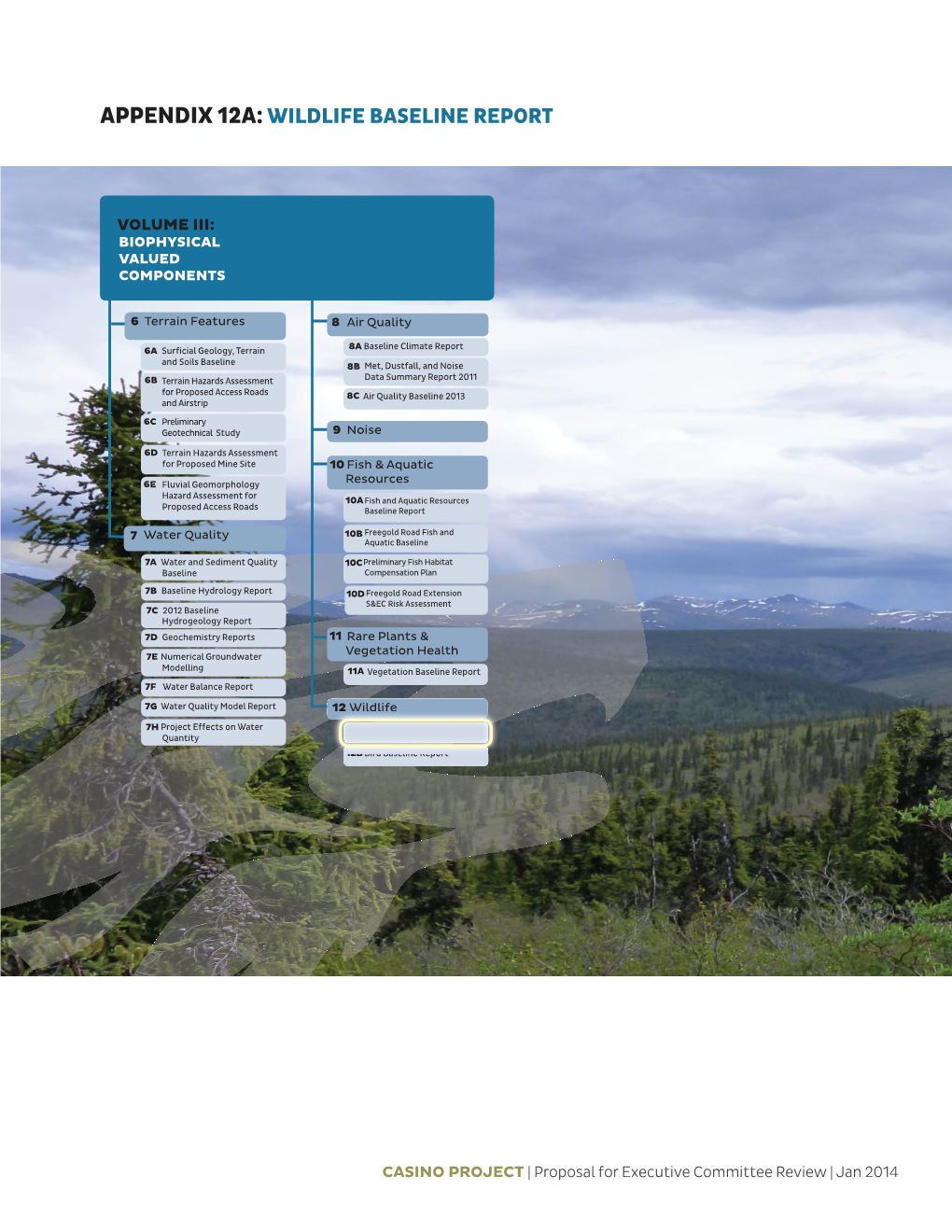

12A Wildlife Baseline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Nations & Transboundary Claimants

