Facebook: a Like Story Why Investors Shouldn’T Fall in Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media

What is Social media? Social media is defined as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of the World Wide Web, and that allow the creation and exchange of user content.“ (Wikipedia 2014) What is Facebook? Facebook is a popular free social networking website that allows registered users to create profiles, upload photos and video, send messages and keep in touch with friends, family and colleagues.(Dean,A.2014) History on facebook Facebook was launched in February 2004. It was founded by Mark Zuckerberg his college roommates and fellow Harvard University student Eduardo Saverin. The website's membership was initially limited by the founders to Harvard students, but was expanded to other colleges in the Boston area. By September 2006, to everyone of age 13 and older to make a group with a valid email address. Reasons for using Facebook It is a medium of finding old friends(schoolmates..etc) It is a medium of advertising any business It is a medium of entertainment Sharing your photos and videos Connecting to love ones What makes Facebook popular? The adding of photos News feed The “Like” button Facebook messenger Relationship status Timeline Some hidden features of Facebook File transfer over FB chat See who is snooping in your account An inbox you didn’t know you have You Facebook romance* Save your post for later What is Twitter? Twitter is a service for friends, family, and coworkers to communicate and stay connected through the exchange of quick, frequent messages. People post Tweets, which may contain photos, videos, links and up to 140 characters of text. -

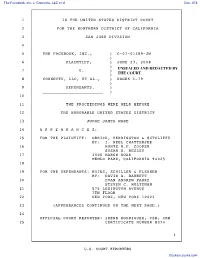

Transcript of Proceedings Held on 06/23/08, Before Judge Ware. Court

The Facebook, Inc. v. Connectu, LLC et al Doc. 474 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 2 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 3 SAN JOSE DIVISION 4 5 THE FACEBOOK, INC., ) C-07-01389-JW ) 6 PLAINTIFF, ) JUNE 23, 2008 ) UNSEALED AND REDACTED BY 7 V. ) SEALED ) THE COURT 8 CONNECTU, LLC, ET AL., ) PAGES 1-79 ) 9 DEFENDANTS. ) _______________________ ) 10 11 THE PROCEEDINGS WERE HELD BEFORE 12 THE HONORABLE UNITED STATES DISTRICT 13 JUDGE JAMES WARE 14 A P P E A R A N C E S: 15 FOR THE PLAINTIFF: ORRICK, HERRINGTON & SUTCLIFFE BY: I. NEEL CHATTERJEE 16 MONTE M.F. COOPER SUSAN D. RESLEY 17 1000 MARSH ROAD MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA 94025 18 19 FOR THE DEFENDANTS: BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER BY: DAVID A. BARRETT 20 EVAN ANDREW PARKE STEVEN C. HOLTZMAN 21 575 LEXINGTON AVENUE 7TH FLOOR 22 NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 23 (APPEARANCES CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE.) 24 OFFICIAL COURT REPORTER: IRENE RODRIGUEZ, CSR, CRR 25 CERTIFICATE NUMBER 8074 1 U.S. COURT REPORTERS Dockets.Justia.com 1 A P P E A R A N C E S: (CONT'D) 2 3 FOR THE DEFENDANTS: FINNEGAN, HENDERSON, FARABOW, GARRETT & DUNNER 4 BY: SCOTT R. MOSKO JOHN F. HORNICK 5 STANFORD RESEARCH PARK 3300 HILLVIEW AVENUE 6 PALO ALTO, CALIFORNIA 94304 7 FENWICK & WEST BY: KALAMA LUI-KWAN 8 555 CALIFORNIA STREET 12TH FLOOR 9 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94104 10 11 ALSO PRESENT: BLOOMBERG NEWS BY: JOEL ROSENBLATT 12 PIER 3 SUITE 101 13 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 14 THE MERCURY NEWS 15 BY: CHRIS O'BRIEN SCOTT DUKE HARRIS 16 750 RIDDER PARK DRIVE SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA 94190 17 18 THE RECORDER BY: ZUSHA ELINSON 19 10 UNITED NATIONS PLAZA SUITE 300 20 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94102 21 CNET NEWS 22 BY: DECLAN MCCULLAGH 1935 CALVERT STREET, NW #1 23 WASHINGTON, DC 20009 24 25 2 U.S. -

