Working Paper 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SASANASIRITISSA THERO and OTHERS V. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D

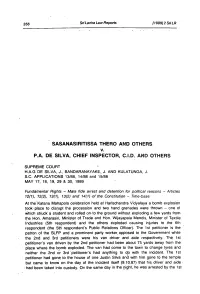

356 Sri Lanka Law Reports (1989) 2 Sri LR SASANASIRITISSA THERO AND OTHERS v. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D. AND OTHERS SUPREME COURT H.A.G DE SILVA, J „ BANDARANAYAKE,. J. AND KULATUNGA, J. S.C. APPLICATIONS 13/88, 14/88 and 15/88 MAY 17, 18, 19, 29 & 30, 1989 Fundamental Rights - Mala tide arrest and detention tor political reasons - Articles 12(1), 12(2), 13(1), 13(2) and 14(1) of the Constitution - Time-base At the Katana Mahapola celebration held at Harischandra Vidyalaya a bomb explosion took place to disrupt the procession and two hand grenades were thrown - one of which struck a student and rolled on to the ground without exploding a few yards from the Hon. Amarasiri, Minister of Trade and Hon. Wijayapala Mendis, Minister of Textile Industries (5th respondent) and the others exploded causing injuries to the 6th respondent (the 5th respondent's Public Relations Officer). The 1st petitioner is the patron of the SLFP and a prominent party worker opposed to the Government while the 2nd. and 3rd petitioners were his van driver and aide respectively. The 1st petitioner’s van driven by the 2nd petitioner had been about 75 yards away from the place where the bomb exploded. The van had come to the town to change tyres and neither the 2nd or 3rd' petitioner's had anything to do with the incident. The 1 st petitioner had gone, to the house of one Justin Silva and with him gone to the temple but came to know on the day of the incident itself (9.10.87) that his driver and aide • had been taken into custody. -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

24079-9781475580303.Pdf

SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS 1984 ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution International Standard Serial Number: ISSN 0074-7025 ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS SEPTEMBER 24-27, 1984 WASHINGTON, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution CONTENTS PAGE Introductory Note xi Address by the President of the United States of America, Ronald Reagan 1 Opening Address by the Chairman of the Boards of Governors, the Governor of the Fund and the Bank for Japan, Noboru Takeshita 8 Presentation of the Thirty-Ninth Annual Report by the Chair- man of the Executive Board and Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, J. de Larosiere 19 Discussion of Fund Policy at Second Joint Session Report by the Chairman of the Interim Committee of the Board of Governors on the International Monetary Sys- tem, Willy De Clercq 30 Statements by the Governors for Ireland—Alan M. Dukes* 35 United States—Donald T. Regan 39 France—Pierre Beregovoy 44 Dominican Republic—Jose Santos Taveras* 48 Korea—Mahn-Je Kim 53 Indonesia—Radius Prawiro 56 Canada—Michael H. Wilson 60 Discussion of Fund Policy at Third Joint Session Statements by the Governors for Italy—Giovanni Goria 67 India—Pranab Kumar Mukherjee 75 United Kingdom—Nigel Lawson 80 Zambia—L.J. Mwananshiku* 90 Germany, Federal Republic of—Gerhard Stoltenberg ... 97 Tunisia—Ismail Khelil* 101 Netherlands—H.O. Ruding 104 Australia—Paul J. Keating 108 Israel—Moshe Y. Mandelbaum Ill Speaking on behalf of a group of countries. -

Gamani Corea: My Memoirs Published by the Gamani Corea Foundation, Vishva Lekha Printers, 2008, PP