How to Contact Yukon First Nations & Transboundary Claimants Carcross/Tagish First Nation Kaska Ta’an Kwäch’än Council Box 130 Liard First Nation 117 Industrial Road Carcross, YT Y0B 1B0 Box 328 Whitehorse, YT Y1A 2T8 Location: Turn off Klondike Hwy at Watson Lake, YT Y0A 1C0 Tel (867) 668-3613 south end of bridge Location: On Campbell Hwy, across Fax (867) 667-4295 Tel (867) 821-4251 from high school/Yukon College Tel (867) 821-8216 – Lands Admin. Tel (867) 536-5200 – Administration Teslin Tlingit Council Fax (867) 821-4802 Tel (867) 536-2912 – Land Claims Fax (867) 536-2109 Box 133 Teslin, YT Y0A 1B0 Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Ross River Dena Council Location: On southwest side of General Delivery Alaska Highway Box 5309 Ross River, YT Y0B 1S0 Tel (867) 390-2532 – Administration Haines Junction, YT Y0B 1L0 Location: Near Dena General Store Tel (867) 390-2005 – Lands Location: Turn off Alaska Hwy, Tel (867) 969-2278 – Administration Fax (867) 390-2204 across from FasGas, follow signs Tel (867) 969-2832 – Economic Tel (867) 634-2288 – Administration Development Fax (867) 969-2405 Tetlit Gwich’in Council Tel (867) 634-4211 – Ren. Res. Mgr. Fax (867) 634-2108 Box 30 Little Salmon/Carmacks Fort MacPherson, NWT X0E 0J0 In Whitehorse: First Nation Location: On Tetlit Gwichin Road #100 – 304 Jarvis Street Tel (867) 952-2330 Whitehorse, YT Y1A 2H2 Box 135 Fax (867) 952-2212 Tel (867) 668-3627 Carmacks, YT Y0B 1C0 Fax (867) 667-6202 Location: Turn west off Klondike Hwy at north end of bridge to admin bldg Tr’ondëk Hwëch'in Inuvialuit Regional Corp. -

Yukon and Alaska Circle Tour Introduce Yourself to Northern Culture and History in Whitehorse, Then Relive Dawson City’S Gold Rush by Panning for Gold

© Government of Yukon Yukon and Alaska Circle Tour Introduce yourself to northern culture and history in Whitehorse, then relive Dawson City’s gold rush by panning for gold. Learn about First Nations culture from Aboriginal people. Drive a highway at the roof of the world, paddle and raft remote rivers, hike, catch a summer festival or relax in hot springs under the Midnight Sun. Approx. distance = ALASKA 1 Whitehorse 9 Boundary 9 1073 mi (1728 km) 10 (Alaska) 8 YUKON 2 Braeburn 11-12 days 11 10 Chicken (Alaska) 3 Carmacks 12 7 11 4 Pelly Crossing Tok (Alaska) 5 6 4 12 Beaver Creek 5 Stewart Crossing 13 3 13 Destruction Bay 2 6 Mayo 14 NORTHWEST 14 Haines Junction 7 Keno 1 TERRITORIES Whitehorse 1 Whitehorse 8 Dawson City NUNAVUT Start: DAY 1-2 – Whitehorse Yukon International Storytelling Festival Northern Lights Tours Celebrate the North’s rich storytelling tradition under the Midnight Mid-August through April, experience brilliant displays of the Aurora Sun annually. Listen to performers from circumpolar countries and Borealis. Several tour operators offer excursions to see these beyond. In October. celestial night shows when multi-colored streamers of light shimmer overhead while you watch from a secluded log cabin or while MacBride Museum of Yukon History soaking in natural mineral waters at Takhini Hot Springs pools. Learn about the Klondike gold rush and the development of the Canadian north. Check out displays of First Nations traditions, the Muktuk Adventures legacy of Canadian poet Robert Service, and the Mounted Police Get to know sled dogs and puppies at a kennel and B&B. -

