Taking Umpiring Seriously: How Philosophy Can Help Umpires Make the Right Calls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1962-04-20

Traflie Accident Kills Another SUI Student A traffic accident Wednesday Listed in very good condition All three students were resi The death was Johnson Coun which she was riding crashed night took the life of the third at Student Health Infirmary dents of Quadrangle Dormitory. ty's sixth traffic fatality this into a tree on Bowery street. SUI sludent to be killed in auto Thursday were Rodney Reimer, Highway Patrolman Howard The 1961 Corvette was driven by AI, Granville, driver of the car Shapcott said the three students year - three oC them occuring Allen Bower, A4, Glen Ellyn, accidents in four days. this week. Marvin Kent Peterson, AI, and John Szaton, AI, Tinley were thrown from Reinmer's 111. Dayton, was fatally injured at Park, Ill. Reimer suffered mUl 1955 model ear. Peterson was Eleanor FirzlafC, A4, Dubuque, Another SUI sludent, Kenneth 11:30 p.m. when the car in which tiple bruises and Szaton was taken to University Hospitals, died Monday morning at Univer Quirk, At, Alla, died Tuesday he was riding missed a curve treated for scalp cuts and where he died at 12:35 a.m. o( sity Hospitals oC injuries received night after a car crashed into and overturned in a shallow bruises. a ruptured liver and spleen. in an automobile accident Sun the back of II molar scooter on ditch Hi miles south of North Both may be released from the Charges against Reimer are day night. Miss FirzlafC suffered which he was riding on Highway Liberty. Infirmary today. pending. head injuries when the car in 6 in Coralville. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

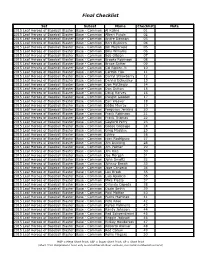

Final Checklist

Final Checklist Set Subset Name Checklist Note 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Al Kaline 01 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Albert Pujols 02 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Andre Dawson 03 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bert Blyleven 04 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bill Mazeroski 05 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Billy Williams 06 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bob Gibson 07 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Brooks Robinson 08 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bruce Sutter 09 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Cal Ripken Jr. 10 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Carlton Fisk 11 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Darryl Strawberry 12 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dennis Eckersley 13 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Mattingly 14 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Sutton 15 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Doug Harvey 16 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dwight Gooden 17 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Earl Weaver 18 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Eddie Murray 19 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Ferguson Jenkins 20 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Robinson 21 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Thomas 22 2015 Leaf Heroes of -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

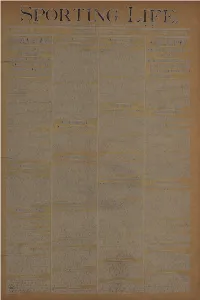

This Entire Document

SPORTINGTBADXXAXKED BY THB SFOKTINO LIFE PVB. CO. SNTBSBD AT PHILA. P. O. ASLIFE. SECOND CLASS MATTBB VOLUME 25, NO. 21. PHILADELPHIA, AUGUST 17, 1895. PKICE, TEN CENTS. BRDSH WELL PLEASED MANAGERIAL YIEWS A BIG CUT-DOWN. LATE NEWS BY WIRE. With the Financial Results of This On Mr. Byrne's Position In the Campaign. Temple Cup Matter. Special to "Snorting Life." Special to "Sporting Life." FROM EIGHT CLUBS TO FOUR AT THE O'CONNOR SUIT AGAIHST THE Cincinnati, Aug. 16. The Cincinnati Club Baltimore, Aug. 10. While the Bostons las made more money so far this season were here both Managers Selee and Han- LEAGDE FIZZLES OPT. han any year since the formation of the on talked over the Temple Cup question. ONE SWOOP. resent 12-olub circuit. "Cincinnati is uot Mr. Selee agreed with Ha u Ion that the In- he only city that has done well," said Pres- entlon of the giver of the cup was that dent Brush. "Every city In the League has t should be played for each season by the The Texas-Southern League Loses San Tne California Winter Trip is Assured njoyed increased attendance, and there is rst and second clubs, but Mr. Byrne, who very propspect that it will continue until 9 a member of the Temple Cup Committee, Managerial Views o! the Temple he end of the season. An Improvement in hlnks the club winning the championship Antonio, Honston and Shreveport, he times, together with an increased In- hould play New York for the trophy. The erest In the game by reason of the close Boston manager suggested that as a com- Oasts Austin and Reorganizes as a Cnp Question A Magnate's Optim and exciting race are the causes of this >romise the first and second clubs play a >rosperity." Mr. -

