Finding Lewis-Like Joy in the Music of Sergei Rachmaninoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rach-Three Rocks Meadowbrook

d RACHTHREE ROCKS MEADOWBROOK: A Retrospective Review By Chris Brockman If aesthetic experiences ever come up in a conversation (and they do occasionally), I am ready to recount my greatest one of all. It happened at the Meadowbrook Music Festival, Au gust 30, 1969, and it was hearing and seeing Andre Watts play Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the Detroit Sym phony, conducted by Seiji Ozawa. There are clear reasons why this performance remains embedded in my conscious ness after forty years. I’d like to present these in sharing one of the best things that happened to me as a student at Oak land University Back in those days and at least until I graduated in 1971, O.U. students could attend Meadowbrook concerts for free, if they sat on the hill. This was a wonderful advantage for me and, I’m sure, for other students. For one thing, I had married in the middle of the ’67–68 school year, and by the time of the 1969 concert my wife and I had a baby to take care of. We lived in the Coral Ridge Apartments in Rochester, and to make our $135 a month rent, my wife worked at the Brass Lamp in Rochester. I delivered pizzas for Little Caesar in Pontiac and worked for my father, a paint contractor, in the summer. (At various times, I did painting at Sunset Manor, Meadowbrook Hall, the Meadowbrook greenhouse, the old stables, and even 92 the children’s playhouse. I also helped paint the dressing rooms under the stage at the Baldwin Pavilion!) The gist of all this is that my wife (also an O.U. -

Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice Tanya Gabrielian The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2762 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACHMANINOFF AND THE FLEXIBILITY OF THE SCORE: ISSUES REGARDING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE by TANYA GABRIELIAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 Ó 2018 TANYA GABRIELIAN All Rights Reserved ii Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Anne Swartz Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Geoffrey Burleson Sylvia Kahan Ursula Oppens THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian Advisor: Geoffrey Burleson Sergei Rachmaninoff’s piano music is a staple of piano literature, but academia has been slower to embrace his works. Because he continued to compose firmly in the Romantic tradition at a time when Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg variously represented the vanguard of composition, Rachmaninoff’s popularity has consequently not been as robust in the musicological community. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

716 759-2600 • • P 2013 50236-MCD Liner Notes by Wanda Brister and Scott Pool Trio Vocalise

Scott Pool Since 2009, Scott Pool has served as Assistant Professor of Bassoon at the University of Texas Arlington. He has also been a faculty member/performer with the Orfeo International Music Festival (Italy), the Schlern International Music Festival (Italy), and from 2002-09 was Associate Professor of Bassoon at Valdosta State University (GA). Recognized as a Moosmann Artist, Scott has performed concerts and recitals throughout North and South America and Europe, and his bassoon performances have been featured on National Public Radio and from local to national television broadcasts. An avid proponent of new music, Scott has played an active role in either direct commissions or consortiums from both established and emerging contemporary composers, including Katherine Hoover, Chris Arrell and Jenni Brandon. In addition to Vocalise, Scott can also be heard on Landscapes: The Double Reed Music of Daniel Baldwin (2010), also released on Mark Records. Scott has served as principal bassoon with the Valdosta Symphony Orchestra and the Albany (GA) Symphony Orchestra, the Savannah Symphony Orchestra and has performed with the Plano Symphony Orchestra (TX), the Tucson Pops, the Tucson Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestra Symphonica UANL of Monterry, Mexico and the Oklahoma City Philharmonic. Technical Details: Recording Engineer: Micah Hayes Assistant Engineer: Eric Morrison, Micah Breedlove, Mark Gutiérrez, and Kory Morris Sound Technicians: Wanda Brister, Michael Evans, Amber Wyman and Lorraine Dow Editing and mastering: Fred Betschen Art design and layout: Jason Boldt, MarkArt Mark Records • 10815 Bodine Road • Clarence, NY 14031-0406 Ph: 716 759-2600 • www.markcustom.com • P 2013 50236-MCD Liner notes by Wanda Brister and Scott Pool Trio Vocalise Vocalise – Vocalise by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) is one of his best-known melodies. -

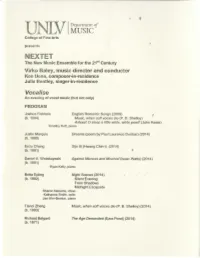

Vocalise an Evening of Vocal Music (B Ut Not Only)

