"Incident in the Gulf" Supplementary Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Army Leadership

8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 2 Leadership Track Section 1 INTRODUCTION TO ARMY LEADERSHIP Key Points 1 What Is Leadership? 2 The Be, Know, Do Leadership Philosophy 3 Levels of Army Leadership 4 Leadership Versus Management 5 The Cadet Command Leadership Development Program e All my life, both as a soldier and as an educator, I have been engaged in a search for a mysterious intangible. All nations seek it constantly because it is the key to greatness — sometimes to survival. That intangible is the electric and elusive quality known as leadership. GEN Mark Clark 8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 3 Introduction to Army Leadership ■ 3 Introduction As a junior officer in the US Army, you must develop and exhibit character—a combination of values and attributes that enables you to see what to do, decide to do it, and influence others to follow. You must be competent in the knowledge and skills required to do your job effectively. And you must take the proper action to accomplish your mission based on what your character tells you is ethically right and appropriate. This philosophy of Be, Know, Do forms the foundation of all that will follow in your career as an officer and leader. The Be, Know, Do philosophy applies to all Soldiers, no matter what Army branch, rank, background, or gender. SGT Leigh Ann Hester, a National Guard military police officer, proved this in Iraq and became the first female Soldier to win the Silver Star since World War II. Silver Star Leadership SGT Leigh Ann Hester of the 617th Military Police Company, a National Guard unit out of Richmond, Ky., received the Silver Star, along with two other members of her unit, for their actions during an enemy ambush on their convoy. -

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES the Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES The Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard Major General Raymond F. Rees assumed duties as The Adjutant General for Oregon on July 1, 2005. He is responsible for providing the State of Oregon and the United States with a ready force of citizen soldiers and airmen, equipped and trained to respond to any contingency, natural or manmade. He directs, manages, and supervises the administration, discipline, organization, training and mobilization of the Oregon National Guard, the Oregon State Defense Force, the Joint Force Headquarters and the Office of Oregon Emergency Management. He is also assigned as the Governor’s Homeland Security Advisor. He develops and coordinates all policies, plans and programs of the Oregon National Guard in concert with the Governor and legislature of the State. He began his military career in the United States Army as a West Point cadet in July 1962. Prior to his current assignment, Major General Rees had numerous active duty and Army National Guard assignments to include: service in the Republic of Vietnam as a cavalry troop commander; commander of the 116th Armored Calvary Regiment; nearly nine years as the Adjutant General of Oregon; Director of the Army National Guard, National Guard Bureau; over five years service as Vice Chief, National Guard Bureau; 14 months as Acting Chief, National Guard Bureau; Chief of Staff (dual-hatted), Headquarters North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). NORAD is a binational, Canada and United States command. EDUCATION: US Military Academy, West Point, New York, BS University of Oregon, JD (Law) Command and General Staff College (Honor Graduate) Command and General Staff College, Pre-Command Course Harvard University Executive Program in National and International Security Senior Reserve Component Officer Course, United States Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 1 ASSIGNMENTS: 1. -

The Fallen Spc

The Fallen Spc. Paul Anthony Beyer — 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), U.S. Army Sgt. Michael Edward Bitz — 2nd Assault Amphibious Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, Task Force Tarawa, 2nd Marine Division, U.S. Marine Corps Spc. Philip Dorman Brown — B Company, 141st Engineer Combat Battalion, N.D. Army National Guard Spc. Keenan Alexander Cooper — A Troop, 4th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division, U.S. Army Spc. Dennis J. Ferderer, Jr. — Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade, Task Force Liberty, 3rd Infantry Division, U.S. Army Spc. Jon Paul Fettig — 957th Engineer Company (Multi-Role Bridge)(V Corps), N.D. Army National Guard Capt. John P. Gaffaney — 113th Combat Stress Control Company, 2nd Medical Brigade, U.S. Army Reserve Cpl. Nathan Joel Goodiron — A Battery, 1st Battalion, 188th Air Defense Artillery Regiment (Security Forces), N.D. Army National Guard Pfc. Sheldon R. Hawk Eagle — 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Kenneth W. Hendrickson — 957th Engineer Company (Multi-Role Bridge), 130th Engineer Brigade, Task Force All American, N.D. Army National Guard Spc. Michael Layne Hermanson — A Company, 164th Engineer Battalion, N.D. Army National Guard Spc. James J. Holmes — C Company, 141st Engineer Combat Battalion, N.D. Army National Guard Maj. Alan Ricardo Johnson — A Company, 402nd Civil Affairs Battalion, U.S. Army Reserve Cpl. Christopher Kenneth Kleinwachter — 1st Battalion, 188th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, N.D. Army National Guard Staff Sgt. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