CHON-FM Whitehorse and Its Transmitters – Licence Renewal

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2015-278 PDF version Reference: 2015-153 Ottawa, 23 June 2015 Northern Native Broadcasting, Yukon Whitehorse, Yukon and various locations in British Columbia, Northwest Territories and Yukon Application 2014-0868-3, received 29 August 2014 CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters – Licence renewal The Commission renews the broadcasting licence for the Type B Native radio station CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2021. This shortened licence term will allow for an earlier review of the licensee’s compliance with the regulatory requirements. Introduction 1. Northern Native Broadcasting, Yukon filed an application to renew the broadcasting licence for the Type B Native radio station CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters CHCK-FM Carmacks, CHHJ-FM Haines Junction, CHOL-FM Old Crow, CHON-FM-2 Takhini River Subdivision, CHON-FM-3 Johnson’s Crossing, CHPE-FM Pelly Crossing, CHTE-FM Teslin, VF2024 Klukshu, VF2027 Watson Lake, VF2028 Mayo, VF2035 Ross River, VF2038 Upper Liard, VF2039 Carcross, VF2049 Dawson City, VF2125 Takhini River Subdivision, VF2126 Keno City, VF2127 Stewart Crossing, VF2128 Tagish, VF2147 Destruction Bay, VF2148 Whitehorse (Mayo Road Subdivision), VF2311 Lower Post and VF2414 Faro, Yukon; VF2306 Atlin and VF2353 Good Hope Lake, British Columbia; VF2354 Aklavik, and VF2498 Tsiigehtchic (Arctic Red River), Northwest Territories, which expires on 31 August 2015. The Commission did not receive any interventions regarding this application. Non-compliance 2. Section 9(2) of the Radio Regulations, 1986 (the Regulations) requires licensees to file an annual return by 30 November of each year for the broadcast year ending the previous 31 August. -

Faro Landscape Hazards

Faro Landscape Hazards Geoscience Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning This publication may be obtained from: Northern Climate ExChange Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College 500 College Drive P.O. Box 2799 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 5K4 867.668.8895 1.800.661.0504 yukoncollege.yk.ca/research Recommended citation: Benkert, B.E., Fortier, D., Lipovsky, P., Lewkowicz, A., Roy, L.-P., de Grandpré, I., Grandmont, K., Turner, D., Laxton, S., and Moote, K., 2015. Faro Landscape Hazards: Geoscience Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning. Northern Climate ExChange, Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College. 130 p. and 2 maps. Front cover photograph: Aerial view of Faro looking southeast towards the Pelly River. Photo credit: archbould.com Disclaimer: The report including any associated maps, tables and figures (the “Information”) convey general observations only. The Information is based on an interpretation and extrapolation of discrete data points and is not necessarily indicative of actual conditions at any location. The Information cannot be used or relied upon for design or construction at any location without first conducting site-specific geotechnical investigations by a qualified geotechnical engineer to determine the actual conditions at a specific location (“Site-Specific Investigations”). The Information should only be used or relied upon as a guide to compare locations under consideration for such Site-Specific Investigations. Use of or reli- ance upon the Information for any other purpose is solely at the user’s own risk. Yukon College and the individual authors and contributors to the Information accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from the use of the Information. -

Bill S-6, Yukon and Nunavut Regulatory Improvement Act Pétion : Projet De Loi S-6, Loi Sur L’Amélioration De La Réglementation Au Yukon Et Au Nunavut

