Pharmacists Becoming Physicians: for Better Or Worse?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

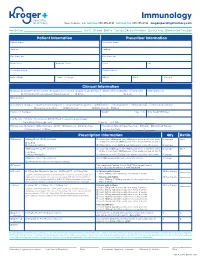

Immunology New Orleans, LA Toll Free 888.355.4191 Toll Free Fax 888.355.4192 Krogerspecialtypharmacy.Com

Immunology New Orleans, LA toll free 888.355.4191 toll free fax 888.355.4192 krogerspecialtypharmacy.com Need By Date: _________________________________________________ Ship To: Patient Office Fax Copy: Rx Card Front/Back Clinical Notes Medical Card Front/Back Patient Information Prescriber Information Patient Name Prescriber Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Main Phone Alternate Phone Phone Fax Social Security # Contact Person Date of Birth Male Female DEA # NPI # License # Clinical Information Diagnosis: J45.40 Moderate Asthma J45.50 Severe Asthma L20.9 Atopic Dermatitis L50.1 Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria (CIU) Eosinophil Levels J33 Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis Other: ________________________________ Dx Code: ___________ Drug Allergies Concomitant Therapies: Short-acting Beta Agonist Long-acting Beta Agonist Antihistamines Decongestants Immunotherapy Inhaled Corticosteroid Leukotriene Modifiers Oral Steroids Nasal Steroids Other: _____________________________________________________________ Please List Therapies Weight kg lbs Date Weight Obtained Lab Results: History of positive skin OR RAST test to a perennial aeroallergen Pretreatment Serum lgE Level: ______________________________________ IU per mL Test Date: _________ / ________ / ________ MD Specialty: Allergist Dermatologist ENT Pediatrician Primary Care Prescription Type: Naïve/New Start Restart Continued Therapy Pulmonologist Other: _________________________________________ Last Injection Date: _________ / ________ -

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist

SAMPLE JOB DESCRIPTION Clinical Pharmacist Specialist I. JOB SUMMARY The Clinical Pharmacist Specialists are responsible and accountable for the provision of safe, effective, and prompt medication therapy. Through various assignments within the department, they provide support of centralized and decentralized medication-use systems as well as deliver optimal medication therapy to patients with a broad range of disease states. Clinical Pharmacist Specialists proficiently provide direct patient-centered care and integrated pharmacy operational services in a decentralized practice setting with physicians, nurses, and other hospital personnel. These clinicians are aligned with target interdisciplinary programs and specialty services to deliver medication therapy management within specialty patient care services and to ensure pharmaceutical care programs are appropriately integrated throughout the institution. In these clinical roles, Clinical Pharmacist Specialists participate in all necessary aspects of the medication-use system while providing comprehensive and individualized pharmaceutical care to the patients in their assigned areas. Pharmaceutical care services include but are not limited to assessing patient needs, incorporating age and disease specific characteristics into drug therapy and patient education, adjusting care according to patient response, and providing clinical interventions to detect, mitigate, and prevent medication adverse events. Clinical Pharmacist Specialists serve as departmental resources and liaisons to other -

Medical School

Medical School Texas A&M Professional School Advising can advise you realistically on whether you are a competitive applicant for admission to medical school, however only you can decide if medical school is truly what you want to do. One way to explore your interest is to gain exposure by volunteering and shadowing in the different healthcare professions we advise for. You can also observe or shadow a physician and talk to professionals in the different fields of healthcare. Another way is to read information about professional schools and medicine as a career and to join one of the campus pre-health organizations. What type of major looks best? Many applicants believe that medical schools want science majors or that certain programs prefer liberal arts majors. In actuality medical schools have no preference in what major you choose as long as you do well and complete the pre-requisite requirements. Texas A&M does not have a pre-medical academic track which is why we suggest that you choose a major that leads to what you would select as an alternative career. The reason for this line of logic is that you generally do better in a major you are truly passionate and interested in and in return is another great way to determine whether medicine is the right choice. Plus an alternative career provides good insurance if you should happen to change direction or postpone entry. Texas A&M University offers extensive and exciting majors to choose from in eleven diverse colleges. If your chosen major does not include the prerequisite courses in its curriculum, you must complete the required courses mentioned below either as science credit hours or elective credit hours. -

Download Pharmacy School Admissions Guide As a Printable

Pharmacy School Admissions Guide Pharmacy is the branch of health sciences that deals with the preparation, dispensing, and proper utilization of drugs. A pharmacist is a health care professional who is licensed to prepare and sell or dispose of drugs and compounds and can make up prescriptions. Most pharmacy schools do not require you to complete an undergraduate major, though you may be more competitive for admission with a degree. Each school varies in its expectations of successful applicants, so the best places to check for the latest information are the websites of the schools in which you are most interested, and the admissions officers at those schools. The UA Health Professions Advising Office can assist you as well. PREREQUISITES: It is critical to be aware of the pharmacy school admission requirements early on in college so that you can arrange your coursework appropriately. Unlike many other health professional schools, each pharmacy school varies considerably in what courses it expects of its applicants. The undergraduate requirements at the two Alabama pharmacy schools, The McWhorter School of Pharmacy at Samford University and the Harrison School of Pharmacy at Auburn University, for example: SAMFORD AUBURN General Chemistry: CH 101 and CH 102 or honors General CH 101 and CH 102 or honors equivalent Chemistry: equivalent Organic Chemistry: CH 231, CH 232, and CH 237 (lab) Organic CH 231, CH 232, and CH 237 (lab) Chemistry: Anatomy and BSC 215 and BSC 216 (or BSC 400, Anatomy and BSC 215 and BSC 216 (or BSC 400, Physiology: -