Department of MUSIC College of Fine Arts presents E The New Music Ensemble for the 21 st Century Virko Ba ley, music director and conductor Ken Ueno, composer-in-residence Julia Bentley, singer-in -residence Vocalise An evening of vocal music (b ut not only) PROGRAM Joshua Fishbein English Romantic Songs (2009) J (b.1984) Music, when soft voices die (P. B. Shelley) Asleep! 0 sleep a little while, white pearl! (John Keats) Timothy Haft, piano Justin Marquis Dreams (poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar) (2014) (b. 1989) Enzu Chang Sijo Ill (Hwang Chin-i) (2014) (b . 1981) Daniel A. Watabayashi Against Idleness and Mischief (Issac Watts) (2014) (b. 1991) Ryan Kelly, piano Britta Epling Night Scenes (2014) (b. 1992) Silent Evening From Shadows Midnight Escapade Sharon Nakama, oboe Katharine Smith, cello Jae Ahn-Benton, piano Tianci Zheng Music, when soft voices die (P. B. Shelley) (2014) (b. 1993) Richard Belgard The Age Demanded (Ezra Pond) (2014) (b. 1971) Maxwell R. Lafontant Memories Lost (Tyler Hag y) (2011, rev. 2014) (b. 1990) Jae Ahn-Benton, piano INTERMISSIO N Virko Baley From the Emily Dickinson Songbook (2000) (b . 1938) Love Can Do Al l But Rraise the Dead Oh, Honey of an Hour There is a Solitude of Space Timothy Haft, piano Jennifer Bellar Songs of Ethereality (revised 2014) (b . 1983) 1. Air and Angels (John Donne) 2. The Distant (Yannis Ritsos) 3. Perhaps Not to Be (Pablo Neruda) Timothy Haft, piano Ken Ueno WATT - for baritone saxophone, percussion, (b. 1971) and electronic sounds (2000) Justi n Marquis, baritone sax Caleb Pickering, pe rcussion Ken Ueno I pulse, when you breathe (Ken Ueno) (2008) Carmella Cao, alto fl ute Ken Ueno The Aleph Ken Ueno, singer Monday, December 1, 2014 7:30 p.m. -

Sección General

Sección General Vocalize genre in the Sergey Rachmaninoff’s works Vocalizar el género en las obras de Sergey Rachmaninoff K rasov V. V.* State Music Pedagogical Institute named after M.M. Ippolitov-Ivanov - Russia [email protected] ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to determine the semantics of vocalize in the S. Rachmaninoff’s works. An integrated approach, combining general aesthetic, source studying, historical and stylistic and systemic genre ones, allowed considering such a capacious concept as vocalise. On the basis of the method of complex analysis the results about the uniqueness of vocalize as an artistic definition are obtained. Vocalize has gone a long historical path of development from the original form (as a technical exercise to develop the voice) to its concert kind of solo vocalise, which appeared in the S. Rachmaninoff’s work. Not limited to an independent genre, vocalize penetrates into chamber vocal music. Based on the analysis of these works, the conclusion is made about the uniqueness and universality of the expressive properties of choral vocalise. Special attention is paid to choral vocalize as a means of choral texture. Based on the analysis of the works “Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom”, “Nightlong vigil”, choral scenes of the opera “Francesca da Rimini”, cantata “Spring”, poem “Bells”, “Three Russian songs” the conclusion about the manifestation of instrumentality in the choral texture is made. In general, the analysis of Rachmaninoff’s musical heritage allows affirming vocalize in the status of the artistic universe. Keywords: S. Rachmaninoff, vocalise, semantics, genre, style, drama. RESUMEN El propósito del estudio es determinar la semántica de la vocalización en las obras de S. -

ARSC Journal, Spring 1993 71 Sound Recording Reviews · Leading a Major American Orchestra, Deciding Instead to Concentrate on a New Career As a Concert Pianist

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Sergei Rachmaninoff-The Complete Recordings. Sergei Rachmaninoff, pianist and conductor, with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy, conductors. Recorded 1919-1942. RCA Victor Gold Seal 61265-2 (10 CDs, ADD). Forty years after his death, Sergei Rachmaninoff remains one of the most significant musicians of the twentieth century. As a composer, Rachmaninoff has been maligned severely over the years, indeed, even during his own lifetime, as an outmoded holdover from a bygone romantic tradition. Yet being outmoded is not sufficient justification for dismissing a composer's work, and Rachmaninoff certainly was not the first composer to be considered dated in his own lifetime. It is worth remembering that J. S. Bach also was considered "old-fashioned" near the end of his life. Rachmaninoff was certainly Bach's equal as a composer (he has much company) but he easily ranks with a large number of second-string, not second-rate, composers whose works occupy a significant place in the repertoire, including Respighi, Holst, and Scriabin. Rachmaninoff's Preludes and Etudes-Tableux are hardly a re-hashing of the solo piano writing of Chopin, Schumann, and Liszt. They are strikingly original works whose musical challenges are as significant as the more obvious technical demands. Of all the romantic pianist-composers, Rachmaninoff produced the most extensive output of music for piano and orchestra. Unlike Chopin, whose orchestral writing in his Concerti is quite inept, Rachmaninoff was a highly skillful orchestrator. This is not only evident in his Second Symphony, The Isle ofthe Dead, and The Bells, but also in his operas, which remain virtually unknown in the western hemisphere. -

