The Communicative and Psychological Causal Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlanta Braves (45-52) Vs

Atlanta Braves (45-52) vs. St. Louis Cardinals (63-34) Game No. 98 July 26, 2015 Busch Stadium St. Louis, Mo. RHP Matt Wisler (4-1, 3.60) vs. RHP Michael Wacha (11-3, 3.20) TODAY’S GAME: The Braves and St. Louis Cardinals play the fi nale of a three-game set and the third of six meetings between the two clubs this season...The Braves and Cardinals wrap up the 2015 campaign with a three-game Braves vs. Cardinals set at Atlanta (Oct. 2-4)...Atlanta trails the Cardinals in the all-time series 890-1037-18, including a 240-273-1 mark 2014 2015 All-Time during the Atlanta era (since 1966)...The Braves also trail 12-19 at Busch Stadium...ROAD TRIPPIN: Last night Overall (since 1900) 2-4 0-1 890-1037-18 Atlanta Era (since ‘66) --- --- 240-273-1 the Braves opened a 10-game road trip to St. Louis (0-2), Baltimore (July 27-29) and Philadelphia (July 30-August 2). at Atlanta 1-2 --- 129-128 SMOLTZ TO BE INDUCTED TODAY: Former Braves pitcher John Smoltz will be inducted into the Na- at Turner Field --- --- 40-24 tional Baseball Hall of Fame today in Cooperstown, NY...Acquired from Detroit by GM Bobby Cox in 1987, Smoltz at St. Louis 1-2 0-1 419-552-11 fashioned his Hall of Fame career by excelling as both a starter and reliever over the span of two decades from 1988 to at Busch Stad. (since ‘06) --- --- 12-19 2008...He is the only pitcher in major league history with 200 or more wins and 150-plus saves...In 14 full seasons as a starter, Smoltz won 14 or more games 10 times...Twice, he led the NL or shared the lead in wins (1996 and 2006), in- nings -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Clemente Quietly Grew in Stature by Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.Com

Clemente quietly grew in stature By Larry Schwartz Special to ESPN.com "It's not just a death, it's a hero's death. A lot of athletes do wonderful things – but they don't die doing it," says former teammate Steve Blass about Roberto Clemente on ESPN Classic's SportsCentury series. Playing in an era dominated by the likes of Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente was usually overlooked by fans when they discussed great players. Not until late in his 18- year career did the public appreciate the many talents of the 12-time All-Star of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Of all Clemente's skills, his best tool was his right arm. From rightfield, he unleashed lasers. He set a record by leading the National League in assists five seasons. He probably would have led even more times, but players learned it wasn't wise to run on Clemente. Combined with his arm, his ability to track down fly balls earned him Gold Gloves the last 12 years of his career. At bat, Clemente seemed uncomfortable, rolling his neck and stretching his back. But it was the pitchers who felt the pain. Standing deep in the box, the right-handed hitter would drive the ball to all fields. After batting above .300 just once in his first five seasons, Clemente came into his own as a hitter. Starting in 1960, he batted above .311 in 12 of his final 13 seasons, and won four batting titles in a seven-year period. Clemente's legacy lives on -- look no farther than the number on Sammy Sosa's back. -

