Contents Tees Valley's Vital Issues 2017 Communityfoundation.Org.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washford Close, Ingleby Barwick, TS17 0FY Offers in Region Of

Washford Close, Ingleby Barwick, TS17 0FY TO VIEW CALL IAN 01642 931 320 | ONE CAREFUL OWNER | SHEPHERD BUILD DETACHED FAMILY HOME SUPERB KITCHEN/DINER | GENEROUS GARDENS FRONT & REAR | DOUBLE GARAGE & DRIVEWAY | EXCELLENT LOCATION - CLOSE TO SCHOOLS | A MUST SEE | EPC D Offers In Region Of: £230,000 Washford Close, Ingleby Barwick, DINING KITCHEN Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 0FY 5.70m (18' 8") x 4.65m (15' 3") at the widest point GREAT DETACHED FAMILY HOME - GREAT LOCATION. An excellent example of a Shepherd built home, circa 1998, with generous gardens, good sized living accommodation and a great location. Indeed, the property has been in the same family hands since it was built. Likely to attract a number of potential buyers, this four bedroom, two bathroom, detached home briefly comprises:- Entrance hall, ground floor cloaks/W.C. generous 'L' shaped lounge with front and rear aspect windows flooding the room with natural light and a feature fireplace offers a focal point. Completing the ground floor layout there is an impressive kitchen/dining room with high gloss fitted units as well as ample space for dining and lounge furniture. The first floor has a master bedroom with en-suite shower room, a LANDING further three bedrooms and family bathroom/wc. Externally there is an enclosed lawn to the front; the rear has a driveway providing ample off street parking, leading to a detached pitched roof garage. The rear garden has mature flower beds and borders containing a variety of trees plants shrubs and bushes, lawn and patio. An early viewing is recommended. -

Drinking Establishments in TS13 Liverton Mines, Saltburn

Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 drinking establishments in TS13 Single storey A4 public house Two bedroom house adjoining Liverton Mines, Saltburn-by-the-Sea Excellent development potential (STP) North Yorkshire, TS13 4QH Parking for 3-5 vehicles Great roadside position £95,000 (pub +VAT) Freehold title Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 Summary - Property Type: Drinking Establishments - Parking: Allocated Price: £95,000 Description An end-terraced property of the pub, which is a single-storey construction under flat roofing. It is attached to a two-storey house, which is connected both internally and both have their own front doors. The pub main door is located at the centre of the property and leads into, on the right a Public Bar with pool area. To the left of the entrance is a Lounge Bar. Both rooms are connected by the servery, which has a galley style small kitchen in-between both rooms. There are Gents toilets in the Bar with Ladies toilets in the Lounge. Behind the servery are two rooms, one for storage the other being the beer cellar. We are informed that the two-storey house on the end elevation is also part of the property, but is in poor decorative order and is condemned for habitation. It briefly comprises Lounge, Kitchen and Bathroom on the ground floor and has two double bedrooms and a small box room on the first floor of the house only. The property would lend itself to be used for existing use or be developed for alternative use, subject to the required planning permissions. -

Why PKA Must Divest from MGT Teesside If It Wants to Live up to Its Green Credentials

Why PKA must divest from MGT Teesside if it wants to live up to its green credentials The Danish pension fund PKA prides itself purpose-built biomass power station at of its responsible investment1, having Teesport. The plant will burn up to 1.5 divested from almost 50 coal companies million tonnes of wood pellets a year, of and from five companies involved in tar which around 1 million tonnes will be sands, while increasing investments in supplied by Enviva2, a US pellet producer ‘green energy’. In doing so, PKA has set a known to source wood by clearcutting positive example to other pension funds biodiverse, coastal, hardwood forests in and investors worldwide. However, one of the southern US3. PKA’s largest supposedly green energy The MGT Teesside plant will contribute to investments is nothing of the sort and forest destruction and biodiversity loss, risks undermining the pension fund’s will harm public health, and will be no reputation. In 2016, PKA acquired 50% of better for the climate than burning coal. shares in the UK company MGT Teesside, PKA cannot claim to be green and maintain which is building the world’s largest its investment in MGT Teesside. Undermining efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: MGT Teesside’s biomass power station basis for PKA claiming that its MGT smokestack will emit more CO2 per unit of Teesside investment is carbon neutral or at energy than that of an average coal power least low-carbon is scientifically unsound. station in Europe4. The UK government and the EU currently ignore all of the CO2 The assumption that wood-based which comes out of smokestacks of plants bioenergy is inherently carbon neutral has burning biomass, arguing that new trees been discredited by a large and growing will sequester the carbon emitted from number of peer-reviewed studies and burning wood in future5. -