Vocalise Rachmaninoff and Poulenc

Vocalise Rachmaninoff and Poulenc 2:30PM | Sunday | 21 October 2018 Sydney Opera House Press Play. PLAYING FROM ALBUM Prokofiev: Visions fugitives Visions Fugitives, Op. 22: VIII. Com... Maria Raspopova, Omega Ensemble 0:40 -1:07 The music continues on Spotify, iTunes and Google Play. Stay tuned in 2019 as we release more live performances and studio recordings on Omega Classics. Vocalise Rachmaninoff and Poulenc Sunday 21 October 2018 Francis Poulenc 2:30pm Chanson d’Orkenise (Banalités) Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House Hôtel (Banalités) Voyage à Paris (Banalités) Presented as part of the 2018 Master Series C (Deux Poèmes de Louis Aragon) Air Vif (Air Chantes) Violon (Trois Poemès de Louise de Vilmorin) Les Gars qui vont a la fête (Chanson Villageoises) Sergei Rachmaninoff Selections from 14 Romances, Op.34 Vocalise Muza Arion Voskresheniye Lazarya Kakoye Schast’ye Ian Munro Letter to a Friend (Words by Judith Wright) [Australian premiere] Franz Schubert The Shepherd on the Rock The concert will last approximately 75 minutes without interval Please ensure your mobile devices are turned to silent and switched off for the full duration of this performance. Please note that unauthorised recording or photography of this performance is not permitted. Omega Ensemble reserves the right to alter scheduled artists and programs as necessary. About the music Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Apollinaire’s love of Paris and consequent contempt for Selected Chansons, Banalités and anywhere else. Poemes One of two poems by Louis Aragon that Poulenc set in 1943, ‘C’, as Bernac once wrote, “evokes the tragic days I. Chanson d’Orkenise (Banalités S 107) on May 1940, when a large part of the French population II. -

Solo Repertoire

Solo Repertoire Bach, J.C. Cello Concerto in c minor Bach, J.S. Arioso Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major Cello Suite No. 2 in d minor Cello Suite No. 3 in C Major Cello Suite No. 5 in c minor Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major Chaconne in d minor, trans. for cello, from Partita no. 2 for solo violin Barber Cello Concerto in a minor, op. 22 Bartok First Rhapsody, transcribed for cello and piano Beethoven Cello Sonata in g minor, op. 5, no. 2 Cello Sonata in A Major, op. 69, no. 3 Bibik Cello Concerto no. 2, op. 144† Bloch Prayer Schelomo, for cello and grand orchestra Breval Cello Concerto No.2 in D Major Boccherini Cello Concerto in B-flat Major Bottermund-Starker Variations on a Theme by Paganini, for solo cello Brahms Double Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 Cello Sonata in e minor, op. 38 Cello Sonata in F Major, op. 99 Britten Suite No. 1 for solo cello, op. 72 Suite No. 2 for solo cello, op. 80 Suite No. 3, for solo cello, op. 87 Symphony for Cello and Orchestra, op. 68 Bruch Kol Nidre, op. 47 Cassado Requiebros, for cello and piano Suite for solo cello Chopin Polonaise Brillante for cello and piano, op. 3 Cello Sonata in g minor, op. 65 Casals Song of the Birds Corelli Grave Davidoff At the Fountain in D Major, op. 20, no. 2 Debussy La fille aux cheveux de lin, transc. Cello and piano Cello Sonata in D Minor Dutilleux Trois Strophes sur le nom de Sacher Dvořák Cello Concerto in b minor, op. -

Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14 Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 18

Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14 Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 18 Featuring Sean Botkin, Piano Conducted by Henry Duitman, founding Conductor of NISO Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 Christopher Stanichar, HENRY DUITMAN, SEAN BOTKIN, Principal Conductor CONDUCTOR piano WELCOME Good evening, ROGRAMPROGRAM Welcome to the Spring Concert “Rocky! An P __________________ All-Rachmaninoff Program.” I am pleased that THE NORTHWEST IOWA SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Henry Duitman, founding NISO conductor, Christopher Stanichar, Principal Conductor is back to conduct a piano concerto featuring Henry Duitman, Guest Conductor Sean Botkin, Piano Sean Botkin. I know that you will enjoy the concert this evening! This is the grand finale of the 30th 11 April 2017 anniversary season. We say a big thank you to people who played in the symphony, people who served on the NISO board, and people who were part of the Friends organization over the past 30 years. Your contributions have made NISO successful! RACHMANINOFF Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14 Before intermission our principal conductor Christopher Stanichar will introduce our 2017- 2018 season “Symphonic Treasures.” We have RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. 2, in C Minor, Op. 18 an excellent roster of concerts for next year. I. Moderato This evening there is opportunity to purchase season tickets at a reduced price.WELCOME________________________ Also remember II. Adagio sostenuto – Più animato to buy coffee, truffles, Dearand NISO 30th friends, anniversary III. Allegro scherzando Celebrating 30 years: Welcome to the opening concert of our 30th Anniversary season, "Musical CDs to continue your supportGems of." Tonight NISO. we Wehear aremusic telling stories and creating visual images, music considered looking forward to anothersome fantastic of the most well season-known and well-liked program music. -

Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Born at Oneg, Novgorod Region. He had piano lessons from an early age but his serious training in composition began at the Moscow Conservatory where he studied counterpoint with Sergei Taneyev and harmony with Anton Arensky. He began to compose and for the rest of his life divided his musical time between composing, conducting and piano playing gaining great fame in all three. After leaving Russia permanently in 1917, the need to make a living made his rôle as a piano virtuoso predominant. His 4 Piano Concertos, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and substantial solo piano works make him one of the world's most-performed composers. However, he also composed operas, liturgical choral works as well as other pieces for orchestra, chamber groups and chorus. Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op.13 (1895) Alexander Anissimov/National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland ( + Capriccio on Gypsy Themes) NAXOS 8.550806 (1999) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Philharmonia Orchestra SIGNUM SIGCD484 (2017) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2 and 3, The Bells, Symphonic Dances and The Isle of the Dead) DECCA 455798-2 (3 CDs) (1998) (original LP release: DECCA SXDL 7603/LONDON LDR 71103) (1982) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Sydney Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2 and 3, Youth Symphony, Symphonic Dances, The Isle of the Dead, Capriccio on Gypsy Themes, Aleko: Suite, The Rock, Scherzo in D minor, Prince Rostislav, Vocalise and Rachmaninov/ Respighi: 5 Etudes Tableaux) EXTON EXCL 00018 (5 CDs) (2008) Heinz Bongarz/Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra URANIA C-7131 (LP) Charles Dutoit/Philadelphia Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

RR-147 Rachmaninoff Works for Piano Trio

RACHMANINOFF P I A N O T R I O A P R O F . J O H N S O N R E C O R D I N G Alexander Siloti, in association with the Azovo‐Donskyi �� Bank, to help indigent musicians), the Rachmaninoff family was able to pay for and find passage from Oslo, Wor o io io Norway to New York on November 1st, 1918. It should be noted that Baron Nikolai Gustavovich von Struve fter the social unrest and (1876‐1920), a student of Felix Draeseke’s in Dresden, political turmoil of the 1905 was the dedicatee of Rachmaninoff’s tone poem, Isle of Russian Revolution, Rachman‐ the Dead, Op. 29 (“Herrn Nicolas von Struve inoff left Moscow with his freundschaftlich gewidmet”). Baron Nikolai von Struve Afamily for Dresden, Germany in November was a member of Tsar Nikolas II’s personal entourage, A. SILOTI 1906. This vibrant city, full of art, culture, and a prominent figure in the social and musical life of and music, became the Rachmaninoff’s the Russian capital before the Revolution. He was connected with the home for the next three years, with only Russicher Musikverlag in Petrograd (a publishing enterprise devoted to the short summer breaks at Ivanovka (the best interests of modern Russian composition) until its confiscation by the estate of his wife’s family, the Satins, near Soviet authorities. He was also a member, and later director, of the editorial Tombov). While in Dresden, Rachmaninoff board of Serge Koussevitzky’s Editions Russes de Musique. By the end of agreed to perform and conduct in the 1915, Rachmaninoff also had finished his 14 Romances (Op.