Impact of Kolanuts Trade on Socio-Economic Development of Sagamu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Locational Analysis of Primary Health Facilities in Ikorodu Local Government Area of Lagos State Using Multimedia GIS Approach By

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 5, May-2018 2008 ISSN 2229-5518 Locational Analysis of Primary Health Facilities in Ikorodu Local Government Area of Lagos State using Multimedia GIS Approach By Akinpelu, A.A., Ojiako, J.C., Amusa, I.A. & Akindiya, O.M. ABSTRACT Health care services deal with diagnosis and treatment of disease or the promotion, maintenance and restoration of health. The locational analysis of Primary Health Centres in Ikorodu Local Government Area of Lagos State was examined using Multimedia GIS approach. The study adopted GIS and Remote Sensing methods to look into the locations of these Primary Health care centres spread across the local government area. Geospatial database of the facilities was designed and created from where analyses were performed. Primary and secondary data types were used. The primary data are the X,Y coordinates of the Primary Health Centres while the secondary data were the administrative maps of the study area. The analyses included spatial queries, attributes queries and hyperlink that involved linking the spatial data with the pictures and audio files in the database done with ArcGIS 10.3. The spatial query showed that 5 wards have no PHC, 10 wards have 1 each, 5 wards have 2 each and 1 ward has three PHCs. The attribute query showed that 9 PHCs are located via good roads, 8 via fair roads and 6 via bad roads. Linking the picture and audio files were possible by using field-based hyperlinks and defining a dynamic hyperlink using the Identify tool. The aim and objectives of the study were achieved and recommendations were made in line with the findings. -

Surveyor General Lagos State

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICE OF THE STATE SURVEYOR GENERAL SCHEDULE OF SURVEY FEES INDEX 1. Land Information Fee. 2. Lodgment of record copy 3. Charting Information Certificate & Surveyor General’s Consent to Survey 4. Charting fee for Governor’s Consent Application 5. Ortho-photo Scale I: 2000 6. Geographical Information fees 7. Chargeable Fees for Agric Land Allocation 8. Chargeable Fees for Sub-division Survey 9. Composite Plan + Inspection Subsequently 1. LAND INFORMATION CERTIFICATE 0 2000m2 N10,000.00 2001m2 5000m2 N15,000.00 5001m2 1 Hectare N20,000.00 1 Hectare 2 Hectares N25,000.00 2 Hectares 3 Hectares N30,000.00 3 Hectares 4 Hectares N40,000.00 4 Hectares 8 Hectares N60,000.00 8 Hectares 20 Hectares N80,000.00 20 Hectares 30 Hectares N100,000.00 30 Hectares 100 Hectares N150,000.00 Above 100 Hectares N250,000.00 Note: Commercial and Industrial will pay double (X2) the fee of the above 2. LODGMENT OF RECORD COPY N1,000.50K/ Copy Note: Lodgment of a Layout Plan depends on the number of plots 3. CHARTING INFORMATION CERTIFICATE & SURVEYOR GENERAL’S CONSENT TO SURVEY FEE - Half the chargeable fee for Land Information I. CHARTING INFORMATION CERTIFICATE 0 2000m2 N5,000.00 2001m2 5000m2 N7,500.00 5001m2 1 Hectare N10,000.00 1 Hectare 2 Hectares N12,500.00 2 Hectares 3 Hectares N15,000.00 3 Hectares 4 Hectares N20,000.00 4 Hectares 8 Hectares N30,000.00 8 Hectares 20 Hectares N40,000.00 20 Hectares 30 Hectares N50,000.00 30 Hectares 100 Hectares N75,000.00 Above 100 Hectares N125,000.00 II. -

Nigeria: Badoo Cult, Including Areas of Operation and Activities; State Response to the Group; Treatment of Badoo Members Or Alleged Members (2016-December 2019)