Gamani Corea: My Memoirs Published by the Gamani Corea Foundation, Vishva Lekha Printers, 2008, PP. 483 By Saman Kelegama Review Essay The establishment of the S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (SWRD) government opened a new chapter in the planning process in Ceylon. ‘The nationalistic and socialist leaning of Mr. Bandaranaike made him a convinced adherent of the concept of planning’(p.217). What was in doubt was GC’s fate as head of the Planning Secretariat under the Kotalawela government and as the main architect of the Six Year Plan. There had been some rumblings in the Cabinet. However, the new Finance Minister, Stanley de Zoysa who was not subject to political prejudices requested GC to continue, with the concurrence of SWRD. This is an autobiography of a person who participated at the highest centres of policy making at both the national and international levels in the field of development planning and policy. Gamani Corea (GC) wanted to centre his memoirs around his professional life without having a conventional format. Starting work in his memoirs in 1992, he kept writing until he completed them in 2002 when in this very year, he fell ill and could not undertake further work. The Gamani Corea Foundation and a contemporary of GC, Godfrey Gunatilleke put the final touches to the manuscript to bring out this volume. The exercise was funded by Lalith Kotalawela. The Volume is divided into five parts: (1) Growing up; (2) The Years in Cambridge and Oxford; (3) My Career in Sri Lanka; (4) My UNCTAD Days; and (5) Returning Home and After, and covers 483 pages. -

Doctorates a Dime a Dozen Professor Dr

Wednesday 6th December, 2006 7 Appreciation Doctorates a Dime a Dozen Professor Dr. Ariacutty Jayendran I must congratulate “Deep Throat” for themselves Doctor. Did Archimedes, his excellent piece entitled “ Doctorates a Galileo. Isaac Newton, Leonardo Da Vinci, Prof Dr. Ariyacutty Jayendran was tronics and communication engineer- Dime a Dozen- on page 9 of your esteemed Shakespeare., even dream of calling them- one of the prominent physicists pro- ing. In 1959 he obtained a position at newspaper dated 1st December. selves Doctor. Who am I to do so ? duced by Sri Lanka in the first decade Standard Telephone and Cables which It is time we in Sri Lanka took a rational He went on to tell me that when he got following independence. He was a con- had its headquarters in the US and was view regarding the numerous “Doctorates his first Doctorate many years ago and cer- temporary of Professor Charles probably the largest both genuine and fake, both granted by tain newspapers began to call him Doctor, Dahanayake of Kelaniya University Telecommunication Company in the recognised Universities empowered to do he had personally informed all the Editors fame, and the late Professor P. C. B. World to obtain the necessary experi- so and those showered by institutions of all of all newspapers in Sri Lanka to kindly Fernando of Sri Jayewardenapura ence in the industry. Then, in London types not authorised by any law or statute refrain from calling him Doctor, which University, both of whom were pioneers he followed evening classes for a to grant them. As your letter mentions request the newspapers had all followed. -

A Small Step in Burma

10 Friday 15th February, 2008 J R Jayewardene Dr N M Perera Felix Dias Bandaranaike T B Ilangaratne Ronnie de Mel Bandula Gunawardena by Dr Wimal also did not cut a good figure projects with investment goods Member of Parliament, thrash- beginning of the challenges to increased exorbitantly, due to Wickramasinghe while R G Senanayake contin- being made available for pro- ing the then UNP government the Minister of Trade came (a) low harvesting on account of ued as Minister of Trade and duction. In the process, the from 1989 to 1994 on many eco- with the period of Ravi seasonal reasons; (b) devasta- n the past, it was the Commerce under SWRD, until rupee value vis-à-vis the dollar nomic and trade fronts, pretend- Karunanayake, both internally tion of paddy stores and ware- he was removed by Prime depreciated drastically accord- ing that he alone knew the and internationally.Though Minister of Finance who house in the Dry Zone due to Minister W Dahanayake in ing to the vagaries of the world panacea or answers to many there were criticisms against Ibecame the eye-sore of the flooding, (c) manipulation of January 1960. market and the performance of economic ills of the govern- Ravi on items like extravagant public as it was he who had to the price of rice by some large- impose taxes on people to either Although Felix Dias the balance of payments. ment. He is a good Sinhala ora- expenditure, recruitment of scale mill operators who kept a cover the deficit in the budget Bandaranaike took over the Though prices were on the high tor who can speak eloquently employees to Sathosa, dealing or increase the prices of essen- portfolio of finance under side, the people had money to with verbosity.Though his with Prima, etc., he managed to margin more than warranted. -

The Journal of Applied Research the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka

The Journal of Applied Research The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka Vol 03, 2019 ISSN 2613-8255 Regulatory Effectiveness on Auditing and Taxation, Corporate Reporting and Contemporary Issues Investors’ Perception and Audit Expectation-Performance Gap (AEG) in the Context of Listed Firms in Sri Lanka J.S. Kumari, Roshan Ajward, D.B.P.H. Dissabandara Level and Determinants of Corporate Tax Non-Compliance: Evidence from Tax Experts in Sri Lanka Nipuni Senanayake, Isuru Manawadu The Impact of Audit Quality on the Degree of Earnings Management: An Empirical Study of Selected Sri Lankan Listed Companies Amanda Pakianathan, Roshan Ajward, Samanthi Senaratne An Assessment of Integrated Performance Reporting: Three Case Studies in Sri Lanka Chandrasiri Abeysinghe Is Sustainability Reporting a Business Strategy for Firm’s Growth? Empirical Evidence from Sri Lankan Listed Manufacturing Firms T.D.S.H. Dissanayake, A.D.M. Dissanayake, Roshan Ajward The Impact of Corporate Governance Characteristics on the Forward-Looking Disclosures in Integrated Reports of Bank, Finance and Insurance Sector Companies in Sri Lanka Asra Mahir, Roshan Herath, Samanthi Senaratne Trends in Climate Risk Disclosures in the Insurance Companies of Sri Lanka M.N.F. Nuskiya, E.M.A.S.B. Ekanayake The Level of Usage and Importance of Fraud Detection and Prevention Techniques Used in Sri Lankan Banking and Finance Institutions: Perceptions of Internal and External Auditors D.T. Jayasinghe, Roshan Ajward CA Journal of Applied Research The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka Regulatory Effectiveness on Auditing and Taxation, Corporate Reporting and Contemporary Issues CA Journal of Applied Research The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka Vol. -

Financing Catastrophic Health Expenditures in Selected Countries

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dela Cruz, Anna Mae D.; Nuevo, Christian Edward L.; Haw, Nel Jason L.; Tang, Vincent Anthony S. Working Paper Stories from Around the Globe: Financing Catastrophic Health Expenditures in Selected Countries PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2014-43 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Dela Cruz, Anna Mae D.; Nuevo, Christian Edward L.; Haw, Nel Jason L.; Tang, Vincent Anthony S. (2014) : Stories from Around the Globe: Financing Catastrophic Health Expenditures in Selected Countries, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2014-43, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127013 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Value Added Tax (Vat), Gross Domestic Production (Gdp) and Budget Deficit (Bd): a Case Study in Sri Lanka

VALUE ADDED TAX (VAT), GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCTION (GDP) AND BUDGET DEFICIT (BD): A CASE STUDY IN SRI LANKA Madhuwantha,B.G.V, Ihlas,N.M., Sampath,H.G.R., Chathuranga,P.L.S., Ruwantha,K.K.G.D, Chandrasekara,C.M.R.C, Jayalath,I.A.D, Sajath,S.M, Praboth,K.T.N, Silva,N.P.M. Abstract Almost unknown in 1960, the value-added tax (VAT) is now found in more than 130 countries, raises around 20 percent of the world’s tax revenue, and has been the centerpiece of tax reform in many developing countries including Sri Lanka.Every country needs sufficient tax revenue for their successful economic activities of their country. Imposing the tax revenue is directly link with gross domestic production and budget deficit of the country. The focus of this research paper is to find out the impact of Value Added Tax (VAT) on Budget Deficit (BD) and Gross Domestic Production (GDP) of the country and also identify the association among value added tax, gross domestic production and budget deficit in Sri Lanka. To fulfil the objective this research obtained Sri Lankan Central Bank reports (secondary data) from 2005 to 2015 and carried out a SPSS analysis. Analysis results confirmed that there is significant association between value added tax and gross domestic production and also there is significant association between value added tax and budget deficit of the country. It implies that the Sri Lankan Government should give key focus on amending and implementation of VAT because the county is facing the budget deficit continuously and here the gross domestic production impact by VAT same time VAT impact on BD of the country. -

Tax Reforms in Sri Lanka: Will a Tax on Public Servants Improve Progressivity?