STEM Disciplines

STEM Disciplines In order to be applicable to the many types of institutions that participate in the HERI Faculty Survey, this list is intentionally broad and comprehensive in its definition of STEM disciplines. It includes disciplines in the life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, mathematics, computer science, and the health sciences. Agriculture/Natural Resources Health Professions 0101 Agriculture and related sciences 1501 Alternative/complementary medicine/sys 0102 Natural resources and conservation 1503 Clinical/medical lab science/allied 0103 Agriculture/natural resources/related, other 1504 Dental support services/allied 1505 Dentistry Biological and Biomedical Sciences 1506 Health & medical administrative services 0501 Biochem/biophysics/molecular biology 1507 Allied health and medical assisting services 0502 Botany/plant biology 1508 Allied health diagnostic, intervention, 0503 Genetics treatment professions 0504 Microbiological sciences & immunology 1509 Medicine, including psychiatry 0505 Physiology, pathology & related sciences 1511 Nursing 0506 Zoology/animal biology 1512 Optometry 0507 Biological & biomedical sciences, other 1513 Osteopathic medicine/osteopathy 1514 Pharmacy/pharmaceutical sciences/admin Computer/Info Sciences/Support Tech 1515 Podiatric medicine/podiatry 0801 Computer/info tech administration/mgmt 1516 Public health 0802 Computer programming 1518 Veterinary medicine 0803 Computer science 1519 Health/related clinical services, other 0804 Computer software and media applications 0805 Computer systems -

Pharmacist-Physician Team Approach to Medication-Therapy

Pharmacist-Physician Team Approach to Medication-Therapy Management of Hypertension The following is a synopsis of “Primary-Care-Based, Pharmacist-Physician Collaborative Medication-Therapy Management of Hypertension: A Randomized, Pragmatic Trial,” published online in June 2014 in Clinical Therapeutics. What is already known on this topic? found that the role of the pharmacist differed within each study; whereas some pharmacists independently initiated and High blood pressure, also known as hypertension, is a changed medication therapy, others recommended changes major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, the leading to physicians. Pharmacists were already involved in care in all cause of death for U.S. adults. Helping patients achieve but one study. blood pressure control can be difficult for some primary care providers (PCPs), and this challenge may increase with After reviewing the RCTs, the authors conducted a randomized the predicted shortage of PCPs in the United States by 2015. pragmatic trial to investigate the processes and outcomes that The potential shortage presents an opportunity to expand result from integrating a pharmacist-physician team model. the capacity of primary care through pharmacist-physician Participants were randomly selected to receive PharmD-PCP collaboration for medication-therapy management (MTM). MTM or usual care from their PCPs. The authors conducted MTM performed through a collaborative practice agreement the trial within a university-based internal medicine medical allows pharmacists to initiate and change medications. group where the collaborative PharmD-PCP MTM team Researchers have found positive outcomes associated included an internal medicine physician and two clinical with having a pharmacist on the care team; however, the pharmacists, both with a Doctor of Pharmacy degree, at least evidence is limited to only a few randomized controlled 1 year of pharmacy practice residency training, and more than trials (RCTs). -

Application for Approval of ACPE Pharmacy School Course(S)

9960 Mayland Drive, Suite 300 Henrico, Virginia 23233 (804) 367-4456 (Tel) (804) 527-4472 (Fax) [email protected] www.dhp.virginia.gov/pharmacy APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF ACPE ACCREDITED PHARMACY SCHOOL COURSE(S) FOR CONTINUING EDUCATION CREDIT Name of Pharmacist or Pharmacy Technician Street Address City State Zip Code Current license or registration number (if applicable) Social S ecurity Number or DMV control number on file with Board Name of Pharmacy School Street Address Telephone Number City State Zip Code Type of Program Pharm.D.; Ph. D.; Other (explain) Beginning D ate (of courses for one calendar year) Expected Completion Date (of courses for same calendar year) IMPORTANT: Please complete page 2 of this application and attach a copy of your program schedule to include the name of each course, description of course content, type of course (i.e. classroom or lab), and number of hours per week spent in each course. Experiential rotations/practical experience/clerkships will not be approved for CE credit. FOR BOARD USE ONLY: Preliminary approval conditioned upo n satisfactory completion of course The Virginia Board of Pharmacy accepts this program to substitute for contact hours of continuing pharmacy education for the calendar year upon certification by the Dean or Registrar that this applicant has successfully completed this coursework and has received academic credit.. Signature of the Executive Director for the Board of Pharmacy Date Revised 6/2020 Application for ACPE Pharmacy School Program for CE Credit Page 2 This section is to be completed for prior approval of pharmacy school program for continuing education credits by the Board of Pharmacy. -

Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy, Shenandoah University Pharmacy Postgraduate Education Hello. My Name Is Mark Johnson and I

Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy, Shenandoah University Pharmacy Postgraduate Education Hello. My name is Mark Johnson and I’m on faculty here at the SU BJD SOP and Director of Postgraduate Education. I’m very glad to hear of your interest in pharmacy and Shenandoah University. Pharmacy is a very exciting field offering many opportunities from community pharmacy, hospital pharmacy, drug industry, regulatory affairs, and many others. Some positions in pharmacy now may prefer or require some advanced training after completion of the Doctor of Pharmacy degree. This advanced postgraduate training includes residencies, fellowships, and other graduate degrees. The Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy has a long track record of success and involvement in postgraduate pharmacy training. All of these postgraduate pharmacy education programs are highly competitive and students apply in their fourth year of pharmacy school. Residency training is divided into two postgraduate years. Postgraduate year one (PGY-1) offers more generalized training, providing residents exposure to a broad range of disease states and patients. These residencies are done at hospitals, community pharmacies, managed care pharmacies, and ambulatory care clinics. Postgraduate year two (PGY-2) emphasizes a specific area of interest and helps lead to specialization in that field (such as critical care, oncology, pediatrics, etc.). Fellowships focus more on research and are often associated with Schools of Pharmacy and drug industry. There are also graduate degree programs as -

Course-Catalog.Pdf

2020-2021 SCHOOL OF MEDICINE COURSE CATALOG 1 Introduction The School of Medicine Student Course Catalog is a reference for medical and academic health students and others regarding the administrative policies, rules and regulations of Emory University and the Emory University School of Medicine. In addition, the Student Handbook contains policies and procedures for areas such as admissions, academic and professional standards, progress and promotion, financial aid, student organizations, disability insurance, academic and personal counseling, and student health. It is the responsibility of each student enrolled in the Emory University School of Medicine programs to understand and abide by the regulations and policies within the course catalog, student handbook, and within Emory University. Accreditation Statement Emory University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award associate, baccalaureate, master, education specialist, doctorate and professional degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Emory. Nondiscrimination Statement Emory University is an inquiry-driven, ethically engaged, and diverse community dedicated to the ideals of free academic discourse in teaching, scholarship, and community service. Emory University abides by the values of academic freedom and is built on the assumption that contention among different views is positive and necessary for the expansion of knowledge, both for the University itself and as a training ground for society at large. Emory is committed to the widest possible scope for the free circulation of ideas. The University is committed to maintaining an environment that is free of unlawful harassment and discrimination. -

Pharmacy/Medical Drug Prior Authorization Form

High Cost Medical Drugs List High Cost Medical Drugs administered by Health Alliance™ providers within physician offices, infusion centers or hospital outpatient settings must be acquired from preferred specialty vendors. Health Alliance will not reimburse any drug listed as a “High Cost Medical Drug,” whether obtained from the provider’s own stock or via “buy-and-bill.” This drug list does not apply to members with Medicare coverage. Information on how to acquire these medications is located at the end of this document. Recent Updates Preferred Contact Drug Therapy Drug Name Code PA Effective Change Vendor Number Oncology – Injectable DARZALEX FASPRO J9144 YES 10/1/2021 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Added High Cost Medical Drug List Preferred Contact Drug Therapy Drug Name Code PA Effective Vendor Number Acromegaly SANDOSTATIN J2353 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Acromegaly SOMATULINE J1930 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products JETREA J7316 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products PROLASTIN J0256 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products QUTENZA J7336 NO 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products REVCOVI J3590 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products RADICAVA J1301 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products SIGNIFOR J2502 YES 7/1/2020 Accredo® 866-759-1557 Additional Products SPRAVATO J3490 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products STRENSIQ J3590 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products THIOTEPA J9340 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Allergic Asthma CINQAIR J2786 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 -

Curriculum Inventory (CI) Glossary Last Updated 11/30/2020 1 © 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges

Curriculum Inventory (CI) Glossary This glossary lists and defines terms commonly used for the AAMC CI program. This CI Glossary is intended for use by schools for curriculum occurring between July 1, 2020 -June 30, 2021, for upload to the AAMC in August 2021. Contents Concepts Related to CI Content...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Academic level and academic year................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Academic level............................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Current academic year ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Previous academic year ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Events.................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Events ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

College of Pharmacy Bulletin 2017-2018

COLLEGE OF PHARMACY BULLETIN 2017-2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Calendar ..................................................................................................3 General Information .................................................................................................5 College of Pharmacy History ...................................................................................6 Doctor of Pharmacy Program ..................................................................................8 Program of Study .........................................................................................8 Admission to the Professional Program .......................................................8 Application Guidelines ................................................................................9 Tuition, Fees, and Other Expenses ..............................................................9 Financial Aid ..............................................................................................10 Pre-Pharmacy Curriculum .....................................................................................10 College of Pharmacy Faculty .................................................................................12 Doctor of Pharmacy Curriculum ............................................................................15 Course Descriptions ...............................................................................................19 Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences ..................................................19