Packington: Early History - BC to 11Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edwards of Staunton Harold

The Edwards Family of Staunton Harold Descendant Chart for Thomas Edwards Harold Thomas Edwards Frances b: Abt. 1753 in Shakespeare Leicestershire, b: 1754 in England; May not Coleorton, have been born Leicestershire, Leicestershire - England needs further evidence William Edwards Elizabeth Aymes 4 b:Staunton 1775 in b: Abt. 1773 in Coleorton, Coleorton, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, of England England 2 Tivey A EdwardsJ (c) www.tiveyfamilytree.com Page 1 The Edwards Family of Staunton Harold Harold 1 William Edwards Elizabeth Aymes b: 1775 in b: Abt. 1773 in Coleorton, Coleorton, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, England England Mary Edwards Joseph Tivey John Edwards Ann Kinsey Elizabeth Edwards Joseph Fairbrother 3 b: 1795 in b: 1794 in b: 1797 in b: Abt. 1803 in b: Abt. 1800 in b: Abt. 1800 in Coleorton, Derbyshire, Staunton Harold, Swannington, Ropers Hill Farm, Staunton Harold, Leicestershire, England Leicestershire,Staunton Leicestershire, Staunton Harold, Leicestershire, England England England Leicestershire, England England 17 35 of 40 Tivey A EdwardsJ (c) www.tiveyfamilytree.com Page 2 The Edwards Family of Staunton Harold Harold William Edwards Elizabeth Aymes b: 1775 in b: Abt. 1773 in Coleorton, Coleorton, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, England England 2 William Edwards Ann Bailey James Edwards Thomas Edwards Elizabeth Watson b: Abt. 1803 in b: b: Abt. 1805 in b: Abt. 1806 in b: 1803 in Ropers Hill Farm, Ropers Hill Farm, Ropers Hill Farm, Worthington, Staunton Harold, StauntonStaunton Harold, Staunton Harold, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, Leicestershire, England England England England 41 of 42 Tivey A EdwardsJ (c) www.tiveyfamilytree.com Page 3 The Edwards Family of Staunton Harold Thomas Edwards Frances Harold b: Abt. -

A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire First published by English Heritage April 2012 Rebranded by Historic England December 2017 Introduction Leicestershire contains a wide range of distinctive building This is particularly true for the less common stone types. In stone lithologies and their areas of use show a close spatial some parts of the county showing considerable geological link to the underlying bedrock geology. variability, especially around Charnwood and in the north- west, a wide range of lithologies may be found in a single Charnwood Forest, located to the north-west of Leicester, building. Even the cobbles strewn across the land by the includes the county’s most dramatic scenery, with its rugged Pleistocene rivers and glaciers have occasionally been used tors, steep-sided valleys and scattered woodlands. The as wall facings and for paving, and frequently for infill and landscape is formed principally of ancient volcanic rocks, repair work. which include some of the oldest rocks found in England. To the west of Charnwood Forest, rocks of the Pennine Coal The county has few freestones, and has always relied on the Measures crop out around Ashby-de-la-Zouch, representing importation of such stone from adjacent counties (notably for the eastern edge of the Derbyshire-Leicestershire Coalfield. To use in the construction of its more prestigious buildings). Major the north-west of Charnwood lie the isolated outcrops of freestone quarries are found in neighbouring Derbyshire Breedon-on-the-Hill and Castle Donington, which are formed, (working Millstone Grit), Rutland and Lincolnshire (both respectively, of Carboniferous Limestone and Triassic working Lincolnshire Limestone), and in Northamptonshire (Bromsgrove) Sandstone. -

Nominated Candidates for North West Leicestershire District

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED AND NOTICE OF POLL North West Leicestershire Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for the Ashby de la Zouch electoral division of Leicestershire County Council Reason Name of Assentors why no Description Name of Candidate Home Address Proposer(+) longer (if any) Seconder(++) nominated * BENFIELD 98 Market St, Ashby Green Party Benfield Rebecca J S + Carl Cheswick de la Zouch, LE65 Benfield Leon J ++ 1AP COXON Highfield House, 66 The Conservative Hoult Gillian S + John Geoffrey Leicester Road, New Party Candidate Hoult Stanley J ++ Packington, Ashby de la Zouch JACKSON 19 Lakeshore Labour Party Parle Elizabeth J + Debra Louise Crescent, Whitwick, Parle Gregory V ++ Coalville, Leicestershire, LE67 5BZ O`CALLAGHAN (address in North Freedom Alliance. Anslow Judith E + Claire Louise West Leicestershire) No Lockdowns. Haberfield Alison ++ No Curfews. TILBURY (address in North Reform UK Tilbury Lindsay + Adam Rowland West Leicestershire) Woods Paul L ++ WYATT (address in North Liberal Democrat Sedgwick Maxine S + Sheila West Leicestershire) Sedgwick Robert ++ *Decision of the Deputy Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. A POLL WILL BE TAKEN on Thursday 6 May 2021 between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. Where contested this poll is taken together -

