First to Second Year Player Production in the Nhl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Toice! Hit

FALL 2019 THEReady ToICE! Hit JAY BOUWMEESTER INTEGRAL TO BLUES STANLEY CUP WIN Louie & jake debrusk A mutual admiration for each other's game INSIDE What’s INSIDEMESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT HOCKEY EDMONTON 5. OF HOCKEY EDMONTON 20. SUBWAY PARTNERSHIP MESSAGE FROM THE PUBLISHER 7. OF THE HOCKEY MAGAZINE 21. THE REF COST US THE GAME MALE MIDGET AAA EXCITING CHANGES OCCURING JAY BOUWMEESTER 8. IN EDMONTON INTEGRAL TO BLUE’S STANLEY 23. CUP VICTORY IN JUNE, 2019 EDMONTON OILERS 2ND SHIFT PROGRAM 10. BOSTON PIZZA RON BRODEUR SCHOLARSHIP AWARD FEATURED ON THE COVER 26. 13. NICOLAS GRMEK HOCKEY NIGHT IN CANADA LOUIE & JAKE DEBRUSK 30. IN CREE FATHER & SON - A MUTUAL 14. ADMIRATION FOR EACH OTHER’S GAME SPOTLIGHT ON AN OFFICIAL BRETT ROBBINS EDMONTON ARENA 32. 18. LOCATOR MAP Message From Hockey Edmonton 10618- 124 Street Edmonton, AB T5N 1S3 Ph: (780) 413-3498 • Fax: (780) 440-6475 www.hockeyedmonton.ca Welcome back! I hope you had a chance to get away with your family To contact any of the Executive or Standing and friends to enjoy summer somewhere that was hot and warm. Committees, please visit our website It’s amazing how time speeds by. It feels like just yesterday we were dropping the puck at the ENMAX Hockey Edmonton Championships and going into our annual general meeting where I became president HOCKEY EDMONTON | EXECUTIVES of Hockey Edmonton. Fast forward to now when player evaluations President: Joe Spatafora and team selections have ended and we are into our players’ first practices, league games, tournaments and team building events. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

O-Pee-Chee 1989

1989-90 OPC Set of 270 1989-90 O-Pee-Chee Set of 270 (loose stickers) 4 Key Rookie (RC) Stickers Joe Sakic, Tony Granato, Trevor Linden and Craig Janney. Sticker History This was the third O-Pee-Chee sticker series where the sticker backs were printed on more glossy cardboard stock than the thinner paper backings of the previous 8-9 years. There are 182 physical stickers where 88 of those are paired up with another sticker from the set. For the third year in a row, the traditional sticker package that had to be “ripped” open from their vacuum package, was replaced by wax type packs that were only previously used to encase hockey cards. The stickers from this year are by far the easiest to find of the 9 years that O-Pee-Chee produced stickers and are still readily available. The sticker album, in contrast, is the hardest to find of the 9 years of O-Pee-Chee stickers. This was the first year that Wayne Gretzky appears in an L.A.Kings uniform. The sticker album featuring Lanny McDonald is by far the hardest album to find in MINT unused condition in the O-Pee-Chee Hockey sticker line. O- Pee-Chee distributed these stickers out of London, Ontario in Canada. Sticker Facts The size of each full sticker is 5.4 cm X 7.6 cm (2.13 in X 3 in). There were 48 packages in each wax box which originally retailed for $0.35 per pack. Each package contained 6 stickers. The minimum number of packages needed to make a full set (assuming absolutely no doubles) is 31. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 02/09/19 Anaheim Ducks Colorado Avalanche 1129734 Hits keep coming for Ducks goalie John Gibson, who sits 1129765 Why the Avalanche won’t trade any of its top prospects or out Friday’s practice draft picks 1129735 Jakob Silfverberg on the Ducks and trade deadline 1129766 Five takeaways from the Avs ninth overtime loss of the chatter: ‘I want to stay’ season Arizona Coyotes Columbus Blue Jackets 1129736 Who will be the first Coyotes player to 12 goals? Players, 1129767 Artemi Panarin says he'll test free agency fans give their votes 1129768 Blue Jackets: Artemi Panarin switches to Sergei 1129737 Arizona Coyotes defenseman Kyle Capobianco done for Bobrovsky's agent season 1129769 Blue Jackets 4, Coyotes 2: Five takeways 1129738 Coyotes trade Dauphin, Helewka to Nashville for Emil 1129770 Artemi Panarin, in first English interview, smiles, jokes and Pettersson laughs through wide-ranging conversation 1129771 Artemi Panarin fires agent, hires Sergei Bobrovsky’s rep, Boston Bruins Paul Theofanous 1129739 Artemi Panarin remains the big prize in trade talks 1129772 G53: With top line benched, Blue Jackets lean on Boone 1129740 Reshuffled Bruins lines gave Bruce Cassidy food for Jenner for goals, grunt work thought 1129741 Bruins’ Jake DeBrusk works to find game, end drought Dallas Stars 1129742 Bruins notebook: Team focuses on keeping lead 1129774 Stars goaltender Ben Bishop placed on injured reserve, 1129743 Grzelcyk (lower body) missing from Bruins practice, will be eligible to play again in Florida expected out Saturday vs. Kings 1129775 The Dallas Stars' first moms trip is missing the woman 1129744 Play of Cehlarik giving the Bruins some options ahead of who had long lobbied for it. -

