Musei Virtuali.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justin Pollard Film & TV Historian / Writer

Justin Pollard Film & TV Historian / Writer Agents Thea Martin [email protected] Credits In Development Production Company Notes OPIUM Tiger Aspect Exec Producer and Historical Consultant UNTITLED PROJECT Mandabach TV Historical Advisor UNTITLED PROJECT STX Historical Advisor 12 CAESARS Green Pavilion Co-Writer Television Production Company Notes VALHALLA MGM Associate Producer and Historical Consultant BROOKLYN HBO Historical Advisor 2018 BORGIA Company of Wolves Research Consultant. BRITANNIA Vertigo Films Historical Consultant United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes WILL Monumental / TNT Historical Consultant THE VIKINGS, Series MGM/ History Channel Associate Producer & Historical 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Consultant. 10 part drama series based on Viking Europe in the 9th century. PAGE EIGHT Carnival Films/ BBC Research Consultant. Film noir thriller starring Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz. Directed by David Hare. QI Quite Interesting Ltd/ Talkback Writer/ Associate Producer. (Series 2 Thames/ BBC1 onward). PEAKY BLINDERS Tiger Aspect/ BBC Research Consultant. Drama series set amongst Birmingham gangs in the early 1920s. THE DRAGONS OF National Geographic Television Writer. MIDDLE EARTH Animated special on the symbolism of the dragon in the medieval Christian world. CAMELOT Starz/ GK-TV Script Consultant. 10 part drama series based on the Morte D’Arthur, starring Joseph Fiennes and Eva Green. THE TUDORS: SERIES Reveille/ Working Title/ TM Research Consultant. I-IV Productions/ Peace Arch Drama series starring Jonathan Rhys Entertainment Group, Inc. for Meyers as Henry VIII. Showtime ALEXANDRIA, Lion Television/ Channel 4 Writer/ Producer. -

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group, Should Be Sent to Jess Obee (Address at End) Or Payments Made at One of the Meetings

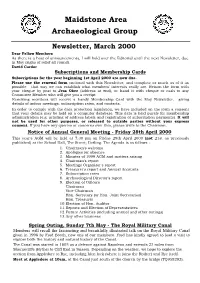

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group Newsletter, March 2000 Dear Fellow Members As there is a host of announcements, I will hold over the Editorial until the next Newsletter, due in May (sighs of relief all round). David Carder Subscriptions and Membership Cards Subscriptions for the year beginning 1st April 2000 are now due. Please use the renewal form enclosed with this Newsletter, and complete as much as of it as possible - that way we can establish what members' interests really are. Return the form with your cheque by post to Jess Obee (address at end), or hand it with cheque or cash to any Committee Member who will give you a receipt. Renewing members will receive a handy Membership Card with the May Newsletter, giving details of indoor meetings, subscription rates, and contacts. In order to comply with the data protection legislation, we have included on the form a consent that your details may be held on a computer database. This data is held purely for membership administration (e.g. printing of address labels and registration of subscription payments). It will not be used for other purposes, or released to outside parties without your express consent. If you have any queries or concerns over this, please write to the Chairman. Notice of Annual General Meeting - Friday 28th April 2000 This year's AGM will be held at 7.30 pm on Friday 28th April 2000 (not 21st as previously published) at the School Hall, The Street, Detling. The Agenda is as follows : 1. Chairman's welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. -

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan FINAL DRAFT Simpson & Brown Architects With Addyman Archaeology August 2012 Contents Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 11 2.1 Objectives of the Conservation Plan ...............................................................................11 2.2 Study Area ..........................................................................................................................11 2.3 Heritage Designations.......................................................................................................13 2.4 Structure of the Report......................................................................................................14 2.5 Adoption & Review...........................................................................................................15 2.6 Other Studies......................................................................................................................15 2.7 Limitations..........................................................................................................................15 2.8 Orientation..........................................................................................................................15 2.9 Project Team .......................................................................................................................15 2.10 Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................16 2.11 Abbreviations and Definitions.........................................................................................16 -