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?... Nigeria: Badoo cult, including areas of operation and activities; state response to the group; treatment of Badoo members or alleged members (2016-December 2019) 1. Overview Nigerian media sources have reported on the following: "'Badoo Boys'" (The Sun 27 Aug. 2019); "Badoo cult" (Vanguard with NAN 2 Jan. 2018; This Day 22 Jan. 2019); "Badoo gang" (Business Day 9 July 2017); "Badoo" (Vanguard with NAN 2 Jan. 2018). A July 2017 article in the Nigerian newspaper Business Day describes Badoo as "[a] band of rapists and ritual murderers that has been wreaking havoc on residents of Ikorodu area" of Lagos state (Business Day 9 July 2017). The article adds that [t]he Badoo gang’s reign of terror has reportedly spread throughout Lasunwon, Odogunyan, Ogijo, Ibeshe Tutun, Eruwen, Olopomeji and other communities in Ikorodu. Their underlying motivation seems to be ritualistic in nature. The gang members are reported to wipe their victims’ private part[s] with a white handkerchief after each rape for onward delivery to their alleged sponsors; slain victims have also been said to have had their heads smashed with a grinding stone and their blood and brain soaked with white handkerchiefs for ritual purposes. Latest reports quoted an arrested member of the gang to have told the police that each blood-soaked handkerchief is sold for N500,000 [Nigerian Naira, NGN] [approximately C$2,000]. (Business Day 9 July 2017) A 2 January 2018 report in the Nigerian newspaper Vanguard provided the following context: It all started after a suspect, described by some residents of Ikorodu area as a "serial rapist and ritual killer," was arrested at Ibeshe. -

Appropriation Bill 2021

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT ANNEXURE II MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING AND BUDGET Y2021 BUDGET PROPOSAL Y2021 OMNIBUS TABLE REVENUE(CRF) N General Public Services 705,128,514,363 Governance 2,046,600,000 1 026 Deputy Governor's Office 1,000,000 2 002 Secretary to the State Government 1,000,000 Office/ Cabinet Office 3 032 Office of Civic Engagement 4 Office of the Chief of Staff 2,200,000 5 070 Project Implementation and Monitoring Unit 6 Central Internal Audit Department 7 029 Parastatal Monitoring Office 3,000,000 8 Office of Public Private Partnership 2,000,000,000 9 075 PPP (Outstanding) 10 PPP slip Roads, Bridges and Pedest. Bridges 11 022 Liaison Office 35,000,000 12 027 Office of the Auditor General for 1,500,000 Local Government 13 028 Office of the State Auditor General. 2,600,000 14 073 Audit Service Commission(ASC) 300,000 1 17/12/20203:13 PM LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT ANNEXURE II MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING AND BUDGET Y2021 BUDGET PROPOSAL Y2021 OMNIBUS TABLE REVENUE(CRF) N 073 15 ASC(RENT) 16 051 Office of Transformation, Creativity - and Innovation House of Assembly 70,000,000 17 019 House of Assembly 70,000,000 18 072 House of Assembly Commission Economic Planning and Budget 1,500,000 19 020 Ministry of Economic Planning & 1,500,000 Budget(HQ) 20 Statistical Survey and Research 21 Consultancy 22 Local Governments Performance Challenge 23 Global Citizens'/ Conferences 24 Resilience Office 25 Socio- Economic Branding and Communication 26 MEPB GOC(Statewide) 27 Current Outstanding Liabilities 2 17/12/20203:13 PM 020 LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT -

Lagos State Agricultural Development Authority Oko-Oba, Agege

LAGOS STATE AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY OKO-OBA, AGEGE EXTENSION ACTIVITIES REPORT (JANUARY-DECEMBER 2016) PRESENTED AT THE REFILS WORKSHOP ON OFAR/EXTENSION REPORT HELD BETWEEN 25TH- 28TH , APRIL 2017 AT THE IAR&T TRAINING ROOM, MOOR PLANTATION IBADAN. INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND The Farmer’s needs and problems were highlighted statewide during the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) that was conducted on a zonal basis in November, 2015. Farmers’ Representatives, Subject Matter Specialists, Extension Agents and their Supervisors, Input Dealers, PM& E Officers and representatives of Agricultural institutions in each block participated in the Rural Appraisal. Thus, the Extension Programme for the year 2016 was centered on the Community- Based Participatory Group Approach towards extension services delivery. The Calendar of MTRM and FNT topics for the year was selected based on the PRA report and were subsequently approved. The component continued the dissemination of technical messages on the popularization of new cassava varieties for better yield i.e. TMS98/0518, Use of dietary garlic powder (allium sativum) inclusion in the diets of clarias gariepinus, processing method of fresh ginger paste on the shelf-life of smoked fish e.t.c . This year, the component introduced various new technologies to farmers in the state such as Popularization on the use of rice offal inclusion in the diets of growing pigs, use of supplementary rations for growth performance in goats. E.t.c. Extension activities during the year 2016 picked up through the various needs of farmers, their receptiveness as well as resources that were made available to the Component. This ensured qualitative adoption of these messages at a sustainable level. -

INTRODUCTION Lagos State with Population of Over 10 Million

Ife Journal of Science vol. 14, no. 1 (2012) 75 INTEGRATED GEOPHYSICAL AND GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF A BRIDGE SITE - A CASE STUDY OF A SWAMP/CREEK ENVIRONMENT IN SOUTH EAST LAGOS, NIGERIA Salami, B. M.*, Falebita, D. E.*, Fatoba, J.O**, and Ajala, M.O*** * Department of Geology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria ** Department of Earth Science, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago- Iwoye, Nigeria *** Row-Dot Ltd, Lagos Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Received: 4th Nov., 2011; Accepted: 23rd May, 2012) ABSTRACT Integrated geophysical and geotechnical investigation was carried out at a bridge site within a creek and swamp environment in parts of Agbowa, South East Lagos. This was with a view to delineating the subsoil sequence and determining the engineering properties. The investigation involved three shell and auger boring and seven Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) using the Schlumberger electrode array. Analysis of results of the boring lithological logs indicates occurrence of four major layers composed of clay, organic clay, silty sandy clay and sandy deposits to about 40 m depth. Results of the in-situ and laboratory tests reveal that the silty-sandy soils are characterized by low N-values that range from 5 to 15, while the clayey soils are characterized by high void ratio of 1.73 and low Cu values of 22 kN/m20 with 4 indicating the poor strength and highly compressible nature of the subsoil sequence. The electrical resistivity survey results show good correlation with boring logs and further indicated occurrence of a highly resistive (>1000 ohm-m) basal sandy deposit beyond the boring probe to appreciable depth of over 80 m. -

Economic Development in Urban Nigeria

RESEARCH REPORT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN URBAN NIGERIA JULY 2015 ROBIN BLOCH NAJI MAKAREM ICF International Univeristy College London MOHAMMED-BELLO YUNUSA NIKOLAOS PAPACHRISTODOULOU Ahmadu Bello University ICF International MATTHEW CRIGHTON ICF International i Rights and Permissions Except expressly otherwise noted or attributed to a third party, this report is © 2014 ICF International, under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial- ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA. Please cite as follows: Bloch R., Makarem N., Yunusa M., Papachristodoulou N., and Crighton, M. (2015) Economic Development in Urban Nigeria. Urbanisation Research Nigeria (URN) Research Report. London: ICF International. Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA. Comments or enquiries related to this report or its datasets, which are available on request, should be addressed to [email protected] Cover photo: Nikolaos Papachristodoulou. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................... ii ACRONYMS .......................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 4 NIGERIA’S ECONOMY TODAY ................................................................. 6 KEY MACROECONOMIC TRENDS ................................................................... 6 NATIONAL INDUSTRIAL COMPOSITION -