Album: 74Th Troop Carrier Squadron United States Army Air Forces

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl World War Regimental Histories World War Collections 1945 Album: 74th Troop Carrier Squadron United States Army Air Forces Follow this and additional works at: http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his Recommended Citation United States Army Air Forces, "Album: 74th Troop Carrier Squadron" (1945). World War Regimental Histories. 126. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/126 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World War Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in World War Regimental Histories by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .· .· -· ... , ~ .. ; . ,.: ~{::~~~~~~~t-~~r~-~~it1i;,~tiJ@f~~~i~l:f,:t :,: ·,-- ·4· ,... ~ ... '' ' '·.·,: · ,ii~Jj(~~ti~~i:~{:'j ;' DEDICATION This album is respectfully dedicated to the members of the Seventy-Fourth Squadron who were killed in the service of their coun try. They are First Lieutenant Ralph C. Lun gren, Second Lieutenant Leo G. Fitzpatrick. First Lieutenant Weber, Second Lieutenant Link, Second Lieutenant St. Clair X. Hertel, Second Lieutenant T. 0. Ahmad, flight Offi cer Hore, Flight Officer Bean, Flight Officer William A. Heelas, Flight Officer Leonard 0. Hyman, and Captain Harry Bruce. Individual pictures of these men are not available except in the minds of the men who knew them, may this album help perpetu~~ their memory. .FOREWORD Any similarity between this book and an official Army Historical Report is coincidental and unintentional. The written portion is mere ly intended as an outline for your reminiscing. -

The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): a Revolution in Organizational Structure

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations Student Scholarship 12-2020 The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Infrastructure Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Nonprofit Administration and Management Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Adam, "The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure" (2020). Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations. 165. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones/165 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis Capstone paper for Master of Policy, Planning, and Management Program Muskie School of Public Service University of Southern Maine December 2020 Professor Joseph McDonnell, Capstone Advisor THE BRIGADE COMBAT TEAM (BCT) 2 Abstract This paper explores the U.S. Army’s force reorganization around the Brigade Combat Team (BCT), which began in 2002. The BCT shifted how various army units interacted by changing the echelon at which different types of units report to a single commander, essentially creating self-sufficient units of about 2,500 soldiers instead of the previous self-sufficient units of about 15,000 soldiers. -

The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

CHAPTER 2 Department of the Army Overview when the service launched a “modularity” initiative, the The Department of the Army includes the Army’s active Army was organized for nearly a century around divisions component; the two parts of its reserve component, the (which involved fewer but larger formations, with 12,000 Army Reserve and the Army National Guard; and all to 18,000 soldiers apiece). During that period, units in federal civilians employed by the service. By number of Army divisions could be separated into ad hoc BCTs military personnel, the Department of the Army is the (typically, three BCTs per division), but those units were biggest of the military departments. It also has the largest generally not organized to operate independently at any operation and support (O&S) budget. The Army does command level below the division. (For a description of not have the largest total budget, however, because it the Army’s command levels, see Box 2-1.) In the current receives significantly less funding to develop and acquire structure, BCTs are permanently organized for indepen- weapon systems than the other military departments do. dent operations, and division headquarters exist to pro- vide command and control for operations that involve The Army is responsible for providing the bulk of U.S. multiple BCTs. ground combat forces. To that end, the service is orga- nized primarily around brigade combat teams (BCTs)— The Army is distinct not only for the number of ground large combined-arms formations that are designed to combat forces it can provide but also for the large num- contain 4,400 to 4,700 soldiers apiece and include infan- ber of armored vehicles in its inventory and for the wide try, artillery, engineering, and other types of units.1 The array of support units it contains. -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

Commanding an Air Force Squadron in Twenty-First Century

Commanding an Air Force Squadron in the Twenty-First Century A Practical Guide of Tips and Techniques for Today’s Squadron Commander JEFFRY F. SMITH Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2003 Air University Library Cataloging Data Smith, Jeffry F. —Commanding an Air Force squadron in the twenty-first century : a practical guide of tips and techniques for today’s squadron commander / Jeffry F. Smith. —p. ; cm. —Includes bibliographical references and index. —Contents: Critical months—The mission—People—Communicative leadership— The good, the bad and the ugly—Cats and dogs—Your exit strategy. —ISBN 978- 1-58566-119-0 1. United States. Air Force—Officers’ handbooks. 2. Command of troops. I. Title. 358.4/1330/41—dc21 First Printing August 2003 Second Printing September 2004 Third Printing April 2005 Fourth Printing August 2005 Fifth Printing March 2007 Sixth Printng August 2007 Seventh Printing August 2008 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied are solely those of the au- thor and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112–5962 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii To my parents, Carl and Marty Smith, whose example of truth, ethics,and integrity shaped my life. And to my wife Cheryl and sons Stephen and Andrew, whose love, support, and service to our Air Force has been my inspiration to continue to serve. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . -

Military Units Style Contents

Military Units Style - Colors Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Blue Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 1 Military Units Style - Fill Symbols Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 2 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols à Infantry Soldier  Helicopter - AH Apache Å Missile Launcher Æ Frigate Ê Generic Tank Ç Destroyer Ë Enemy Tank È Submarine SSBN Ì B-2 Stealth É Submarine Attack Ó F-14 Tomcat À Torpedo Ô Fighter ß Explosion Õ FA-18 ! Unit Ö F-5 " Headquarters Unit Ù Fighter # Logistics/Admin Installation Ú Fighter $ Theater Ü Generic Fighter % Corps Ò E-3 AWACS & Supply unit Ï Helicopter - CH-46 Chinook ' Squad Ð Helicopter - AH Cobra ( Section/Platoon Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 3 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols ) Platoon/Squadron 8 Infantry Battalion * Company/Battery/Troop 9 Infantry Regiment + Battalion/Squadron : Infantry Brigade , Regiment ; Infantry Division - Brigade < Infantry Corps . Division = Infantry Army / Corps > Infantry Mechanized Squad 0 Army ? Infantry Mechanized Section 1 Infantry @ Infantry Mechanized Platoon 2 Infantry Mechanized A Infantry Mechanized Company 3 Armor B Infantry Mechanized Battalion Company 4 Infantry Squad C Infantry Mechanized Regiment 5 Infantry Section D Infantry Mechanized Brigade 6 Infantry Platoon E Infantry Mechanized Division 7 Infantry Company F Infantry Mechanized Corps Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. -

Fm 1-114 Air Cavalry Squadron and Troop Operations

FM 1-114 AIR CAVALRY SQUADRON AND TROOP OPERATIONS DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PCN 32000075200 *FM 1-114 Field Manual Headquarters No. 1-114 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 1 February 2000 Air Cavalry Squadron and Troop Operations Contents Page PREFACE.......................................................................................................... vii Chapter 1 RECONNAISSANCE AND SECURITY HELICOPTER FUNDAMENTALS............... 1-0 Section I—Primary Roles and Missions.......................................................... 1-0 Essential Characteristics of Army Operations ..................................................... 1-0 Squadron Mission............................................................................................. 1-1 Troop Mission .................................................................................................. 1-2 Capabilities and Limitations ............................................................................... 1-2 Section II—Organizations .............................................................................. 1-3 Cavalry Organizations ....................................................................................... 1-3 Regimental Aviation Squadron ........................................................................... 1-3 Division Cavalry Squadron ................................................................................. 1-4 Air Cavalry Squadron ....................................................................................... -

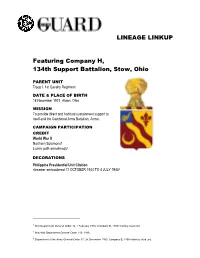

LINEAGE LINKUP Featuring Company H, 134Th Support

LINEAGE LINKUP Featuring Company H, 134th Support Battalion, Stow, Ohio PARENT UNIT Troop I, 1st Cavalry Regiment DATE & PLACE OF BIRTH 18 November 1921, Akron, Ohio MISSION To provide direct and habitual sustainment support to itself and the Combined Arms Battalion, Armor. CAMPAIGN PARTICIPATION CREDIT World War II Northern Solomons1 Luzon (with arrowhead)2 DECORATIONS Philippine Presidential Unit Citation streamer embroidered 17 OCTOBER 1944 TO 4 JULY 19453 1 War Department General Order 12, 1 February 1946. Company B, 145th Infantry cited unit. 2 Ibid; War Department General Order 109, 1946. 3 Department of the Army General Order 47, 28 December 1950. Company B, 145th Infantry cited unit. 1921 Organized and Federally recognized 18 November 1921 in the Ohio National Guard at Akron as Troop I, 1st Cavalry4 1922 Reorganized and redesignated 1 February 1922 as Troop E, 107th Cavalry, an element of the 22d Cavalry Division5 1927 Reorganized and redesignated 1 October 1927 as Headquarters Troop, 54th Cavalry Brigade6 1940 Disbanded 1 November 19407 1948 Reorganized and Federally recognized 16 March 1948 in the Ohio Army National Guard at Akron as Troop E, 107th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron8 1949 Reorganized and redesignated 15 September 1949 as Assault Gun Company, 1st Battalion, 107th Armored Cavalry Regiment9 1959 Redesignated 1 April 1951 as Howitzer Company, 1st Battalion, 107th Armored Cavalry Regiment10 Reorganized and redesignated 1 September 1959 as Troop F, 2d Squadron, 107th Armored Cavalry Regiment11 1961 Location changed 1 December 1961 to Greensburg12 1963 Reorganized and redesignated 1 April 1963 as Troop H, 2d Squadron, 107th Armored Cavalry Regiment13 4 TAGOH General Order 15, 1921.