Character Area 22: Railway Archaeological Background

City of York Historic Characterisation Project - 2013, Character area statements Character area 22: Railway Archaeological background Roman Beneath the Cedar Court Hotel architectural fragments including stone capitals and a stone lined well were exposed The archaeological record is dominated by various examinations during building work in 1901(MYO2166, 2162 and 2165). of a substantial cemetery (MYO2010) containing both A conduit and timber lined pit was also located; the pit was inhumations and cremations, principally during construction recorded as c.2.5m below ground level (MYO2167-8). of the current railway station, the Royal Station Hotel and Scarborough Bridge in the late 19th century. In addition, burials, The former railway station located within the walled city structures and occupation evidence were discovered in the area, now West Offices, was subject to several archaeological area towards the riverside. It is believed that the cemetery investigations including five evaluation trenches (EYO4271) in may extend to the south bank of the Ouse (EYO114). More 2009. This evaluation revealed a complex sequence of Roman recently, a watching brief in 1983 at the Railway Station structures c.0.9m+ below ground level, beneath the former revealed disarticulated remains at 1.2m below ground level. station platform some of which are almost certainly associated Contemporary (1876 and quoted in RCHME, Roman York) with the baths complex recorded during the construction of the accounts identified a number of large pits into which had railway station (EYO2580-81). Potential Roman deposits were been ‘thrown’ several bodies in a random manner (EYO418). identified at 1.30m below ground level during a watching brief at Station Rise (EYO431) while a possible Roman courtyard or The location of the character area within the historic core. -

Reports from the Environmental Archaeology Unit, York 2000/04, 51 Pp

Reports from the Environmental Archaeology Unit, York 2000/04, 51 pp. Assessment of biological remains from 41-49 Walmgate York (site code 1999.941) by Cluny Johnstone, John Carrott, Allan Hall, Harry Kenward and Darren Worthy Summary Excavations carried out at 41-49 Walmgate, York, as part of the Time Team Live programme, yielded a total of 34 samples and a single box of bone and shell. Of the samples, 22 (SRS and BS samples) were processed on site and eight GBA samples were processed at the EAU. Analysis was limited to Anglo- Scandinavian and medieval deposits with secure dating evidence. Preservation of biological remains within these deposits was exceptional in a number of ways, particularly the presence of dried (and not rewetted) plant remains and charred insects in association with waterlogged material. The range of plant and insect species was very similar to that observed in Anglo-Scandinavian deposits in other areas of York. The species present were indicative of the interiors of buildings, including moist floor environments and possibly also thatch. Dyeplants and invertebrates associated with wool were present in several deposits, as in many Anglo-Scandinavian deposits from York, suggesting textile processing in the vicinity. The shell and vertebrate assemblages, whilst being well preserved, were too small to provide any useful insights into the economy of the site, other than that they mainly represent food waste. The exceptional preservation of all bioarchaeological remains from this site and the quantity of information gained from such a small scale intervention, has once again highlighted the potential of deposits in this area for yielding a wealth of information on the environment and economy of Anglo- Scandinavian York. -

The Post Hole Issue 15

The Post Hole Issue 15 2 An Interview with Dr Alice Roberts Maximillian Elliot Dr Alice Roberts is one of the country's foremost osteoarchaeologists, as well as being a leading figure in anatomy and anthropology. She has appeared on numerous television programmes, including Time Team and Coast, as well presenting her own documentaries; Digging for Britain, Dr Alice Roberts: Don't Die Young and The Incredible Human Journey which have won her critical acclaim. ME-Was it difficult to break into the world of archaeological media? AR-I fell into archaeology on television almost by accident. I was producing bone reports for archaeological units in the South West, and Time Team asked me if I could write up some reports on skeletons from previous excavations. I produced some reports for them, and was then asked to come on a dig where I'd be looking at bones as they were excavated. It was an Anglo-Saxon burial site in Hampshire, which formed the focus of the Time Team Live dig in 2001. After that, I was invited back to join the team whenever there was a possibility of finding human remains, working with Professor Margaret Cox, which was a great privilege. ME-Your career has encompassed many different disciplines within modern science including, Anatomy, Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology. What made you want to study these particular branches of science? AR-These disciplines might seem very diverse, but the thing which links them all is a fascination with the structure of the human body. Anatomy was my favourite subject when I was an undergraduate studying medicine, but I didn't really expect it to become my career! ME-During your tour of the archaeological sites of Britain in your amazing series, Digging for Britain, what was your favourite site or artefact and why? AR-I loved being able to see the objects and bones in the archive at the Mary Rose Trust. -