Final Report

LONGITUDINAL ASSESSMENT OF LARGE SCALE REGENERATION PROJECTS: A STRATEGY FOR GREATER ESTON, REDCAR AND CLEVELAND SOUTH BANK BASELINE INFORMATION FINAL REPORT January 2011 By Gill Davidson Paul Braidford Paul Greenhalgh Fred Robinson David McGuinness Durham University Northumbria University SOUTH BANK 2010 Acknowledgements Thank you to all of the people who helped us with this research project by taking part in discussions and interviews, inviting us to attend local meetings and groups, and giving us access to a range of information. NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY AND DURHAM UNIVERSITY 2 SOUTH BANK 2010 Contents Page 1. Executive summary 6 2. Introduction 6 3. The Institute for Local Governance 9 4. Background to the study 10 5. Aims and objectives 11 6. Research methods 11 Strand 1: Documentary analysis 11 Strand 2: Consultation with key stakeholders 11 Baseline data 13 Research participants 13 7. The local context 15 The geography of South Bank 15 The history of South Bank 18 Images of South Bank in 2010 20 RESEARCH FINDINGS 24 8. South Bank today 25 Population 25 Measures of deprivation 25 9. Employment 27 Income: baseline data 27 Benefits: baseline data 27 Businesses: baseline data 28 Stakeholders’ views 29 Residents’ experiences of employment 30 Income and benefits 31 10. Education 33 Educational achievement: baseline data 33 Perceptions about achievement 36 Perceptions about local schools 36 11. Health, wellbeing and satisfaction 38 Health: baseline data 38 Pollution 38 Is South Bank a healthy place to live? 39 Local health services 40 Happiness and satisfaction levels 40 Positive things about South Bank 41 Negative things about South Bank 41 NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY AND DURHAM UNIVERSITY 3 SOUTH BANK 2010 12. -

Minerals and Waste Core Strategy

Tees Valley Joint Minerals and Waste Development Plan Documents In association with Core Strategy DPD Adopted September 2011 27333-r22.indd 1 08/11/2010 14:55:36 i ii Foreword The Tees Valley Minerals and Waste Development Plan Documents (DPDs) - prepared jointly by the boroughs of Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees - bring together the planning issues which arise from these two subjects within the sub-region. Two DPDs have been prepared. This Minerals and Waste Core Strategy contains the long-term spatial vision and the strategic policies needed to achieve the key objectives for minerals and waste developments in the Tees Valley. The separate Policies and Sites DPD, which conforms with it, identifies specific sites for minerals and waste development and sets out policies which will be used to assess minerals and waste planning applications. The DPDs form part of the local development framework and development plan for each Borough. They cover all of the five Boroughs except for the part within Redcar and Cleveland that lies within the North York Moors National Park. (Minerals and waste policies for that area are included in the national park’s own local development framework.) The DPDs were prepared during a lengthy process of consultation. This allowed anyone with an interest in minerals and waste in the Tees Valley the opportunity to be involved. An Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State carried out an Examination into the DPDs in early 2011. He concluded that they had been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 and were sound. -

Redcar-Cleveland Flyer

SPECIALIST STOP SMOKING SERVICE SESSIONS Redcar & Cleveland 2015 Wednesday Redcar Library 14.30pm - 16.00pm Kirkleatham Street, Redcar TS10 1RT Sunnyfield House Friday Community Centre, Guisborough 13.00pm - 14.30pm TS14 6BA GP PRACTICE STOP SMOKING SUPPORT Stop Smoking Support is also available from many GP practices - to find out if your GP practice provides this support, please contact the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. No appointment needed for the above Specialist Stop Smoking Sessions. Please note that clients should arrive at least 20 minutes before the stated end times above in order to be assessed. Clinics are subject to changes - to confirm availability please ring the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. Alternatively, if you have access to the internet, please visit our website S L 5 1 / for up-to-date stop smoking sessions: 3 d e t www.nth.nhs.uk/stopsmoking a d p u Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland t Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland s Stockton & Hartlepool a Stockton & Hartlepool L PHARMACY ONE STOP SHOPS Redcar & Cleveland Asda Pharmacy *P Coopers Chemist 2 North Street South Bank New Medical Centre Middlesbrough TS6 6AB Coatham Road Redcar TS10 1SR Tel: 01642 443810 Tel: 01642 483861 Boots the Chemist Harrops Chemist High Street Normanby TS6 0NH 1 Zetland Road Loftus TS13 4PP Tel: 01287 640557 Tel: 01642 452777 Lloyds Pharmacy Boots Pharmacy 35 Ennis Road, Rectory Lane Guisborough TS14 7DJ Dormanstown Tel: 01287 632120 TS10 5JZ Tel: 01642 490964 Boots Guisborough Westgate 18 Westgate Guisborough -

