Hunterston Parc, North Ayrshire Socio Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunterston Site Stakeholder Group Summary of Key Points from the Fifty Sixth Meeting Held on Thursday 5 March 2020 at the Waterside Hotel, West Kilbride, Ka23 9Ng

HUNTERSTON SITE STAKEHOLDER GROUP SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS FROM THE FIFTY SIXTH MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 5 MARCH 2020 AT THE WATERSIDE HOTEL, WEST KILBRIDE, KA23 9NG Chair’s Opening Remarks and Vice Chair Updates and Correspondence The Chair was disappointed in the NDA’s decision, based on advice from BEIS, not to let the Site Stakeholder Group meeting in December 2019 go ahead due to the upcoming general election, meaning there had been no meeting for six months. During that time, two very important issues were ongoing – Hunterston B Reactor 3 and Reactor 4 Safety Cases and the implementation of REPPIR 2019. The Chair and Vice Chair attended the Scottish Sites meeting in Edinburgh on 31 October 2019. Mrs Holmes attended the annual Magnox SSG Chair and Vice Chairs meeting in London on 23/24 January 2020. Actions and Approval of Previous Minutes The Minutes of the meeting of 5 September 2019 were approved. Hunterston A Site Reports Hunterston A Report – Mr John Grierson The site’s Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR) remains at zero. The site successfully demonstrated two contingency exercises with both being rated green and providing learning points. Focus groups are being set up through the Mental Health and Wellbeing Initiative. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) improvements are being assessed through analysis of surveys. The site will move to a 4 day/wk (from 4.5 days/wk) from April 2020. Deplanting is moving on in the ponds. The SAWBR project is slower than anticipated due to various challenges. Updates were given on SILWE and WILWREP plants. -

Download the Hunterston Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan

OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION Hunterston B Nuclear Power Station Off-site Contingency Plan Prepared by Ayrshire Civil Contingencies Team on behalf of North Ayrshire Council For the West of Scotland Regional Resilience Partnership WAY – No. 01 (Rev. 4.0) Plan valid to 21 May 2020 OFFICIAL SENSITIVE OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION 1.3 Emergency Notification – Information Provided When an incident occurs at the site, the on site incident cascade will be implemented and the information provided by the site will be in the form of a METHANE message as below: M Major Incident Yes / No Date Time E Exact Location Wind Speed Wind Direction T Type Security / Nuclear / etc H Hazards Present or suspected Radiological plume Chemical Security / weapons Fire A Access Details of the safe routes to site RVP N Number of casualties / Number: missing persons Type: Severity E Emergency Services Present or Required On arrival, all emergency personnel will be provided with a dosimeter which will measure levels of radiation and ensure that agreed limits are not reached. Emergency Staff should report to the site emergency controller (see tabard in Section 17.5). Scottish Fire and Rescue will provide a pre-determined attendance of 3 appliances and 1 Ariel appliance incorporating 2 gas suits. In addition to this Flexi Duty Managers would also be mobilised. A further update will be provided by the site on arrival. WAY – No. -

Early Learning and Childcare Guide

Introduction This booklet aims to provide you with information about the changes that are happening to early learning and childcare in North Ayrshire. In August 2020 the annual entitlement to early learning and childcare will be 1140 hours for all three and four year olds and eligible two-year olds. Parents have the choice to use their early learning and childcare (ELC) entitlement at any local authority or funded provider* meeting the National Standards. There is a full list of local authority and funded providers at Appendix 2 and on the CARIS website: www.families.scot Throughout this document the terms: • Parent refers to both parents and carers. • Funded provider refers to local authority, private and voluntary providers, and childminders that are in contract to deliver ELC on behalf of the Council. 2 Your Questions Answered What does this mean for me? You will be entitled to 1140 hours of ELC if you have a child aged 3-5 years. You could also be entitled to this is you have a 2-year-old child and you meet certain eligibility criteria which is detailed on Page 8. You will be entitled to either 30 hours per week over term time (38 weeks) or 23.75 hours per week over the full year (48 weeks) or 28.5 hours over 40 weeks. You can choose to take this in different ways – over full days/half days, or a combination of both, or a blended model over two providers. How will the funded sessions work? To meet the needs of our families and carers there will be three models of delivery available in North Ayrshire Council ELC establishments. -