North West Leicestershire—Main Settlement Areas Please Read and Complete

North West Leicestershire—Main settlement areas Please read and complete North West Leicestershire District Council - Spatial Planning - Licence No.: 100019329 Reproduction from Ordnance Survey 1:1,250 mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. For further help and advice contact North West Leicestershire Housing Advice Team. Freephone: 0800 183 0357, or e-mail [email protected] or visit our offices at Whitwick Road, Coalville, Leicester LE67 3FJ. Tell us where you would prefer to live Please tick no more than THREE Main Areas you would prefer to live in, then just ONE Sub Area for each main area you select . Please note you will not be restricted to bidding for properties in only these areas Main Area Sub Area (Please select ONLY three) 9 (Please select ONLY one for each 9 main area you have ticked) Ashby–de-la-Zouch Town centre Marlborough Way Northfields area Pithiviers/Wilfred Place Willesley estate Westfields estate (Tick only one) Castle Donington Bosworth Road estate Moira Dale area Windmill estate Other (Tick only one) Coalville Town centre Agar Nook Avenue Road area Greenhill Linford & Verdon Crescent Meadow Lane/Sharpley Avenue Ravenstone Road area 2 (Tick only one) Ibstock Town centre Central Avenue area Church View area Deepdale area Leicester Road area (Tick only one) Kegworth Town centre Jeffares Close area Mill Lane estate Thomas Road estate (Tick only one) Measham Town centre -

History of Mens County Competitions

Bowls Leicestershire BE Founder Member 2008 ✺ Unified County Formed 2013 HISTORY OF MENS COUNTY COMPETITIONS These details are the ongoing attempt to keep a permanent web record of the competition history of the men bowlers of Leicestershire. It is obviously incomplete and if you can supply any details that are missing eg the full names of winners of any of the team competitions listed from your club records, please email [email protected]. It would also be very good if you had any photos of the winners. We would like to feature them occasionally on the website. With the introduction of Bowls Leicestershire as a unified county in 2013, the Leicestershire Bowling Association became the Men’s Section of Bowls Leicestershire. These records are inclusive of LBA records. The sections run as follows: County Championship Winners – Singles, Pairs, Triples Fours, 2 wd Singles, Under 25 Singles County Championship Runners Up – Singles, Pairs, Triples Fours, 2 wd Singles, Under 25 Singles County Competition Winners – 2 Wood Triples, Over 60 Pairs, Over 60 Singles, Champion of Champions, Secretaries Cup County Competition Runners-Up – 2 Wood Triples, Over 60 Pairs, Over 60 Singles, Champion of Champions, Secretaries Cup County Competition Winners – Club Championship, Greenwood Cup, Unbadged The Leicestershire Bowling Association (LBA) was founded in 1921 and affiliated to English Bowling Association (EBA) prior to the creation of Bowls England. LEICESTERSHIRE MENS Competition History COUNTY CHAMPIONSHIP WINNERS Year Singles Pairs Triples -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Launde Priory 1

21 MAY 2018 LAUNDE PRIORY 1 actswilliam2henry1.wordpress.com Release date Version notes Who Current version: H1-Launde-2018-1 21/5/2018 Original version DXC Previous versions: — — — — This text is made available through the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs License; additional terms may apply Authors for attribution statement: Charters of William II and Henry I Project David X Carpenter, Faculty of History, University of Oxford LAUNDE PRIORY Augustinian priory of St John the Baptist County of Leicestershire : Diocese of Lincoln Founded 1121 × c. 1125 Launde priory was one of the early Augustinian houses in England, established 1120 × c. 1125. According to a narrative concerning the early years of Holy Trinity priory in Aldgate, London, known only from fifteenth-century manuscripts, Bernard prior of Dunstaple, John prior of Launde (Landa), Geoffrey de Clinton, the (king’s) chamberlain (Gaufridus camerarius de Clinton), and others named, witnessed the gift of the Cnihtengild in London to Holy Trinity in that year. It is unsurprising that the priors of two recently founded Augustinian houses should witness a gift to Holy Trinity, thought to be the first Augustinian house in England. Their names were presumably taken from a contemporary deed or other record which has not been preserved (Hodgett, Cartulary of Holy Trinity, 168, no. 871; R. R. Sharpe, Calendar of Letter Books, C, 220). The king’s confirmation of the gift, 000, Regesta 1467, also witnessed by Geoffrey de Clinton, is apparently authentic and datable 1123 × 1127, so the narrative’s date of 1125 may well be accurate. Launde priory was founded at Loddington, ‘in cuius territorio abbatia fundata est’, according to Henry II’s general confirmation of 1155 × 1158 (H2/1456). -