Kit Young's Sale #154

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #154 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALLS 500 Home Run Club 3000 Hit Club 300 Win Club Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball (16 signatures) (18 signatures) (11 signatures) Rare ball includes Mickey Mantle, Ted Great names! Includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Eddie Murray, Craig Biggio, Scarce Ball. Includes Roger Clemens, Williams, Barry Bonds, Willie McCovey, Randy Johnson, Early Wynn, Nolan Ryan, Frank Robinson, Mike Schmidt, Jim Hank Aaron, Rod Carew, Paul Molitor, Rickey Henderson, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Thome, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson, Warren Spahn, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton Eddie Murray, Frank Thomas, Rafael Wade Boggs, Tony Gwynn, Robin Yount, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Dave Winfield, and Greg Maddux. Letter of authenticity Palmeiro, Harmon Killebrew, Ernie Banks, from JSA. Nice Condition $895.00 Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. Letter of Cal Ripken, Al Kaline and George Brett. authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1895.00 Letter of authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1495.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (All balls grade EX-MT/NR-MT) Authentication company shown. 1. Johnny Bench (PSA/DNA) .........................................$99.00 2. Steve Garvey (PSA/DNA) ............................................ 59.95 3. Ben Grieve (Tristar) ..................................................... 21.95 4. Ken Griffey Jr. (Pro Sportsworld) ..............................299.95 5. Bill Madlock (Tristar) .................................................... 34.95 6. Mickey Mantle (Scoreboard, Inc.) ..............................695.00 7. Don Mattingly (PSA/DNA) ...........................................99.00 8. Willie Mays (PSA/DNA) .............................................295.00 9. Pete Rose (PSA/DNA) .................................................99.00 10. Nolan Ryan (Mill Creek Sports) ............................... 199.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (Sold as-is w/no authentication) All Time MLB Records Club 3000 Strike Out Club 11. -

Newberry Major Leaguer Looks Back Th Th Thth

THE NEWBERRY OBSERVER – Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2010 I PAGE 7 55th 55th Newberry major leaguer looks back Leslie Moses Staff Writer t still seems like a dream, says New- Iberry’s Billy O’Dell of his nearly 14-year major league baseball career. But 55 years ago, O’Dell stepped from the Clemson campus as an All-American into the big leagues in Baltimore. “June 8, 1954,” says O’Dell, 77. “That’s one of those things you never for- —Staff photo by get. That was the Leslie Moses beginning of it all.” DIGGER — As a pitcher for Billy O’Dell in Newberry High, O’Dell knew he was a pret- never would be. He was a nice guy,” he says. his living room ty good ballplayer. today. Sometimes 10 scouts watched the strike- O’Dell, too, it seems, out king at his high school ball games. is a nice guy. In one game, the lanky left-hander sat 28 Orioles pitching coach Harry Brecheen Clinton High batters. took him out to dinner right after O’Dell At Clemson, he once sat 21 Gamecock bat- signed with Baltimore for steak and wisdom ters, all of whom returned after the game to to ensure O’Dell stayed on track. shake his hand. “Billy, you’re going to be a good pitcher,” His Clemson team was good, he says, but O’Dell recalls Brecheen saying. “You’re full of graduating seniors. So, as a junior, going to the top. You’re going to pass a lot of figuring the Tigers wouldn’t be as good his players. -