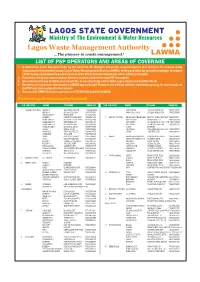

List of Psp Operators and Areas of Coverage 1

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT Ministry of The Environment & Water Resources Lagos Waste Management Authority ...The pioneer in waste management! LAWMA LIST OF PSP OPERATORS AND AREAS OF COVERAGE 1. In furtherance of the Executive Order by the Governor, Mr. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, on government's zero tolerance for reckless waste disposal and environmental abuse, Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA), hereby publishes for general knowledge, the names of PSP operators mandated to provide services in the 20 Local Government Areas and 37 LCDAs in the state. 2. Remember to bag your wastes and put them in covered containers for easy PSP evacuation. 3. Also endeavour to pay promptly your waste bills, as we collectively work to make Lagos cleaner and healthier for all. 4. Residents are enjoined to download the LAWMA app on Google Playstore and visit our website, www.lawma.gov.ng, for more details on the PSP operators assigned to their streets. 5. You can call LAWMA for back up services on 07080601020 and 08034242660. #ForAGreaterLagos #KeepLagosClean #PayYourWastebill S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO 1 AGBADO OKE ODO ABORU I GOFERMC NIG LTD "08038498764 OMITUNTUN IYALAJE WASTE CO. "08073171697 ABORU II MOJAK GOLD ENT "08037163824 SANTOS/ILUPEJU GOLDEN RISEN SUN "08052323909 ABULE EGBA II FUMAB ENT "08164147462 AGBADO CHRISTOCLEAR VENT "08058461400 7 AMUWO ODOFIN ABULE ADO/TRADE FAIR NEXT TO GODLINESS ENT "08033079011 AGBELEKALE I ULTIMATE STEVE VENT "08185827493 ADO FESTAC DOMOK NIG LTD "08053939988 AGBELEKALE II KHARZIBAB ENT "08037056184 EKO AKETE OLUWASEUN INV. COY LTD "08037139327 AGBELEKALE III METROPOLITAN "08153000880 IFELODUN GLORIOUS RISE ENT "08055263195 AGBULE EGBA I WOTLEE & SONS "08087718998 ILADO RIVERINE AJASA BOIISE TRUST "08023306676 IREPODUN CARLYDINE INV. -

Y2018 Budget Omnibus and Summary Position

LAGOS STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Y2018 APROVED BUDGET SUMMARY POSITION Y2018 FISCAL ITEMS Approved Budget ₦m A TOTAL REVENUE 897,423 B TOTAL INTERNALLY GENERATED REVENUE (C+D) 720,123 C INTERNALLY GENERATED REVENUE 680,583 i Lagos Internal Revenue Services 440,121 ii Internally Generated Revenue(Other) 209,357 iii Dedicated Revenue 26,105 iv Investment Income 3,000 v Extra Ordinary Revenue 2,000 D CAPITAL RECEIPTS 39,540 i Grants 19,525 ii Other Capital Receipts 20,015 E Federal Transfers 177,300 i Statutory Allocation 57,500 ii Value Added Tax 103,200 iii Extra Ordinary Revenue 15,100 iv 13% Derivations 1,500 F RECURRENT EXPENDITURE (DEBT AND NON-DEBT) 347,039 G RECURRENT DEBT 35,906 i Debt Charges( External) 5,813 ii Debt Charges (Internal) 23,093 iii Debt Charges (Bond) 7,000 H RECURRENT NON DEBT 311,133 I Total Personnel Costs 112,242 i Personnel Costs (Basic and Allowance) 79,012 ii Personnel Costs (Consolidated) 2,064 iii NYSC /Interns (Allowances) 300 iv Other Personnel Cost (Contingency) 3,206 v 7.5% Govt. Share to Pension Contribution 3,800 vii 2.5% Govt. Share to Pension Contribution - viii 5% BSA (Pension Redemption Bond Fund) 7,733 ix Pension Redemption Bond Fund Shortfall 6,150 x Pension & Gratuities (Civil Service/ Teaching Services) 3,519 xi 142% Pension & Gratuities (Civil Service/ Teaching Services) 1,074 xii 6% Pension & Gratuities (Civil Service/ Teaching Services) 82 xiii 15% Pension & Gratuities (Civil Service/ Teaching Services) 375 xiv Pension & Gratuities (Judiciary) 522 xv Retirement Planning/Contingencies Expenses/Pensions 300 xvi Pension Sinking Fund 2,400 xvii Severance Pay (Pol. -

LGA LCDA List of Roads Length Pavement Agege 1A JJ Oba Remo Road,Agege Ajakaye/Arigidi/Elicana 718 Asphaltic Concrete

LGA LCDA List of Roads Length Pavement Agege 1a JJ Oba Remo road,Agege Ajakaye/Arigidi/Elicana 718 Asphaltic Concrete Awori/Adesokan 820 Asphaltic Concrete Orile Agege Igbayilola/Kusoro/Olabode Olaiya Road 864 Asphaltic Concrete ILogbe street 562 Interlocking pavement stone Ajeromi - Ifelodun Ajeromi Uzor street 790 Interlocking pavement stone Akogun road 680 Interlocking pavement stone Ifelodun Adekoya/Owoyemi street 930 Interlocking pavement stone Adejiyan street 565 Interlocking pavement stone Alimosho Alimosho Jimoh Akinremi/Ogunbiyi street 947 Asphaltic Concrete Olarewaju/Soyombo Alaka street 563 Asphaltic Concrete Olawale cole 395 Asphaltic Concrete Oki Road 650 Asphaltic Concrete Ayobo Ipaja Baba Kaka street 935 Asphaltic Concrete Yusuf street 603 Asphaltic Concrete Egbe Idimu Community road,Agodo 822 Asphaltic Concrete Oduwole street 810 Asphaltic Concrete Igando Ikotun Tanimowo/Oladepo/Abibatu 762 Asphaltic Concrete Rufia Ashimi/Abuba Anthony street 746 Asphaltic Concrete Mosan Okunola Awori street Akinogun 302 Asphaltic Concrete 1st Avenue Abesan Estate 513 Asphaltic Concrete Amowo-Odofin Amowo odofin Agidimo Road Jakande Estate 360 Interlocking pavement stone 512 Road Festac Town 700 Interlocking pavement stone Oriade Omila Street,Onireke Barrack 955 Interlocking pavement stone Ade Oshodi Street 685 Interlocking pavement stone Apapa Apapa Itapeju/mushin Road 400 Asphaltic Concrete Payne Crescent/Oniru 680 Asphaltic Concrete Iganmu Akosile street off Gaskiya 364 Asphaltic Concrete Sadiku/Oluwatoyin/Ajagbe/adunni 850 Asphaltic -