585A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

585A bus time schedule & line map 585A Ardrossan View In Website Mode The 585A bus line (Ardrossan) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ardrossan: 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM (2) Largs: 6:53 PM - 9:35 PM (3) Stevenston: 7:16 PM - 9:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 585A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 585A bus arriving. Direction: Ardrossan 585A bus Time Schedule 49 stops Ardrossan Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Laverock Drive, Largs Burnside Way, Largs Tuesday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Laverock Drive, Largs Wednesday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Douglas Place, Largs Thursday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Friday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Noddleburn Road, Largs Saturday 6:39 PM - 10:35 PM Douglas Street, Largs Brisbane Street, Largs Brooksby House, Largs 585A bus Info Direction: Ardrossan School Street, Largs Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 37 min Gallowgate Street, Largs Line Summary: Laverock Drive, Largs, Laverock Manse Court, Largs Drive, Largs, Douglas Place, Largs, Noddleburn Road, Largs, Douglas Street, Largs, Brisbane Street, Largs, Manse Court, Largs Brooksby House, Largs, School Street, Largs, Manse Gogo Street, Largs Court, Largs, Gogo Street, Largs, Lovat Street, Largs, Bankhouse Avenue, Largs, Springƒeld Gardens, Townhead Close, Largs Largs, Largs Golf Course, Largs, Marina, Largs, Lovat Street, Largs Kelburn Avenue, Fairlie, Kelburn Avenue, Fairlie, Pier Road, Fairlie, School Brae, Fairlie, The Causeway, Bankhouse Avenue, Largs Fairlie, Burnfoot Road, Fairlie, -

Hunterston Site Stakeholder Group Summary of Key

HUNTERSTON SITE STAKEHOLDER GROUP SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS FROM THE FIFTY FIFTH MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 5 SEPTEMBER 2019 AT THE WATERSIDE HOTEL, WEST KILBRIDE, KA23 9NG Chair’s Opening Remarks and Vice Chair Updates and Correspondence A Socio-Economic Presentation by Caitriona McAuley of North Ayrshire Council had been given to voting members at 11.30 am that day to allow more time for other agenda items. The Chair’s report on the NDA Summit on 9/10 July 2019 was circulated with meeting papers. Mrs Holmes updated on a Site End State meeting held on 28 August 2019. The purpose of the meeting was to plan the route of the end state and the meeting was very informative, with examples given. The meeting gave an opportunity for discussion and further and wider consultation is planned for the future. Actions and Approval of Previous Minutes The Minutes of the meeting of 6 June 2019 were approved. North Ayrshire Civil Contingencies – REPPIR Presentation – Ms Jane McGeorge Ms McGeorge gave an overview of the duties placed on EDF Energy and on North Ayrshire Council, as duty holder, in respect of The REPPIR 2019 Act, which was laid in Parliament on 27 March, became statute on 22 May 2019 and has an implementation period of 12 months. A Plan must be in place by 22 May 2020. Hunterston A Site Reports Hunterston A Report – Mr John Grierson and Mr Ian Warner The site’s Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR) remains at zero. The push on Target Zero remains with the Go Home Safe Every Day message. -

Hunterston Habits Repost

Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 1 Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 Authors and Contributors: I. Dale; P. Smith; A. Tyler; D. Copplestone; A. Varley; S. Bradley; P Bartie; M. Clarke and M. Blake External Reviewer: A. Elliot 2 Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 This page has been left blank intentionally blank 3 Radiological Habits Survey: Hunterston 2017 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................... 4 List of Abbreviations and Definitions ..................................................................................... 9 Units ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Summary ............................................................................................................................ 10 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 14 1.1 Regulatory Context .................................................................................................. 14 1.2 Definition of the Representative Person ................................................................... 15 1.3 Dose Limits and Constraints .................................................................................... 16 1.4 -