Regia Anglorum Media CV

Regia Anglorum Media CV Digging for Britain August 2021 BBC (TX BBC2, scheduled for late 2021) Supply: A demonstration of beer brewing. 2 specialists for a day's shoot at Avalon Marshes Archaeology Park in Somerset. Walks with My Dog July 2017 True North (TX More4, early 2018) Supply: A traders display of an early 10th century Hiberno-Norse trader with trade route specific trade goods, on location in Chester. 4 fully-equipped warriors, 3 civilians, and a trader, all fully costumed. 1 large authentic tent. L'histoire dans la peau October 2016 Groupe PVP, Québec (TX Canadian TV5, November 2017) Supply: Follow 1 re-enactor preparing for the Battle of Hastings 950th anniversary. Interviews with two others on the day. Combat demonstrations. This Week October 2016 BBC2 (TX 6 October 2016) Supply: Two fully armed warriors for half a day's work in Kent. Shed of the Year June 2016 Channel 4 (TX July 2016) Supply: Wychurst Longhall shortlisted for historical shed of the year (and won!). Two fully costumed interviewees. A few extras in the background. Great Army and Alfred work April 2016 World Rights Media Supply: Longhall used as backdrop for this work. 1066: A Year to Conquer England February 2016 BBC (3 × 60 minute episodes) (TX February to March 2017) Supply: Twelve fully equiped warriors and one ship replica on location both at our permanent site in Kent and in Oxfordshire totalling 3 days. Seige of Rochester Castle September 2015 For Medway Council Supply: 70 man-days work over a weekend. Fully armoured warriors and a trebuchet on location at our permanent site in Kent and at Rochester Castle. -

Portable Antiquities Annual Report 1999-2000

Portable Antiquities Annual Report 1999-2000 Contents • Foreword 3 1 Key Points 4 2 Background 6 3 Outreach at a local level: the work of the liaison officers 10 4 Outreach at a national level: the work of the outreach officer and co-ordinator 24 5 The Portable Antiquities Scheme in Wales 27 6 The Portable Antiquities program and the website: www.finds.org.uk 29 7 Portable Antiquities as a source for understanding the historic environment: the Scheme and Sites and Monuments Records 32 8 Portable Antiquities and the study of culture through material 36 9 Figures for finds and finders in 1999-2000 38 10 Conclusions and the future 50 Portable Antiquities Annual Report 1999-2000 Portable Antiquities Annual Report 1999-2000 Foreword I am very pleased to Heritage Lottery Fund, established themselves alongside be able to introduce the original six finds liaison officers who started in autumn the third annual 1997. The present report covers the first full year of all report on the Portable eleven pilot schemes and the post of outreach officer. Antiquities Scheme. Although the schemes cover a wide diversity of regions, I am delighted that they undoubtedly show that there is a need for the services last November the of the finds liaison officers throughout the whole of Scheme received the England and Wales. Spear and Jackson From 1 April this year, the management of the Scheme will Silver Trowel award pass to a consortium of national bodies led by Resource: the for the best initiative Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries. Other in archaeology in the members include English Heritage, the British Museum, country, as well as the National Museums & Galleries of Wales, the Royal the Virgin Holidays Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of award for the Wales, the Association of Local Government Archaeological best-presented Officers, the Council for British Archaeology, the Society of archaeological project, at the British Archaeological Museum Archaeologists and the National Council for Metal Awards ceremony in Edinburgh. -