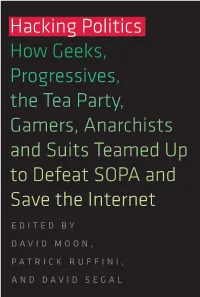

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at the CEO Summit of the Americas in Panama City, Panama April 10, 2015

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at the CEO Summit of the Americas in Panama City, Panama April 10, 2015 Well, thank you, Luis. First of all, let me not only thank you but thank our host and the people of Panama, who have done an extraordinary job organizing this summit. It is a great pleasure to be joined by leaders who I think have done extraordinary work in their own countries. And I've had the opportunity to work with President Rousseff and Peña Nieto on a whole host of regional, international, and bilateral issues and very much appreciate their leadership. And clearly, President Varela is doing an outstanding job here in Panama as well. A lot of important points have already been made. Let me just say this. When I came into office, in 2009, obviously, we were all facing an enormous economic challenge globally. Since that time, both exports from the United States to Latin America and imports from Latin America to the United States have gone up over 50 percent. And it's an indication not only of the recovery that was initiated—in part by important policies that were taken and steps that were taken in each of the countries in coordination through mechanisms like the G–20—but also the continuing integration that's going to be taking place in this hemisphere as part of a global process of integration. And I'll just point out some trends that I think are inevitable. One has already been mentioned: that global commerce, because of technology, because of logistics, it is erasing the boundaries by which we think about businesses not just for large companies, but also for small and medium-sized companies as well. -

Siff Announces Full Lineup for 40Th Seattle

5/1/2014 ***FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE*** Full Lineup Announced for 40th Seattle International Film Festival FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact, SIFF Rachel Eggers, PR Manager [email protected] | 206.315.0683 Contact Info for Publication Seattle International Film Festival www.siff.net | 206.464.5830 SIFF ANNOUNCES FULL LINEUP FOR 40TH SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Elisabeth Moss & Mark Duplass in "The One I Love" to Close Fest Quincy Jones to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award Director Richard Linklater to attend screening of "Boyhood" 44 World, 30 North American, and 14 US premieres Films in competition announced SEATTLE -- April 30, 2014 -- Seattle International Film Festival, the largest and most highly attended festival in the United States, announced today the complete lineup of films and events for the 40th annual Festival (May 15 - June 8, 2014). This year, SIFF will screen 440 films: 198 features (plus 4 secret films), 60 documentaries, 14 archival films, and 168 shorts, representing 83 countries. The films include 44 World premieres (20 features, 24 shorts), 30 North American premieres (22 features, 8 shorts), and 14 US premieres (8 features, 6 shorts). The Festival will open with the previously announced screening of JIMI: All Is By My Side, the Hendrix biopic starring Outkast's André Benjamin from John Ridley, Oscar®-winning screenwriter of 12 Years a Slave, and close with Charlie McDowell's twisted romantic comedy The One I Love, produced by Seattle's Mel Eslyn and starring Elisabeth Moss and Mark Duplass. In addition, legendary producer and Seattle native Quincy Jones will be presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the screening of doc Keep on Keepin' On. -

Fuel Rebound Loses Steam Ogy, According to People Famil- Zoom Video’S Stock Iar with the Matter