Upper Cottage, Hunterston Estate, West Kilbride Ka23 9Qg

UPPER COTTAGE, HUNTERSTON ESTATE, WEST KILBRIDE KA23 9QG £525 per month, Unfurnished UPPER COTTAGE, HUNTERSTON ESTATE, WEST KILBRIDE Rural location LP gas central heating Maximum of 2 pets No garden ground Landlord Registration: 37916/310/21460 EPC Rating = D Council Tax = B A first floor apartment forming part of an attractive residential courtyard in the grounds of Hunterston Estate. Situation Situated about 2 miles from the craft town of West Kilbride and coastal resort of Seamill with its famous Hydro, and Largs which is about 6 miles to the north. The train station at West Kilbride provides a regular service to Glasgow. The regular ferry services to the Clyde islands of Arran and Great Cumbrae are located at Ardrossan and Largs. Accommodation Timber partially glazed front door opens into: Hall 5.25m x 0.98m. With store cupboard housing the central heating boiler, radiator, 2 power points and doors off to: Bathroom 3.50m x 1.44m. Bath with electric shower over, multiwall panelling and shower screen, wash hand basin and WC. Radiator. Vinyl flooring. Bedroom 1 4.12m x 2.99m. Shelved cupboard with hanging rail. Radiator and 4 power points. Bedroom 2 3.82m x 3.57m. Radiator, 4 power points and telephone socket. Open plan Living Room / Kitchen 5.33m x 4.84m and 3.09m x 2.47m. The living room has an inset electric fire, 2 radiators and 6 power points. The fitted kitchen area comprises a range of floor and wall units with splashback and incorporating an electric oven with extractor hood over, single stainless steel sink and drainer, space and plumbing for a washing machine and space for a full height fridge/freezer. -

Hunterston Construction Yard Environmental Review

Hunterston Construction Yard Environmental Review February 2017 Hunterston Construction Yard Environmental Review Client: Peel Ports Document number: 7467 Project number: 168612 Status: For Issue Redacted Author: Reviewer: Date of issue: 9 February 2017 Glasgow Aberdeen Inverness Edinburgh Craighall Business Park Banchory Business Alder House Suite 114 8 Eagle Street Centre Cradlehall Business Park Gyleview House Glasgow Burn O’Bennie Road Inverness 3 Redheughs Rigg G4 9XA Banchory IV2 5GH Edinburgh 0141 341 5040 AB31 5ZU 01463 794 212 EH12 9DQ [email protected] 01330 826 596 0131 516 9530 www.envirocentre.co.uk This report has been prepared by EnviroCentre Limited with all reasonable skill and care, within the terms of the Contract with Peel Ports (“the Client”). The report is confidential to the Client, and EnviroCentre Limited accepts no responsibility of whatever nature to third parties to whom this report may be made known. No part of this document may be reproduced or altered without the prior written approval of EnviroCentre Limited. Peel Ports February 2017 Hunterston Construction Yard; Environmental Review Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Site Location ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Scope of This Document......................................................................................................................... -

Proposed Local Development Plan

April 2018 Proposed Local Development Plan Your Plan Your Future Your Plan Your Future Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................. 2 Using the Plan ...................................................................................................................4 What Happens Next ...................................................................................................... 5 page 8 page 18 How to Respond .............................................................................................................. 5 Vision .....................................................................................................................................6 Strategic Policy 1: Spatial Strategy ....................................................................... 8 Strategic Policy 1: Strategic Policy 2: Towns and Villages Objective .............................................................................. 10 The Countryside Objective ....................................................................................12 The Coast Objective ..................................................................................................14 Spatial Placemaking Supporting Development Objective: Infrastructure and Services .....16 Strategy Strategic Policy 2: Placemaking ........................................................................... 18 Strategic Policy 3: Strategic Development Areas .....................................20 -

North Ayrshire Council

North Ayrshire Council A Meeting of North Ayrshire Council will be held remotely on Wednesday, 16 December 2020 at 14:00 to consider the undernoted business. Arrangements in Terms of COVID-19 In light of the current COVID-19 pandemic, this meeting will be held remotely in accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 2003. Where possible, the meeting will be live-streamed and available to view at https://north-ayrshire.public- i.tv/core/portal/home. In the event that live-streaming is not possible, a recording of the meeting will instead be available to view at this location. 1 Apologies 2 Declarations of Interest Members are requested to give notice of any declarations of interest in respect of items of business on the Agenda. 3 Previous Minutes The accuracy of the Minutes of the Meeting held on 11 November 2020 will be confirmed and the Minutes signed in accordance with Paragraph 7(1) of Schedule 7 of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 (copy enclosed). 4 Provost's Report Submit the Provost's report for the period covering 2 November - 6 December 2020 (copy enclosed). 5 Leader's Report Submit report by the Leader of the Council covering the period 2 November - 6 December 2020 (copy enclosed). North Ayrshire Council, Cunninghame House, Irvine KA12 8EE 1 6 Minute Volume (issued under separate cover) Submit, for noting and for approval of any recommendations contained therein, the Minutes of Meeting of committees of the Council held in the period 4 September - 2 December 2020. 7 Annual Review of Governance Documentation Submit report by the Chief Executive on the key Governance documentation regulating the operation of Council, its committees and officers (copy enclosed). -

