Why Misogynists Make Great Informants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Orleans University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 Phases of a Man Called 'Moon': Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974 Frank L. Straughan Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Straughan, Frank L. Jr., "Phases of a Man Called 'Moon': Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1347. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1347 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phases of a Man Called ―Moon‖: Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Frank L. -

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism That Are Just a Click Away (With Links)

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism that Are Just a Click Away (with links) Ida B. Wells : a Passion For Justice [1989] [San Francisco, California, USA] : Kanopy Streaming, 2015. Video — 1 online resource (1 video file, approximately 53 min.) : digital, .flv file, sound Sound: digital. Digital: video file; MPEG-4; Flash. Summary Documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Though virtually forgotten today, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a household name in Black America during much of her lifetime (1863-1931) and was considered the equal of her well-known African American contemporaries such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison reads selections from Wells' memoirs and other writings in this winner of more than 20 film festival awards. "One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap." - Ida B. Wells "Tells of the brave life and works of the 19th century journalist, known among Black reporters as 'the princess of the press, ' who led the nation's first anti-lynching campaign." - New York Times "A powerful account of the life of one of the earliest heroes in the Civil Rights Movement...The historical record of her achievements remains relatively modest. This documentary goes a long way towards rectifying that egregious oversight." - Chicago Sun-Times "A keenly realized profile of Ida B. -

The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly

VOLUME XXXVII The Historic New Orleans NUMBER 1 Collection WINTER 2020 Quarterly Shop online at www.hnoc.org/shop SPORTING LIFE: 20 Transformative Tales Tennis enthusiasts enjoying an afternoon “Tennis Tea” at the New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club ca. 1898 courtesy of Tulane University Special Collections, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, the Louisiana Research Collection, New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club Records ON THE COVER Billy Kilmer handing off to Tony Baker (detail) between 1967 and 1970 gift of the Press Club of New Orleans, 1994.93.41 FROM THE PRESIDENT History is constantly being created. The actions of today become the stories of tomorrow. Which events will be preserved, remembered, valued? Which will be lost, forgotten, neglected? There is much in this issue of the Quarterly to remind us of the deceptively simple concept that some of the experiences of our lives will be historically significant for future generations. Sometimes we think we know history when it happens, but more often, we are unaware of the moments in our lives that will make a lasting mark. Curator Mark Cave’s article, CONTENTS “Local Legends,” about our latest exhibition, Crescent City Sport, describes episodes in sports history that fit each category. A sense of significance must have abounded while the ON VIEW / 2 action unfolded at the Saints’ first regular season game in 1967. But Newcomb profes- Crescent City Sport: Stories of Courage sor Clara Baer, who wrote the first rulebook for women’s basketball in 1895, and, more and Change tells tales of sporting life recently, spectators at the first match of the Big Easy Rollergirls probably never imagined and civic communion in New Orleans. -

Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace

“ALBERT WOODFOX, HERMAN WALLACE and Robert Wilkerson are worth my efforts and the efforts of all who believe that you must !ght injustice where you !nd it.” DAME ANITA RODDICK Founder of The Body Shop and human rights activist “THE RELENTLESS PROSECUTION OF THE Angola 3 in the infamous Penitentiary at Angola…is another in a long line of cases in this country involving egregious prosecuto- rial misconduct. The interests of justice can only be served by ending the prosecution and dropping the charges against them, and setting them free.” RAMSEY CLARK Former U.S. Attorney General “FRIENDSHIPS ARE FORGED IN STRANGE places. My friendship with Robert King, and the other two Angola 3 men Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, is based on respect. These men, as Robert reveals in this stunning account of his life, have fought tirelessly to redress injustice, not only for themselves, but for others. Since his release in 2001 Robert has been engaged in the !ght to rescue these men from a cruel and repressive administration that colludes in deliberate lying and obfuscation to keep them locked up. This is a battle Robert is determined to win, and we are determined to help him.” G ORDON RODDICK Co-founder of The Body Shop and human rights activist “THIS BOOK IS A SEARING INDICTMENT OF the contemporary USA, a rich and commanding nation, which still crushes the hopes and aspirations of so many poor black Americans and criminalizes their young. Robert Hillary King’s account of his horrifying 29 years in prison for a crime he did not commit should shame all of us who believe that justice has to be at the heart of any democracy worthy of that name.” (BARONESS) HELENA KENNEDY QC Member of the House of Lords, Chair of Justice, UK “WHEN THERE IS A TRAIN WRECK, THERE IS a public inquiry, to try to avoid it recurring. -