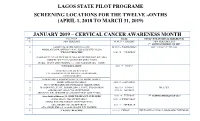

Lagos State Pilot Programe Screening Locations for the Twelve Months

LAGOS STATE PILOT PROGRAME SCREENING LOCATIONS FOR THE TWELVE MONTHS (APRIL 1, 2018 TO MARCH 31, 2019) JANUARY 2019 – CERVICAL CANCER AWARENESS MONTH S/N LOCATION DATE NOTES (FOR INTERNAL REFERENCE) 1. NEW YEAR DAY 01.01.19 – TUESDAY NEW YEAR DAY 2019 1ST #GIVINGTUESDAY OF 2019 2. LAGOS STATE FIRE SERVICE (LSFS) 02.01.19 – WEDNESSDAY B/D: “F.I.R.E” (1ST OF JAN) MOBOLAJI BANK ANTHONY WAY, IKEJA BUS STOP, IKEJA 3. *TWO OUTREACHES* 03.01.19 – THURSDAY IFAKO-IJAIYE LGA SECRETARIAT: NO 1 OLUWATOYIN ST, OFF AINA AJOBO ST, OFF YAYA ABATAN RD, OGBA- IJAIYE IFAKO – IJAIYE MINI STADIUM, 1/2, COLLEGE RD IFAKO – IJAIYE 4. *TWO LOCATIONS* 04.01.19 – FRIDAY OJOKORO LCDA SECRETARIAT 9/11, AGBADO STATION RD (IJAIYE OJOKORO RD), IJAIYE-OJOKORO ASIWAJU BOLA AHMED TINUBU ULTRA MODEL MARKET 5. OJODU LCDA SECRETARIAT: 05.01.19 – SATURDAY NO 1-3 SECRETARIAT RD, POWERLINE, OKEIRA, OGBA 6. IBA HOUSING ESTATE, BEHIND ZONE E FENCE, OTO-IJANIKIN 06.01.19 – SUNDAY THE EPIPH. 7. AGBADO/OKE-ODO LCDA SECRETARIAT: 07.01.19 – MONDAY ABEOKUTA E/W, OPPOSITE OJA-OBA BUS STOP, ABULE EGBA 8. mass medical mission | 31, BODE THOMAS ST, SURULERE 08.01.19 – TUESDAY 2ND #GIVINGTUESDAY OF 2019 9. AYOBO-IPAJA LCDA SECRETARIAT: 09.01.19-WEDNESDAY AYOBO-IPAJA RD, IGBOGILA BUS STOP, IPAJA 10. OTO-AWORI LCDA SECRETARIAT: 10.01.19 – THURSDAY OTO-AWORI, KM 28, LAGOS-BADAGRY E/W, IJANIKIN 11. *TWO OUTREACHES* 11.01.19 – FRIDAY THE TONYE COLE DAY (DIAMOND CENTURION) MAKOKO COMMUNITY INT’L THANK YOU DAY YABA LCDA SECRETARIAT: 198 H/MACAULAY ST, ADEKUNLE, YABA 12. -

Spatial Technology in Evaluating Accessibility Birth / Death Registration Centers in Ikorodu Local Government Area

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 31 (2016) 47-70 EISSN 2392-2192 Spatial Technology in Evaluating Accessibility Birth / Death Registration Centers in Ikorodu Local Government Area S. O. A. Oloyede-Kosoko1,a, Idowu Adigun Amusa1,b, Oluwafemi Idowu Adetimirin1,c, Aigbedion Imuwahen Priscilla1, Adeola Esther Foluke2 1Department of Geoinformatics, Federal School of Surveying, P.M.B. 1024 Oyo, Nigeria 2National Population Commission, Ikorodu Local Government Area, Lagos State, Nigeria a-cE-mail address: [email protected] ; [email protected] ; [email protected] ABSTRACT Evaluating the accessibility of NPC birth and death registration centers in Ikorodu LGA of Lagos state was conceived to manage the citing of birth and death registration centers. Digital database that is consistent and devoid of redundancy that enables data sharing at the end. National Population Commission will be a note among the geo-spatial data information infrastructures in the National geospatial frame. Therefore, the design of a geo-demographic digital database has seriously become more useful and eminent for National Population Commission to establish a programmatic database that will allow for easy update and retrieval. This structure is expected to provide for the implementation of a proper GIS in the National Population Commission nationwide. Keywords: Accessibility; Digital Database; Geo-Demographic; Geographic Information System World Scientific News 31 (2016) 47-70 BACKGROUND INFORMATION Population census is the greatest relevance to the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural planning of any country. Population census can be defined as the total process of collecting, compiling and publishing demographical data in a defined territory (FGN, 2004). Census data are required for planning and administration and for many aspects of economic and social research and also provides reliable and detailed statistical data on the demographic, social, national, housing, sub national and local levels, thus meeting information needs.