Boys of the Blue Ridge

Swinging for the Fences, and the Kid from Lonaconing 1920 Season - Class D, Blue Ridge League by Mark C. Zeigler CHAPTER 1 POST-WAR BASEBALL The towns surrounding the northern Blue Ridge mountains has had a taste of professional baseball for several years, before the Great World War (known today as World War I) abruptly curtailed the 1918 season just three weeks into the season, and the effects of the deadly Spanish Influenza, and lack of financial support wiped out professional baseball in the region in 1919. Baseball had been strong focal points for the participating communities that organized teams in the Class D, Blue Ridge League. This was a time when the trolley was the main source of transportation, and the vehicle of choice was a Maxwell. Radio was just in its infant stages, and television was not even heard of for almost another twenty years. By 1920, the 20th and 21st amendments allowed women the right to vote, while Prohibition was in full force throughout the country. The nation’s attitudes were changing, but one constant was baseball. People were reenergized after the war effort had ended, and were looking for new things to do in their spare time. Baseball offered them a few hours of distraction from their daily lives, and chance to support their community by “rooting for their home team.” The remnants of the war, and the Spanish Influenza of latter part of 1918 played a significant influence in lack of interest, and financial support of professional baseball in Blue Ridge League towns of Cumberland, Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland, Martinsburg, West Virginia, and the Pennsylvania Townships of Chambersburg, Hanover and Gettysburg in 1919. -

BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 the Game I’Ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams As Told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer Recalls Opening Day Walk-Off Homer

CONTENTS January/February 2016 — Volume 75. No. 1 FEATURES 9 Warmup Tosses by Bob Kuenster Royals Personified Spirit of Winning in 2015 12 2015 All-Star Rookie Team by Mike Berardino MLB’s top first-year players by position 16 Jake Arrieta: Pitcher of the Year by Patrick Mooney Cubs starter raised his performance level with Cy Young season 20 Bryce Harper: Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan MVP year is only the beginning for young star 24 Kris Bryant: Rookie of the Year by Bruce Levine Cubs third baseman displayed impressive all-around talent in debut season 30 Mark Melancon: Reliever of the Year by Tom Singer Pirates closer often made it look easy finishing games 34 Prince Fielder: Comeback Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan Slugger had productive season after serious injury 38 Farewell To Yogi Berra by Marty Appel Yankee legend was more than a Hall of Fame catcher MANNY MACHADO Orioles young third 44 Strikeouts on the Rise by Thom Henninger baseman is among the game’s elite stars, page 52. Despite many changes to the game over the decades, one constant is that strikeouts continue to climb COMING IN BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 The Game I’ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams as told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer recalls Opening Day walk-off homer 52 Another Step To Stardom by Tom Worgo Manny Machado continues to excel 59 Baseball Profile by Rick Sorci Center fielder Adam Jones DEPARTMENTS 4 Baseball Stat Corner 6 The Fans Speak Out 28 Baseball Quick Quiz SportPics Cover Photo Credits by Rich Marazzi Kris Bryant and Carlos Correa 56 Baseball Rules Corner by SportPics 58 Baseball Crossword Puzzle by Larry Humber 60 7th Inning Stretch January/February 2016 3 BASEBALL STAT CORNER 2015 MLB AWARD WINNERS CARLOS CORREA SportPics (Top Five Vote-Getters) ROOKIE OF THE YEAR AWARD AMERICAN LEAGUE Player, Team Pos. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title : author : publisher : isbn10 | asin : print isbn13 : ebook isbn13 : language : subject publication date : lcc : ddc : subject : cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii In the Ballpark The Working Lives of Baseball People George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the netLibrary eBook. © 1998 by the Smithsonian Institution All rights reserved Copy Editor: Jenelle Walthour Production Editors: Jack Kirshbaum and Robert A. Poarch Designer: Kathleen Sims Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gmelch, George. In the ballpark : the working lives of baseball people / George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1-56098-876-2 (alk. paper) 1. BaseballInterviews 2. Baseball fields. 3. Baseball. I. Weiner, J. J. II. Title. GV863.A1G62 1998 796.356'092'273dc21 97-28388 British Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available A paperback reissue (ISBN 1-56098-446-5) of the original cloth edition Manufactured in the United States of America 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 5 4 3 2 1 The Paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z398.48-1984. For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions.