Interim Guidance on the Preparation of Demonstrations in Support Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

10-310 Coastal Waters Forecast

NWSI 10-310 JUNE 18, 2019 Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-310 JUNE 18, 2019 Operations and Services Marine, Tropical, and Tsunami Services Branch, NWSPD 10-3 COASTAL WATERS FORECAST NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: AFS26 (W. Presnell) Certified by: AFS2 (A. Allen) Type of Issuance: Routine SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This instruction supersedes NWSI 10-310, Coastal Waters Forecast, dated April 18, 2017. The following revisions were made to this directive: 1. Updated examples to show use of mixed case. 2. Adjusted wording to reflect consolidation of Small Craft Advisories into one headline. 3. In section 2.2.3, removed the phrase “but no earlier than 1 hour before this issuance time.” 4. In section 2.3.5 b1, edited first sentence to read “When a tropical cyclone warning is in effect, the warning headline should supersede all other headlines in the area covered by the tropical cyclone warning.” 5. Removed Note indicating an exception for Alaska Region (top of page 8) 6. In section 2.3.8, added wording that knots should be the unit used to represent wind speed and the term “knot(s)” or “kt” is acceptable in representing wind speed. Also, removed any use of “kts” for knots and used “knot” in body and used “kt” to indicate knots in examples. 7. In section 2.3.8c, indicated that “visibility” should be spelled out and not abbreviated. 8. In section 2.4, added that NWSI 10-1701 has information on character line and total character limitations. -

Inclement Weather Guidelines for Outdoor Events

INCLEMENT WEATHER GUIDELINES FOR OUTDOOR EVENTS “Inclement weather” is a generic term often used to describe weather conditions that are either unsafe or undesirable for outdoor events. Inclement weather can come in many different forms, as outlined below. This guideline is intended to be used as a tool to help you identify when forecasted or actual weather conditions require cancelling or postponing an event. NOTE: This checklist addresses only the most unsafe weather conditions. Your own event guidelines may dictate actions for other weather conditions that may be undesirable (e.g. rainy, too warm, too cold). Should any of the following triggers occur or become forecasted for the time of the event, the event should be cancelled or, when appropriate, temporarily postponed for safety reasons. Temporarily postponing an event means just waiting a few minutes until the immediate hazard passes, if your schedule allows. When in doubt about what to do, consult with FSU Emergency Management for decision support. ADVANCED NOTICE TRIGGER TO CANCEL EVENT: TRIGGER TO TEMPORARILY POSTPONE TIMEFRAME EVENT: 0 ‐ 48 Hours [ ] Hurricane or Tropical Storm Watch [ ] Winter Storm Watch 0 ‐ 24 Hours [ ] Heat Advisory or Excessive Heat Watch [ ] High Wind Watch [ ] Winter Weather Advisory [ ] Wind Chill Advisory 0 ‐ 12 Hours [ ] Tornado Watch [ ] Severe Thunderstorm Watch [ ] Flash Flood Watch [ ] Excessive Heat Warning [ ] Wind Advisory During Event [ ] Observed Heat Index in excess of 108’F. [ ] FSU ALERT issued for Tornado Warning, Severe Thunderstorm Warning, Flash Flood Warning or [ ] Observed Wind Chill less than 0’F. Lightning Warning. [ ] Observed winds in excess of 35 miles per hour. [ ] Significant Weather Advisory (no FSU ALERT). -

Warning Uses Definition of Terms

Warning Uses Convective Weather Flooding Winter Weather Non-Precipitation Tornado Watch Flash Flood Watch Blizzard Warning Tornado Warning Flash Flood Warning Winter Storm Watch Severe Thunderstorm Watch Flood Watch Winter Storm Warning High Wind Warning Severe Thunderstorm Warning Flood Warning Snow Advisory Small Stream Flood Freezing Rain Advisory High Wind Advisory Advisory Ice Storm Warning Winter Weather Advisory Definition of Terms Term Definition Winter Weather There is a good chance of a major winter storm developing in the next several days. Outlook Winter Storm Watch There is a greater than 50% chance of a major winter storm in the next several days Winter Storm Any combination of winter weather including snow, sleet, or blowing snow. The Warning snow amount must meet a minimum accumulation amount which varies by location. Blizzard Warning Falling and/or blowing snow frequently reducing visibility to less than 1/4 mile AND sustained winds or frequent gusts greater than 35 mph will last for at least 3 hours. Ice Storm Warning Freezing rain/drizzle is occurring with a significant accumulation of ice (more than 1/4 inch) or accumulation of 1/2 inch of sleet. Wind Chill Warning Wind chill temperature less than or equal to -20 and wind greater than or equal to 10 mph. Winter Weather Any combination of winter weather such as snow, blowing snow, sleet, etc. where Advisory the snow amount is a hazard but does not meet Winter Storm Warning criteria above. Freezing Light freezing rain or drizzle with little accumulation. Rain/Drizzle Advisory . -

SEVERE WEATHER the Weather in North Texas Can Be Brutal

SEVERE WEATHER The weather in North Texas can be brutal. The weather is among one of the biggest risks we face at UNT. With this in mind, we want to make sure you fully understand the weather risks we face. Severe weather hazards most common in North Texas include the following: Tornadoes Severe Thunderstorms High Winds Flooding Lightning TORNADOES A tornado is a rapidly rotating column of air that is connected to a cloud and making contact with the ground. Tornadoes can be incredibly destructive, with wind speeds in excess of 200 mph possible. Tornadoes are generally associated with the spring months, but tornadoes can also happen any time of year in North Texas. TORNADO WATCH A tornado watch means that conditions are favorable for tornadoes to form. If the National Weather Service issues a tornado watch, remain alert and monitor the weather in the event of announcements. TORNADO WARNING A Tornado Warning means a tornado has been sighted or radar indicates rotation in the clouds. If the National Weather Service issues a tornado warning for Denton County, take the following actions: 1. Proceed to your designated shelter area (which should be an interior room without windows on the lowest level of the building) informing all individuals along your route to take shelter in a designated shelter location 2. Move away from windows, doors, and exterior walls 3. Get under a piece of furniture, if safely possible 4. Monitor the National Weather Service website and social media to determine when the warning has ended 5. Do not leave your shelter until you receive an Eagle Alert explaining that the warning has ended If you are in a car or outdoors during a Tornado Warning and cannot get to a building, cover your head and neck with your arms and cover your body with a coat or blanket, if possible. -

Seamanship by Vincent Pica, Chief of Staff, First District, Southern Region (D1SR), U.S

Seamanship by Vincent Pica, Chief of Staff, First District, Southern Region (D1SR), U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Weather - The Small Craft Advisory - That Means You! With Super Storm Sandy gone but hardly forgot- contiguous land area is home to more than half of its ten, let’s start a weather series. This one will focus on population, action was taken. On June 1, 2007, the US Gale Warning the oft-heard but equally-oft-poorly understood news- Coast Guard re-established the program. From their Gale warnings are issued when winds within 39 - flash that is heard by those that go down to the sea in press release of May 30, 2007, they said, “The re-es- 54 mph (34 - 47 knots) are expected within 24 hours, or ships… The Small Craft Advisory. This column is about tablishment of this program, discontinued by the Na- frequent gusts between 35 knots and 49 knots are ex- that. tional Weather Service in 1989, re-enforces the Coast pected. Gale warnings may precede or accompany a Guard's role as lifesavers and visually communicates hurricane watch. Small Craft Advisory that citizens should take personal responsibility for in- Despite conventional wisdom, the US Coast dividual safety in the face of an approaching storm.” Storm Warnings (wind over water) Guard does not issue Small Craft Advisory warnings. Storm warnings are issued when winds within the They are issued by NOAA’s National Hurricane Cen- range of 55 - 73 mph (48 - 68 knots) are expected within ter. What constitutes the threshold for an advisory? It is The signal flag ( or lights at 24 hours. -

Spearfish Fire Department Policies and Procedures

SPEARFISH FIRE DEPARTMENT POLICIES AND PROCEDURES Page 1 of 5 Volume: Operation Section: 20.00 Number: 20.09 Subject: Weather Watches, Warnings, Advisory’s and Spotter Activation Date Issued: 8 August 2019 Originator: Assistant Chief R. Mathis Rescinds: 28 March 2017 Approval: Assistant Chief R. Mathis I. Purpose This procedure provides guidance for safety and general procedures when responding to Weather Spotter activations. II. SCOPE This policy applies to all personnel. III. DEFINITIONS Winter Storm Watch A Winter Storm Watch is issued when there is the potential for significant and hazardous winter weather within 48 hours. It does not mean that significant and hazardous winter weather will occur...it only means it is possible. Significant and hazardous winter weather is defined as a combination of: 1) 5 inches or more of snow/sleet within a 12-hour period or 7 inches or more of snow/sleet within a 24-hour period AND/OR 2) Enough ice accumulation to cause damage to trees or powerlines AND/OR 3) a life threatening or damaging combination of snow and/or ice accumulation with wind. Blizzard Warning A Blizzard Warning means that the following conditions are occurring or expected within the next 12 to 18 hours. 1) Snow and/or blowing snow reducing visibility to 1/4 mile or less for 3 hours or longer AND 2) Sustained winds of 35 mph or greater or frequent gusts to 35 mph or greater. There is no temperature requirement that must be met to achieve blizzard conditions. Winter Storm Warning A Winter Storm Warning is issued when a significant combination of hazardous winter weather is occurring or imminent. -