P2JW246000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ****** WEDNESDAY,SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 ~VOL. CCLXXVI NO.54 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 28645.66 À 215.61 0.8% NASDAQ 11939.67 À 1.4% STOXX 600 365.23 g 0.3% 10-YR. TREAS. À 7/32 , yield 0.672% OIL $42.76 À $0.15 GOLD $1,968.20 À $0.60 EURO $1.1913 YEN 105.96 Trump Visits Kenosha Amid Tensions Over Shooting TikTok’s What’s News AI Code Snarls Business&Finance Talks for eal talks forTikTok’s DU.S. operations have hit asnag over the ques- U.S. Deal tion of whether the app’s core algorithms canbein- cluded as part of adeal. A1 Bidders are unsure if A swift recovery in fuel China’s new export consumption by U.S. driv- restrictions cover the ers is petering out, posing new challenges to the oil video app’s algorithms market, economy and global energy industry. A1 Deal talks for TikTok’s U.S. U.S. factory output operations have hit asnag continued to grow in Au- over the question of whether gust, but the picture for the app’s core algorithms caN employment wasmixed. A2 be included as part of a deal, according to people familiar SeveraldozeN former with the matter. McDonald’sfranchisees sued the burgergiant, alleg- ing it sold Black owners By Liza Lin, subpar stores and failed to Aaron Tilley /REUTERS and Georgia Wells support their businesses. B1 Tesla said it plans to MILLIS Thealgorithms,which de- raise up to $5 billion LEAH termine the videos served to through stock offerings CAll FORORDER:President Trump said violencesparked by the policeshooting of JacobBlakeinthe Wisconsin city usersand areseen as TikTok’s from time to time. -

ZYNGA INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 2, 2018 ZYNGA INC. (Exact name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 001-35375 42-1733483 (State or Other Jurisdiction (Commission (IRS Employer of Incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 699 Eighth Street San Francisco, CA 94103 94103 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (855) 449-9642 Not Applicable (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instructions A.2. below): ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§ 230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§ 240.12b-2 of this chapter). Emerging growth company ☐ If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. -

Workshop on Venture Capital and Antitrust, February 12, 2020

Venture Capital and Antitrust Transcript of Proceedings at the Public Workshop Held by the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice February 12, 2020 Paul Brest Hall Stanford University 555 Salvatierra Walk Stanford, CA 94305 Table of Contents Opening Remarks ......................................................................................................................... 1 Fireside Chat with Michael Moritz: Trends in VC Investment: How did we get here? ........ 5 Antitrust for VCs: A Discussion with Stanford Law Professor Doug Melamed ................... 14 Panel 1: What explains the Kill Zones? .................................................................................... 22 Afternoon Remarks .................................................................................................................... 40 Panel 2: Monetizing data ............................................................................................................ 42 Panel 3: Investing in platform-dominated markets ................................................................. 62 Roundtable: Is there a problem and what is the solution? ..................................................... 84 Closing Remarks ......................................................................................................................... 99 Public Workshop on Venture Capital and Antitrust, February 12, 2020 Opening Remarks • Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice MAKAN -

CWD FTC Facebook Credits Complaint

June 28, 2011 VIA EMAIL AND FEDEX OVERNIGHT Donald S. Clark Secretary U.S. Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20580 Re: Facebook, Inc. and Facebook Credits Dear Secretary Clark: Enclosed is a Complaint, Request for Investigation, Injunction, and Other Relief submitted by Consumer Watchdog regarding Facebook, Inc. and its virtual currency, Facebook Credits. As explained in the complaint, Consumer Watchdog believes that Facebook is engaging in anticompetitive and unfair business practices in the market for virtual goods purchased in social games through its Facebook Credits terms with game developers. We request that, pursuant to the Federal Trade Commission’s authority under section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act and 16 C.F.R. § 2.5, the Commission investigate Facebook’s anticompetitive conduct and enjoin Facebook from engaging in conduct that violates sections 2 and 1 of the Sherman act, and section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act. Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Harvey Rosenfield cc via email: Jon Leibowitz, Chairman William E. Kovacic J. Thomas Rosch Julie Brill Edith Ramirez Before the Federal Trade Commission Washington, DC In the Matter of ) ) Facebook, Inc. and ) Facebook Credits ) ) ________________________________) Complaint, Request for Investigation, Injunction, and Other Relief I. Introduction 1. Consumer Watchdog submits this Complaint to the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC” or “the Commission”) requesting an investigation and injunctive relief concerning the anticompetitive terms and impact of Facebook Credits, an ambitiously revamped virtual currency system recently announced by Facebook, Inc. (“Facebook”), the dominant social networking company in the United States and the world. -

Classic Noir Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LA CONFIDENTIAL: CLASSIC NOIR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Ellroy | 496 pages | 02 Jun 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099537885 | English | London, United Kingdom La Confidential: Classic Noir PDF Book Both work for Pierce Patchett, whose Fleur-de-Lis service runs prostitutes altered by plastic surgery to resemble film stars. It's paradise on Earth Best Sound. And while Mickey Cohen was certainly a major player in the LA underworld, the bigger, though less famous, boss was Jack Dragna , who took over mob business after the murder of Bugsy Siegel in Confidential is a film-noir-inspired mystery in vivid colour. Exclusive Features. When for example, did film noir evolve into neo-noir, and what exactly constitutes neo-noir? The film's look suggests how deep the tradition of police corruption runs. The tortured relationship between the ambitious straight-arrow Det. The title refers to the s scandal magazine Confidential , portrayed in the film as Hush-Hush. Confidential Milchan was against casting "two Australians" in the American period piece Pearce wryly noted in a later interview that while he and Crowe grew up in Australia, he is British by birth, while Crowe is a New Zealander. Director Vincente Minnelli. For Myers, that meant working one-on-one with actors to find looks that both evoked the era and allowed audiences to form a meaningful connection with the characters. One of the film's backers, Peter Dennett, was worried about the lack of established stars in the lead roles, but supported Hanson's casting decisions, and the director had the confidence also to recruit Kevin Spacey , Kim Basinger and Danny DeVito. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6, 2021 No. 4 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was and our debates, that You would be re- OFFICE OF THE CLERK, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- vealed and exalted among the people. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, pore (Mr. SWALWELL). We pray these things in the strength Washington, DC, January 5, 2021. of Your holy name. Hon. NANCY PELOSI, f Speaker, House of Representatives, Amen. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Washington, DC. PRO TEMPORE f DEAR MADAM SPEAKER: Pursuant to the permission granted in Clause 2(h) of Rule II The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- THE JOURNAL of the Rules of the U.S. House of Representa- fore the House the following commu- tives, I have the honor to transmit a sealed nication from the Speaker: The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- envelope received from the White House on ant to section 5(a)(1)(A) of House Reso- January 5, 2021 at 5:05 p.m., said to contain WASHINGTON, DC, January 6, 2021. lution 8, the Journal of the last day’s a message from the President regarding ad- I hereby appoint the Honorable ERIC proceedings is approved. ditional steps addressing the threat posed by SWALWELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on applications and other software developed or f this day. controlled by Chinese companies. With best wishes, I am, NANCY PELOSI, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Mark Zuckerberg I'm Glad We Got a Chance to Talk Yesterday

Mark Zuckerberg I'm glad we got a chance to talk yesterday. I appreciate the open style you have for working through these issues. It makes me want to work with you even more. I was th inking about our conversation some more and wanted to share a few more thoughts. On the thread about lnstagram joining Facebook, I'm really excited about what we can do to grow lnstagram as an independent brand and product while also having you take on a major leadership role within Facebook that spans all of our photos products, including mobile photos, desktop photos, private photo sharing and photo searching and browsing. This would be a role where we'd be working closely together and you'd have a lot of space to shape the way that the vast majority of the workd's photos are shared and accessed. We have ~300m photos added daily with tens of billions already in the system. We have almost 1O0m mobile photos a day as well and it's growing really quickly -- and that's without us releasing and promoting our mobile photos product yet. We also have a lot of our infrastructure built p around storing and serving photos, querying them, etc which we can do some amazing things with . Overall I'm really excited about what you'd be able to do with this and what we could do together. One thought I had on this is that it might be worth you spending some time with.to get a sense for the impact you could have here and the value of using all of the infrastructure that we've built up rather than having to build everything from scratch at a startup.