Hunterston Off-Site Plan

OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION Hunterston B Nuclear Power Station Off-site Contingency Plan Prepared by Ayrshire Civil Contingencies Team on behalf of North Ayrshire Council For the West of Scotland Regional Resilience Partnership WAY – No. 01 (Rev. 5.3 - Accessible) (Reviewed Feb 2021) Plan valid to May 2023 OFFICIAL SENSITIVE OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION PART 1: EMERGENCY NOTIFICATIONS AND PROCEDURES 1.1 Emergency Notification – Site Incident When an incident occurs the Hunterston Power Station Emergency Controller (or nominated deputy) will use the cascade charts below (in conjunction with the telephone numbers in Section 1.4) to alert relevant organisations who will then cascade the information further as per the cascade. This section of the plan has been redacted WAY – No. 01 (Rev. 5.3 - Accessible) (Reviewed Feb 2021) Plan valid to May 2023 2 OFFICIAL SENSITIVE OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION 1.2 Emergency Notification – Off-site Nuclear Emergency When an off-site nuclear emergency incident occurs the Hunterston Power Station Emergency Controller will use the cascade charts below (in conjunction with the telephone numbers in Section 1.4) to alert relevant organisations who will then cascade the information further as per the cascade below. Once alerted, each agency will send a representative to the HSCC at This section of the plan has been redacte. A test (Exercise Busby) is carried out on an annual basis to ensure that the information supplied is still current. -

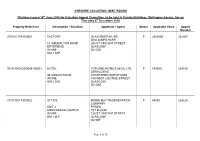

Property Reference Description / Situation Appellant / Agent Status Appealed Value Appeal Number

AYRSHIRE VALUATION JOINT BOARD Citations Issued 16th June 2016 for Valuation Appeal Committee, to be held in County Buildings, Wellington Square, Ayr on Thursday 8th December 2016 Property Reference Description / Situation Appellant / Agent Status Appealed Value Appeal Number 07/01/C47340/0051 FACTORY GLAXOSMITHKLINE P 2502000 234267 GVA JAMES BARR 51 SHEWALTON ROAD 206 ST VINCENT STREET DRYBRIDGE GLASGOW IRVINE G2 5SG KA11 5AP 07/01/D01620/0046 /00001 HOTEL TOPLAND HOTELS (NO2) LTD P 190000 234516 GERALD EVE 46 ANNICK ROAD CHARTERED SURVEYORS IRVINE 140 WEST GEORGE STREET KA12 0JG GLASGOW G2 2HG 07/01/D01730/0002 OFFICE IRVINE BAY REGENERATION P 45000 234220 COMPANY UNIT 2 RYDEN ANNICKBANK CAMPUS 1ST FLOOR IRVINE 130 ST VINCENT STREET KA11 4LF GLASGOW G2 5HF Page 1 of 75 AYRSHIRE VALUATION JOINT BOARD Citations Issued 16th June 2016 for Valuation Appeal Committee, to be held in County Buildings, Wellington Square, Ayr on Thursday 8th December 2016 Property Reference Description / Situation Appellant / Agent Status Appealed Value Appeal Number 07/01/D01730/0003A OFFICE ACCESS PLUS (SCOTLAND) LTD T 52000 234360 RYDEN ROSEMOUNT HOUSE 1ST FLOOR ANNICKBANK CAMPUS 130 ST VINCENT STREET IRVINE GLASGOW KA11 4LF G2 5HF 07/01/D01730/0003B OFFICE ROSEMOUNT HOLDINGS P 16400 234368 MOIRA WALKER ROSEMOUNT HOUSE (GL) RYDEN ANNICKBANK CAMPUS 130 ST VINCENT STREET IRVINE GLASGOW KA11 4LF G2 5HF 07/01/D02280/0028 /U0004 SHOP PIRGIN SINGH PAVITA P 12900 234237 SHERGILL Unit 4 & MRS GURMEJ KAUR 28 BANK STREET IRVINE KA12 0AD Page 2 of 75 AYRSHIRE VALUATION