Winter Weather Definitions and Terms

Definitions of Winter Weather Terms used by the National Weather Service As winter approaches, you should understand winter weather terms and be aware of winter weather hazards. The National Weather Service uses several terms to tell you exactly what kind of weather to expect, please review the terms below to familiarize yourself with them. 1) WINTER STORM OUTLOOK This is a statement issued when there is a chance of a major winter storms from 3 to 5 days in the future. This is meant to assist people with their long range plans. However, since the outlook is issued so far in advance, the accuracy of the prediction may be limited. 2) WINTER STORM WATCH This means there may be hazardous winter weather due to various elements such as heavy snow, sleet, or ice accumulation from freezing rain. In our region, heavy snow means 7 inches or more of accumulation in 24 hours or less. A "WATCH" is a long range prediction. They are issued at least 12 hours before the hazardous winter weather is expected to begin. When the storm becomes imminent, or has a high probability of occurring, the watch will be upgraded to a "WARNING". 3) WINTER STORM WARNING FOR HEAVY SNOW Seven inches or more of snow will fall within a 24 hour period. 4) WINTER STORM WARNING FOR SEVERE ICING Heavy accumulation of ice due to freezing rain will down trees and power lines. Electricity, or telephone communications, may be out for a long period of time. Roads may become impassable for most vehicles. 5) BLIZZARD WARNING This is issued for a combination of strong winds averaging or frequently gusting to, or above, 35 miles an hour and very low visibility due to blowing or falling snow. -

Wind Advisory Is Cancelled

WWUS72 KCHS 220452 NPWCHS URGENT - WEATHER MESSAGE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE CHARLESTON SC 1152 PM EST MON NOV 21 2005 SCZ045-221100- /O.CAN.KCHS.LW.Y.0001.000000T0000Z-051122T2300Z/ /O.NEW.KCHS.WI.Y.0001.051122T0452Z-051122T1500Z/ BERKELEY- INCLUDING THE CITY OF...MONCKS CORNER 1152 PM EST MON NOV 21 2005 ...LAKE WIND ADVISORY IS CANCELLED... ...WIND ADVISORY IN EFFECT UNTIL 10 AM EST TUESDAY... THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE IN CHARLESTON HAS ISSUED A WIND ADVISORY...WHICH IS IN EFFECT UNTIL 10 AM EST TUESDAY. THE LAKE WIND ADVISORY FOR LAKE MOULTRIE HAS BEEN REPLACED WITH A WIND ADVISORY. SOUTHWEST WINDS OF 20 TO 30 MPH WILL BECOME WEST 25 TO 35 MPH ACROSS ALL OF SOUTHERN SOUTH CAROLINA AND SOUTHEAST GEORGIA TONIGHT AS A STRONG UPPER LEVEL STORM SYSTEM CROSSES THE REGION TONIGHT. WIND GUSTS TO 40 TO 45 MPH ARE ALSO POSSIBLE. WINDS OF THIS MAGNITUDE CAN EASILY BREAK LARGE LIMBS OR BLOW LOOSE OUTSIDE OBJECTS AROUND. MOTORISTS...ESPECIALLY THOSE DRIVING HIGH PROFILE VEHICLES... ARE REMAIN ALERT FOR STRONG WINDS THROUGH MID MORNING TUESDAY. WINDS WILL BE PARTICULARLY HIGH ON ELEVATED BRIDGES SUCH AS THE ARTHUR RAVENEL BRIDGE OR THE TALMADGE MEMORIAL BRIDGE. IN ADDITION...WINDS WILL INCREASE TO 25 TO 30 KNOTS WITH GUSTS TO 35 KNOTS ON LAKE MOULTRIE TONIGHT. THE OPEN LAKE WATERS WILL BE EXTREMELY ROUGH AND MARINERS ARE URGED TO REMAIN IN PORT TONIGHT AND TUESDAY. STAY TUNED TO NOAA WEATHER RADIO ALL HAZARDS...TV OR YOUR LOCAL NEWS SOURCE FOR LATER STATEMENTS FROM THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE IN CHARLESTON. $$ GAZ114-115-221100- /O.CAN.KCHS.FZ.A.0002.051123T0500Z-051123T1400Z/ /O.NEW.KCHS.WI.Y.0001.051122T0452Z-051122T1500Z/ TATTNALL-EVANS- INCLUDING THE CITIES OF...REIDSVILLE...CLAXTON 1152 PM EST MON NOV 21 2005 ...FREEZE WATCH IS CANCELLED.. -