July Birthdays Cow Chips KARE-11 to Feature Area Ballparks Arpi

July 2000 Arpi Continues Bibliography Work KARE-11 to Feature Area Ballparks Rich Arpi continues to prepare Current Baseball Following the All-Star Game on Tuesday, July 11, the Publications, the quarterly newsletter of the SABR KARE-TV (Channel 11) news will have a feature on Bibliography Committee. It contains a list of recently Nicollet and Lexington parks, homes of the Minneapolis published books and magazines on baseball. The news- Millers and St. Paul Saints. The talking heads on the letter is free to all committee members, and all issues segment will include Rich Arpi and your scribe. since 1995 can be viewed on the SABR web page at: http://www.sabr.org/cbp.shtml Chapter Profiles Rich Wolf is hoping to come off the 60-day disabled Cow Chips list after a year-and-a-half of being ill and going through Glenn Gostick was featured in an article on Dick two surgeries last summer. Rich has been a lifelong Cassidy in the Saturday, May 13, 2000 Star Tribune, baseball fan. He was batboy for the St. John’s Newspaper of the Twin Cities. “No one knows and University baseball team, for which his brother played, loves the game more than him,” Cassidy said of Gos. when he was nine. Rich later played high school base- . Roger Godin went to Ottawa for the Society for ball and town ball in Long Prairie. His two great thrills in International Hockey Research convention and made a baseball were touring the Hall of Fame and seeing two presentation on the 1915-16 St. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Saturday, April 18, 2020 * The Boston Globe Fenway Park is ready to play ball, even though we are not Stan Grossfeld The grass is perfect and the old ballpark is squeaky clean — it was scrubbed and disinfected for viral pathogens for three days in March. Spending a few hours at Fenway Park is good for the soul. The ballpark is totally silent. The mound and home plate are covered by tarps and the foul lines aren’t drawn yet, but it feels as if there still could be a game played today. The sun’s warmth reflecting off The Wall feels good. The tug of the past is all around but the future is the great unknown. In Fenway, zoom is still a word to describe a Chris Sale fastball, not a video conferencing app. Old friend Terry Francona and the Cleveland Indians would have been here this weekend and there would’ve been big hugs by the batting cage and the rhythmic crack of bat meeting ball. But now gaining access is nearly impossible and includes health questions and safety precautions and a Fenway security escort. Visitors must wear a respiratory mask, gloves, and practice social distancing, larger than the lead Dave Roberts got on Mariano Rivera in the 2004 ALCS. Carissa Unger of Green City Growers in Somerville is planting organic vegetables for Fenway Farms, located on the rooftop of the park. She is one of the few allowed into the ballpark. The harvest this year all will be donated to a local food pantry. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

Blood Drive Collects Record Amount of Donations

Volume 43 Issue 2 Student Newspaper Of Shaler Area High School November 2016 Bloodby Ceari Robinson drive and Addeline collects Devlin for others this record was a first amount of donationsfirst, the students register on the time experience. computer and answer questions. Shaler Area High School hosted a blood drive “A lot of people will These questions are for the blood Thursday November 3. The Central Blood Bank vis- hype it up but it is really bank only, just to reassure them that its twice a year giving students and teachers an op- not that bad. I would rec- donor’s blood is safe to use. Next, portunity to give blood which in turn is used to save ommend it because you the students move to the interview lives. save three lives every process. This is where the nurse Shaler Area has been holding blood drives for time so why not?” senior will draw a sample of your blood more than 20 years. This year, 153 people signed up Stephen Borgen said. and test it for iron, take your tem- to donate, which equates to potentially saving 500 Central Blood Bank perature and take your blood pres- lives. even offers scholarships sure. If cleared, a student moves to “I think the blood drive is going great, we are on to students who partici- the cot to donate. This part alone track to collect the most units we have ever gotten”, pate. For every donation, only takes about 10-15 minutes and Natalia Petrulli, the Central Blood Bank Account the school earns points then you get to sit and eat snacks. -