The Bay View's Website, Was Badly

The Bay View’s website, www.sfbayview.com, was badly hacked but is coming back – soon. Meanwhile, here’s a story from this week’s printed Bay View: Malik Rahim and Kiilu Nyasha, two Black Panthers who spread revolutionary love every day of their lives (Photo: Kamau Amen-Ra) Black August Commemoration 2006 Commentary by Kiilu Nyasha This Black August marks the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of the Gulf states, especially New Orleans. We also just witnessed the horrific U.S.-backed Israeli bombing of Lebanon. It’s ironic that New Orleans a year later looks much like bombed out Lebanon. And in both cases, the people’s organizations are volunteering services and assistance to repair the damages and meet survivors’needs: the Common Ground Collective in New Orleans and Hezbollah in Lebanon. This year also marks the 40th anniversary of the Black Panther Party. Religious differences notwithstanding, Hezbollah is reminiscent of the Party, first organized to defend Black people against the predominately white, racist occupation forces, dubbed “pigs,”running amuck in our hoods, where they frequently shot, killed, brutalized and jailed unarmed Black folks. Hezbollah grew out of the original 1982 invasion and occupation of Lebanon by Israel. Like the BPP, its youthful members organized their people to fight the occupiers while meeting their basic needs – establishing medical clinics and schools, providing food, clothing and other services. Today, Hezbollah is an integral part of the Lebanese population and government – and they just waged a heroic battle against the Israeli invaders, forcing them out of Southern Lebanon once again. -

Dges and Wardens Who Have All Facilitated Wallace’S Residence in a 6-Foot-By-9- Foot Cell for 40 Years, but They Haven’T Really Made His Incarceration Possible

POV Community Engagement & Education DISCUSSION GUIDE Herman's House A Film by Angad Singh Bhalla www.pbs.org/pov LETTER FROM THE FILMMAKER NEW YORK , 2013 Someone once told me that the key to a good documentary is access. I somehow decided to make a film where I had no access to one of my main subjects, Herman Wallace, or to my primary location, his prison cell. My naïveté as a first-time film - maker protected me from conventional wisdom, but early on I realized that the whole idea of access would be crucial to the story of a man who has now spent more than four decades in solitary confinement. In another sense, it was having access that led me to this story. I befriended artist Jackie Sumell while we were painting protest signs against the impending Iraq War; I was in college at the time. When she first explained her collaborative art project with Herman Wallace, it seemed interesting to me. But only later, when I read a book composed of letters she and Wallace had written over the years as they went back and forth on what his dream home should look like, did I discover that their powerful exhibit, “The House That Herman Built,” was just the beginning of the story. When I began telling people that I was making a film about a man who has been held in solitary confinement in Louisiana state prisons since 1972, they almost in - variably responded, “How is that possible?” And then they asked, “What did he do?” The first question always intrigued me much more. -

The Common Ground Collective Was Established in the First

VOLUNTEER HANDBOOK June 2006 Common Ground Collective, 1415 Franklin St. New Orleans, LA 70117 www.commongroundrelief.org n [email protected] Solidarity Not Charity What You Will Find in the Handbook Page 2: Introduction and Background Page 4: Racism and History of Louisiana, Slavery and New Orleans Page 6: Facts Post-Katrina Page 7 The Work We Are Doing, Work Crews Page 8: Daily Schedule Page 9: Communal Living, Working with Respect, Page 10: Health and Safety Page 11: Sexual Harassment Prevention, Page 12: Dealing with NOPD Page 13: Dealing with the Media, Common Ground Projects Page 15: Meg Perry Memorial Garden and Bioremediation Project, Important Phone Numbers Page 16: Contact List Page 17: Maps “Common Ground restores hope and teaches civic responsibility” Malik Rahim, Co-founder 2 Katrina swept through the Gulf Coast. Malik Introduction Rahim, long-term community organizer, member of the Black Panther Party and Green Party Candidate The Common Ground Collective, (CGC) thanks for New Orleans City Council, put out a call for you in advance for taking time out of your lives to support as white vigilantes patrolled the streets. come to the Gulf Coast region to contribute your Two friends from Austin heeded the call, and came skills and resources toward the relief and rebuilding to protect Malik’s home in Algiers. Sitting around effort. the kitchen Malik, his partner Sharon and Scott Crow from Austin, looked at the devastation around Volunteers play a central role in Common Ground’s them, and put out a call for more help. With $50 work. This handbook will explain Common among them, Common Ground was born. -

AAHP 387 Malik Rahim African American History Project (AAHP) Interviewed by Justin Hosbey and Brittany King on August 6, 2015 1 Hour, 19 Minutes | 30 Pages

Joel Buchanan Archive of African American History: http://ufdc.ufl.edu/ohfb Samuel Proctor Oral History Program College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Program Director: Dr. Paul Ortiz 241 Pugh Hall PO Box 115215 Gainesville, FL 32611 (352) 392-7168 https://oral.history.ufl.edu AAHP 387 Malik Rahim African American History Project (AAHP) Interviewed by Justin Hosbey and Brittany King on August 6, 2015 1 hour, 19 minutes | 30 pages Abstract: Mr. Malik Rahim in this interview discusses his life experiences and family history in New Orleans, Louisiana. He shares the racism his family faced and the resilience they built together. He joined the Navy and traveled to California. There, he became a part of the Black Panther Party and got involved with them back in New Orleans. He discusses the role the Panther Party played in building up the Black community in New Orleans. He shares about the violence from the police and prison system. He concludes the interview delving into the impact of Hurricane Katrina on the community. Keywords: [New Orleans, Louisiana; Black Panther Party; Hurricane Katrina; African American History] Standards: SS.8.A.1.7 View historic events through the eyes of those who were there as shown in their art, writings, music, and artifacts, SS.912.A.7.5 Compare nonviolent and violent approaches utilized by groups (African Americans, women, Native Americans, Hispanics) to achieve civil rights, SS.912.A.7.6 Assess key figures and organizations in shaping the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power Movement, SS.912.C.2.2 Evaluate the importance of political participation and civic participation. -