Rifle Submission.Pdf

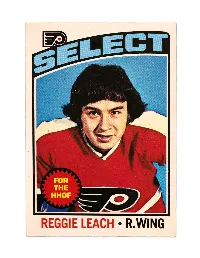

John K. Samson PO Box 83‐971 Corydon Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3M 3S3 February 23, 2013 Mr. Bill Hay, Chairman of the Board, and Members of the Selection Committee The Hockey Hall of Fame 30 Yonge Street Toronto, Ontario M5V 1X8 Dear Mr. Bill Hay, Chairman of the Board, and Members of the Selection Committee, Hockey Hall of Fame; In accordance with the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Policy Regarding Public Submission of Candidates Eligible for Election into Honoured Membership, please accept this bona‐fide submission putting forth the name Reggie Joseph Leach for your consideration. A member of the Berens River First Nation, Reggie Joseph Leach was born in 1950 in Riverton, Manitoba. While facing the injustices of racism and poverty, and playing on borrowed skates for much of his childhood, Leach’s terrific speed and honed shooting skills earned him the nickname “The Riverton Rifle.” He went on to become one of the most gifted and exciting hockey players of his generation. His pro‐hockey accomplishments are truly impressive: two‐time NHL All Star, Conn Smythe Trophy winner (the only non‐goalie from a losing team to ever win it), 1975 Stanley Cup winner, 1976 Canada Cup winner, and Regular Season Goal Scoring Leader, to name a few. His minor league record is remarkable, too. As a legendary member of the MJHL/WCJHL Flin Flon Bombers, Mr. Leach led the league in goal‐scoring twice, and was placed on the First All‐ Star team every season he played. The statistical analysis in the pages that follow, prepared by Phil Russell of Dozen Able Men Data Design (Ottawa, Ontario), makes a clear and persuasive case that Mr. -

Varsity Magazine Vol 7 No 33

CONTENTS APRIL 5, 2017 ▪ VOLUME 7, ISSUE 33 LAUREN ARNDT ADVERSITY AND OPPORTUNITY Injuries ended their seasons. But for Jack Cichy and Chris Orr, the road back has provided more than rehab and healthy bodies. It’s given them a clearer outlook on football and life. JACK MCLAUGHLIN FEATURES SOFTBALL IN [FOCUS] WALK-ON SUCCESS The week's best photos Wisconsin’s culture of finding and BY THE NUMBERS growing local and regional talent is Facts and figures on UW building success for softball. WHAT TO WATCH Where to catch the Badgers LUCAS AT LARGE ATHLETES OF THE MONTH Badgers’ best & brightest LEGEND OF THE MIC ASK THE BADGERS After starting his storied career Why Badgers fans are great calling Wisconsin hockey games, ICON SPORTSWIRE NHL Hall of Fame announcer Bob Miller is ready to turn off the mic. BADGERING Sarah Disanza (Track & Field) -SCROLL FOR MORE- INSIDE TRACK & FIELD Arizona’s Shootout up next Wisconsin Athletic Communications Kellner Hall, 1440 Monroe St. Madison, WI 53711 VIEW ALL ISSUES Brian Lucas Director of Athletic Communications Jessica Burda Director of Digital Content Managing Editor Julia Hujet Editor/Designer Mike Lucas Senior Writer Andy Baggot Writer Matt Lepay Columnist Chris Hall, Jerry Mao, Brandon Spiegel Video Production Max Kelley Advertising Drew Pittner-Smith Distribution Contributors Paul Capobianco, Kelli Grashel, A.J. Harrison, Brandon Harrison, Patrick Herb, Brian Mason, Diane Nordstrom Photography David Stluka, Neil Ament, Greg Anderson, Bob Campbell, The Players Tribune, Cal Sport Media, Icon Sportswire Cover Photo: David Stluka Problems or Accessibility Issues? [email protected] © 2017 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. -

