The Architecture of Distributed Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: CECILIA BONN American Academy of Arts and Letters Cecilia Bonn Marketing and Communications 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 (212) 734-9754 / [email protected] THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS ANNOUNCES NEWLY ELECTED MEMBERS AND AWARD WINNERS New York, NY, April 14, 2009 – The American Academy of Arts and Letters will hold its annual induction and award ceremony on Wednesday, May 20, 2009. J. D. McClatchy, president of the Academy, will conduct the presentation of more than fifty awards in architecture, art, literature, and music (see complete list of award winners below). On behalf of the Academy, President McClatchy stated, “The Academy is proud to welcome to its ranks these distinguished new members. It’s an eclectic group of exceptional individuals—each a pioneer of the imagination and an artist of resplendent gifts and achievements.” Secretary of the Academy, Rosanna Warren, will induct nine members into the 250-person organization: artist Judy Pfaff and architect Tod Williams; writers T. Coraghessan Boyle, Jorie Graham, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Richard Price; composers Stephen Hartke, Frederic Rzewski, and Augusta Read Thomas. Academician Louise Glück will deliver the Blashfield Foundation Address, titled “American Originality.” An exhibition of art, architecture, books, and manuscripts by new members and recipients of awards will be on view at the Academy’s galleries from May 21 to June 14, 2009. Newly Elected Members of the Academy Art JUDY PFAFF TOD WILLIAMS Judy Pfaff Tod Williams T. Coraghessan Boyle Literature T . CORAGHESSAN BOYLE JORIE GRAHAM YUSEF KOMUNYAKAA RICHARD PRICE Jorie Graham Yusef Komunyakaa Richard Price Music STEPHEN HARTKE FREDERIC RZEWSKI AUGUSTA READ THOMAS Stephen Hartke Frederic Rzewski Augusta Read Thomas Newly Elected Members of the Academy Writer T. -

Industry Advisory Group Annual Meeting

INDUSTRY ADVISORY GROUP ANNUAL MEETING APRIL 8, 2014 AGENDA AGENDA AGENDA 10:00 - 10:15 AM OPENING REMARKS Lydia Muniz OBO DIRECTOR 10:15 - 10:20 AM OBO YEAR-IN-REVIEW VIDEO 10:20 - 10:45 AM IAG READOUT Sheila Kennedy IAG MEMBER 10:45 - 11:30 AM KEYNOTE Lead Designers Tod Williams & Billie Tsien Discuss the New U.S. Embassy Project in Mexico City, Mexico In 2012, the joint venture, Tod Williams Billie Tsien / Davis Brody Bond Architects, was awarded the commission to design the New U.S. Embassy Complex in Mexico City. Tod Williams and Billie Tsien founded their firm in 1986. Their studio, located in New York City, focuses on work for institutions - museums, schools and non-profits; organizations that value issues of aspiration and meaning, timelessness and beauty. The buildings are carefully made and useful in ways that speak to both efficiency and the spirit. A sense of rootedness, light, texture, detail, and most of all experience are at the heart of what they build. Their compelling body of work includes the Natatorium at the Cranbrook School, the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center, the Asia Society Center in Hong Kong, the Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago, the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and the new LeFrak Center in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Parallel to their practice, Williams and Tsien maintain active teaching careers and lecture worldwide. 11:30 - 11:45 AM Q&A 11:45 AM - 12:00 PM DISCUSSION: THE YEAR AHEAD 12:00 - 12:30 PM NETWORKING SESSION EXHIBIT HALL -

American Academy of Arts and Letters Cecilia Bonn Marketing and Communications 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 (212) 734-9754 / [email protected]

NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: CECILIA BONN American Academy of Arts and Letters Cecilia Bonn Marketing and Communications 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 (212) 734-9754 / [email protected] THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS ANNOUNCES NEWLY ELECTED MEMBERS AND AWARD WINNERS New York, NY, April 14, 2009 – The American Academy of Arts and Letters will hold its annual induction and award ceremony on Wednesday, May 20, 2009. J. D. McClatchy, president of the Academy, will conduct the presentation of more than fifty awards in architecture, art, literature, and music (see complete list of award winners below). On behalf of the Academy, President McClatchy stated, “The Academy is proud to welcome to its ranks these distinguished new members. It’s an eclectic group of exceptional individuals—each a pioneer of the imagination and an artist of resplendent gifts and achievements.” Secretary of the Academy, Rosanna Warren, will induct nine members into the 250-person organization: artist Judy Pfaff and architect Tod Williams; writers T. Coraghessan Boyle, Jorie Graham, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Richard Price; composers Stephen Hartke, Frederic Rzewski, and Augusta Read Thomas. Academician Louise Glück will deliver the Blashfield Foundation Address, titled “American Originality.” An exhibition of art, architecture, books, and manuscripts by new members and recipients of awards will be on view at the Academy’s galleries from May 21 to June 14, 2009. Newly Elected Members of the Academy Art JUDY PFAFF TOD WILLIAMS Judy Pfaff Tod Williams T. Coraghessan Boyle Literature T . CORAGHESSAN BOYLE JORIE GRAHAM YUSEF KOMUNYAKAA RICHARD PRICE Jorie Graham Yusef Komunyakaa Richard Price Music STEPHEN HARTKE FREDERIC RZEWSKI AUGUSTA READ THOMAS Stephen Hartke Frederic Rzewski Augusta Read Thomas Newly Elected Members of the Academy Writer T. -

Itright to Architecture

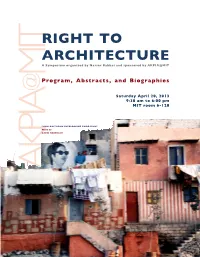

RIGHT TO ARCHITECTURE A Symposium organized by Nasser Rabbat and sponsored by AKPIA@MIT MIT Program, Abstracts, and Biographies @ Saturday April 20, 2013 9:30 am to 6:00 pm MIT room 6-120 “UMM-KALTHOUM OVERLOOKING CAIRO SLUM” Photo by DAVID HABERLAH AKPIA BIOGRAPHIES AND ABSTRACTS ______________________________________________________________ IS THERE A RIGHT TO ARCHITECTURE? Thomas Fisher Dean, College of Design, University of Minnesota ABSTRACT Is there a right to architecture? There is a universal right to shelter, as there is to every- thing else on the first two levels of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (food, water, warmth, security, stability, freedom from fear). But to claim a “right” to “architecture,” we need to qualify what we mean. If we mean by “architecture,” environments that enhance people’s sense of belonging (Maslow’s third level), their self-esteem (fourth level), and self-actualization (fifth level), and if we mean by “right,” an equal opportunity to meet these fundamental needs, then the answer to the opening question is “yes.” But if we mean by “ar- chitecture,” the artistic practice of professional architects, and by “right,” the guarantee of something, then no, people do not have a right to architecture. Indeed, given the provoca- tions that sometimes arise from self-actualized architects’ own creative expression through their buildings, it might be more the case that people have a right not to have to endure such architecture. Accordingly, the question of whether people have a right to architecture demands that, if we are to answer it in the affirmative, architects must attend much more to the hierarchy of other’s needs and much less to their own. -

Download the Report Here

Modern Architecture on the Upper East Side: Landmarks of the Future Presented by FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts September 20, 2001 - January 26, 2002 On view at the New York School of Interior Design 170 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021 Ga ll ery Hours: Tuesday through Saturday, 10:00 a.m. - 5:00 p. m. INTRODUCTION The Upper East Side, stretch ing from East 59th Street to East the 1970s, to more current approaches to architectural design. 96th Street and from the East River to Fifth Avenue, is best We have in cluded private homes, apartment buildings, theaters, known for its historic buildings. The area's mansions, townhouses, and institutional and public buildings, designed by little-known and apartment buildings were erected for some of New York City's architects as we l I as some of the masters of our era. wea lthiest and most prominent resi den ts, and its tenements hou sed There is an urgent need to appreciate and protect our modern tens of thousands of immig rants. These hi storic buildings form architectural heritage. Even as we planned this exhibition, the the core of the neighborhood and are rightly a source of pride facade of one of the buildings we intended to feature- the and interest. But the Upper East Side also boasts a surprisingly private residence at 525 East 85th Street designed by Paul Jean large number of outstanding modern structures. Mitarachi in 1958-was removed. While none of the buildings With this exhibition, we hope to promote a greater apprecia in the exhibition are designated New York City landmarks, fifteen tion and understanding of modern architecture on the Upper East of the twenty-two structures chosen are more than thirty years old Side by highlighting distinguished modern buildings located out and therefore could be considered for landmark designation.