Dean Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute

May 2019 Dean Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute About Us News Did You Know? Reading Assignment Announcements Contact Us About Us Vision Mission The Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute The Louis A. Berry Institute for Civil Rights seeks to ensure the law center’s place as a center of and Justice is committed to the advancement excellence in social and restorative justice and civil and of civil and human rights and social and restor- human rights research, advocacy, education and in- ative justice, especially in Louisiana and the struction. It further seeks to pursue policy initiatives and South. judicial outcomes that promote equal rights and justice. News Distinguished Lawyer-Leader Lectures SULC Civil Rights Litigation Students and Others Upon completion of the assigned chapters on damages and attorney's fees in her Civil Rights Litigation class, Professor Bell went in search of a practitioner who could complement these theoretical discussions. One attorney impressively emerged from the pool of options. This lawyer, who has served as both a prose- cutor and a judge, has secured hundreds of millions for his clients in some of the largest verdicts in the state. He won his first million dollar case just five years after passing the bar. In 2018, he won three cases that netted more than $81 million in settlements and verdicts. Not only is Tony Clayton the best at what he does, he is also an alumnus of this law center and he is a member of the Southern University System Board of Supervisors. His April 3, 2019 presentation did not disappoint. -

Dean Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute

April 2019 Dean Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute About Us News Did You Know? Prior Events Reading Assignment Announcements Contact Us About Us Vision Mission The Louis A. Berry Civil Rights and Justice Institute The Louis A. Berry Institute for Civil Rights seeks to ensure the law center’s place as a center of and Justice is committed to the advancement excellence in social and restorative justice and civil and of civil and human rights and social and restor- human rights research, advocacy, education and in- ative justice, especially in Louisiana and the struction. It further seeks to pursue policy initiatives and South. judicial outcomes that promote equal rights and justice. News When the Students Became the Teachers: Roots Camp 2019 Civil Rights & Justice Panels The students enrolled in Professor Bell’s Civil Rights Litigation class are taught through a combination of lec- tures and restorative justice projects. This month, they were the experts who taught those in attendance at RootsCamp 2019. There were a total of five restorative justice projects presented over the course of the two-day conference. The Lemon Howard Team Hayden Carlos and Cameron Pontiff discussed their efforts on behalf of the late Lemon Howard. Mr. Howard was an indigent man who, in 1962, was charged with murder. Oddly, Mr. Howard was not convicted of the murder. Instead, he was involuntarily com- mitted to a mental hospital for schizophrenia and, while there, was charged with the murder of a patient. For that crime, he was sentenced to prison. This team unearthed a cosmic size piece of penal history in the form of Dr. -

CCR Annual Report 2012

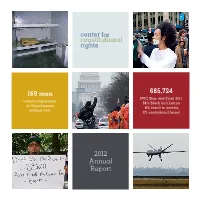

169 men 685,724 NYC Stop and Frisk 2011 remain imprisoned 84% Black and Latino at Guantánamo 6% result in arrests without trial 2% contraband found 2012 Annual Report The Center for Constitutional Rights is dedicated to advancing and protecting the rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Founded in 1966 by attorneys who represented civil rights movements in the South, CCR is a non-profit legal and educational organization committed to the creative use of law as a positive force for social change. www.CCRjustice.org table of contents Letter from the Executive Director ........................................................................................ 2 Guantánamo .............................................................................................................................. 4 International Human Rights ................................................................................................... 8 Government Misconduct and Racial Injustice ................................................................ 12 Movement Support .................................................................................................................. 16 Social Justice Institute ........................................................................................................... 18 Communications .................................................................................................................... 20 Letter from the Legal Director ............................................................................................. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Exit the Matrix, Enter the System: Capitalizing on Black Culture to Create and Sustain Community Institutions in Post-Katrina New Orleans. by Ronni Brooks Armstead/Fari Nzinga Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Bayo Holsey ___________________________ Valerie Lambert ___________________________ Richard J. Powell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2013 ABSTRACT Exit the matrix, Enter the System: Capitalizing on Black Culture to Create and Sustain Community Institutions in post-Katrina New Orleans. by Ronni Brooks Armstead/Fari Nzinga Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Bayo Holsey ___________________________ Valerie Lambert ___________________________ Richard J. Powell An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2013 Copyright by Ronni Brooks Armstead/Fari Nzinga 2013 Abstract After the devastation wrought by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in the Fall of 2005, millions of dollars of