Descendants of Robert Appleby

Descendants of Robert Appleby Robert Appleby Mary Dennison Mary Liddle b: Bef 2 Apr 1777 in Mickley In The Parish Of b: Abt 31 Jul 1774 in Staindrop, County Durham, b: Abt 1786 in St. Hilda, South Shields, County Kirkby Malzeard, Yorkshire, England. England. Durham, England. d: 1 Nov 1847 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, m: 26 Dec 1801 in Stanwick St. John, Yorkshire, m: 13 May 1811 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, England. England. England. bu: 4 Nov 1847 in St. Marys Church, Eryholme, d: 28 Aug 1809 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, d: Abt 22 Nov 1857 in Thornaby-On-Tees, North North Yorkshire, England. England. Yorkshire, England. bu: Aug 1809 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, bu: 22 Nov 1857 in Thornaby-On-Tees, North England. Yorkshire, England. Robert Appleby Elizabeth Robinson Jane Appleby John Parkinson Thomas Appleby Anthony Appleby Eleanor Newton John Appleby Elizabeth Johnson James Appleby Margaret Workman Henry Appleby Sarah Davison William Appleby b: Abt 17 Aug 1806 in Forcett Near Gainford, b: Abt 1811 in Marrick, Yorks, ENG b: Abt 10 Jul 1808 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 12 Mar 1809 in South Cowton, North b: Bef 28 Jun 1812 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Bef 14 Aug 1814 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 29 Aug 1813 in Saint Andrews, Bishop b: Bef 23 Feb 1817 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1 Oct 1826 in Hurworth On Tees, County b: Bef 14 May 1820 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1813 in Bongate, Westmoreland, England. b: Abt 18 Aug 1822 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1827 in Hudswell, Yorkshire, England. -

Tees Valley Local Major Scheme Prioritisation Draft 3

Appendix 1 Tees Valley Local Major Scheme Prioritisation Draft 3 This note sets out the draft priority list for the Tees Valley’s 2015‐19 local major transport scheme budget, which has been devolved from central government. The management of this budget is explained in further detail within the Tees Valley Local Major Transport Schemes Assurance Framework. The process and the Tees Valley’s current position is summarised below: 1 Appendix 1 Scheme Identification and Sifting Scheme Identification A long list of highway and public transport schemes has been identified through the Tees Valley Area Action Plan (AAP). This has been achieved within the AAP by identifying congestion hotspots using the Tees Valley Multimodal Model. The model helps to predict where development and growth, specified within the Development Database, will contribute to future congestion on the Tees Valley’s Strategic Road Network. Numerous schemes are then tested within the model to identify which will mitigate these congestion hotspots and appropriate schemes are added to the long list. The long list of schemes has also been supplement by schemes identified by local authorities through work they have undertaken on a site by site basis. The model provides an assessment of each scheme and produces outputs that can be used within the sifting and prioritisation process. Sifting The sifting criteria have been selected so that any scheme that reaches the prioritisation phase would most likely be able to be developed into a WebTAG compliant business case with further work. The sifting criteria are: Value for Money: A Benefit Cost Ration (BCR) of greater than 1.5 Total Scheme Cost: Between £1.5m and £20m Timescale: A scheme would be deliverable within the funding period (2015‐19) and would provide sufficient benefits to offset its costs within 5 years of the end of the period. -