working paper 2012-13 Tax reforms in Sri Lanka: will a tax on public servants improve progressivity? Nisha Arunatilake Priyanka Jayawardena Anushka Wijesinha December 2012 Tax Reforms in Sri Lanka: Will a Tax on Public Servants Improve Progressivity? Abstract The Sri Lankan government implemented tax reforms in 2011, including removal of the tax exemption given to public servants and reduction of personal income tax rates in order to improve tax compliance from pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) tax payers. This study evaluates the 2007 and 2011 tax systems in order to examine the effects that taxing the income of public sector employees has on total tax revenues and the tax base. The study also compares the distributional effects of the different tax systems. Study further conducts simulation analyses to assess the most progressive means of achieving the 2007 tax revenue levels. Implications for tax evasion are also examined under different tax systems. The study finds that the 2011 tax reforms reduce tax revenue by 48 percent relative to the structure of income taxation in 2007. This decline in tax revenues occurs even though income taxes are extended to public sector workers because the 2011 tax reforms reduced the rate of income taxes across the board and increased the tax-free threshold. Our simulations show that tax revenues would have risen if the reforms were limited to introducing income taxes to public servants. The resulting (hypothetical) tax system would also have been more progressive than the tax structure resulting from the 2011 reforms. The study evaluated the distributional impacts of modifications to the 2011 tax system which would increase tax revenue to their level in 2007. -

Staff Studies

STAFF STUDIES CENTRAL BANK OF SRI LANKA Volume 44 Nos. 1 & 2 – 2014 I ISSN 1391 – 3743 The views presented in these papers are those of the authors and do not necessarily indicate the views of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Printed at the Central Bank Printing Press, 58, Sri Jayawardenepura Mawatha, Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka. Published by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Colombo 01, Sri Lanka II CENTRAL BANK OF SRI LANKA ABOUT THE AUTHORS Ms. Erandi Liyanage is a Senior Economist attached to the Economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. She received a BA Special degree in Economics and Master of Economics degree from the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. She also obtained a Master of Economics degree from the University of Sydney, Australia. Her research interests are in the fields of financial economics, international trade, fiscal policy and macroeconomic management. Mr. Mayandy Kesavarajah is an Economist attached to the Economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. He received a BA Special Degree in Economics with First Class Honours from University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and Master of Economics from the same university. His research interests are in the fields of monetary policy, public finance and macroeconomic modelling. Mr. Chanka N Ganepola is an Assistant Director attached to the International Operations Department of Central Bank of Sri Lanka. He received a B.E. Honours degree in Computer Science and Engineering from Visvesvaraya Technological University, India. He also obtained an MBA degree in Finance from the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and and M.Sc degree in Financial Engineering from Imperial College, London. -

Indirect Taxation in Sri Lanka the Development Challenge

Indirect Taxation in Sri Lanka The Development Challenge 1 Abstract distribution. Taxation, inter alia, can Kopalapillai Amirthalingam be used as a tool to ensure such Senior Lecturer, ri Lanka is seeking rapid income distribution across Department of Economics, economic growth targeting geographical demarcations and University of Colombo. S at doubling per capita income deciles. income by 2016. Nonetheless, inequality is at its historical In the past three decades, a highest and thus the development number of developing countries the country. This situation challenge is to ensure that rapid have experienced major episodes of necessitates comprehensive policy economic growth is achieved financial crisis that were brought measures either to reduce while better ensuring equitable about by unsustainable fiscal expenditure or to increase the income distribution. Since fiscal deficits. As in the case of a number revenue base of the country, so deficit is significantly high in of other developing countries, the that the government need not Sri Lanka, taxation is crucial in fiscal deficit in Sri Lanka too has depend overwhelmingly on debt. generating government revenue been high for a long period. Though However, given the security because of the harmful the fiscal deficit was at its peak at situation and the need for rapid macroeconomic repercussions of 23 per cent of GDP in 1980, it development of the country, other means. However, tax ratio averaged 13 per cent during 1977- expenditure cuts could be harmful is on the decline and the decline 1991 and 9 per cent during 1992- not only economically, but also is closely related to the decline 2009 (Central Bank of Sri Lanka).