Petition: Bill S-6, Yukon and Nunavut Regulatory Improvement Act Pétion : Projet de loi S-6, Loi sur l’amélioration de la réglementation au Yukon et au Nunavut Last Name - Nom de famille First Name - Prénom City - Ville Aidole Suzanne Carcross Smith Howard Aspen Place Smarch Mary Jane Beaver Creek Ballegooyen Kati Burnash Landing Atlin Sheri Burwash Landing Dickson Robert Burwash Landing Dickson Alanna Burwash Landing Hicks Adam Burwash Landing McCready Colum Burwash Landing Moreno-Herrera Natalia Burwash Landing Pope Geraldine Burwash Landing Turner Jamie Calrgary Barette Christina Carcross Barr Jona Carcross Barr Kevin Carcross Beaffie Cynthia Carcross Beattie Shirley Carcross Ginc Bessie Carcross Huebschwerler Cindy Carcross Huebschwerler Margaret Carcross James Albert Carcross Linnemoller Kaitlyn Carcross Wally Anne Carcross Wetin Maryanne Carcross Billy Benson Carmacks Ajoub Natasha Dawson Anderson Allison Dawson Beaumont Jody Dawson Bibber Clara Van Dawson Bolt Glenda Dawson Burvey Marta Dawson Clarke Chris Dawson Dites Katnna Dawson Enderslev Erik V. Dawson Every Kylie Van Dawson Hallbom Alexander Dawson Joseph-Reav Angie Dawson Kormendy Shawna Dawson Morberg Julia Dawson Nagano Debbie Dawson Nagano Simon Dawson Taylor Tim Dawson Thom Adam Dawson Vigliotti Daniel J. Dawson MacLeod Chris Dawson City Djabii Yasmine Faro Petition: Bill S-6, Yukon and Nunavut Regulatory Improvement Act Pétion : Projet de loi S-6, Loi sur l’amélioration de la réglementation au Yukon et au Nunavut Hannah Doug Faro Alexie Dorothy Fort McPherson Brown Judy -

Services and Driving Information Yukon Checkpoints

Services and Driving Information Yukon Checkpoints Dawson City - Population: 1,410 Teams have a mandatory 36-hour layover, and are likely to arrive in Dawson City between February 5 and 7. Tuesday and Wednesday are the best days to see teams arriving. Teams are likely to leave Dawson City after the mandatory 36-hour layover predicted between February 6 and 10. The Dawson City Mandatory Layover is also “Yukon Quest Time” in the Klondike capital! With teams’ arrivals spread out over a day or two, coupled with each team’s 36-hour stay, the entire City of Dawson City goes dog-crazy for five days! DRIVING Dawson City is approximately six hours from downtown Whitehorse, but can take much longer in bad weather. Checkpoint Services Purchase food and concessions during extended hours. No free accommodations available. All volunteers and visitors need to book their own accommodations in the local hotels. Events/Activities Dog Park Campground - visitors can walk to the Dog Park Campground across the river to see where the dog teams are camped for their mandatory layover. Visitors are welcome in the campground, but cannot enter individual campsites or disturb any of the dog teams. Their uninterrupted rest is essential during this time. Vehicles are not allowed in the dog park. Volunteers at the Dawson City checkpoint are invited to join us at our Yukon Quest Appreciation Night. COMMUNITY SERVICES There are many restaurants in town, and they are easily accessible on foot. Be sure to book your accommodations as soon as possible – hotels fill up fast! Other available amenities include: gas stations, souvenir shops, a drug store, Canada Post, etc. -

14 Day Explore Yukon by Camper Van

Tour Code 14YCV 14 Day Explore Yukon by Camper Van 14 days Created on: 26 Sep, 2021 Day 1: Arrive in Whitehorse The capital of the Yukon, Whitehorse, offers a charming inside to the history of the North. We suggest a trip to the Visitor Centre to learn about the different regions of the Yukon and pick up some maps. Then a walk to the riverfront Kwanlin Dun Cultural Centre. This award-winning building celebrates the heritage, culture and contemporary way of life of Yukon's Kwanlin Dun First Nations people. Whitehorse also has great shops, galleries and museums that are open all year. We suggest a tour through the MacBride Museum and a stroll down Main Street to spend time with the locals in the lively cafés. Keep an eye out for locally sourced food and drink products, you will be surprised at the culinary scene in this northern town. The long evening is set aside to explore the capital of the Yukon on foot. While the northern lights occur year-round, summer's near-constant daylight makes seeing them next to impossible. In late summer and early autumn however, clear, dark nights lend themselves to stunning displays. From late August onwards, we suggest you locally book for a Northern Lights viewing at the Aurora Centre in the comfort of insulated yurts with a steaming hot drink. Overnight: Whitehorse Day 2: Half Day Guided Canoe Trip To get immersed in the ?northern spirit? there is nothing better than to experience the Yukon River first-hand. Deeply connected with every aspect of this Territory?s history and culture, a half day float down the river will give you valuable insights. -