HS2 Ltd ‘2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement’ Consultation Response of Leicestershire County Council December 2018

HS2 Ltd ‘2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement’ Consultation Response of Leicestershire County Council December 2018 Structure of this response This Response to the HS2 Ltd Working Draft Environmental Statement (WDES) by is split into four parts. These are as follows: PART 1: Document Introduction and Main areas of Concern PART 2: Response to WDES Vol 2 – Community Areas LA03, LA04 and LA05 PART 3: Response to WDES Vol 2 – Route-wide Effects PART 4: Response to WDES Vol 3 – Off-route Effects PART 5: Appendices For any enquires about this response, please contact: [email protected] 1 | Page PART 1: Document Introduction and Maim areas of Concern i) This document and its appendices comprise Leicestershire County Council’s (the Council’s) response to the Working Draft Environmental Statement (WDES) for HS2 Phase 2b (the proposed scheme). We issue this response in the spirit of contributing to the processes surrounding this vast infrastructure project, but must include the caveat that the Council can only respond to the material to hand and further intensive work with HS2 Ltd is required to fully understand the impacts for Leicestershire and the most appropriate mitigation. ii) The Council recognises that the WDES is a draft document. However, it is disappointing that even in draft; there is a distinct lack of information provided in sections of the WDES, especially regarding the proposed scheme’s constructional and operational impacts and in respect of its design. But, the Council have determined to use this as an opportunity to shape the design and mitigation across the County. Where clear mitigation is not yet defined, the Council will seek to secure assurances from HS2 Ltd that further work will be carried out to inform the preparation of the Hybrid Bill, including HS2 Ltd preparing an Interim Transport Assessment (including sensitivity testing), and during the Parliamentary processes. -

For a Free Valuation of Your Property with No Obligation Call Sinclair Coalville on 01530 838338

20 Vicarage Close, Newbold Coleorton, Leicestershire, LE67 8PG £179,950 01530 838338 sinclairestateagents.co.uk Property at a glance • Spacious Living Room • Extended Conservatory • Fitted Bedrooms • Front & Rear Gardens • Driveway & Garage • No Upward Chain • Council Tax Band*: C • Price: £179,950 Overview ** A WELL PRESENTED AND SPACIOUS TWO BEDROOM DETACHED BUNGALOW LOCATED AT THE END OF A QUIET CUL-DE-SAC IN THE DESIRABLE VILLAGE OF NEWBOLD COLEORTON. AN INTERNAL INSPECTION COMES HIGHLY ADVISED IN ORDER TO APPRECIATE THE EXISTING ACCOMMODATION. ** EPC RATING E. The bungalow in brief comprises entrance hall, three piece bathroom, two bedrooms with fitted wardrobes, spacious living room measuring in excess of 17'0", extended conservatory and kitchen. Externally the property benefits from low maintenance gardens to the front and rear, driveway parking for multiple vehicles leading to a single garage. Additional benefits include double glazing and oil central heating system. Furthermore the property is offered with no upward chain. Location** Newbold Coleorton is a hamlet in the parish of Worthington, Leicestershire. The village has around 250 houses, a primary school, Cross Keys local pub, village park and home to a significant landmark of the once working Newbold Brickworks Chimney. Newbold was a mining village which closed in 1968 and now replaced by ‘New Lount Nature Reserve’ which is a 48 acre site within the National Forest and a very pleasant place for a leisurely walk amongst the wildlife. Nearest Airport: East Midlands (7.2 miles). Nearest Train Station: Loughborough (11.3 miles). Nearest Town/City: Ashby-de-la-Zouch (3.9 miles). Nearest Motorway Access: M1 (J23) A/M42 (J13) ** Distances have been taken from Google maps and are shown as shortest distance by road. -

The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the Family, the Fief and the Feudal Monarchy*

© K.S.B. Keats-Rohan 1991. Published Nottingham Mediaeval Studies 36 (1992), 42-78 The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the family, the fief and the feudal monarchy* In memoriam R.H.C.Davis 1. The Problem (i) the non-Norman Conquest Of all the available studies of the Norman Conquest none has been more than tangentially concerned with the fact, acknowledged by all, that the regional origin of those who participated in or benefited from that conquest was not exclusively Norman. The non-Norman element has generally been regarded as too small to warrant more than isolated comment. No more than a handful of Angevins and Poitevins remained to hold land in England from the new English king; only slightly greater was the number of Flemish mercenaries, while the presence of Germans and Danes can be counted in ones and twos. More striking is the existence of the fief of the count of Boulogne in eastern England. But it is the size of the Breton contingent that is generally agreed to be the most significant. Stenton devoted several illuminating pages of his English Feudalism to the Bretons, suggesting for them an importance which he was uncertain how to define.1 To be sure, isolated studies of these minority groups have appeared, such as that of George Beech on the Poitevins, or those of J.H.Round and more recently Michael Jones on the Bretons.2 But, invaluable as such studies undoubtedly are, they tend to achieve no more for their subjects than the status of feudal curiosities, because they detach their subjects from the wider question of just what was the nature of the post-1066 ruling class of which they formed an integral part. -