An Application to Salary Determination in the National Hockey League

Team Effects on Compensation: An Application to Salary Determination in the National Hockey League by Todd Idson, Columbia University Leo H. Kahane, California State University, Hayward September 1995 1994-95 Discussion Paper Series No. 743 Team Effects on Compensation: An Application to Salary Determination in the National Hockey League Todd L. Idson Columbia University Leo H. Kahane California State University, Hayward September 1995 We would like to thank Larry Kahn and Joe Tracy for helpful comments. All errors, though, remain the responsibility of the authors. Abstract Studies of salary determine largely model pay as i function of the attributes ot the individual and the workplace (i.e. employer size, job characteristics, and so forth). This paper empirically investigates an additional factor that may influence individual pay, specifically coworker productivity. Data from the National Hockey League are used since both salary and teammate performance measures are readily available. We find that team attributes have both direct effects on an individual's pay, and indirect effects by altering the rates at which individual player productive characteristics are valued. I. Introduction When complementarity exists between labor inputs, individual productivity may be poorly measured by treating the individual worker separately from the character of the organization, or team, within which he works. Namely, the same individual may have different measured productivity when working in different settings since his co-workers will offer different degrees of help.1 If such complementarity between human capital inputs is present, say a team dynamic, it will imply the existence of both team and individual effects on productivity, and hence compensation. -

42!$)4)/. Tradition Trad T Tra Rad R a Ad D Itio Iti I Ti Tio O N

42!$)4)/. TRADITION TRAD T TRA RAD R A AD D ITIO ITI I TI TIO O N CHICAGOBLACKHAWKS.COMCCHICHCHICHICHHIICICAGOBAGAGOAGGOGOBOOBBLLACLACKLAACACKACCKKHAWKHAHAWHAWKAWAWKWKSCOSSCS.COS.S.C.CCOCOM 23723737 2%4)2%$37%!4%23 TRADITION 3%!3/.37)4(",!#+(!7+3: 22 (1958-1980)9880)0 37%!4%22%4)2%$ October 19, 1980 at Chicagoaggo Stadium.StS adadiuum.m. ",!#+(!7+3#!2%%2()'(,)'(43 Playedyede hishiss entireenttirre 22-year222 -yyeae r careercacareeere withwitith thethhe Blackhawks ... Led the Blackhawks to the 1961 Stanleyey CupCuC p andana d pacedpacec d thetht e teamtet amm inin scoringscs oro inng throughout the playoffs ... Four-time Art Ross Trophy winner (1964, 1965, 1967 & 1968) ... Two-time Hart Trophy Winner (1967 & 1968) ... Two-time Lady Bing Trophy winner (1967 & 1968) ... Lester Patrick Trophy winner (1976) ... Six-time First Team All-Star (1962, 1963, 1964, 1966, 1967 & 1968) ... Only player in NHL history to win the Art Ross, Hart, and Lady Bing Trophies in the same season (1966-67 & 1967-68) ... Two-Time Second Team All-Star (1965 & 1970 ... Hawks all-time assists leader (926) ... Hawks all-time points leader (1,467) ... Second to Bobby Hull in goals (541) ... Blackhawks’ leader in games played (1,394) ... Hockey Hall of Fame inductee (1983) ... Blackhawks’ captain in 1975-76 & 1976-77 ... First Czechoslovakian-born player in the NHL ... Member of the famous “Scooter Line” with Ken Wharram and Ab McDonald, and later Doug Mohns ... Named a Blackhawks Ambassador in a ceremony with Bobby Hull at the United Center on March 7, 2008. 34/3( 238 2009-10 CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS MEDIA GUIDE 2%4)2%$37%!4%23 TRADITION TRAD ITIO N 3%!3/.37)4(",!#+(!7+33%!3/3 ..33 7)7)4(( ",!#+#+(!7! +3 155 (1957-1972)(1919577-1-1979722)) 37%!4%22%4)2%$37%!4%22%4)2%$ DecemberDecec mbm ere 18,18,8 1983198983 atat ChicagoChih cacagoo Stadium.Staadid umm. -

