Online Literature & Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Brian McWhorter associate professor of music University of Oregon Curriculum Vitae Current Academic Position University of Oregon Associate Professor of Music 2006- Other Positions Eugene Ballet Company Music Director 2017- Orchestra Next Music Director 2012- Orchestra Next Executive Director 2012- Previous Teaching Positions Manhattan School of Music Professor of Contemporary Music 2007-10 Louisiana State University Assistant Professor of Trumpet and Jazz Studies 2004-06 East Carolina University Robert L. Jones Distinguished Visiting Professor 2004-05 Princeton University Trumpet Teacher 2001-04 Kinhaven Summer Music School Trumpet / Chamber Music Teacher 2003-07 Greenwich House Music School Brass Teacher 1999-04 The Juilliard School Teaching Assistant - Music Technology 2000 Education The Juilliard School Master of Music in Trumpet Performance 2000 student of Raymond Mase Aspen Music Festival and School Fellowship Student 2000 student of Kevin Cobb University of Oregon Bachelor of Music in Trumpet Performance 1998 student of George Recker Aspen Music Festival and School Scholarship Student 1997 student of Chris Gekker Aristoxenos Summer Music School Performance Certificate 1996 student of Anthony Plog McWhorter 1 Research Affiliations Composers of Oregon Chamber Orch. guest conductor 2018 Anchorage Symphony guest conductor 2014- I Live for Art documentary featuring my work throughout 2014 Orchestra NEXT music director, conductor and founder 2012- Mark Gould & Pink Baby Monster composer and performer 2001- Beta Collide co-artistic director -

Shot to Death at the Loft

SATURDAY • JUNE 12, 2004 Including The Bensonhurst Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages • Vol. 27, No. 24 BRZ • Saturday, June 19, 2004 • FREE Shot to death at The Loft By Jotham Sederstrom Police say the June 12 shooting happened in a basement bathroom The Brooklyn Papers about an hour before the bar was to close. Around 3 am, an unidentified man pumped at least four shots into A man was shot to death early Saturday morning in the bath- Valdes, who served five years in prison after an arrest for robbery in room of the Loft nightclub on Third Avenue in Bay Ridge. 1989, according to Kings County court records. The gunman, who has Mango / Greg Residents within earshot of the club at 91st Street expressed concern thus far eluded police, may have slipped out the front door after climb- but not surprise at the 3 am murder of Luis Valdes, a Sunset Park ex- ing the stairs from the basement, say police. convict. Following the murder, Councilman Vincent Gentile voiced renewed “That stinkin’ place on the corner,” said Ray Rodland, who has lived support for legislation that would allow off-duty police officers to moon- on 91st Street between Second and Third avenues for 20 years. “Even light as bouncers — in uniform — at bars and restaurants. The bill is Papers The Brooklyn if you’re farther away, at 4 in the morning that boom-boom music currently stalled in a City Council subcommittee for public housing. -

An Intelligent Technique to Customise Music Programmes for Their Audience

Poolcasting: an intelligent technique to customise music programmes for their audience Claudio Baccigalupo Tesi doctoral del progama de Doctorat en Informatica` Institut d’Investigacio¶ en Intel·ligencia` Artificial (IIIA-CSIC) Dirigit per Enric Plaza Departament de Ciencies` de la Computacio¶ Universitat Autonoma` de Barcelona Bellaterra, novembre de 2009 Abstract Poolcasting is an intelligent technique to customise musical se- quences for groups of listeners. Poolcasting acts like a disc jockey, determining and delivering songs that satisfy its audience. Satisfying an entire audience is not an easy task, especially when members of the group have heterogeneous preferences and can join and leave the group at different times. The approach of poolcasting consists in selecting songs iteratively, in real time, favouring those members who are less satisfied by the previous songs played. Poolcasting additionally ensures that the played sequence does not repeat the same songs or artists closely and that pairs of consecutive songs ‘flow’ well one after the other, in a musical sense. Good disc jockeys know from expertise which songs sound well in sequence; poolcasting obtains this knowledge from the analysis of playlists shared on the Web. The more two songs occur closely in playlists, the more poolcasting considers two songs as associated, in accordance with the human experiences expressed through playlists. Combining this knowl- edge and the music profiles of the listeners, poolcasting autonomously generates sequences that are varied, musically smooth and fairly adapted for a particular audience. A natural application for poolcasting is automating radio pro- grammes. Many online radios broadcast on each channel a random sequence of songs that is not affected by who is listening. -

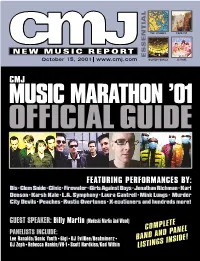

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Bringing Moshiach Values Into Our Homes

