage Behind The Scenes Issues Resources About us Share in WhatsApp An overview of the current status of brands and their compensation for the victims. Tazreen The total amount of long-term compensation for the injured and deceased workers at Tazreen is calculated to be 5.7 million USD. The brands are requested to collectively pay 45% of this amount, while other stakeholders including the Bangladeshi government, Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) and the employer are called upon to pay the remaining 55%. In addition, medical costs for injured workers need to be paid. On the 15th of April 2013, the companies sourcing from Tazreen were invited by the global union IndustriALL to discuss their contributions to the long-term compensation for the injured and dead Tazreen workers. C&A, KIK and El Corte Ingles attended the meeting, at which the exact amount of contribution from each company was agreed. CCC is currently in dialogue with C&A to agree how their prevous commitment to pay wages and medical costs for the injured workers,provide financial support to the children of the deceased workers and other payments made to families will fit into this scheme. El Corte Ingles and KIK have not yet confirmed that they will pay the amounts of compensation requested. -

Kik Extends Accord for Bangladesh

Press release KiK extends Accord for Bangladesh New imposition of the agreement important step to further improve the production conditions Bönen, 29.6.2017 -The textil discount KiK has signed the new edition of the "Accord" fire protection and building agreement in Bangladesh. The Westphalian company is therefore one of the first signatories to the new agreement, which will enter into force on 31 May 2018. The aim of the "Bangladesh Accord on Building and Fire Safety" is to continue the measures to improve the protection of buildings and fire in the textile factories of the country after the collapse of Rana Plaza. The signatories to the agreement have undertaken to report their supplier factories to the Accord and to have these factories examined by experts for building safety, fire safety and electrical safety. The shortcomings documented in these inspections are eliminated by the factory owners, in cooperation with the Accord, and the textile companies support these measures financially. Since May 2013 all factories notified to the Accord in 1655 have been inspected, 77% of the identified safety deficiencies have been remedied. "A lot has been achieved in the last five years. But we are not yet on target. The security of textile factories in Bangladesh has improved thanks to the support of the textile companies. However, it is important for the safety of the employees to remain on the ball and to ensure that the outstanding deficiencies are eliminated, "said Patrick Zahn, CEO of KiK. Accord has proven its worth The Accord agreement, which has been concluded in 2013, expires on a five-year term at the end of May 2018. -

Engaging Sustainability Stakeholders

ENGAGING SUSTAINABILITY STAKEHOLDERS LESSONS FROM THE BANGLADESH RANA PLAZA COLLAPSE By IMD Professor Francisco Szekely, with Zahir Dossa, Ph.D. IMD Chemin de Bellerive 23 PO Box 915, CH-1001 Lausanne Switzerland Tel: +41 21 618 01 11 Fax: +41 21 618 07 07 [email protected] www.imd.org Copyright © 2006-2015 IMD - International Institute for Management Development. All rights, including copyright, pertaining to the content of this website/publication/document are owned or controlled for these purposes by IMD, except when expressly stated otherwise. None of the materials provided on/in this website/publication/document may be used, reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or the use of any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from IMD. To request such permission and for further inquiries, please contact IMD at [email protected]. Where it is stated that copyright to any part of the IMD website/publication/document is held by a third party, requests for permission to copy, modify, translate, publish or otherwise make available such part must be addressed directly to the third party concerned. ENGAGING SUSTAINABILITY STAKEHOLDERS | Lessons from the Bangladesh Rana Plaza collapse Sustainable organizations are those that positively impact all stakeholder groups. Richard Freeman formalized the notion of stakeholders in 1984 in an attempt to extend the bounds of responsibility that firms had to society, defining stakeholders as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the firm’s objectives”. -

KIK Is Not Nr.1 in Prices

KIK is not Nr.1 in prices The Hungarian Competition Authority (hereinafter the GVH) has imposed a fine of HUF 1 million (approx. EUR 3700) on KIK who failed to prove his allegations claiming that he was number one in prices on the market. Due to the perception that KIK had been promoting itself in leaflets with the slogan “Number one in prices ∗” and also with the slogan “They all buy here at the Number one ∗” the GVH has launched an investigation. Additionally, the following allegation appeared under the sign ∗ in the leaflets concerning the period from 25 February 2009: “According to TNS Infratest led by KIK in December 2007, KIK was chosen by 76% of the consumers in Germany and 85% of the consumers in Austria”. Furthermore, the following allegation appeared in the leaflets concerning the period from 4 March 2009: “According to the TNS Infratest led by KIK in December 2008, KIK was chosen by 80,5% of the consumers in Germany and 83% of the consumers in Austria”. KIK Textile- and Non-Food Ltd. is interested in retail trade of textile and manufactured goods. It is controlled by KIK Textilien und Non-Food GmbH that possesses a widespread network of stores in many European countries. After its entry to the market in 2008, it opened a huge number of stores in Hungary; their number reached 32 in September 2009. Between the period of 25 February 2009 and 2 June 2009, usually in every two weeks, KIK promoted its products and stores in its own leaflets and in flyers and in the case of opening new stores in newspaper advertisements too. -

Transition Towards Socially Sustainable Behavior? an Analysis of the Garment Sector

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bodenheimer, Miriam Working Paper Transition towards socially sustainable behavior? An analysis of the garment sector Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation, No. S07/2018 Provided in Cooperation with: Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI Suggested Citation: Bodenheimer, Miriam (2018) : Transition towards socially sustainable behavior? An analysis of the garment sector, Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation, No. S07/2018, Fraunhofer-Institut für System- und Innovationsforschung ISI, Karlsruhe, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0011-n-4943482 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/178227 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation No.