Pressrelease

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 9th, 2014 P R E S S R E L E A S E Interview with Ranger Bernie Nicholls this Sunday, October 12th Nicholls to discuss his time with the Rangers, offer some insights on the current team and what he is up to today This Sunday, October 12th at 8:00pm, SPORTSTALK1240 host Bill Donohue will welcome former New York Rangers center Bernie Nicholls to the show. Nicholls is expected to join the show at about 8:45pm, and the interview should take place for approximately 15 minutes. Donohue will speak with Nicholls about his time playing with the team, his thoughts on the current Rangers squad and some of what he is doing today including his new sports stock market app. The show can be heard on Long Island’s AM1240-WGBB, on your iPhone using the TuneIn app, or online at http://sportstalk1240.com. Nicholls was acquired by the Rangers on January 20, 1990 from the Los Angeles Kings in exchange for Tomas Sandstrom and Tony Granato. He played 104 games for the Rangers between 1989-90 and 1991-92, scoring 37 goals along with 73 assists. Nicholls was dealt to the Edmonton Oilers along with Steven Rice and Louie DeBrusk in 1992 as part of a blockbuster deal that saw Mark Messier join the Rangers. Nicholls also spent two seasons with the New Jersey Devils from 1992-93 to 1993-94, playing in 84 games and scoring 24 goals and 32 assists during his time in New Jersey. Other guests on the program this Sunday will include former Raiders wide receiver Tim Brown and former Penn State quarterbacks coach Jay Paterno. -

Brampton Sports Hall of Fame

Bramp ton Sports Hall of Fame Board of Frank Russell Don Doan Jim McCurry Chair man Secretary Honourary Gov er nors Gov er nor Everett Coates Ken Giles Bob Hunter Treasurer City of Bramp ton Jim Miller John MacRae Harvey Newlove HISTORY The Brampton Sports Hall of Fame was founded in 1979 by a group of truly dedicated sport enthusiasts, in conjunction with the Brampton Parks and OF THE Rec re a tion Department. BRAMPT ON SPORTS The purpose of the Sports Hall of Fame is to provide recognition for those residents of Brampton who, in their time of residency in Brampton, HALL OF were dis tin guished as being an exceptional athlete, executive member or FAME coach. There are two categories of membership into the City of Brampton Sports Hall of Fame: ATHLETES and BUILDERS - all members other than athletes. In clud ing the induction of E. Herbert Armstrong as the Hall’s fi rst charter member at the inaugural banquet held November 25th, 1981, a total of 55 ATHLETES and 26 BUILDERS have been recognized. As the 20th Century draws to a close, let us refl ect proudly on the outstanding accomplishments of our fi rst 81 Inductees. With the 21st Century just around the corner, we look forward with great anticipation and enthusiasm to future suc cess es and achievements. Plan now to join us each year at our new home in the Brampton Centre for Sports and Entertainment to recognize and celebrate Brampton’s City of Bramp ton MARK BOSWELL Mark Boswell of Brampton capped his 1999 medal performance by winning a silver medal in the high jump at the IAAF World Championship in Seville, Spain. -

2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey Final Checklist

2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey Final Checklist Set Subset Name Checklist Bronze Platinum Red Emerald Gold Plates 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Alexander Mogilny GC-AM 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bernie Geoffrion GC-BF 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bernie Nicholls GC-BN 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bill Barber GC-BB 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bobby Carpenter GC-BC 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bobby Hull GC-BH 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Brendan Shanahan GC-BS 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Brett Hull GC-BH 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Brian Bellows GC-BB 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Bryan Trottier GC-BT 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Cam Neely GC-CN 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Charlie Simmer GC-CS 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Dale Hawerchuk GC-DH 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Dave Andreychuk GC-DA 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Dino Ciccarelli GC-DC 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Gary Roberts GC-GR 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Glenn Anderson GC-GA 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Guy Lafleur GC-GL 12 5 3 2 1 No 2016 Leaf Lumber Kings Hockey 50 Goal Club Jari Kurri GC-JK -

2020 Nhl Draft Presented by Ea Sports Nhl 21 Information Guide

2020 NHL DRAFT PRESENTED BY EA SPORTS NHL 21 INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 NHL Draft Order of Selection............................................................................................................................... 3 2020 NHL Draft Picks by Team.................................................................................................................................... 7 Summary of Traded 2020 NHL Draft Picks ................................................................................................................... 8 Draft Order Procedure for 2020 NHL Draft.................................................................................................................. 14 2020 NHL Draft Lottery Results ................................................................................................................................. 15 All-Time NHL Draft Lottery Results ............................................................................................................................ 16 2020 NHL Draft Quick Hits ........................................................................................................................................ 17 Notable Team Picks in 2020 Round 1 Draft Slot(s)...................................................................................................... 21 NHL Central Scouting Final Rankings for 2020 NHL Draft North American Skaters ...............................................................................................................................