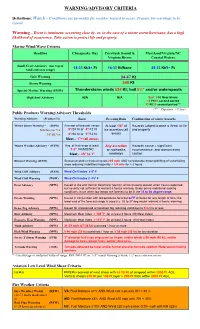

Warning/Advisory Criteria

WARNING/ADVISORY CRITERIA Definitions: Watch – Conditions are favorable for weather hazard to occur. Prepare for warnings to be issued. Warning – Event is imminent, occurring close by, or, in the case of a winter storm/hurricane, has a high likelihood of occurrence. Take action to protect life and property. Marine Wind/Wave Criteria Headline Chesapeake Bay Currituck Sound & Maryland/Virginia/NC Virginia Rivers Coastal Waters Small Craft Advisory (use top of wind and seas range) 18-33 Kt/4+ Ft 18-33 Kt/None 25-33 Kt/5+ Ft Gale Warning 34-47 Kt Storm Warning ≥48 Kt Special Marine Warning (SMW) Thunderstorm winds ≥34 Kt; hail ≥¾” and/or waterspouts High Surf Advisory N/A N/A Surf 8 Ft Near Shore 10 Ft/10 second period 12 Ft/10 second period ** (** = Duration >12 hrs) Public Products Warning/Advisory Thresholds Warning/Advisory (Product ID) Snow Freezing Rain Combination of winter hazards Winter Storm Warning * (WSW) Average of forecast. range: At least 1/4" of Hazards judged to pose a threat to life MD/Interior VA 5"/24 hr or 4"/12 hr ice accretion (all and property NC/SE VA 4"/24 hr or 3"/12 hr areas) Sleet – 1”+ (all areas) Winter Weather Advisory * (WSW) Avg. of fcst range at least: Any accretion Hazards cause A significant 1-2" VA/MD/NC on sidewalks inconvenience, and warrant extra Sleet - .25” to 1” roadways caution Blizzard Warning (WSW) Sustained wind or frequent gusts ≥35 mph AND considerable blowing/drifting of snow/falling snow reducing visibilities frequently < 1/4 mile for > 3 hours Wind Chill Advisory (WSW) Wind Chill Index ≤ 0o F Wind Chill Warning (WSW) Wind Chill Index ≤ -15o F Frost Advisory (NPW) Issued at the end (fall) or beginning (spring) of the growing season when frost is expected, but severity not sufficient to warrant a freeze warning. -

Exceptional Event Demonstration for the August 14, 2015 PM10 Exceedance Due to High Winds

Exceptional Event Demonstration for the August 14, 2015 PM10 Exceedance due to High Winds at Kennewick, Washington November 2017 Publication No. 17-02-015 Template Publication and Contact Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/SummaryPages/1702015.html For more information contact: Air Quality Program P.O. Box 47600 Olympia, WA 98504-7600 Phone: (360) 407-7528 Washington State Department of Ecology – www.ecy.wa.gov o Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Yakima 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Accommodation Requests: To request ADA accommodation including materials in a format for the visually impaired, call Ecology at (360) 407- 6800. Persons with impaired hearing may call Washington Relay Service at 711. Persons with speech disability may call TTY at 877-833-6341. Exceptional Event Demonstration for the August 14, 2015 PM10 Exceedance due to High Winds at Kennewick, Washington by Caroline (Ying) Sun Air Quality Program Washington State Department of Ecology Lacey, Washington Table of Contents Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. i Figures and Tables ............................................................................................................. iii Figures......................................................................................................................... -

NWS Hazard Simplification Project: Major Change Coming to NWS’ Watch, Warning and Advisory System

NWS Hazard Simplification Project: Major Change Coming to NWS’ Watch, Warning and Advisory System Website: https://www.weather.gov/hazardsimplification/ Contact Information: [email protected] 1 The NWS “Watch, Warning and Advisory” System How We Message for Weather & Water Hazards Today ● Watch: Issued when a life- and/or property-threatening event is possible - but not yet certain ● Warning: Issued when a life- and/or property-threatening event is happening or about to happen ● Advisory: Issued when an event less serious than a Warning is happening or about to happen ● Special Weather Statement: Issued when an event less serious (or of shorter duration) than an Advisory is happening or about to happen 2 What is the Planned Major Change? ● All Watches and Warnings will still be issued exactly as they are today, but... ○ All Advisories will be replaced with plain language headlines ➢ (Exception: Small Craft and Tsunami Advisories will become Warnings) ➢ (Also, Center Weather Advisory, space weather and tropical cyclone advisories will remain; these are used to contain descriptive information only) ○ All Special Weather Statements will be converted to plain language headlines ● These changes will not be made prior to 2024 3 Visualizing the Major Change What Will Remain What should I do? - Prepare! What should I do? - Take action! the Same? What Will Change? PLAIN LANGUAGE HEADLINES An event less serious than a Warning is happening ADVISORY Become What should I do? - Exercise caution to avoid impacts. & SPECIAL WEATHER STATEMENT 4 Why Make