Ross River Landscape Hazards

Ross River Landscape Hazards Geoscience Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning This publication may be obtained from: Northern Climate ExChange Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College 500 College Drive P.O. Box 2799 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 5K4 867.668.8895 1.800.661.0504 yukoncollege.yk.ca/research Recommended citation: Benkert, B.E., Fortier, D., Lipovsky, P., Lewkowicz, A., de Grandpré, I., Grandmont, K., Turner, D., Laxton, S., Moote, K., and Roy, L.-P., 2015. Ross River Landscape Hazards: Geoscience Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning. Northern Climate ExChange, Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College. 116 p. and 2 maps. Front cover photograph: Aerial view of the community of Ross River looking southeast. Photo credit: Yukon Geological Survey Disclaimer: The report including any associated maps, tables and figures (the “Information”) convey general observations only. The Information is based on an interpretation and extrapolation of discrete data points and is not necessarily indicative of actual conditions at any location. The Information cannot be used or relied upon for design or construction at any location without first conducting site-specific geotechnical investigations by a qualified geotechnical engineer to determine the actual conditions at a specific location (“Site-Specific Investigations”). The Information should only be used or relied upon asa guide to compare locations under consideration for such Site-Specific Investigations. Use of or reliance upon the Information for any other purpose is solely at the user’s own risk. Yukon College and the individual authors and contributors to the Information accept no liability for any loss or damage arising from the use of the Information. -

Appendix 13A:Socio-Economic Baseline Report

APPENDIX 13A: SOCIO-ECONOMIC BASELINE REPORT Volume I: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Volume II: Volume III: Volume IV: Volume V: Project BIoPhysIcal socIoeconomIc addItIonal IntroductIon Valued Valued yesa & oVerVIew comPonents comPonents reQuIrements 1 Introduction 6 Terrain Features 13 Employment 20 Effects of the and Income Environment on 6a Surficial Geology, Terrain the Project 2 First Nations and Soils Baseline 14 Employability and Community 20a Climate Change Report 6B Terrain Hazards Assessment Consultation for Proposed Access Roads and Airstrip 15 Economic 21 Accidents and 2a Consultation Log 6c Preliminary Development Malfunctions Geotechnical Study and Business 2B Consultation Materials 21a Regulatory Setting 6d Terrain Hazards Assessment Sector 3 Project Location for Proposed Mine Site 21BRisk Register 16 Community 6e Fluvial Geomorphology Hazard Assessment for Vitality Proposed Access Roads 22 Conceptual 4 Project Description Environmental 17 Community Management Plans 7 Water Quality 4a Conceptual Closure Infrastructure and ReclamationPlan and Services Road Use Plan 7a Water and Sediment Quality 22a Baseline 4B Freegold Road Report Socio-Economic 13a13a 22B Emergency Baseline Report 7B Baseline Hydrology Report Response Plan 4c Water Management Plan 7c 2012 Baseline Hydrogeology Report 22c Cyanide 18 Cultural Continuity Management Plan 5 Effects Assessment 7d Geochemistry Reports Methodology 7e Numerical Groundwater Modelling 18a Stage 1 Archaeological Monitoring Plans Mitigation 23 5a Project Components and 7F Water Balance Report -

Telling Stories Caring, Sharing, Respect, Teaching Fall/Winter 2018 Volume 14 • Issue 2

Hets Eday Telling Stories www.selkirkfn.com Caring, Sharing, Respect, Teaching Fall/Winter 2018 Volume 14 • Issue 2 PRODUCTS OF OUR NORTHERN TUTCHONE CRAFTERS from the Christmas Sewing Project Nov. 23-Dec. 6, 2018 Chief’s Message .......................2-3 Citizen Development ........ 18-24 Council Highlights ................... 4-6 Lands, Resources Inside SFN News Department Updates ..........8-13 & Heritage ........................ 25-31 Health & Social Programs 14-17 Other News .......................... 35-43 A message from Chief Sharon Nelson Inye dóhúch’i (how are you) hristmas is fast approaching. CThe holiday season offers an opportunity for family and friends to gather and spend time together. During the Christmas holidays, SFN will be delivering various events for children and family-oriented activities from December 26th to January 4th. For your safety, Community Safety Officers will be hired to patrol the community throughout the holidays. In the spirit of the season, Council sends to you and your family best wishes for the holidays and all the best in training strategy, that will take addition to this, workshops were the New Year. into consideration the needs of brought in to provide employees our Citizens, government and the with new skills. It was nice to see Summer and Fall has come and private sector in our Traditional employees interacting with each gone so quickly this year. I hope Territory. This is not the first time a other, learning, and contributing you all had some time to enjoy GA has expressed the importance to the community. This is a good the beauty of our land, the Yukon, of offering training to our Citizens. -

SFN NEWS Spring 2015

VOLUME 11, Issue 1 SFN NEWS Spring 2015 News Hets eday (Telling stories) Northern Tutchone Research Team from SFN: Rachell Tom Tom, Lizzie Hall, Emma Alfred, Gina Gill and Teri-Lee Isaac, LSCFN and NND. See story on page nine. Rediscovering the Past VOLUME 11, Issue 1 SFN NEWS Spring 2015 SFN Council Highlights By Debbie Trudeau will be known. This data is being compiled for inclusion in the socio-economic reporting; the first report will be out this year. Selkirk First Na- tion is also interested in the results of this survey to better understand the Citizens’ needs and to help with future programming. Casino Mine: Selkirk First Nation Council attended a meeting with the leadership of the Little Salmon Council meets with Mayo-Tatchun MLA Jim Tredger. Carmacks First Nation to discuss the Casino Mine. The leaders have agreed for the Nations to work to- gether on elements of this project. The objectives A long with the regular business of the First Na- are for the Selkirk and Little Salmon Carmacks Na- tion, the Council has been focussing on a number of tions to be united and move forward together on initiatives this winter. The following is a brief high- this project, to come to an agreement on how the light of some of the major items: two Nations will work together, and to establish a governing structure to resolve matters together. Sel- Minto Mine: Capstone submitted their applications kirk will appoint representatives to the joint negoti- to the Yukon Environmental Socio-economic Assess- ating team. ment Board (YESAB) for Phase V/VI, and their appli- cation for the Water License is now before the Yu- Next Generation Hydro: As you may be aware, the kon Water Board. -

Alaska Highway Pipeline Inquiry

This document has been reproduce with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services, 2002, and courtesy of the Privy Council Office. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy electronically and to print in hard copy for internal use only. No part of this information may be reproduced, modified or redistributed in any form or by any means, for any purposes other than those noted above (including sales), without the prior written permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0S5 or at [email protected] [ l<cg__ro·k; 1,-re...~.......A-~J Alaska Highway Pipeline Inquiry Kenneth M. Lysyk, Chairman Edith E. Bohmer Willard L. Phelps ( '· 1"'. ·.. ~; j. 0•, Alaska Highway Pipeline Inquiry © Mi11ister of Supply and Services Canada 1977 Design: Paul Rowan, A!phatext Limited Avaifab!e by mail from Cover Photo: Andrew Hume Printing and Publishing Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada K1 A OS9 or through your bookseller. Catalogue No. CP32-31/1977 Canada: $4.50 ISBN 0-660-ll122Nl Other countries: $5.40 Price subject to change without notice. Table of Contents v Letter to the Minister 105 8 Yukon Indian Land Claim 107 Indians and Inuit in the Yukon 108 The Background to the Indian Land Claim 1 1 The Inquiry 110 The Content of the Claim 116 The View of the Indian Communities 9 2 Historical Background 118 The Question of Prejudice 120 Recommendations 19 3 The Project 123 9 Dempster Lateral 21 Background 23 The Proposal 125 Dempster Lateral or