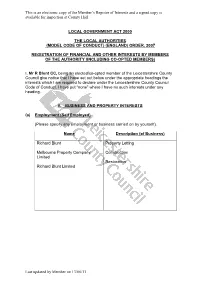

This Is an Electronic Copy of the Member's Register of Interests And

This is an electronic copy of the Member’s Register of Interests and a signed copy is available for inspection at County Hall. LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 2000 THE LOCAL AUTHORITIES (MODEL CODE OF CONDUCT) (ENGLAND) ORDER, 2007 REGISTRATION OF FINANCIAL AND OTHER INTERESTS BY MEMBERS OF THE AUTHORITY (INCLUDING CO-OPTED MEMBERS) I, Mr R Blunt CC, being an elected/co-opted member of the Leicestershire County Council give notice that I have set out below under the appropriate headings the interests which I am required to declare under the Leicestershire County Council Code of Conduct. I have put “none” where I have no such interests under any heading. A. BUSINESS AND PROPERTY INTERESTS (a) Employment (Self Employed) (Please specify any employment or business carried on by yourself). Name Description (of Business) Richard Blunt Property Letting Melbourne Property Company Construction Limited Restoration Richard Blunt Limited Last updated by Member on 13/06/11 This is an electronic copy of the Member’s Register of Interests and a signed copy is available for inspection at County Hall. (b) Employment (Company interests) (Please specify the name of any person who employs or appointed you, the name of any firm in which you are a partner and the name of any company for which you are a remunerated director). Name of Person or Body Description (i.e. Employee, Partner, Director) Melbourne Property Co.Ltd Director Richard Blunt Ltd Director (c) Interests in Securities (Please specify the name of any corporate body which has a place of business or land in the authority’s area and in which you have a beneficial interest in a class of securities of that body that exceeds the nominal value of £25,000 (i.e. -

URBAN GRASSS Programmed Cut Dates for Cut 3 of the Season Our Gangs Aim to Get to the Area Within 5 Working Days of the Planned Cut Date

URBAN GRASSS Programmed Cut Dates for Cut 3 of the Season Our gangs aim to get to the area within 5 working days of the planned cut date. We are currently on programme. Parish / Town Planned Cut 3 Date Ab Kettleby 25/06/2018 Acresford 02/07/2018 Albert Village (inc Spring Cottage) 04/07/2018 Allexton 28/06/2018 Anstey Cut by Parish Council Appleby Magna & Parva 27/06/2018 Arnesby 22/06/2018 Asfordby (inc Asfordby Valley) 26/06/2018 Asfordby Hill 27/06/2018 Ashby de la Zouch (Zone 1) 08/06/2018 Ashby de la Zouch (Zone 2) 11/06/2018 Ashby de la Zouch (Zone 3) 12/06/2018 Ashby de la Zouch (Zone 4) 13/06/2018 Ashby Folville 04/07/2018 Ashby Magna 15/06/2018 Ashby Parva 15/06/2018 Aston Flamville 04/07/2018 Bagworth 18/06/2018 Bardon inc Bardon Industrial Estate 08/06/2018 Barkby and Barkbythorpe Cut by Parish Council Barkstone le vale 12/06/2018 Barlestone 19/06/2018 Barrow on Soar Zone 1 20/06/2018 Barrow on Soar Zone 2 21/06/2018 Barsby 04/07/2018 Barton in the Beans 21/06/2018 Barwell 04/07/2018 Battram 19/06/2018 Beeby 04/07/2018 Belton 04/07/2018 Belvoir Cut by Parish Council Billesdon 14/06/2018 Birstall Zone 1 02/07/2018 Birstall Zone 2 03/07/2018 Bitteswell and Bittesby Cut by Parish Council Blaby 19/06/2018 Blackfordby 04/07/2018 Blaston 29/06/2018 Blood Hill (Kirby Muxloe) 12/06/2018 Botcheston 18/06/2018 Bottesford Zone 1 11/06/2018 Bottesford Zone 2 08/06/2018 Boundary 04/07/2018 Branston 15/06/2018 Braunstone Town 08/06/2018 Breedon on the Hill Cut by Parish Council Brentingby 20/06/2018 Bringhurst 29/06/2018 Brooksby 22/06/2018