11 Tammuz 5780 Bringing Moshiach Values July 3 2020 Into Our Homes Price: $4.95 no. 1219 יחי אדוננו מורנו ורבינו מלך המשיח לעולם ועד shabbos י“ב תמוז 07/04 Candle lighting Sunrise Latest shema Midday Sunset Shabbos ends 8:12 5:30 9:15 1:00 8:29 9:20 ג' פרקים: הלכות אבל פרקים ט-יא. פרק אחד: הלכות מלכים ומלחמותיהם פרק ז. ספר המצוות: מל״ת קסו Sunday Monday י“ד תמוז 07/06 י“ג תמוז I’m Sure It Will Be Fulfilled” 07/05“ Sunrise Latest shema Sunset Sunrise Latest shema Sunset Mrs. Fruma Ita Simpson, was the wife of Rabbi Eliyahu Yaichel (Simpson). 5:31 9:15 8:29 5:31 9:16 8:29 She and her family enjoyed and merited to have a very special connection with ג' פרקים . הלכות מלכים ומלחמותיהם פרקים א-ג ג' פרקים . הלכות אבל פרקים יב-יד פרק אחד . הלכות מלכים ומלחמותיהם פרק ט פרק אחד . הלכות מלכים ומלחמותיהם פרק ח Beis HaRav — the Rebbe and his family. Her son, Rabbi Sholom Mendel, was ס' המצוות . מ״ע קעג. מל״ת שסב. שסד. שסג. שסה ס' המצוות . מל״ת קסו .one of the Rebbe’s secretaries Once, he wrote a letter regarding his mother’s health, and that the family requests a “bracha that very soon the Rebbe shlita’s bracha should be fulfilled.” In response, the Rebbe wrote: Tuesday Wednesday ט“ז תמוז 07/08 ט“ו תמוז 07/07 Sunrise Latest shema Sunset Sunrise Latest shema Sunset 5:32 9:16 8:29 5:32 9:16 8:28 ג' פרקים . -

![Journal of the Short Story in English, 36 | Spring 2001 [Online], Online Since 13 June 2008, Connection on 03 December 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6170/journal-of-the-short-story-in-english-36-spring-2001-online-online-since-13-june-2008-connection-on-03-december-2020-1856170.webp)

Journal of the Short Story in English, 36 | Spring 2001 [Online], Online Since 13 June 2008, Connection on 03 December 2020

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 36 | Spring 2001 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/107 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2001 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Journal of the Short Story in English, 36 | Spring 2001 [Online], Online since 13 June 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/107 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Melville’s Wall Street: It Speaks for Itself Matthew Guillen Preferring not to:The Paradox of Passive Resistance in Herman Melville’s “Bartleby” Jane Desmarais James Joyce’s “A Little Cloud” and Chandler’s Tears of Remorse Mary Lazar The fragment, the spiral and the network: the progress of interpretation in Louise Erdrich’s “American horse” Isabelle Thibaudeau-Pacouïl The narrator in Neil Jordan's short stories Maguy Pernot-Deschamps Journal of the Short Story in English, 36 | Spring 2001 2 Melville’s Wall Street: It Speaks for Itself Matthew Guillen 1 Subtitled “A Story of Wall Street”, Herman Melville’s compact and—compared to its controversial immediate predecessor Pierre or the Ambiguities—“tidy” piece, “Bartleby the Scrivener” evokes an insular, and cartographically almost peninsular, portion of Manhattan Island shimmering in the newly emerging largesse which will soon typify New York as the grand commercial crossroads of the world.1 2 The tale involves the relationship between Bartleby and his employer, the attorney narrator, and unfolds within office spaces only explicitly defined by two windows facing exterior walls as well as by a wooden screen and a folding panel with panes of ground glass—the former separating Bartleby from the lawyer and the latter effectively separating the lawyer and Bartleby from Turkey, Nippers, and Ginger Nut, the other characters in the lawyer’s employ. -