Canterbury's Archaeology 1976–2016

t s u r T l a ic g o 6 l 1 o 0 e –2 a 6 h 7 c 19 r y A og y ol ur ae rb ch te Ar an ry’s s: C rbu 40year ante C 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 2LU tel: 01227 462062, fax: 01227 784724 email: [email protected] http://www.canterburytrust.co.uk The Canterbury Archaeological Trust is an independent charity formed in 1975 to undertake rescue excavation, research, publication and presentation of the results of its work for the Contents benefit of the public. 40years: Canterbury Archaeological Trust Beginnings ......................................................................................................................... 1 1986–1996 ........................................................................................................................ 5 1996–2006 ........................................................................................................................ 8 2006–2016 ......................................................................................................................12 ......................................................................................19 Further copies of Canterbury’s Archaeology can be Building recording obtained from 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 2LU Environmental archaeology ..........................................................28 © Canterbury Archaeological Trust Limited 2016 Publications ........................................................................................................32 The Ordnance Survey data included in this -

An Irish 'String' Bead in Viking York

58 An Irish ‘String’ Bead in Viking York by Carole Morris any members who are fans of Channel 4's the bead width and shape. Another bead of this type was Marchaeological Time Team programmes may have found at Lagore Crannog in County Meath. Newsletter watched the live broadcasts from York in September 1999 Our York bead is a unique example of a type of string where York Archaeological Trust and the Time Team’s bead almost certainly made in Ireland and although the excavation crew were excavating three sites, one at a beads of this type are characterised by a large number of Medieval and Viking Age site in Walmgate. The star find decorative variations, they have common features which from the whole weekend's excavations was are instantly recognisable and distinguish the polychrome glass bead found in "all them from other string beads made at that medieval poo" in Walmgate to quote different times and in different areas of Patrick Ottoway (2000, 21)! I didn't see North West Europe. These common the programme live as I was away from features are a tripartite construction home, but saw the bead for the first time (plain or decorated body with two end on a video recording a few days later and collars) and a restricted pallette of was amazed (like everyone else) to see colours (always a blue body this beautiful example of a type of bead decorated with blue and white I've been researching for a few years twisted rods and additional opaque Bead Society of Great Britain Bead Society of Great now, since it's quite rare to find white and opaque yellow decorative them on English sites (figs 1 & 2) features such as eyes, trails etc.). -

Table of Membership Figures For

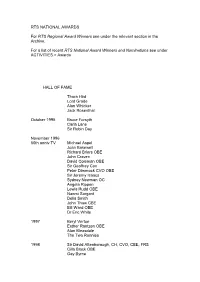

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

David Coleman’S Cv June 2018 Page 1

DAVID COLEMAN’S CV JUNE 2018 PAGE 1 AWARD WINNING PROGRAMMES . BREAKING THE SILENCE LIVE - 2016 TRUENORTH for CHANNEL 4 A live documentary from Manchester Royal Infirmary watching the moment that 8 deaf patients could hear as their cochlear implants were switched on. Simultaneously streamed live on Facebook. [email protected] LEE MACKENZIE LIVE VOICE OVER - NO IN-VISION PRESENTER. WINNER: BEST FACTUAL PROGRAMMME 07973 131348 PROLIFIC NORTH AWARDS ______________________________________________________________ DON’T PANIC 1 & 2 – 2015 - 16 WINGSPAN for BBC 2 I introduced the BBC to Musion for The Truth about Population. Musion is a system for producing floating images for a live audience. The presenter and the audience can see everything during the recording. No post-production trickery. HANS ROSLING’s highly entertaining presentation following on from his acclaimed lecture “THE JOY OF STATS” WINNER: INNOVATIVE JOURNALISM AWARD RTS 2015 ______________________________________________________________ DRUGS LIVE 1 & 2 - 2014 - 15 RENEGADE for CHANNEL 4 2 groundbreaking, scientific programmes the first of which examined the effects MDMA (Ecstasy) and the second, Drugs Live: Cannabis on Trial was a scientific trial looking at the effects on the brain of two different forms of cannabis – ‘skunk’ and ‘hash’. Drugs Live: Cannabis on Trial won an AIB award. Presented by JON SNOW and DR. CHRISTIAN JESSON WINNER: BEST SCIENCE PROGRAMME AIB AWARDS 2015 [ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS] ______________________________________________________________ ANATOMY FOR BEGINNERS FIREFLY for CHANNEL 4 I directed several series of anatomy programmes with Gunther Von Hagens both in the UK and in Germany. The first was The Autopsy filmed with a police presence in East London.