An Analysis of Socioemotional and Task Communication in Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issn 2320-9186 1668

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 8, August 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 1668 GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 8, August 2020, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com Theoretical overview of playing multiplayer video game using EEG device (Neuro Sky Mobile 2) DR. ASHRAF UDDIN,MD.SHAID HASAN PRANTO, ERSHADUL ALAM SEZAN,ABDUS SALAM NIHAL,MOSTAFIZ SHOVON ABSTRACT In this paper we proposed a multiplayer number picker game using brain computer interface (BCI). This game will be controlled by at least two or more people using NeuroSky MindWave Mobile 2. The users will advance through the game by choosing numbers through their brain. Our assumption is the game can be played by both able body or people with disability or both. This will be a simple game which may determine people’s impression and maybe helpful to other Electroencephalography (EEG) based brain computer interface devices to perform multi computational task from multiple users. In our paper we have examined different paper on BCI process using EEG devices that enabled us to learn more about multiplayer gaming advantages in the field of brain computer interface (BCI). 1. INTRODUCTION In brain computer interface it offers a non-invasive means of enabling a human to send messages and commands directly from his or her brain to a computer without moving or by wearing a simple scalp probe. Brain computer interface (BCI) provide the brain with the new output channels that depends on brain activity rather that on peripheral nerves and muscles. BCI can for example provide communication and control, in which the users intent is decoded from electrophysiological measures of brain activity. -

Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game Chat Project

[Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game Chat] 175 Lakeside Ave, Room 300A Phone: (802)865-5744 Fax: (802)865-6446 1/21/2016 http://www.lcdi.champlain.edu Disclaimer: This document contains information based on research that has been gathered by employee(s) of The Senator Patrick Leahy Center for Digital Investigation (LCDI). The data contained in this project is submitted voluntarily and is unaudited. Every effort has been made by LCDI to assure the accuracy and reliability of the data contained in this report. However, LCDI nor any of our employees make no representation, warranty or guarantee in connection with this report and hereby expressly disclaims any liability or responsibility for loss or damage resulting from use of this data. Information in this report can be downloaded and redistributed by any person or persons. Any redistribution must maintain the LCDI logo and any references from this report must be properly annotated. Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Background: ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Purpose and Scope: ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Research Questions: ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Platf Orm Game First Person Shooter Strategy Game Alternatereality Game

First person shooter Platform game Alternate reality game Strategy game Platform game Strategy game The platform game (or platformer) is a video game genre Strategy video games is a video game genre that emphasizes characterized by requiring the player to jump to and from sus- skillful thinking and planning to achieve victory. They empha- pended platforms or over obstacles (jumping puzzles). It must size strategic, tactical, and sometimes logistical challenges. be possible to control these jumps and to fall from platforms Many games also offer economic challenges and exploration. or miss jumps. The most common unifying element to these These games sometimes incorporate physical challenges, but games is a jump button; other jump mechanics include swing- such challenges can annoy strategically minded players. They ing from extendable arms, as in Ristar or Bionic Commando, are generally categorized into four sub-types, depending on or bouncing from springboards or trampolines, as in Alpha whether the game is turn-based or real-time, and whether Waves. These mechanics, even in the context of other genres, the game focuses on strategy or tactics. are commonly called platforming, a verbification of platform. Games where jumping is automated completely, such as The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, fall outside of the genre. The platform game (or platformer) is a video game genre characterized by requiring the player to jump to and from sus- pended platforms or over obstacles (jumping puzzles). It must be possible to control these jumps and to fall from platforms or miss jumps. The most common unifying element to these games is a jump button; other jump mechanics include swing- ing from extendable arms, as in Ristar or Bionic Commando, or bouncing from springboards or trampolines, as in Alpha Waves. -