Ind New )Ersonal

THE ALL DAY 0 MUSIC STATION =eatu ri ng he TOP Z DEE JAYS Ind new M )ersonal o stories of rz he STARS O o zi iW o WIN YOUR FAVOURITE z L.P'S. N I N OUR EXCITING CONTEST www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com The famous Ships ... the Stars ... the deejays ... the lot! It's right here for you in the first ever book on the nation's first ever commercial radio network. Copyright © MCMLXV by RADIO CAROLINE, SPECTRE PROMOTIONS LIMITED RADIO All rights reserved throughout the world Published in Great Britain by World Distributors (Manchester) Ltd., 12 -14 Lever Street, Manchester 1. CAROLINE Printed in Great Britain by Fletcher Er Son Ltd, Norwich ANNUAL EDITED BY PAUL DENVER www.americanradiohistory.com Vitt 1 CONTENTS OW 7 CAROLINE CALLING Exactly six months after going on Just why has Radio Caroline This book takes you behind NON -STOP TO STARDOM the air with its No 1 broadcast, become a "must" listening -post the scenes of the two famous HOW HIGH THE BOOM? Radio Caroline's first how -they- for millions? One major answer broadcasting ships. So step right listen survey came up with the is the friendly informality - and in and see how it all ticks, meet WHY THEY DON'T GO BACK news that the two ships were brevity - of Radio Caroline's bril- the men who run the whole WHAT'S IN A NAME? winning the battle of the sound liant deejays. show, sit in on a broadcasting waves at the speed of an Olympic A 20- year -old girl put it to me session - and, for good measure, I LIKE champion. -

SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist 941 Songs, 2.5 Days, 3.39 GB

Page 1 of 27 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist 941 songs, 2.5 days, 3.39 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 DONT LET ME DOWN 3:25 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist A.J. Croce 2 Another Seven Years 3:59 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Aberdeen City 3 Drive Away Slow 4:30 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Abi Tapia 4 Sometimes 2:52 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Abigail Washburn 5 THE GAME 3:18 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Action Action 6 Voodoo Economics 3:50 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Ad Astra Per Aspera 7 Tell Me, Tell Me 2:35 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist The Adored 8 My Love Will Keep 4:19 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Adrienne Young & Little Sadie 9 Buildings 3:43 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Adult Rodeo 10 This is my love 3:37 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist The Aeroplanes 11 Craked Teeth 2:41 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Ahleuchatistas 12 Rockness Monster 3:09 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Akimbo 13 World Came Tumbling Down 3:36 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Al Anderson 14 I Am the Lazer Viking 0:45 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist An Albatross 15 WHAT I FEEL IS MINE 2:59 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Alien Ant Farm 16 Playing the Game 3:28 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist AM 17 All My Wasted Days 3:44 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist The Amazing Pilots 18 Gone So Young 3:24 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Amber Pacific 19 Seconds Until Midnight 3:40 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist Ambulette (aka Bella lea) 20 Radio 3:33 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist American Eyes 21 Buffalo Creek 3:39 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist American Minor 22 Stolen Blues 2:32 SXSW 2006 Showcasing Artist American Princes 23 Colors -

28/48 Bwn/Awp

P3 P6 P9 Nets P4 THE BROOKLYN SMART NOTHIN’BUT drop two By Gersh Bright ideas ETS more ANGLE Kuntzman mom A holiday gift guide N games BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages BRZ •Vol. 28, No. 48 • Saturday, December 10, 2005 • FREE PAGE 7 THE SURVEY SAYS... BORO’S BIZ Andy Sachs FEARS 2006 The Fort Hamilton Tigers celebrate their championship. By Gersh Kuntzman • Nearly 70 percent of businesses believe they The Brooklyn Papers will hire new employees next year. Un-happy New Year! • The city needs to do a better job in Brooklyn. That will be the cheer of many Brooklyn busi- Nearly 80 percent cited poor streets conditions as a nesses as the clock strikes midnight on Jan. 1, 2006, problem. Litter was a concern of 64 percent. according to a just-released report by the borough’s • Amajority — but not a strong majority — be- lieves the city school system is moving in the right Tigers Chamber of Commerce. Only 31 percent of business owners believe they direction. The 53 percent who said the school system will have a good year in 2006 — a marked contrast is getting better is a jump from only 40 percent who to the 80 percent of companies that expected good answered that way last year. things as they went into 2005. • Only 18 percent of business owners oppose Roughly 55 percent think 2006 will be worse or Bruce Ratner’s plans for a 24-acre commercial, resi- about the same as 2005. -