St Francis of Assisi Parish Church, Ingleby Barwick

St Francis of Assisi, Ingleby Barwick Parish Profile BARWICK WAY, INGLEBY BARWICK, STOCKTON-ON-TEES, TS17 0WD https://stfrancisib.org) 0 A message from the Rt Revd Paul Ferguson, Bishop of Whitby Thank you for your interest in the post of Vicar of Ingleby Barwick. Although Ingleby Barwick’s name reveals that there has been a settlement here for a thousand years, as you will see from the profile, today’s community is less than 50 years old, and still growing. There is a sense that it is continuing to establish its own social and civic identity, in which the role of the Church of England has a significant part to play — not least through the presence of our church primary and secondary academies. St Francis’, then, is the worshipping and serving hub for the whole community. That is reflected in the breadth of its style, at the core of which is the main Sunday eucharistic celebration. Alongside that well-established principle, the appointment of a Multiply minister (see the relevant page of the profile) has been a major step in diversifying our pattern of mission. The energy of St Francis’ worshipping life overflows into many other activities. Ingleby Barwick is an exciting place to be. There has been excellent strategic leadership during the time of its last incumbent, and scope for the parish — the largest by population in this archdeaconry — to move on further. If you come as our next vicar, you will find able lay leadership, a strong ethos of spiritual formation among worshippers, and potential to explore developments for the future. -

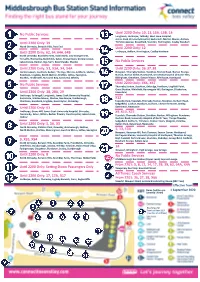

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

Ingleby Barwick 394

ingleby barwick 394 Residential 393 the forum Development 418 418 454 n 420 453 452 449 448 430 429 428 Residential 454 451 450 421 455 448 422 452 Development 455 449 430 453 450 429 451 428 446 447 456 445 Residential 445 431 456 431 Development 446 447 457 353 353 444 432 457 443 442 441 444 440 352 443 439 432 442 441 438 437 440 433 477 Residential 439 436 478 438 435 351 434 476 Development 437 436 479 351 435 434 341 352 433 476 477 340 478 479 339 348 350 339 350 349 337 338 349 338 341 340 348 Residential 347 THE FORUMGREEN Development 337 342 347 480 345 346 346 336 342 345 480 336 344 343 344 335 481 343 462 335 485 334 467 484 461 481 483 334 460 468 469 459 470 482 327 472 467 473 482 458 468 465 469 470 472 475 327 475 326 326 471 474 K 485 H LIN 465 466 473 AT 325 464 484 /CYCLE P 331 463 471 FOOT 333 483 474 332 329 325 466 330 482 464 463 330 324 331 324 487 488 486 332 328 328 489 329 323 490 333 317 493 491 487 498 492 488 323 499 489 500 501 316 317 321 500 316 493 490 320 496 497 491 319 501 498 494 322 497 322 499 492 321 496 318 320 502 495 494 315 502 503 318 319 495 315 505 504 305 304 304 314 505 AY EW IDL BR 306 305 504 303 503 314 307 302 301 313 306 303 302 307 308 313 309 308 AY EW IDL 301 BR 312 310 309 310 312 311 311 visitor centre & marketing suite Persimmon Homes (Teesside) Limited, Bowburn Industrial Estate, Durham Road, Bowburn, Co Durham DH6 5PF Telephone: 0191 3774000 www.persimmonhomes.com ingleby barwick the forum Schedule of Accommodation House Type Plot No. -

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail Car and Walk Trail this is Redcar & Cleveland Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail The History of Mining Ironstone Villages Ironstone mining began in Redcar & A number of small villages grew up in Cleveland in the 1840s, with the East Cleveland centred around the Redcar & Cleveland collection of ironstone from the ironstone mines and the differing Ironstone Heritage Trail foreshore at Skinningrove. A drift mine facilities available at these villages. celebrates the iron and steel was opened in the village in 1848. The Those that were established by ironstone industry on Teesside grew Quaker families did not permit public history of the Borough. Linking rapidly following the discovery of the houses to be built. At New Marske, Eston and Skinningrove, the Main Seam at Eston on 8th June 1850 the owners of Upleatham Mine, the by John Vaughan and John Marley. In two areas that were both Pease family, built a reading room for September a railway was under the advancement of the mining integral to the start of the construction to take the stone to both industry, the trail follows public the Whitby-Redcar Railway and the community. In many villages small schools and chapels were footpaths passing industrial River Tees for distribution by boat. The first stone was transported along the established, for example at Margrove sites. One aspect of the trail is branch line from Eston before the end Park. At Charltons, named after the that it recognises the of 1850. Many other mines were to first mine owner, a miners’ institute, commitment of many of the open in the following twenty years as reading room and miners’ baths were the industry grew across the Borough.