First Look at the Checklist

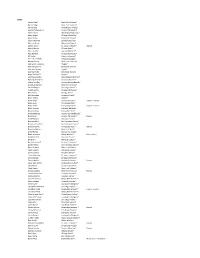

BASE Aaron Hicks New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® Adam Eaton Washington Nationals® Adam Engel Chicago White Sox® Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adam Ottavino Colorado Rockies™ Addison Reed Minnesota Twins® Adolis Garcia St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® Alex Colome Seattle Mariners™ Alex Gordon Kansas City Royals® All Smiles American League™ AL™ West Studs American League™ Always Sonny New York Yankees® Andrelton Simmons Angels® Andrew Cashner Baltimore Orioles® Andrew Heaney Angels® Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® Angel Stadium™ Angels® Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® Antonio Senzatela Colorado Rockies™ Archie Bradley Arizona Diamondbacks® Aroldis Chapman New York Yankees® Austin Hedges San Diego Padres™ Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® Billy Hamilton Cincinnati Reds® Blake Parker Angels® Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Treinen Oakland Athletics™ Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® Brad Boxberger Arizona Diamondbacks® Brad Keller Kansas City Royals® Rookie Brad Peacock Houston Astros® Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® Brandon Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie Brandon Nimmo New York Mets® Brett Phillips kansas City Royals® Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® Future Stars Brian McCann Houston Astros® Bring It In National League™ Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® Buster Posey San Francisco -

Guerrillas Release Hostages

COMP JH5 LISRAST OF 3 BOCA HAiw.T * FLA 33432 Off 5.68 Church news 1:30 Dow-Jones Ready for Sunday STOCKS, Page 8 BOCA RATON NEWS On Page 6 Vol. 15, No. 134 Friday, June 12, 1970 14 Pages 10 Cents 'You have to be there to know' who were killed and wounded by mines WASHINGTON (UPI) —To the Capt. Medina talks about the 'massacre' charge and bobby traps. This type of thing you stocky man, wearing his life's work in cannot fight back. I believe it's the rows of campaign ribbons, it seems a most demoralizing thing the individual simple truth: If you've never been specific issues Medina had talked helicopter pilot had dropped smoke to Medina, who commanded Company soldier must face. He doesn't know if there, you can't judge those who were. about earlier. marka Viet Cong body so U.S. troops C, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, spoke the next step he's going to take may be The soldier is Ernest L. Medina, 33, First, was what happened at My Lai, could search for weapons. freely of his outfit and of the fatigue his last." captain of infantry, accused of mur- as President Nixon said it appeared to Medina: "As I approached, I noticed and frustrations he and his men en- dering "not less" than 175 persons at be, a massacre? it was a woman. I looked in the area countered. Medina had some firm ideas about My Lai 4 in South Vietnam on March Medina: "As I have stated on and noticed there was no weapon. -

04-21-2012 A's Post Game Notes

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Post Game Notes Oakland Athletics Baseball Company 7000 Coliseum Way Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 Public Relations Facsimile 510-562-1633 www.oaklandathletics.com Cleveland Indians (8-5) at Oakland Athletics (7-9) Saturday, April 21, 2012 Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E LOB Cleveland 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 3 0 5 14 0 11 Oakland 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 8 0 8 W — Gomez (1-0) L — McCarthy (0-3) SV — Perez (6) OAKLAND NOTES The Oakland Athletics have lost two straight after a season-high three-game winning streak…are 0-2 on this six-game homestand against Cleveland (0-2) and Chicago (three games). The A’s were held to just one run and have scored just 47 runs for the season, which is the fewest in Oakland history over the first 16 games (previous 50 in 1970). The A’s stole a season-high three bases and have an American League leading 14 for the season. Brandon McCarthy has received three runs of support or fewer in all five of his starts this year…has a 3.38 ERA but is 0-3. Yoenis Cespedes (0 for 2, bb) has reached base safely via hit or walk in 14 of his 15 games. Pedro Figueroa made his Major League debut by pitching a scoreless ninth inning (1 bb). The A’s had 18 attendees for the 1972 World Series Reunion including: Vida Blue, Bert Campaneris, Tim Cullen, Dave Duncan, Rollie Fingers, Dick Green, Dave Hamilton, Mike Hegan, Ken Holtzman, Joe Horlen, Helen Hunter (wife of Jim Hunter), Darold Knowles, Ted Kubiak, Bob Locker, Irv Noren, Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace and Kathy Williams (daughter of Dick Williams).