Cjre €0% €T\A, Eitep&Py

Cjre €0% €t\a, Eitep&py. Published every other Week during the Collegiate THE MINISTRY. Year by the Students of COLBY UNIVERSITY. The opportunities which the Christian ministry offers to a conscientious, Christian ' EDITORIAL BOARD. man are of two kinds ; to secure his own Chief. welfare and to serve his fellbwmen. Of the C. H. Whitman, 97. first sort are those for his material arid so- Assistant Chief. cial life and those for his intellectual and Miss Edith B. Hanson, '97. spiritual life. To the first of these no man should give much thought. He who can, Department Staff. lacks something of the ChristianV spirit. T. R. Pierce, '98, Bill Board . M/ss E. S, Nklson, '97, Personals and Bill Board But if any. man is fostering . his spiritual A. H. Page, '98, . Y, M. C. A pride with the thought that lie is sacrific- Miss Lenora Bessey, '98, Alumna and Y. W. C. A, ing material and social comforts , by enter- I. F. Ingraham, '98, Exchanges N. K. Fuller, '98, Alumni ing the ministry, he may be reminded that J. L. Dyer, '98, Personals , probably no profession offers its members Business Manager, so high ah average of material and social W. A. Harthorne, ' 97. , advantages as the ministry. Jhdeed so Treasurer. great are the temptations in this profession ' C. L. Snow, '97. to practise the arts of oratory for the sake of fame, to seek for relatively high salaries, Terms.—$1,50 Per year. ' Single copies 12 cents. fine housing, special favors from, the "de- Tub Echo will be sent to nil subscribers, until its discontinuance is ordered, and arrears paid. -

And Law Enforcement Crimes Against Animals Are Crimes Against People

&DEPUTY 2019 Special Issue: Animal Cruelty THE “LINK” AND LAW ENFORCEMENT CRIMES AGAINST ANIMALS ARE CRIMES AGAINST PEOPLE SHERIFFS.ORG/NLECAA ALSO INSIDE: The Day America Realized There is a Big Cat Crisis ................. pg10 Evidence in Animal Cruelty Cases: What Prosecutors Want ..... pg14 A Dog in the Closet ............. pg20 Saddled with the Bill: Restitution for Seized Animals’ Costs of Care .................................... pg23 THE “LINK” AND LAW ENFORCEMENT: CRIMES AGAINST ANIMALS ARE CRIMES AGAINST PEOPLE 6 Cover image by Virgil Ocampo for Show Your Soft Side CONTENT 3 Crimes Against Animals Are Crimes 20 A Dog in the Closet 30 Investigating Hypothermia in Against Our Communities By Jill Hollander Dogs: A Guide for Law Enforcement By Sheriff John Layton Provided by the Humane Society of the 21 Healing Together: United States 4 The Changing Landscape of Sheltering Survivors of Domestic Animal Cruelty Violence with Their Pets 32 The Law Enforcement Guide: By John Thompson By Andrew M. Campbell What You Should Know About Bestiality 9 Training Police Officers 23 Saddled with the Bill: Restitution By M. Jenny Edwards to Identify Animal Cruelty Crimes for Seized Animals’ Cost of Care By Kitty Block By Kathleen Wood, Esq. 36 Best Practices in Animal Cruelty Investigations 10 The Day America Realized 26 From the Backyard to the By April Doherty and Martha Smith- There is a Big Cat Crisis Football Field: How Michael Vick Blackmore By Sheriff Matthew Lutz and Jennifer Leon Brought Animal Fighting to the Forefront and Why Law Enforcement 38 Law Enforcement Encounters 12 NIBRS Needs Both Law Should Care with Dogs Enforcement and Animal By Chelsea Rider By Jim Crosby Control Officers By Mary Lou Randour, Ph.D. -

29/25 Awp/Bwn

MARKOWITZ OK AFTER HEART SCARE • HOW MARTY’S DIET CAN SAVE YOUR LIFE P6 BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Paper and the Downtown News Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2006 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20 pages •Vol.29, No. 25 AWP • Saturday, June 24, 2006 • FREE RATNER’S SHADOW LOOMS Pratt study: Atlantic Yards would put Fort Greene in darkness By Gersh Kuntzman Atlantic Yards The Brooklyn Papers ‘does not work’ Bruce Ratner has been accused of many things, but WORST now he’s being accused of PAGE 16 stealing the sun from the sky. According to a new analysis by a Pratt Institute professor and two students, shadows from the developer’s Atlantic START Yards mega-project would darken a wide swath of Brook- lyn from Prospect Heights to Downtown — including a strip in Fort Greene that won the “Greenest Block in Brook- EVER! lyn” contest in 2002. At its worst — at 9 am on Dec. 21 — the shadow from the 62-story “Miss Brooklyn” building, proposed for the cor- Yanks crush ner of Atlantic and Flatbush av- enues, would extend all the way to Fulton and Gold streets. “Shadows from September Clones 18-0 to March will be severe,” said Brent Porter, the Pratt profes- By Vince DiMiceli sor. “Once those buildings go up, the shadowing will be for- The Brooklyn Papers ever.” The Brooklyn Cyclones sixth home TRIPLE-THREAT Porter said he and his stu- The Christina Porter Memorial Lighting Lab, Pratt Institute; Roman Strazhko Architect; Porter, Brent Prof.