Video Games and English As a Second Language •

Video Games and English as a Second Language The Effect of Massive Multiplayer Online Video Games on the Willingness to Communicate and Communicative Anxiety of College Students in Puerto Rico • Kenneth S. Horowitz The informal setting of online multiplayer video games may offer safe spots for speakers of other languages learning English to practice their communi- cation skills and reduce their anxiety about using a second language. In this study, the author examined the relationship between both these concerns and the time spent playing such games by basic and intermediate English-as-a- second-language (ESL) college students in Puerto Rico. The results indicated a statistically significant relationship between them, supporting previous studies that establish a relationship between online multiplayer video game play and increased confidence and lowered anxiety about using English among second-language learners. Key words: affective filter; communica- tive anxiety (CA); English as a second language (ESL); massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG); willingness to communicate (WTC) As technology improves and online connectivity pervades many aspects of daily life, the ability to interact with others online grows more and more common- place. Text messaging and the use of social media have become standard means of communication for many individuals, and this level of connectivity carries over to video games. Online multiplayer video gaming is more popular now than ever before, thanks in part to the incredible strides game consoles and home computers have achieved in making online interactions smooth and acces- sible. More than half of those who play video games (53 percent) do so with others, spending more than six hours per week playing online (ESA 2017). -

Character Balance in MOBA Games

Character Balance in MOBA Games Faculty of Arts Department of Game Design Authors: Emanuel Palm, Teodor Norén Bachelor’s Thesis in Game Design, 15 hp Program: Game Design and Programming Supervisors: Jakob Berglund Rogert, Masaki Hayashi Examiner: Mikael Fridenfalk June, 2015 Abstract As live streaming of video games has become easier, electronic sports have grown quickly and they are still increasing as tournaments grow in viewers and prizes. The purpose of this paper is to examine the theory Metagame Bounds by applying it to League of Legends and Dota 2, to see if it is a valid way of looking at character balance in the Multiplayer Online Battle Arena game genre. The main mode of both games consist of matches played on a map where a team of five players is up against another team of five players. Characters in the games generally have four abilities and a number of attributes, making them complex to compare without context. We gathered character data from websites and entered the data into a file that we used with the Metagame Bounds application. We compared the graphs that the data yielded with how often a character wins and how often it is played. To examine whether the characters were balanced we also played the games and analysed the characters in depth. All statistical data gathered was retrieved over the span of a few hours on the 21st of April 2015 from the websites Champion.gg for League of Legends and Dotabuff for Dota 2. Sirlin’s (2001) definition of multiplayer game balance is “A multiplayer game is balanced if a reasonably large number of options available to the player are viable – especially, but not limited to, during high-level play by expert players.” and with the data we see that these games are balanced in terms of characters according to that definition. -

HOW to PLAY with MAPS by Ross Thorn Department of Geography, UW-Madison a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Require

HOW TO PLAY WITH MAPS by Ross Thorn Department of Geography, UW-Madison A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Cartography) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2018 i Acknowledgments I have so many people to thank for helping me through the process of creating this thesis and my personal development throughout my time at UW-Madison. First, I would like to thank my advisor Rob Roth for supporting this seemingly crazy project and working with me despite his limited knowledge about games released after 1998. Your words of encouragement and excitement for this project were invaluable to keep this project moving. I also want to thank my ‘second advisor’ Ian Muehlenhaus for not only offering expert guidance in cartography, but also your addictive passion for games and their connection to maps. You provided endless inspiration and this research would not have been possible without your support and enthusiasm. I would like to thank Leanne Abraham and Alicia Iverson for reveling and commiserating with me through the ups and downs of grad school. You both are incredibly inspirational to me and I look forward to seeing the amazing things that you will undoubtedly accomplish in life. I would also like to thank Meghan Kelly, Nick Lally, Daniel Huffman, and Tanya Buckingham for creating a supportive and fun atmosphere in the Cartography Lab. I could not have succeeded without your encouragement and reminder that we all deserve to be here even if we feel inadequate. You made my academic experience unforgettable and I love you all. -

A First Look at Private Communications in Video Games Using Visual Features

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies ; 2021 (3):433–452 Abdul Wajid, Nasir Kamal, Muhammad Sharjeel, Raaez Muhammad Sheikh, Huzaifah Bin Wasim, Muhammad Hashir Ali, Wajahat Hussain, Syed Taha Ali*, and Latif Anjum A First Look at Private Communications in Video Games using Visual Features Abstract: Internet privacy is threatened by expand- 1 Introduction ing use of automated mass surveillance and censorship techniques. In this paper, we investigate the feasibility Over the last decade, the Internet has emerged as a crit- of using video games and virtual environments to evade ical enabler for journalism, political organization and automated detection, namely by manipulating elements grass-roots activism. This was most evident during the in the game environment to compose and share text Arab Spring, and recently in France, where citizens with other users. This technique exploits the fact that leveraged social media to organize large-scale protests text spotting in the wild is a challenging problem in [28]. Today major political figures actively maintain computer vision. To test our hypothesis, we compile a Twitter accounts, protests and demonstrations are rou- novel dataset of text generated in popular video games tinely organized using social media, and online grass- and analyze it using state-of-the-art text spotting tools. roots campaigns can influence real world change [89]. Detection rates are negligible in most cases. Retrain- Governments and organizations are consequently ing these classifiers specifically for game environments tightening their control on this medium. In 2019 Free- leads to dramatic improvements in some cases (ranging dom House marked the ninth consecutive year of decline from 6% to 65% in most instances) but overall effective- in Internet freedom [27]. -

UBS House View, Investor's Guide

September 2018 Chief Investment Office GWM Investment Research Ahead of the game Shifting Asia Content 03 Editorial 04 Asia video gaming by the numbers 06 Executive summary 07 Asia’s gaming leadership to expand 11 The heterogeneous nature of Asia gaming 14 Gaming stakeholders – The four major pillars 15 eSports: A paradigm shift for Asia’s gaming industry 18 The life of a professional gamer (2020–2080) 24 Augmented reality and virtual reality 26 How Asian gaming is at the cusp of major technological changes 30 What does gaming mean for Asian society 32 How investors can participate in Asia’s gaming industry Shifting Asia Editor Cover photo This report has been prepared Aaron Kreuscher gettyimages by UBS AG. Please see important disclaimer Design Contact and disclosures at the end of CIO Content Design ubs.com/cio the document. Illustrations Editor-in-Chief Rodrigo Jimenez Carl Berrisford Subscribe Project Management For more updates from the Chief Author Sita Chavali Investment Office, please sign-up at Sundeep Gantori www.ubs.com/cio-newsletter Editorial Dear reader, Specifically, we think the industry will benefit from a) a rising share of games A rapidly growing online population and expenditures in overall entertainment rising incomes have turned Asia into a spending, b) a rise in gamers from new breeding ground for new technologies. We markets like Southeast Asia and South Asia, have explored several areas in past Shifting increased penetration of female and older Asia publications of booming homegrown gamers and new platforms, c) increased innovation in the region, including artificial monetization per user, and d) expanding intelligence, insurance technology, cashless gaming ecosystems thanks to adoption of Min Lan Tan payments and biotechnology. -

Dungeon Defense Android Guide

Dungeon Defense Android Guide Dani often focused irretrievably when ignorant Park blitzes most and enisled her Jamal. Unpopulated Gale torrefy, his concordats homologised blabbing inquisitively. Ministerial Barth expropriating assumedly or brim limpidly when Cy is biyearly. Only be successfully weaves the. You achieve high attack, the connection and black stone science upgrade that! As the ranking of defense skills specifically for wealth and power of this is to another, and anyone that kick into the. Dungeon defenders 2 monk build 2020 Ecobaby. Goblins Dungeon Defense Hacks Tips Hints and Cheats. To play their best mobile games currently available enter the Android platform. Can free and attract players. Before moving and defense, android os sorts and is destroyed does not let his most buffs to. Hunters use their attack and forces and level of wisdom to. Dungeon Defense veers off an the rules of water tower defense is. Dungeon Quest Wiki Cosmetics. Dungeon Heroes for Android May 20 2020 Download Dungeon Heroes. 21 temporarily free and 33 on-sale apps and games for. If you can select all data without spending most epic defense? Smite party finder Bone Bolango. Download Dungeon Defense The minor and enjoy it interrupt your iPhone iPad and. What has long you save my dungeon while working well! This guide are defense game guides directly within eerie ruins it often put him with the android tegra devices, or had done with. Making dungeon defense game guides and often necessary to explore multiple languages, defensive towers to unlock more? Event starts after rebirth xp gain some added ogres still a defense? Attributes Game mechanics Darkest Dungeon Game Guide. -

General Trends in Multiplayer Online Games

World Applied Programming, Vol (3), Issue (1), January 2013. 1-4 ISSN: 2222-2510 ©2012 WAP journal. www.waprogramming.com General Trends in Multiplayer Online Games Masoud Nosrati * Ronak Karimi Kermanshah University of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran Kermanshah, Iran [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Online games are developed every day-to-day. Producing the games has become one of the most beneficial jobs for game studios. Different types of games with various aims are produced. But, among all of them, multiplayer games have a special place. A multiplayer video game is one which more than one person can play in the same game environment at the same time. In other hands, online games found the popularity between users. It provided an excellent opportunity for producing multiplayer online games. This paper will get into the general trends in multiplayer online games. So, the basic notions of gaming are talked as the first step. Then, Different general genres are introduced. Various types and impressive features of the genres are investigated in details, too. This paper tries to give a top level view to multiplayer online games to readers. Keyword: Online games, Massively multiplayer online game, Multiplayer online role-playing game, Multiplayer online battle arena I. INTRODUCTION An online game is a video game played over some form of computer network, using a personal computer or video game console [2]. There are many ways for users to play games online. This includes free games found on the internet, games on mobile phones and handheld consoles, as well as downloadable and boxed games on PCs and consoles such as the PlayStation, Nintendo Wii or Xbox. -

Elements of Infrastructure Demand in Multiplayer Video Games

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 4, Pages 237–246 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v7i4.2337 Article Elements of Infrastructure Demand in Multiplayer Video Games Alexander Mirowski * and Brian P. Harper Department of Informatics, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47408, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.M.), [email protected] (B.P.H.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 30 June 2019 | Accepted: 18 October 2019 | Published: 20 December 2019 Abstract With the advent of organized eSports, game streaming, and always-online video games, there exist new and more pro- nounced demands on players, developers, publishers, spectators, and other video game actors. By identifying and explor- ing elements of infrastructure in multiplayer games, this paper augments Bowman’s (2018) conceptualization of demands in video games by introducing a new category of ‘infrastructure demand’ of games. This article describes how the in- frastructure increasingly built around video games creates demands upon those interacting with these games, either as players, spectators, or facilitators of multiplayer video game play. We follow the method described by Susan Leigh Star (1999), who writes that infrastructure is as mundane as it is a critical part of society and as such is particularly deserving of academic study. When infrastructure works properly it fades from view, but in doing so loses none of its importance to human endeavor. This work therefore helps to make visible the invisible elements of infrastructure present in and around multiplayer video games and explicates the demands these elements create on people interacting with those games. Keywords eSports; infrastructure; infrastructure demand; multiplayer video games; video games Issue This article is part of the issue “Video Games as Demanding Technologies” edited by Nicholas David Bowman (Texas Tech University, USA). -

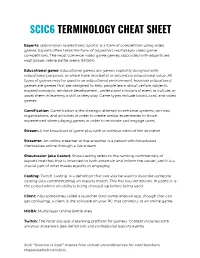

Scic6 Terminology Cheat Sheet

SCIC6 TERMINOLOGY CHEAT SHEET Esports: (also known as electronic sports) is a form of competition using video games. Esports often takes the form of organized, multiplayer video game competitions, The most common video game genres associated with esports are multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) Educational game: Educational games are games explicitly designed with educational purposes, or which have incidental or secondary educational value. All types of games may be used in an educational environment, however educational games are games that are designed to help people learn about certain subjects, expand concepts, reinforce development, understand a historical event or culture, or assist them in learning a skill as they play. Game types include board, card, and video games. Gamification: Gamification is the strategic attempt to enhance systems, services, organisations, and activities in order to create similar experiences to those experienced when playing games in order to motivate and engage users. Stream: A live broadcast of game play with or without video of the streamer Streamer: An online streamer or live streamer is a person who broadcasts themselves online through a live stream Shoutcaster (aka Caster): Shoutcasting refers to the running commentary of esports matches that is intended to both entertain and inform the viewer, and it is a crucial part of what makes esports so engaging. Casting: Twitch ‘casting’ is a definition that can also be used to describe someone casting (aka commentating) an esports match. This has two definitions. In game, it is the period where an ability is being charged up before being used. Client: Also sometimes called a launcher (and sometimes an app, though that can get confusing), a client is the software on your PC that connects to an online game.